Structural Changes That Occur During Normal Aging of Primate Cerebral Hemispheres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Factors for the Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Clin Geriatr Manuscript Author Med. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 April 24. Published in final edited form as: Clin Geriatr Med. 2013 November ; 29(4): 873–893. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.009. Risk Factors for the Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia Noll L. Campbell, PharmDa,b,c,d,*, Fred Unverzagt, PhDe, Michael A. LaMantia, MD, MPHb,c,f, Babar A. Khan, MD, MSb,c,f, and Malaz A. Boustani, MD, MPHb,c,f aDepartment of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA bIndiana University Center for Aging Research, Indianapolis, IN, USA cRegenstrief Institute, Inc, Indianapolis, IN, USA dDepartment of Pharmacy, Wishard Health Services, Indianapolis, IN, USA eDepartment of Psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA fDepartment of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA Keywords Mild cognitive impairment; Dementia; Risk factors; Genetics; Biomarkers Introduction As identified in previously published articles, including those published in this issue, the detection of early cognitive impairment among older adult populations is worthy of diagnostic and clinical recognition. Several definitions and classifications have been applied to this form of cognitive impairment over time1–4 including mild cognitive impairment (MCI),4–6 cognitive impairment no dementia,7,8 malignant senescent forgetfulness,9 and age-associated cognitive decline.10 -

High-Resolution Cortical Imaging

High-Resolution Cortical Imaging Alex de Crespigny Ph.D., Ellen Grant M.D., Larry Wald Ph.D., Jean Augustinack Ph.D., Bruce Fischl Ph.D., Helen D’Arceuil Ph.D. Martinos Center, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA Structure of the cortex The adult cerebral cortex is a complex convoluted multilayered structure averaging around 2.3mm thick, but thinner (≤ 2mm) in the depths of the sulcal folds and thicker (3-4mm) at the crown of the gyri. It is typically divided into 6 layers depending upon the constituent cell types. On examination a section of the cortex, it is seen to consist of alternating white and gray layers from the surface inward: (1) a thin layer of white substance; (2) a layer of gray substance; (3) a second white layer (outer band of Baillarger or band of Gennari); (4) a second gray layer; (5) a third white layer (inner band of Baillarger); (6) a third gray layer, which rests on the medullary substance of the gyrus (1). Cortical neurons form a highly organized laminar and radial structure with extensive efferents. Long association fibers connect to distant regions of the ipsilateral hemisphere, while short fibers connect to nearby ipsilateral regions. Commissural fibers connect to the cortical regions of the contralateral hemisphere, and projection fibers reach from the cortex into the subcortical structures e.g., corticothalamic/subthalamic projections, etc. High resolution structural MRI of the cortex Conventional diagnostic clinical MRI scans, with in plane resolution of ~1mm and slice thickness up to 5mm can define the gray-white interface of the cerebral cortex but cannot visualize structure within the cortex itself. -

Use of Neurotechnology in Normal Brain Aging and Alzheimer

Use of Neurotechnology in Normal Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and AD-Related Dementias (ADRD) NIA Virtual Workshop Division of Neuroscience April 27, 2020 Final June 1, 2020 This meeting summary was prepared by Dave Frankowski, Rose Li and Associates, Inc., under contract to the National Institute on Aging (NIA). The views expressed in this document reflect both individual and collective opinions of the focus group participants an d not necessarily those of NIA. Review of earlier versions of this meeting summary by the following individuals is gratefully acknowledged: Ali Abedi, Ed Boyden, Dana Carluccio, Monica Fabiani, Mariana Figueiro, Jay Gupta, Ben Hampstead, Marie Hayes, Abhishek Rege, Fiza Singh, Nancy Tuvesson, Shuai Xu. Neurotechnology in Normal Brain Aging, AD, and ADRD April 27, 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 Meeting Summary ................................................................................................................. 3 Welcome and Opening Remarks .............................................................................................................. 3 Using Non-invasive Sensory Stimulation to Ameliorate Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Symptoms 3 Flipping the Switch: How to Use Light to Improve the Lives and Health of Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias .............................................................................................................. -

