Turtle-Excellence FI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SRC Reading Countsnov2012all

Title Author Name Lexile Levels 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 47 Mosley, Walter 860 47 Mosley, Walter 860 1632 Flint, Eric 650 1776 McCullough, David 1300 1968 Kaufman, Michael T. 1310 1984 Orwell, George 1090 2030 Zuckerman, Amy 990 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 11-Sep-01 Santella, Andrew 890 Rodrigues, Carmen 690 "A" Is for Abigail Cheney, Lynne 1030 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Burns, Marilyn 800 (Re)cycler McLaughlin, Lauren 630 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 ...y entonces llegó un perro DeJong, Meindert ¡Audaz! Miller, Amy 640 ¡Béisbol! Winter, Jonah 960 ¡Por la gran cuchara de cuerno! Fleischman, Sid 700 ¡Qué ruido! Brodmann, A. ¡Relámpagos! Hopping, Lorraine Jean ¿De qué estoy hecho? Bennett, David ¿Me quieres, mamá? Joosse, Barbara M. 570 ¿Qué animal es? Balzola, S. 240 ¿Qué son los científicos? Gelman, Rita Golden 100 ¿Quién ayuda en casa? Alcántara, R. 580 ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 ¿Quién dice no a las drogas? Alcántara, R. ¿Quién es de aquí? Knight, Margy Burns 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Boy Freeman, Martha 790 10 Best Animal Camouflages, The Lindsey, Cameron 950 10 Best Animal Helpers, The Carnelos, Melissa 990 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 10 Best Plays, The Nyman, Debbie 920 10 Best TV Game Shows, The Quan-D'Eramo, Sandra 960 10 Best Underdog Stories In Sports, The Goh, Michelle 1000 10 Boldest Explorers, The Scholastic, 1020 10 Bravest Everyday Heroes, The Beardsley, Sally 910 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 10 Coolest Flying Machines, The Cond, Sandie 960 10 Coolest Wonders Of The Universe, The Samuel, Nigel 1020 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 10 Days: Anne Frank Colbert, David 980 10 Days: Benjamin Franklin Colbert, David 960 10 Days: Martin Luther King Jr. -

Youth Collection

TITLE AUTHOR LAST NAME AUTHOR FIRST NAME PUBLISHER AWARDS QUANTITY 1,2,3 A Finger Play Harcourt Brace & Company 2 1,2,3 in the Box Tarlow Ellen Scholastic 1,2,3 to the Zoo Carle Eric Philomel Books 10 Little Fingers and 10 Little Toes Fox & Oxenbury Mem & Helen HMH 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby Mona Scholastic 50 Great Make-It, Take-It Projects Gilbert LaBritta Upstart Books A Band of Angels Hopkinson Deborah Houghton Mifflin Company A Band of Angels Mathis Sharon Houghton Mifflin Company A Beauty of a Plan Medearis Angela Houghton Mifflin Company A Birthday Basket for Tia Mora Pat Alladin Books A Book of Hugs Ross Dave Harper Collins Publishers A Boy Called Slow: The True Story of Sitting Bull Bruchac Joseph Philomel Books A Boy Named Charlie Brown Shulz Charles Metro Books A Chair for My Mother Williams Vera B. Mulberry Books A Corner of the Universe Freeman Don Puffin Books A Day With a Mechanic Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day With Air Traffic Controllers Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day with Wilbur Robinson Joyce William Scholastic A Flag For All Brimner Larry Dane Scholastic A Gathering of Days Mosel Arlene Troll Associates Caldecott A Gathering of Old Men Williams Karen Mullberry Paperback Books A Girl Name Helen Keller Lundell Margo Scholastic A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich Bawden Nina Dell/Yearling Books A House Spider's Life Himmelman John Division of Grolier Publishing A Is For Africa Onyefulu Ifeoma Silver Burdett Ginn A Kitten is a Baby Cat Blevins Wiley Scholastic A Long Way From Home Wartski Maureen Signet A Million Fish … More or Less Byars Betsy Scholastic A Mouse Called Wolf King-Smith Dick Crown Publishers A Picture Book of Rosa Parks Keats Ezra Harper Trophy A Piggie Christmas Towle Wendy Scholastic Inc. -

