MITOCW | MIT9 14S09 Lec36-Mp3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Resolution Cortical Imaging

High-Resolution Cortical Imaging Alex de Crespigny Ph.D., Ellen Grant M.D., Larry Wald Ph.D., Jean Augustinack Ph.D., Bruce Fischl Ph.D., Helen D’Arceuil Ph.D. Martinos Center, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA Structure of the cortex The adult cerebral cortex is a complex convoluted multilayered structure averaging around 2.3mm thick, but thinner (≤ 2mm) in the depths of the sulcal folds and thicker (3-4mm) at the crown of the gyri. It is typically divided into 6 layers depending upon the constituent cell types. On examination a section of the cortex, it is seen to consist of alternating white and gray layers from the surface inward: (1) a thin layer of white substance; (2) a layer of gray substance; (3) a second white layer (outer band of Baillarger or band of Gennari); (4) a second gray layer; (5) a third white layer (inner band of Baillarger); (6) a third gray layer, which rests on the medullary substance of the gyrus (1). Cortical neurons form a highly organized laminar and radial structure with extensive efferents. Long association fibers connect to distant regions of the ipsilateral hemisphere, while short fibers connect to nearby ipsilateral regions. Commissural fibers connect to the cortical regions of the contralateral hemisphere, and projection fibers reach from the cortex into the subcortical structures e.g., corticothalamic/subthalamic projections, etc. High resolution structural MRI of the cortex Conventional diagnostic clinical MRI scans, with in plane resolution of ~1mm and slice thickness up to 5mm can define the gray-white interface of the cerebral cortex but cannot visualize structure within the cortex itself. -

15 Telencephalon: Neocortex

15 Telencephalon: Neocortex Introduction.........................491 – Dendritic Clusters, Axonal Bundles and Radial Cell Cords As (Possible) Sulcal Pattern ........................498 Constituents of Neocortical Minicolumns . 582 Structural and Functional Subdivision – Microcircuitry of Neocortical Columns .... 586 ofNeocortex.........................498 – Neocortical Columns and Modules: – Structural Subdivision 1: Cytoarchitecture . 498 A Critical Commentary ............... 586 – Structural Subdivision 2: Myeloarchitecture . 506 Comparative Aspects ................... 591 – Structural Subdivision 3: Myelogenesis ....510 Synopsis of Main Neocortical Regions ...... 592 – Structural Subdivision 4: Connectivity .....510 – Introduction....................... 592 – Functional Subdivision ................516 – Association and Commissural Connections . 592 – Structural and Functional Subdivision: – Functional and Structural Asymmetry Overview .........................528 of the Two Hemispheres .............. 599 – Structural and Functional Localization – Occipital Lobe ..................... 600 in the Neocortex: Current Research – Parietal Lobe ...................... 605 and Perspectives ....................530 – TemporalLobe..................... 611 Neocortical Afferents ...................536 – Limbic Lobe and Paralimbic Belt ........ 617 Neocortical Neurons – FrontalLobe ...................... 620 and Their Synaptic Relationships ..........544 – Insula........................... 649 – IntroductoryNote...................544 – Typical Pyramidal -

Target-Specific Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Microscopy

NeuroImage 46 (2009) 382–393 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect NeuroImage journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ynimg Target-specific contrast agents for magnetic resonance microscopy Megan L. Blackwell a,b,⁎, Christian T. Farrar a,d, Bruce Fischl a,c,d, Bruce R. Rosen a,d a Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA b Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA c Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA d Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, USA article info abstract Article history: High-resolution ex vivo magnetic resonance (MR) imaging can be used to delineate prominent architectonic Received 2 July 2007 features in the human brain, but increased contrast is required to visualize more subtle distinctions. To aid Revised 5 December 2008 MR sensitivity to cell density and myelination, we have begun the development of target-specific Accepted 15 January 2009 paramagnetic contrast agents. This work details the first application of luxol fast blue (LFB), an optical Available online 30 January 2009 stain for myelin, as a white matter-selective MR contrast agent for human ex vivo brain tissue. Formalin-fixed human visual cortex was imaged with an isotropic resolution between 80 and 150 μm at 4.7 and 14 T before and after en bloc staining with LFB. Longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates in LFB-stained tissue increased proportionally with myelination at both field strengths. Changes in R1 resulted in larger contrast-to-noise ratios (CNR), per unit time, on T1-weighted images between more myelinated cortical layers (IV–VI) and adjacent, superficial layers (I–III) at both field strengths. -