15 Telencephalon: Neocortex

15 Telencephalon: Neocortex Introduction.........................491 – Dendritic Clusters, Axonal Bundles and Radial Cell Cords As (Possible) Sulcal Pattern ........................498 Constituents of Neocortical Minicolumns . 582 Structural and Functional Subdivision – Microcircuitry of Neocortical Columns .... 586 ofNeocortex.........................498 – Neocortical Columns and Modules: – Structural Subdivision 1: Cytoarchitecture . 498 A Critical Commentary ............... 586 – Structural Subdivision 2: Myeloarchitecture . 506 Comparative Aspects ................... 591 – Structural Subdivision 3: Myelogenesis ....510 Synopsis of Main Neocortical Regions ...... 592 – Structural Subdivision 4: Connectivity .....510 – Introduction....................... 592 – Functional Subdivision ................516 – Association and Commissural Connections . 592 – Structural and Functional Subdivision: – Functional and Structural Asymmetry Overview .........................528 of the Two Hemispheres .............. 599 – Structural and Functional Localization – Occipital Lobe ..................... 600 in the Neocortex: Current Research – Parietal Lobe ...................... 605 and Perspectives ....................530 – TemporalLobe..................... 611 Neocortical Afferents ...................536 – Limbic Lobe and Paralimbic Belt ........ 617 Neocortical Neurons – FrontalLobe ...................... 620 and Their Synaptic Relationships ..........544 – Insula........................... 649 – IntroductoryNote...................544 – Typical Pyramidal -

Mild Cognitive Impairment (Mci) and Dementia February 2017

CareCare Process Process Model Model FEBRUARY MONTH 2015 2017 DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Dementia minor update - 12 / 2020 The Intermountain Cognitive Care Development Team developed this care process model (CPM) to improve the diagnosis and treatment of patients with cognitive impairment across the staging continuum from mild impairment to advanced dementia. It is primarily intended as a tool to assist primary care teams in making the diagnosis of dementia and in providing optimal treatment and support to patients and their loved ones. This CPM is based on existing guidelines, where available, and expert opinion. WHAT’S INSIDE? Why Focus ON DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT ALGORITHMS OF DEMENTIA? Algorithm 1: Diagnosing Dementia and MCI . 6 • Prevalence, trend, and morbidity. In 2016, one in nine people age 65 and Algorithm 2: Dementia Treatment . .. 11 older (11%) has Alzheimer’s, the most common dementia. By 2050, that Algorithm 3: Driving Assessment . 13 number may nearly triple, and Utah is expected to experience one of the Algorithm 4: Managing Behavioral and greatest increases of any state in the nation.HER,WEU One in three seniors dies with Psychological Symptoms . 14 a diagnosis of some form of dementia.ALZ MCI AND DEMENTIA SCREENING • Costs and burdens of care. In 2016, total payments for healthcare, long-term AND DIAGNOSIS ...............2 care, and hospice were estimated to be $236 billion for people with Alzheimer’s MCI TREATMENT AND CARE ....... HUR and other dementias. Just under half of those costs were borne by Medicare. MANAGEMENT .................8 The emotional stress of dementia caregiving is rated as high or very high by nearly DEMENTIA TREATMENT AND PIN, ALZ 60% of caregivers, about 40% of whom suffer from depression. -

Target-Specific Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Microscopy

NeuroImage 46 (2009) 382–393 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect NeuroImage journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ynimg Target-specific contrast agents for magnetic resonance microscopy Megan L. Blackwell a,b,⁎, Christian T. Farrar a,d, Bruce Fischl a,c,d, Bruce R. Rosen a,d a Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA b Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA c Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA d Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, USA article info abstract Article history: High-resolution ex vivo magnetic resonance (MR) imaging can be used to delineate prominent architectonic Received 2 July 2007 features in the human brain, but increased contrast is required to visualize more subtle distinctions. To aid Revised 5 December 2008 MR sensitivity to cell density and myelination, we have begun the development of target-specific Accepted 15 January 2009 paramagnetic contrast agents. This work details the first application of luxol fast blue (LFB), an optical Available online 30 January 2009 stain for myelin, as a white matter-selective MR contrast agent for human ex vivo brain tissue. Formalin-fixed human visual cortex was imaged with an isotropic resolution between 80 and 150 μm at 4.7 and 14 T before and after en bloc staining with LFB. Longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates in LFB-stained tissue increased proportionally with myelination at both field strengths. Changes in R1 resulted in larger contrast-to-noise ratios (CNR), per unit time, on T1-weighted images between more myelinated cortical layers (IV–VI) and adjacent, superficial layers (I–III) at both field strengths. -

Direct Visualization of the Perforant Pathway in the Human Brain with Ex Vivo Diffusion Tensor Imaging