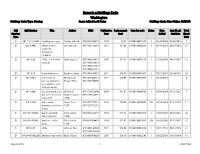

Items in a Holdings Code Washington Holdings Code Type: Owning Items Added in All Dates Holdings Code: Non-Fiction (WESNF)

Items in a Holdings Code Washington Holdings Code Type: Owning Items Added in All Dates Holdings Code: Non-Fiction (WESNF) Call Call Number Title Author ISBN Publication Replacement Item Barcode Status Date Last Check Total Number Year Cost Added Out Date Check Type Outs D 001.5 St STEWIG Sending messages Stewig, John W. 9780395243879 1978 $6.95 30180100015365 I 01/12/2010 03/02/2012 5 D 001.9 ARN Monster hunt : Arnosky, Jim. 9781423130284 2011 $17.00 30180100092638 I 03/14/2013 04/27/2015 24 exploring mysterious creatures D 001.9 DE UFOs : the Roswell DeMolay, Jack. 9781404234031 2007 $17.95 30180100018112 I 12/18/2009 04/16/2015 23 incident 9781404234031 9781404221567 9781404221567 D 001.9 ER Alien abductions Erickson, Justin 9781600145827 2011 $18.00 30180200001471 I 10/21/2011 02/04/2015 39 D 001.9 MA Top 10 worst MacDonald, 9781433940712 2011 $10.00 30180100093057 T 02/13/2015 0 spooky mysteries : Fiona, 1958- 9781433940705 you wouldn't want to know about! D 001.9 OM Are you afraid yet? : O'Meara, 9781554532940 2009 $17.95 30180100094683 I 10/24/2014 05/11/2015 7 the science behind Stephen James, 9781554532957 scary stuff 1956- D 001.9 OW Half-human Owen, Ruth, 9781617727252 2013 $20.00 30180100094865 CO 10/24/2014 05/13/2015 11 monsters and other 1967- 9781617727252 fiends D 001.9 Pe PERRY Giants and wild, Perry, Janet, 9780836824377 1999 $13.95 30180100017072 I 01/07/2010 04/20/2015 28 hairy monsters 1960- D 001.9 Pe PERRY Monsters of the Perry, Janet, 9780836824407 1999 $13.95 30180100019011 CO 01/20/2010 05/13/2015 35 deep 1960- -

North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND WESTERN PACIFIC SEA TURTLE Cooperative Research & Management Workshop VOLUME II North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles Coordinated & Edited by Irene Kinan Sponsored by the 1164 Bishop Street, Suite 1400 Honolulu, Hawaii, 96813, USA www.wpcouncil.org/Protected To provide a forum to gather and exchange information, promote collaboration, and maintain momentum for research, conservation and management of Pacific sea turtle populations. Document Citation Kinan, I. (editor). 2006. Proceedings of the Second Western Pacific Sea Turtle Cooperative Research and Management Workshop. Volume II: North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles. March 2-3, 2005, Honolulu, HI. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council: Honolulu, HI, USA. Editors’ note The papers presented at the workshop and contained in these proceedings have been edited and formatted for consistency, with only minor changes to language, syntax, and punctuation. The authors’ bibliographic, abbreviation and writing styles, however, have generally been retained. Several presenters did not submit a written paper, or submitted only an abstract to the meeting. In these instances, a summary was produced from transcripts of their presentations. The opinions of the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. A report of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council printed pursuant to National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA05NMF441092 3 Table of Contents 5 PREFACE 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 INDO-PACIFIC MARINE TURTLES 8 WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS 9 WORKSHOP SUMMARY: A Collaboration of Partnerships Around the Pacific 11 INTRODUCTION: Research Story of the North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtle Irene Kinan and Dr. Wallace J. Nichols 13 Nesting Beach Management of Eggs and Pre-emergent Hatchlings of North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Japan Dr. -

