·The Performance Group in India February-April 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

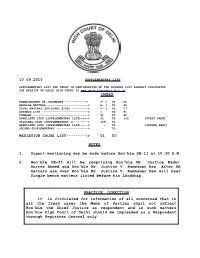

10.09.2015 Mediation Cause List

10.09.2015 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in' INDEX PRONOUNCEMNT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J- 1 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> R- 1 TO 65 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F- 1 TO 17 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 91 COMPANY -------------------------------> 92 TO 92 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 93 TO 108 (FIRST PART) ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 109 TO APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> - TO (SECOND PART) SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> - TO MEDIATION CAUSE LIST---------> 01 TO NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. 2. Hon'ble DB-II will be comprising Hon'ble Mr. Justice Badar Durrez Ahmed and Hon'ble Mr. Justice V. Kameswar Rao. After DB matters are over Hon'ble Mr. Justice V. Kameswar Rao will hear Single bench matters listed before his Lordship. PRACTICE DIRECTION It is circulated for information of all concerned that in all the fresh cases the Memo of Parties shall not reflect Hon'ble the Chief Justice as respondent and in such matters Hon'ble High Court of Delhi should be impleaded as a Respondent through Registrar General only. C I R C U L A R It is hereby circulated for information of all concerned that a separate nomenclature "SERTA" has been created in this Court for Service Tax Appeals filed under the relevant Sections of the Finance Act, 1994 read with the Central Excise Act, 1944 and a new filing code "1309" has been assigned to such appeals. -

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

• India Has Pledged $1.25 Million to the UN Relief Agency for Palestinian

India has pledged $1.25 million to the UN relief agency for Palestinian refugees as it voiced concern over the fragile situation and ongoing conflicts in the middle-east region. Singapore has the highest achieving students in international education rankings, with its teenagers coming top in tests in maths, reading and science. India was formally designated as a ‘Major Defence Partner’ of the United States. The 2016 World Power Language Index (PLI) announced that English language is the most powerful language in the world. The index was published by World Economic Forum (WEF). Hindi language was ranked 10th in the 2016 PLI. Pakistan has lifted an "undeclared" ban on import of ginned cotton from India, days after rejecting a consignment of 10,000 bales of cotton from India citing violation of plant quarantine rules by importers. In an effort to enhance cooperation in education between the two countries, India will establish a center of excellence in information technology at Egypt's oldest and most prestigious Al- Azhar University. Dr. António Costa, Prime Minister of the Republic of Portugal will be the Chief Guest at the 14th Pravasi Bharatiya Divas Convention to be held from 7 to 9 January, 2017 at Bengaluru in Karnataka. Mr. Michael Ashwin Satyandre Adhin, Vice President of the Republic of Suriname will be the Special Guest at the Youth Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (PBD) to be held on 7 January 2017 in Bengaluru. Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur is India’s highest-ranked institution features in the Top 100 QS Graduate Employability Rankings 2016-17. Turkey will chair the Energy Club of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 2017, becoming the first non-SCO country to hold its term presidency. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Badal Sircar

Badal Sircar Scripting a Movement Shayoni Mitra The ultimate answer [...] is not for a city group to prepare plays for and about the working people. The working people—the factory workers, the peasants, the landless laborers—will have to make and perform their own plays. [...] This process of course, can become widespread only when the socio-economic movement for emancipation of the working class has also spread widely. When that happens the Third Theatre (in the context I have used it) will no longer have a separate function, but will merge with a transformed First Theatre. —Badal Sircar, 23 November 1981 (1982:58) It is impossible to discuss the history of modern Indian theatre and not en- counter the name of Badal Sircar. Yet one seldom hears his current work talked of in the present. How is it that one of the greatest names, associated with an exemplary body of dramatic work, gets so easily lost in a haze of present-day ignorance? While much of his previous work is reverentially can- onized, his present contributions are less well known and seldom acknowl- edged. It was this slippage I set out to examine. I expected to find an ailing man reminiscing of past glories. I was warned that I might find a cynical per- son, an incorrigible skeptic weary of the world. Instead, I encountered an in- domitable spirit walking along his life path looking resolutely ahead. A kind old man who drew me a map to his house and saved tea for me in a thermos. A theatre person extraordinaire recounting his latest workshop in Laos, devis- ing how to return as soon as possible. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Andha Yug: the Age of Darkness by Dharamvir Bharati (Review)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) [Review of: A. Bhalla (2010) Dharamvir Bharati. Andha yug: the age of darkness] Bala, S. DOI 10.1353/atj.2014.0010 Publication date 2014 Document Version Final published version Published in Asian Theatre Journal Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bala, S. (2014). [Review of: A. Bhalla (2010) Dharamvir Bharati. Andha yug: the age of darkness]. Asian Theatre Journal, 31(1), 334-336. https://doi.org/10.1353/atj.2014.0010 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Andha Yug: The Age of Darkness by Dharamvir Bharati (review) Sruti Bala Asian Theatre Journal, Volume 31, Number 1, Spring 2014, pp. 334-336 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: 10.1353/atj.2014.0010 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/atj/summary/v031/31.1.bala.html Access provided by Amsterdam Universiteit (22 Apr 2014 08:11 GMT) 334 Book Reviews directly engaging in the existing scholarly debate over whether or not the two plays embrace feminist causes or ultimately adhere to the patriarchy. -