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 28 May 2010 HUMAN NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00042 Direct visualization of the perforant pathway in the human brain with ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging Jean C. Augustinack1*, Karl Helmer1, Kristen E. Huber1, Sita Kakunoori1, Lilla Zöllei1,2 and Bruce Fischl1,2 1 Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, USA 2 Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA Edited by: Ex vivo magnetic resonance imaging yields high resolution images that reveal detailed cerebral Andreas Jeromin, Banyan Biomarkers, anatomy and explicit cytoarchitecture in the cerebral cortex, subcortical structures, and white USA matter in the human brain. Our data illustrate neuroanatomical correlates of limbic circuitry with Reviewed by: Konstantinos Arfanakis, Illinois Institute high resolution images at high field. In this report, we have studied ex vivo medial temporal of Technology, USA lobe samples in high resolution structural MRI and high resolution diffusion MRI. Structural and James Gee, University of Pennsylvania, diffusion MRIs were registered to each other and to histological sections stained for myelin for USA validation of the perforant pathway. We demonstrate probability maps and fiber tracking from Christopher Kroenke, Oregon Health and Science University, USA diffusion tensor data that allows the direct visualization of the perforant pathway. Although it *Correspondence: is not possible to validate the DTI data with invasive measures, results described here provide Jean Augustinack, Athinoula A. an additional line of evidence of the perforant pathway trajectory in the human brain and that Martinos Center for Biomedical the perforant pathway may cross the hippocampal sulcus. -

Staging of Alzheimer Disease-Associated Neurowbrillary Pathology Using Parayn Sections and Immunocytochemistry

Acta Neuropathol (2006) 112:389–404 DOI 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z METHODS REPORT Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neuroWbrillary pathology using paraYn sections and immunocytochemistry Heiko Braak · Irina AlafuzoV · Thomas Arzberger · Hans Kretzschmar · Kelly Del Tredici Received: 8 June 2006 / Revised: 21 July 2006 / Accepted: 21 July 2006 / Published online: 12 August 2006 © Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Assessment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)- revised here by adapting tissue selection and process- related neuroWbrillary pathology requires a procedure ing to the needs of paraYn-embedded sections (5–15 m) that permits a suYcient diVerentiation between initial, and by introducing a robust immunoreaction (AT8) for intermediate, and late stages. The gradual deposition hyperphosphorylated tau protein that can be processed of a hyperphosphorylated tau protein within select on an automated basis. It is anticipated that this neuronal types in speciWc nuclei or areas is central to revised methodological protocol will enable a more the disease process. The staging of AD-related neuroW- uniform application of the staging procedure. brillary pathology originally described in 1991 was per- formed on unconventionally thick sections (100 m) Keywords Alzheimer’s disease · NeuroWbrillary using a modern silver technique and reXected the pro- changes · Immunocytochemistry · gress of the disease process based chieXy on the topo- Hyperphosphorylated tau protein · Neuropathologic graphic expansion of the lesions. To better meet the staging · Pretangles demands of routine laboratories this procedure is Introduction This study was made possible by funding from the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and BrainNet Europe II (European Commission LSHM-CT-2004- The development of intraneuronal lesions at selec- 503039). -

MITOCW | MIT9 14S09 Lec36-Mp3

MITOCW | MIT9_14S09_lec36-mp3 The following content is provided under a Creative Commons license. Your support will help MIT OpenCourseWare continue to offer high quality educational resources for free. To make a donation or view additional materials from hundreds of MIT courses, visit MIT OpenCourseWare at ocw.mit.edu. PROFESSOR: So this class, we will talk about some of the cell types in the neocortex and the way they're connected. We'll talk about different regions of neocortex, that is actually after it had experienced, in evolution, a lot of expansion, and we're just going to deal with mammalian cortex in small animals, like rodents, and human being. And then we'll talk a little bit about some of the major fibers in and out of the membrain. We've talked about those already, but I want to review them to make sure that they're in your mind. And then we'll get, at least, to an introduction of thalamocortical connections, which again, you've had some because when we talked about visual system, we talked about the genicular body rejection in the visual area, primary visual cortex, the auditory cortex. We talked about medial geniculate body, somatosensory has been talked about several times. We talked about the ventral nucleus. All right. So what are the two most commonly encountered classes in the cortical cells? The most characteristic cell type in the neocortex is the pyramidal cell, and this is what they look like. This is Brodel's simplification of the pyramidal cell that shows their major characteristics, a cell body with a sort of pyramidal shape in an apical dendrite that goes up towards the surface, and many of these cells send their apical dendrite all the way up to the surface where they arborize right up in layer one. -