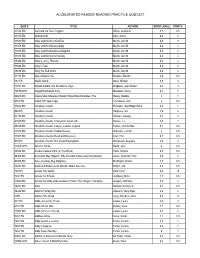

AR Title List

ACCELERATED READER READING PRACTICE QUIZ LIST QUIZ # TITLE AUTHOR BOOK LEVEL POINTS 21536 EN Aani and the Tree Huggers Atkins, Jeannine 3.3 0.5 23270 EN Abandoned! Dale, Jenny 4.6 3 19880 EN Abby and the Best Kid Ever Martin, Ann M. 4.4 3 19378 EN Abby and the Mystery Baby Martin, Ann M. 4.6 4 19385 EN Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Martin, Ann M. 4.5 4 19373 EN Abby and the Secret Society Martin, Ann M. 4.9 4 19346 EN Abby's Lucky Thirteen Martin, Ann M. 4.9 4 19868 EN Abby's Twin Martin, Ann M. 4.2 3 19874 EN Abby the Bad Sport Martin, Ann M. 4.9 3 11151 EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 2.6 0.5 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 5.9 3 13701 EN Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Wagoner, Jean Brown 4.2 3 105789 EN Abigail the Breeze Fairy Meadows, Daisy 4.1 1 86635 EN Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows, The Dadey, Debbie 4 1 4181 EN About 100 Years Ago Trumbauer, Lisa 2 0.5 18652 EN Abraham Lincoln D'Aulaire, Ingri/Edgar Parin 5.2 1 866 EN Abraham Lincoln Hargrove, Jim 7.9 2 54155 EN Abraham Lincoln Sullivan, George 5.3 2 43029 EN Abraham Lincoln: A Great American Life Owens, L.L. 3.4 1 45920 EN Abraham Lincoln: Lawyer, Leader, Legend Fontes, Justine/Ron 5.3 0.5 31812 EN Abraham Lincoln (Pebble Books) Schaefer, Lola M. 2 0.5 13551 EN Abraham Lincoln (Read and Discover) Usel, T.M. -

Sea Turtles of the Caribbean

SWOT report Volume XV The State of the World’s Sea Turtles SPECIAL FEATURE Sea Turtles of the Caribbean INSIDE: INDIAN OCEAN LOGGERHEADS DRONES FOR CONSERVATION JAGUARS AND MORE … A bubble forms as a green turtle exhales at the surface. © Ben J. Hicks/benjhicks.com. FRONT COVER: A leatherback turtle finishes her nesting process as day breaks in Grande Riviere, Trinidad. © Ben J. Hicks/benjhicks.com 2 | SWOT REPORT SEATURTLESTATUS.ORG | 1 2 | SWOT REPORT Editor’s Note No Sea Turtle Is an Island ise men and women throughout history have shown us that, “there is Wpower in unity and there is power in numbers” (Martin Luther King Jr., 1963). That is certainly the case with the State of the World’s Sea Turtles (SWOT) program, the world’s largest volunteer network of sea turtle researchers, conservationists, and enthusiasts. This volume of SWOT Report unifies an enormous cast: from the hundreds of researchers in more than 20 countries, whose collective efforts can be seen in the first-ever global-scale map of loggerhead sea turtle telemetry (pp. 32–33), to the beach workers from the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) and beyond, whose labors are seen in this issue’s maps of sea turtle biogeography (pp. 24–27). As you peruse these cartographic works of art, reflect for a moment on the time, effort, and passion that went into each of those tiny, tinted polygons of telemetry data or the myriad multicolored circles of nest abundance. Together they represent the labors of a multitude of beach workers, synergistically amassed to bring big-picture visualizations of sea turtle natural history to life as never before. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6q8939qt Author Sprinceana, Andreea Iulia Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama By Andreea Iulia Sprinceana A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair Professor Michael Iarocci Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2014 Copyright Andreea Iulia Sprinceana, 2014 All rights reserved. Abstract Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama by Andreea Iulia Sprinceana Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair This dissertation explores the manifestations, uses and appropriations of history in key Spanish plays from the 1950s to the present. The relationship between the stage and history casts new light on Spain’s most critical phases in recent history. The authors studied were and are conscious of making history under the dictatorship, during the Transition and at the dawn of the 21st century. As instruments of civic action, their plays perform that awareness and invite spectators to recognize themselves as players in the process. The dissertation opens with a comparative analysis of plays written by Antonio Buero Vallejo and Alfonso Sastre between the 1950s and the Transition (1977). While scholars have tended to contrast these two playwrights focusing on their responses to censorship, I propose that Buero and Sastre gravitated towards a poetics of forgiveness through the model of the failed tragic hero. -