Girish Karnad 1 Girish Karnad

Girish Karnad 1 Girish Karnad Girish Karnad Born Girish Raghunath Karnad 19 May 1938 Matheran, British India (present-day Maharashtra, India) Occupation Playwright, film director, film actor, poet Nationality Indian Alma mater University of Oxford Genres Fiction Literary movement Navya Notable work(s) Tughalak 1964 Taledanda Girish Raghunath Karnad (born 19 May 1938) is a contemporary writer, playwright, screenwriter, actor and movie director in Kannada language. His rise as a playwright in 1960s, marked the coming of age of Modern Indian playwriting in Kannada, just as Badal Sarkar did in Bengali, Vijay Tendulkar in Marathi, and Mohan Rakesh in Hindi.[1] He is a recipient[2] of the 1998 Jnanpith Award, the highest literary honour conferred in India. For four decades Karnad has been composing plays, often using history and mythology to tackle contemporary issues. He has translated his plays into English and has received acclaim.[3] His plays have been translated into some Indian languages and directed by directors like Ebrahim Alkazi, B. V. Karanth, Alyque Padamsee, Prasanna, Arvind Gaur, Satyadev Dubey, Vijaya Mehta, Shyamanand Jalan and Amal Allana.[3] He is active in the world of Indian cinema working as an actor, director, and screenwriter, in Hindi and Kannada flicks, earning awards along the way. He was conferred Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan by the Government of India and won four Filmfare Awards where three are Filmfare Award for Best Director - Kannada and one Filmfare Best Screenplay Award. Early life and education Girish Karnad was born in Matheran, Maharashtra. His initial schooling was in Marathi. In Sirsi, Karnataka, he was exposed to travelling theatre groups, Natak Mandalis as his parents were deeply interested in their plays.[4] As a youngster, Karnad was an ardent admirer of Yakshagana and the theater in his village.[] He earned his Bachelors of Arts degree in Mathematics and Statistics, from Karnatak Arts College, Dharwad (Karnataka University), in 1958. -