Direct Visualization of the Perforant Pathway in the Human Brain with Ex Vivo Diffusion Tensor Imaging

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 28 May 2010 HUMAN NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00042 Direct visualization of the perforant pathway in the human brain with ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging Jean C. Augustinack1*, Karl Helmer1, Kristen E. Huber1, Sita Kakunoori1, Lilla Zöllei1,2 and Bruce Fischl1,2 1 Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, USA 2 Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA Edited by: Ex vivo magnetic resonance imaging yields high resolution images that reveal detailed cerebral Andreas Jeromin, Banyan Biomarkers, anatomy and explicit cytoarchitecture in the cerebral cortex, subcortical structures, and white USA matter in the human brain. Our data illustrate neuroanatomical correlates of limbic circuitry with Reviewed by: Konstantinos Arfanakis, Illinois Institute high resolution images at high field. In this report, we have studied ex vivo medial temporal of Technology, USA lobe samples in high resolution structural MRI and high resolution diffusion MRI. Structural and James Gee, University of Pennsylvania, diffusion MRIs were registered to each other and to histological sections stained for myelin for USA validation of the perforant pathway. We demonstrate probability maps and fiber tracking from Christopher Kroenke, Oregon Health and Science University, USA diffusion tensor data that allows the direct visualization of the perforant pathway. Although it *Correspondence: is not possible to validate the DTI data with invasive measures, results described here provide Jean Augustinack, Athinoula A. an additional line of evidence of the perforant pathway trajectory in the human brain and that Martinos Center for Biomedical the perforant pathway may cross the hippocampal sulcus. -

Staging of Alzheimer Disease-Associated Neurowbrillary Pathology Using Parayn Sections and Immunocytochemistry

Acta Neuropathol (2006) 112:389–404 DOI 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z METHODS REPORT Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neuroWbrillary pathology using paraYn sections and immunocytochemistry Heiko Braak · Irina AlafuzoV · Thomas Arzberger · Hans Kretzschmar · Kelly Del Tredici Received: 8 June 2006 / Revised: 21 July 2006 / Accepted: 21 July 2006 / Published online: 12 August 2006 © Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Assessment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)- revised here by adapting tissue selection and process- related neuroWbrillary pathology requires a procedure ing to the needs of paraYn-embedded sections (5–15 m) that permits a suYcient diVerentiation between initial, and by introducing a robust immunoreaction (AT8) for intermediate, and late stages. The gradual deposition hyperphosphorylated tau protein that can be processed of a hyperphosphorylated tau protein within select on an automated basis. It is anticipated that this neuronal types in speciWc nuclei or areas is central to revised methodological protocol will enable a more the disease process. The staging of AD-related neuroW- uniform application of the staging procedure. brillary pathology originally described in 1991 was per- formed on unconventionally thick sections (100 m) Keywords Alzheimer’s disease · NeuroWbrillary using a modern silver technique and reXected the pro- changes · Immunocytochemistry · gress of the disease process based chieXy on the topo- Hyperphosphorylated tau protein · Neuropathologic graphic expansion of the lesions. To better meet the staging · Pretangles demands of routine laboratories this procedure is Introduction This study was made possible by funding from the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and BrainNet Europe II (European Commission LSHM-CT-2004- The development of intraneuronal lesions at selec- 503039). -