Role of Lifestyle in Neuroplasticity and Neurogenesis in an Aging Brain

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.10639 Role of Lifestyle in Neuroplasticity and Neurogenesis in an Aging Brain Reeju Maharjan 1, 2 , Liliana Diaz Bustamante 3 , Kyrillos N. Ghattas 4 , Shahbakht Ilyas 5, 6 , Reham Al-Refai 7 , Safeera Khan 4 1. Neurology, V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Kharkiv, UKR 2. Neurology, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA 3. Family Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA 4. Internal Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA 5. Medicine and Surgery, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, PAK 6. Surgery, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA 7. Pathology, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA Corresponding author: Reeju Maharjan, [email protected] Abstract Neuroplasticity is the brain's ability to transform its shape, adapt, and develop a new neuronal connection provided with a new stimulus. The stronger the electrical stimulation, the robust is the transformation. Neurogenesis is a complex process when the new neuronal blast cells present in the dentate gyrus divide in the hippocampus. We collected articles from the past 11 years for review, using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) strategy from PubMed. Quality appraisal was done for each research article using various assessment tools. A total of 24 articles were chosen, applying all the mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria and reviewed. The reviewed studies emphasized that modifiable lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise should be implemented as an intervention in the elderly for healthy aging of the brain, as the world's aging population is going to be increased, leading to the expansion of health care and cost. -

Implications of Aging Neuronal Gain Control on Cognition

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Neuromodulation and aging: implications of aging neuronal gain control on cognition 1,2 3,4 Shu-Chen Li and Anna Rieckmann The efficacy of various transmitter systems declines with 30-year gain in physical health is, however, not necess- advancing age. Of particular interest, various pre-synaptic and arily accompanied by cognitive fitness and mental well- post-synaptic components of the dopaminergic system being into old age. Faced with the rapid growth of aging change across the human lifespan; impairments in these populations worldwide and an ever-expanding prevalence components play important roles in cognitive deficits of dementia, understanding brain aging and aging-related commonly observed in the elderly. Here, we review evidence cognitive declines has become a key challenge for neuro- from recent multimodal neuroimaging, pharmacological and science and psychology in the 21st century. genetic studies that have provided new insights for the associations among dopamine functions, aging, functional Brain aging is characterized by multiple neurobiological brain activations and behavioral performance across key changes including losses of white matter integrity, cortical cognitive functions, ranging from working memory and thickness and grey matter volumes, metabolic activity, episodic memory to goal-directed learning and decision and neurotransmitter functions (e.g. see [4 ] for an over- making. Specifically, we discuss these empirical findings in the view). The focus of the current review will be on aging- context of an established neurocomputational theory of aging related declines in neurotransmitter functions and the neuronal gain control. We also highlight gaps in the current associated implications for cognitive functioning. -

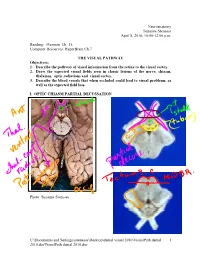

Visualpath Dental 2010.Jnt

Neuroanatomy Suzanne Stensaas April 8, 2010, 10:00-12:00 p.m. Reading: Waxman Ch. 15, Computer Resources: HyperBrain Ch 7 THE VISUAL PATHWAY Objectives: 1. Describe the pathway of visual information from the retina to the visual cortex. 2. Draw the expected visual fields seen in classic lesions of the nerve, chiasm, thalamus, optic radiations and visual cortex. 3. Describe the blood vessels that when occluded could lead to visual problems, as well as the expected field loss. I. OPTIC CHIASM PARTIAL DECUSSATION Photo: Suzanne Stensaas C:\Documents and Settings\sstensaas\Desktop\dental visual 2010\VisualPath dental 1 2010.docVisualPath dental 2010.doc II. OPTIC TRACT Ganglion cell axons diverge A. 90% go to Lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of thalamus (the retino- geniculo-calcarine path ) B. 10% go to Superior colliculus and pretectum (the retinocollicular path for reflexes) C. The hypothalamus for circadian rhythms (not to be discussed) III. THALAMIC RELAY NUCLEUS -- the LATERAL GENICULATE NUCLEUS OR BODY A. Specific retinotopic projection. B. Six layers. Three layers get input from from each eye. Thalamus Red LGN LGN Nucleus C:\Documents and Settings\sstensaas\Desktop\dental visual 2010\VisualPath dental 2 2010.docVisualPath dental 2010.doc The optic tract projects to the LGN Crainial Nerves, Wilson-Pauwels et al., 1988 IV. OPTIC RADIATIONS A. Retinotopic organization from the LGN neurons to the cortex. B. Axons of neurons in the lateral geniculate form the optic radiations = geniculocalcarine tract. The retinotopic organization is maintained. 1. Some loop forward over inferior (or temporal) horn of lateral ventricle = Meyer's Loop 2. Other axons take a more direct posterior course through the deep parietal white matter.