Forging a Future for Pacific Sea Turtles

ForgingForging aa FutureFuture forfor PacificPacific SeaSea TurtlesTurtles Pacific sea turtles tell us a story about our ocean world… We must act now Pacific sea turtles connect the human and the extinction of these modern dinosaurs and Many sea turtle populations are so depleted ocean worlds. Turtles show us that although pave the way for a new era of open ocean that further loss may be irreversible. All five the ocean seems endless and vast, its diversity ecosystem conservation. species of Pacific sea turtles are listed in the and vulnerability is concentrated in focused, IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered, identifiable areas. After surviving over 100 Sea turtles need our help Endangered or Vulnerable, and all marine Parallels between million years, we are watching these ancient turtles are included in Appendix I of CITES If current trends continue, leatherback reptiles go extinct as a result of humans’ (Convention on International Trade in and loggerhead sea turtles will probably go inability to understand them and adequately Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and sea turtles and extinct in the Pacific in our lifetime. Eastern protect them. Many people are overwhelmed Flora). Some species are doing better than Pacific hawksbills are likely past the point of by the thought of conserving a species that others, but they are all at mere fractions of deep sea corals no return, while green turtles and olive Ridleys migrates across vast oceans given the gauntlet former population sizes. For most of their are at a fraction of their former populations. At first glance, deep sea corals and sea turtles seem nothing of threats turtles face. -

The Following National and Local Organizations, Cities/Counties, And

The following national and local organizations, cities/counties, and elected officials support addressing the multi-billion dollar backlog plaguing our National Park System: NATIONAL SUPPORT The Pew Charitable Trusts OneVet OneVoice U.S. Conference of Mayors United Steel Workers (USW) National Parks Conservation Association Outdoor Industry Association National Association of Counties International Inbound Travel Association Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians Kappa Alpha Phi Fraternity, Inc. Associated General Contractors of America Independent Electrical Contractors, Inc. National Trust for Historic Preservation International Dark-Sky Association Public Lands Alliance International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Vet Voice Foundation American Alpine Club Preservation Action American Council of Engineering Companies Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in Historic American Alpine Institute Preservation Hispanic Access Fund American Society of Civil Engineers Land Improvement Contractors of America International Mountain Bicycling Association Hispanics Enjoying Camping Hiking & the The Corps Network Outdoors (HECHO) American Forests Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks American Hiking Society American Canoe Association American Institute of Architects Latino Outdoors American Supply Association American Coatings Association Archaeological Institute of America Mechanical Contractors Association of America Association for the Study of African American American Cultural Resources Association Life and History Living Landscape -

BIOLOGY and CONSERVATION of SEA TURTLES in BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO by Wallace J. Nichols Copyright © Wall