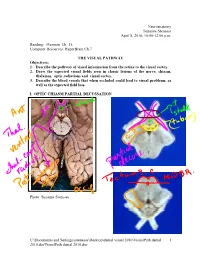

Visualpath Dental 2010.Jnt

Neuroanatomy Suzanne Stensaas April 8, 2010, 10:00-12:00 p.m. Reading: Waxman Ch. 15, Computer Resources: HyperBrain Ch 7 THE VISUAL PATHWAY Objectives: 1. Describe the pathway of visual information from the retina to the visual cortex. 2. Draw the expected visual fields seen in classic lesions of the nerve, chiasm, thalamus, optic radiations and visual cortex. 3. Describe the blood vessels that when occluded could lead to visual problems, as well as the expected field loss. I. OPTIC CHIASM PARTIAL DECUSSATION Photo: Suzanne Stensaas C:\Documents and Settings\sstensaas\Desktop\dental visual 2010\VisualPath dental 1 2010.docVisualPath dental 2010.doc II. OPTIC TRACT Ganglion cell axons diverge A. 90% go to Lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of thalamus (the retino- geniculo-calcarine path ) B. 10% go to Superior colliculus and pretectum (the retinocollicular path for reflexes) C. The hypothalamus for circadian rhythms (not to be discussed) III. THALAMIC RELAY NUCLEUS -- the LATERAL GENICULATE NUCLEUS OR BODY A. Specific retinotopic projection. B. Six layers. Three layers get input from from each eye. Thalamus Red LGN LGN Nucleus C:\Documents and Settings\sstensaas\Desktop\dental visual 2010\VisualPath dental 2 2010.docVisualPath dental 2010.doc The optic tract projects to the LGN Crainial Nerves, Wilson-Pauwels et al., 1988 IV. OPTIC RADIATIONS A. Retinotopic organization from the LGN neurons to the cortex. B. Axons of neurons in the lateral geniculate form the optic radiations = geniculocalcarine tract. The retinotopic organization is maintained. 1. Some loop forward over inferior (or temporal) horn of lateral ventricle = Meyer's Loop 2. Other axons take a more direct posterior course through the deep parietal white matter. -

Staging of Alzheimer Disease-Associated Neurowbrillary Pathology Using Parayn Sections and Immunocytochemistry

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Acta Neuropathol (2006) 112:389–404 DOI 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z METHODS REPORT Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neuroWbrillary pathology using paraYn sections and immunocytochemistry Heiko Braak · Irina AlafuzoV · Thomas Arzberger · Hans Kretzschmar · Kelly Del Tredici Received: 8 June 2006 / Revised: 21 July 2006 / Accepted: 21 July 2006 / Published online: 12 August 2006 © Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Assessment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)- revised here by adapting tissue selection and process- related neuroWbrillary pathology requires a procedure ing to the needs of paraYn-embedded sections (5–15 m) that permits a suYcient diVerentiation between initial, and by introducing a robust immunoreaction (AT8) for intermediate, and late stages. The gradual deposition hyperphosphorylated tau protein that can be processed of a hyperphosphorylated tau protein within select on an automated basis. It is anticipated that this neuronal types in speciWc nuclei or areas is central to revised methodological protocol will enable a more the disease process. The staging of AD-related neuroW- uniform application of the staging procedure. brillary pathology originally described in 1991 was per- formed on unconventionally thick sections (100 m) Keywords Alzheimer’s disease · NeuroWbrillary using a modern silver technique and reXected the pro- changes · Immunocytochemistry · gress of the disease process based chieXy on the topo- Hyperphosphorylated tau protein · Neuropathologic graphic expansion of the lesions. To better meet the staging · Pretangles demands of routine laboratories this procedure is Introduction This study was made possible by funding from the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and BrainNet Europe II (European Commission LSHM-CT-2004- The development of intraneuronal lesions at selec- 503039). -