Annual Report 1990 .. 91

SANGEET NAT~AKADEMI . ANNUAL REPORT 1990 ..91 Emblem; Akademi A wards 1990. Contents Appendices INTRODUCTION 0 2 Appendix I : MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION (EXCERPTS) 0 53 ORGANIZATIONAL SET-UP 05 AKADEMI FELLOWSHIPS/ AWARDS Appendix II : CALENDAR OF 19900 6 EVENTS 0 54 Appendix III : GENERAL COUNCIL, FESTIVALS 0 10 EXECUTIVE BOARD, AND THE ASSISTANCE TO YOUNG THEATRE COMMITTEES OF THE WORKERS 0 28 AKADEMID 55 PROMOTION AND PRESERVATION Appendix IV: NEW AUDIO/ VIDEO OF RARE FORMS OF TRADITIONAL RECORDINGS 0 57 PERFORMING ARTS 0 32 Appendix V : BOOKS IN PRINT 0 63 CULTURAL EXCHANGE Appendix VI : GRANTS TO PROGRAMMES 0 33 INSTITUTIONS 1990-91 064 PUBLICATIONS 0 37 Appendix VII: DISCRETIONARY DOCUMENTATION / GRANTS 1990-91 071 DISSEMINATION 0 38 Appendix VIll : CONSOLIDATED MUSEUM OF MUSICAL BALANCE SHEET 1990-91 0 72 INSTRUMENTS 0 39 Appendix IX : CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE TO SCHEDULE OF FIXED CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS 0 41 ASSETS 1990-91 0 74 LIBRARY AND LISTENING Appendix X : PROVIDENT FUND ROOMD41 BALANCE SHEET 1990-91 078 BUDGET AND ACCOUNTS 0 41 Appendix Xl : CONSOLIDATED INCOME & EXPENDITURE IN MEMORIAM 0 42 ACCOUNT 1990-91 KA THAK KENDRA: DELHI 0 44 (NON-PLAN & PLAN) 0 80 JA WAHARLAL NEHRU MANIPUR Appendix XII : CONSOLIDATED DANCE ACADEMY: IMPHAL 0 50 INCOME & EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN) 0 86 Appendix Xlll : CONSOLIDATED INCOME & EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT 1990-91 (PLAN) 0 88 Appendix XIV : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN & PLAN) 0 94 Appendix XV : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN) 0 104 Appendix XVI : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (PLAN) 0 110 Introduction Apart from the ongoing schemes and programmes, the Sangeet Natak Akademi-the period was marked by two major National Academy of Music, international festivals presented Dance, and Drama-was founded by the Akademi in association in 1953 for the furtherance of with the Indian Council for the performing arts of India, a Cultural Relations. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH TUESDAY, THE 08 SEPTEMBER, 2015 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 49 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 50 TO 54 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 55 TO 68 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 69 TO 86 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 08.09.2015 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 08.09.2015 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE JAYANT NATH FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. LPA 589/2015 HIMALAYAN INSTITUTE OF SANJEEV AGARWAL,MONIKA MEDICAL SCIENCES ARORA,T. SINGHDEV Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ANR 2. LPA 601/2015 SHAM LAAT PATTI RAYAL PRAVEEN AGRAWAL AND MANISH CM APPL. 18478/2015 SANGHARSH SAMITI GANDAHI CM APPL. 18479/2015 Vs. DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION CM APPL. 18480/2015 FOR ADMISSION _______________ 3. W.P.(CRL) 585/2015 KARAN BAHADUR SHAHA AJAY VERMA (DHCLSC),SANJEEV Vs. STATE BHANDARI Other Case filed against same P.S.-FIR No. :(WELCOME COLONY-99/1999) CRL.A. 187/2004 filed by KARAN BAHADUR SHAHA (Disposed on : 13-MAR-07 ) CRL.A. 474/2003 filed by YHANU SHAHA (Disposed on : 13-MAR-07 ) W.P.(CRL) 218/2010 filed by KARAN BAHADUR (Disposed on : 11-MAR-10 ) W.P.(CRL) 1180/2012 filed by KARAN BAHADUR SHAHA (Disposed on : 09-MAY-13 ) P.S.-FIR No. :(WELCOME COLONY-99/1999) AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 4. LPA 168/2015 UNION OF INDIA THR THE JASMEET SINGH,PRANAV SACHDEVA CM APPL. -

CRITICAL STUDY of INNOVATIONS and EXPERIMENTS in the PLAYS of GIRISH KARNAD Anita * Parul Mishra** ABSTRACT

IJRESS Volume 4, Issue 2 (February 2014) (ISSN 2249-7382) CRITICAL STUDY OF INNOVATIONS AND EXPERIMENTS IN THE PLAYS OF GIRISH KARNAD Anita * Parul Mishra** ABSTRACT Acting in its rudimentary forms as scolding, persuading, mocking or irritating somebody must have begun with the very birth of human beings on earth but theatre in its mature form is certainly an offshoot of an organized effort of some temperamentally sensitive social activists. It is now psychologically and linguistically proved fact that imitation is an inherent instinct present in all human beings. Objective of the present paper is to explore the experimentation and innovation in the plays of Girish Karnad for the survival of Indian theatrical traditions. Keywords: Tradition, Acting, Theatre, Folk elements, Imitation *Research Scholar,Department of English,Singhania University, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan International Journal of Research in Economics & Social Sciences http://www.euroasiapub.org 87 IJRESS Volume 4, Issue 2 (February 2014) (ISSN 2249-7382) **Assistant Professor, Deptt of Applied Sciences& Humanities,Dronacharya College Of Engineering, Gurgaon-123506, India International Journal of Research in Economics & Social Sciences http://www.euroasiapub.org 88 IJRESS Volume 4, Issue 2 (February 2014) (ISSN 2249-7382) 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Drama is a genre, an audiovisual medium for the expression of human sentiments. It is a mimetic representation of life. It is a blending of poetry, dancing and music. Drama is “literature that walks and talks before our eyes.”[1] In novel and epic, the writer narrates the story and reports the action in detail. But in the drama, the dramatist imitates the activities by action and speech.