1 BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF SEA TURTLES IN BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO by Wallace J. Nichols _____________________ Copyright © Wallace J. Nichols 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN WILDLIFE ECOLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 3 2 Before the final oral defense the student obtains the Approval Pages from the Degree Certification Office. Original signatures are required on both final copies. 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author SIGNED: ________________________________ 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In my first meeting as a graduate student I sat on one side of a large rectangular table in Room 1 in the basement of the Biological Sciences East Building at the University of Arizona. Facing me were an ichthyologist (Dr. Donald Thomson), a wildlife ecologist (Dr. -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Volusia Schools MANAGEMENT READING BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL POINTS "A" Is for Abigail Cheney, Lynne 1030 4.6 3 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Burns, Marilyn 800 6.5 3 'N Sync (Celebrity Bios) Laslo, Cynthia N/A 5.6 3 'Night, Mother Norman, Marsha N/A 7.2 6 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 4.9 10 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 5.4 4 'Twas The Day Before Zoo Day Ipcizade, Catherine N/A 2.3 1 (Re)cycler McLaughlin, Lauren 630 4.5 16 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 5.5 23 ...y entonces llegó un perro DeJong, Meindert N/A 5.6 6 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 4.6 1 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 5.2 15 1,2 Y 3 ¡A La Caja! Tarlow, Ellen N/A 1.1 1 1,2,3 In The Box Tarlow, Ellen N/A 1.2 1 10 Best Animal Camouflages, Th Lindsey, Cameron 950 7.4 6 10 Best Animal Helpers, The Carnelos, Melissa 990 8.4 6 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 5.5 6 10 Best Plays, The Nyman, Debbie 920 6.4 6 10 Best Things… Dad Loomis, Christine N/A 1.6 1 10 Best TV Game Shows, The Quan-D'Eramo, Sandra 960 7.3 6 10 Best Underdog Stories In Sp Goh, Michelle 1000 8.5 6 10 Boldest Explorers, The Scholastic 1020 8.6 6 10 Bravest Everyday Heroes, Th Beardsley, Sally 910 6.3 6 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 5.6 6 10 Coolest Flying Machines, Th Cond, Sandie 960 7.5 6 10 Coolest Wonders Of The Univ Samuel, Nigel 1020 8.6 6 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 8.5 7 10 Days: Anne Frank Colbert, David 980 7.4 6 10 Days: Benjamin Franklin Colbert, David 960 7.5 7 10 Days: Martin Luther King Jr Colbert, David 1060 9.5 7 10 Days: Thomas Edison Colbert, David 1050 9.4 7 10 Deadliest Plants, The Littlefield, Angie 940 7.3 6 10 Deadliest Predators On Land Jenkins, Jennifer Meghan 970 7.6 6 10 Deadliest Sea Creatures, Th Scholastic 1010 8.6 6 10 Deadliest Snakes, The Scholastic 970 7.6 6 10 Fat Turkeys Johnston, Tony 320 1.7 1 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 2.4 1 Printed by: Mary Ellis Page 1 of 93 Printed on: 07/08/13 Copyright © Scholastic Inc. -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Forest Hills School District MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT "A" Is for Abigail Cheney, Lynne 1030 4.6 Q 3 2,655 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Burns, Marilyn 800 6.5 T 3 1,317 'N Sync (Celebrity Bios) Laslo, Cynthia N/A 5.6 T 3 2,940 'Night, Mother Norman, Marsha N/A 7.2 NR 6 15,792 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 4.9 N/A 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 5.4 N/A 4 4,224 'Twas The Day Before Zoo Day Ipcizade, Catherine N/A 2.3 N/A 1 634 (Re)cycler McLaughlin, Lauren 630 4.5 N/A 16 63,418 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 5.5 N/A 23 98,676 ...y entonces llegó un perro DeJong, Meindert N/A 5.6 N/A 6 0 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 4.6 N/A 1 415 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 5.2 N/A 15 58,937 1,2 Y 3 ¡A La Caja! Tarlow, Ellen N/A 1.1 A 1 24 1,2,3 In The Box Tarlow, Ellen N/A 1.2 A 1 23 10 Best Animal Camouflages, Th Lindsey, Cameron 950 7.4 N/A 6 7,686 10 Best Animal Helpers, The Carnelos, Melissa 990 8.4 N/A 6 7,393 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 5.5 N/A 6 8,332 10 Best Plays, The Nyman, Debbie 920 6.4 N/A 6 10,044 10 Best Things… Dad Loomis, Christine N/A 1.6 F 1 155 10 Best TV Game Shows, The Quan-D'Eramo, Sandra 960 7.3 N/A 6 9,787 10 Best Underdog Stories In Sp Goh, Michelle 1000 8.5 N/A 6 9,083 10 Boldest Explorers, The Scholastic 1020 8.6 N/A 6 8,908 10 Bravest Everyday Heroes, Th Beardsley, Sally 910 6.3 N/A 6 8,575 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 5.6 N/A 6 7,660 10 Coolest Flying Machines, Th Cond, Sandie