Primate Visual Cortex PASKO RAKIC*, IVAN SURER, and ROBERT W

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 88, pp. 2083-2087, March 1991 Neurobiology A novel cytoarchitectonic area induced experimentally within the primate visual cortex PASKO RAKIC*, IVAN SURER, AND ROBERT W. WILLIAMSt Section of Neuroanatomy, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06510 Contributed by Pasko Rakic, December 14, 1990 ABSTRACT The cerebral cortex is divisible into a number oretically, such a partial transformation could be induced if ofcytoarchitectonic areas, but developmental mechanisms that neurons normally destined to become part ofarea 17 received regulate their number and size remain unknown. Here we afferent connections appropriate for other cortical areas. provide evidence that reducing the population of selected According to this hypothesis, cortical neurons must possess thalamic fibers projecting into the primary visual cortex (area some intrinsic properties that can be modified during devel- 17) of monkeys during midgestation induces the formation of a opment, but only to a limited degree. Here we provide direct novel cytoarchitectonic area situated along the border of and evidence that prenatal manipulation of geniculocortical ax- embedded within area 17. This region, termed area X, differs ons can result in the transformation of parts of area 17 into cytoarchitectonically from both area 17 and the adjacent cortical regions with cytological characteristics that are sim- secondary visual cortex (area 18). We propose that an aberrant ilar to, yet clearly distinguishable from, both area 17 and the combination of thalamic and cortical connections acting on a adjacent secondary visual cortex, area 18. This experimen- portion of prospective area 17 deprived of its normal thalamic tally induced, cytoarchitectonically unique cortical area, input may result in formation of a hybrid cortex. -

Morphological Alterations of the Pyramidal and Stellate Cells of the Visual Cortex in Schizophrenia

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 22: 669, 2021 Morphological alterations of the pyramidal and stellate cells of the visual cortex in schizophrenia IOANNIS MAVROUDIS1‑3, FOIVOS PETRIDES1,4, DIMITRIOS KAZIS4, SYMELA CHATZIKONSTANTINOU4, ELENI KARANTALI4, ALIN CIOBICA5‑7, ALIN‑CONSTANTIN IORDACHE8, ROMEO DOBRIN8, CONSTANTIN TRUS9, SAMUEL NJAU10, VASILIKI COSTA1,3 and STAVROS BALOYANNIS1,3 1Laboratory of Neuropathology and Electron Microscopy First Department of Neurology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki 54634, Greece; 2Department of Neurology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds LS1 3EX, UK; 3Institute For Research Of Alzheimer's Disease, Other Neurodegenerative Diseases And Normal Aging, Heraklion Langada 57200; 4Third Department of Neurology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece; 5Department of Biology, Faculty of Biology, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iasi 700506; 6Academy of Romanian Scientists, Bucuresti 050094; 7Center of Biomedical Research, Romanian Academy, Iasi 700506; 8Faculty of Medicine, ‘Grigore T. Popa’, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115; 9Department of Morphological and Functional Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Dunarea de Jos University, Galati 050094, Romania; 10Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki 54634, Greece Received January 24, 2021; Accepted March 19, 2021 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.10101 Abstract. Schizophrenia is a severe brain disorder character‑ aspiny interneurons. The present results may explain -

CURRENT STATUS of REHABILITATION for PATIENTS with HOMONYMOUS FIELD DEFECTS Susanne Trauzettel-Klosinski MD Center for Ophthalmology, University of Tuebingen Germany

CURRENT STATUS OF REHABILITATION FOR PATIENTS WITH HOMONYMOUS FIELD DEFECTS Susanne Trauzettel-Klosinski MD Center for Ophthalmology, University of Tuebingen Germany LEARNING OBJECTIVES INTRODUCTION 1) The att endee will be able to describe the disabiliti es In pati ents with brain damage, oft en the hemianopic and handicaps in everyday life caused by hemianopia. fi eld defect is not diagnosed, because other neurological symptoms, such as hemiplegia, are predominant. The 2) The att endee will be able to explain the features of the mean ti me between the brain damage and the diagnosis reading disorder and its rehabilitati on opti ons. of the hemianopia was found to be 3 +/- 2 months (Zhang 3) The att endee will be able to understand what et al 2006). Additi onally, the pati ents oft en do not realize rehabilitati on approach to improve orientati on is the fi eld defect, even though they experience acti vity appropriate. limitati ons in their everyday life. The classifi cati on of the World Health Organizati on (WHO 2004) for Functi oning, Disability and Health (ICF) includes CME QUESTIONS three main aspects, which have to be considered in visual 1) Which spontaneous adapti ve strategies are favorable impairment: 1) impairment – related to the organ, 2) to improve orientati on? disability or acti vity limitati on – related to the person and 3) handicap or parti cipati on restricti on – related to the a) turning the head to the blind side society. b) saccades towards the blind side Homonymous fi eld defects cause two main disabiliti es/ c) shift ing att enti on to the blind side acti vity limitati ons: 2) The hemianopic reading disorder is caused by 1. -

®Rifiin<Tl Articles Anb Clinical Cases

[JULY, 1912.] BEAIN PART I., VOL. 35. ®rifiin<tl Articles anb Clinical Cases. THE CYTO-AECHITECTUEE OF THE CEREBRAL CORTEX OF A HUMAN FCETUS OF EIGHTEEN WEEKS. BY JOSEPH SHAW BOLTON, M.D., D.Sc, F.R.O.P., AND • Downloaded from JOHN MURRAY MOYES, M.B., CH.B., D.P.M. PAGE I.—INTRODUCTION ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 II.—MATERIAL AND METHODS ... ... ... ... ... 3 by guest on January 7, 2015 III.—ANATOMICAL DESCRIPTION OP THE CEREBRUM ... ... ... 5 IV.—THE LOCALIZATION OF THE BETZ-CBLL AREA ... ... ... 8 V.—THE LOCALIZATION OF THE VISBO-SBNSOBY AREA... ... ... 10 VI.—THE CyTO-AKCHITECTURE OF— (1) The Precentral (Betz-oell) Cortex ... ... ... ... 12 (2) The Post-central Cortex ... ... ...• ... ... 15 (3) The Cortex of the Visuo-sensory Area ... ... ... 20 (4) The Cortex of the Gyrus Cinguli ... ... ... ... 21 (5) The Cortex of the Anterior Frontal Region... ... ... 22 VII.—SUMMARY ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 24 I.—INTRODUCTION. OP late years much progress has been made in the study of the cyto-architecture of the cortex cerebri and of cerebral function. In 1905 and 1907, Campbell [6] and Brodmann [4] respectively'published complete maps of the various areas into which the human adult cerebral cortex may be divided, and further details together with similar maps dealing with the cortex of certain orders of the mammalia have been published both by them and by other workers, notably by Mott [9], Mott and Kelley [10], Mott and Schuster [11 and 12], Watson [14]. As far as we are aware, however, no systematic study of the early evolution of the cyto-architecture of the human cortex cerebri has hitherto been attempted. -

Layer-Specific Variation of Iron Content in Cerebral Cortex As a Source Of

Layer-specific variation of iron content in cerebral cortex as a source of MRI contrast Masaki Fukunagaa,1, Tie-Qiang Lia, Peter van Gelderena, Jacco A. de Zwarta, Karin Shmuelia, Bing Yaoa, Jongho Leea, Dragan Maricb, Maria A. Aronovac, Guofeng Zhangc, Richard D. Leapmanc, John F. Schenckd, Hellmut Merklea, and Jeff H. Duyna aAdvanced MRI, Laboratory of Functional and Molecular Imaging, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; bLaboratory of Neurophysiology, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; cLaboratory of Bioengineering and Physical Science, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; and dGeneral Electric Global Research Center, Niskayuna, NY 12309 Edited* by Leslie G. Ungerleider, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved January 4, 2010 (received for review September 28, 2009) Recent advances in high-field MRI have dramatically improved the and is, together with the resonance frequency, particularly sen- visualization of human brain anatomy in vivo. Most notably, in sitive to spatial magnetic susceptibility variations. Most notably, cortical gray matter, strong contrast variations have been observed contrast based on resonance frequency shifts of tissue, derived that appear to reflect the local laminar architecture. This contrast from the phase of gradient-echo signals, has allowed the robust has been attributed to subtle variations in the magnetic properties visualization of laminar structure in a number of neocortical of brain tissue, possibly reflecting varying iron and myelin content. regions, including primary visual and motor cortices (17) (Fig. 1). To establish the origin of this contrast, MRI data from postmortem Despite this progress, the origin of cortical laminar contrast brain samples were compared with electron microscopy and observed with high-field MRI remains unclear.