Forging a Future for Pacific Sea Turtles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beach Dynamics and Impact of Armouring on Olive Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys Olivacea) Nesting at Gahirmatha Rookery of Odisha Coast, India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 45(2), February 2016, pp. 233-238 Beach dynamics and impact of armouring on olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) nesting at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast, India Satyaranjan Behera1, 2, Basudev Tripathy3*, K. Sivakumar2, B.C. Choudhury2 1Odisha Biodiversity Board, Regional Plant Resource Centre Campus, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar-15 2Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, PO Box 18, Chandrabani, Dehradun – 248 001, India. 3Zoological Survey of India, Prani Vigyan Bhawan, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 (India) *[E. mail:[email protected]] Received 28 March 2014; revised 18 September 2014 Gahirmatha arribada beach are most dynamic and eroding at a faster rate over the years from 2008-09 to 2010-11, especially during the turtles breeding seasons. Impact of armouring cement tetrapod on olive ridley sea turtle nesting beach at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast has also been reported in this study. This study documented the area of nesting beach has reduced from 0.07 km2to 0.06 km2. Due to a constraint of nesting space, turtles were forced to nest in the gap of cement tetrapods adjacent to the arribada beach and get entangled there, resulting into either injury or death. A total of 209 and 24 turtles were reported to be injured and dead due to placement of cement tetrapods in their nesting beach during 2008-09 and 2010-11 respectively. Olive ridley turtles in Odisha are now exposed to many problems other than fishing related casualty and precautionary measures need to be taken by the wildlife and forest authorities to safeguard the Olive ridleys and their nesting habitat at Gahirmatha. -

La Terre Ne Nous Appartient Pas, Ce Sont Nos Enfants Qui Nous La Prêtent”

Réserve Naturelle Nationale de Saint-Martin Le Journal “La terre ne nous appartient pas, ce sont nos enfants qui nous la prêtent” Trimestriel n°29 juillet 2017 Sommaire Megara 2017 : troisième édition: 4/5 Megara 2017: Mission #3 Un atelier en faveur des récifs et 6 A workshop In Support of Reefs des herbiers and Plant Beds Une thèse en faveur des herbiers 7 A Thesis About Plant Beds Un plan structuré contre la 8 A Solid Plan To Fight Hydrocarbon pollution aux hydrocarbures Pollution Des données conservées 9 Conserving Data Forever and Ever Des échasses clandestines 10 Clandestine Birds Nesting Sauvetage d’une tortue fléchée 11 Saving An Injured Turtle Un filet au Galion 12 Fishnet at Galion Saisie d’un filet de 300 mètres 12 300-meter Fishnet Seized Double saisie pour deux pêcheurs 13 Double Trouble For Two Fishermen Quads dans la Réserve 14 Quads in the Réserve: Poisson-lion et ciguatera 15 Lionfish and Ciguatera: Le centre équestre déménagera 16 Galion Equestrian Center To Move 17 bouées de mouillage à Tintamare 17 17 Buoys at Tintamare De nouveaux panneaux, interactifs 18 New Interactive Signage Bye bye Romain Renoux ! 19 Bye bye Romain Renoux! Toutes les réserves en Martinique 20/21 Nature Reserves Met In Martinique Cours de SVT à Pinel 22 Science Classes at Pinel Des régatiers et des baleines 23 Regattas VS Whales Un nouveau parc marin. Bravo Aruba ! 24/25 A New Marine Park. Bravo Aruba! Le Forum UE-PTOM à Aruba 26 UE-PTOM Forum in Aruba BEST : 2 beaux projets à Anguilla 27/30 BEST: 2 Winning Projects in Anguilla Réunion sur les baleines à bosse 31/32 Metting about Humpback Whales BEST : dernier appel à projets 32/33 BEST: Last Call For Projects 2 Edito à nos visiteurs des sites préservés, des plages propres, des eaux de baignade de qualité, ils ne viendront plus ! Le maintien de notre biodiversi- té et la préservation des différents écosystèmes marins et terrestres à Saint Martin sont une pri- orité. -

Threats to Sea Turtles Artificial Lighting

Threats to Sea Turtles Artificial Lighting Artificial lighting is a significant sea turtle conservation problem. Sea turtle hatchlings instinctively move towards the brightest light when they hatch – on a natural beach, this is the night sky over the ocean. The artificial lighting causes the hatchlings to become disoriented, and ultimately leads to their death. Below are two maps. The “Artificial Lighting” map is a satellite image of the lights that are visible at night in Florida from space. The “Florida County” map will be used for reference. You will also need your “Sea Turtle Nesting Data” from an earlier lesson. Directions: Using the data provided identify areas where artificial lighting has the greatest impact on sea turtle hatchlings. Artificial Lighting Map Lightly shaded areas (yellow) - Lights visible at night from space Compare the “Artificial Lighting” map with the blank county map below. Color in the counties which have the most visible night lights from space. County Map Compare this data with data you collected earlier of the nesting sites of Green, Leatherback and Loggerhead turtles. Green Nesting Map Leatherback Nesting Map Loggerhead Nesting Map Questions 1. Describe the relationship between the nesting data and the artificial lighting data. ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Background on Sea Turtles

Background on Sea Turtles Five of the seven species of sea turtles call Virginia waters home between the months of April and November. All five species are listed on the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants and classified as either “Threatened” or “Endangered”. It is estimated that anywhere between five and ten thousand sea turtles enter the Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer months. Of these the most common visitor is the loggerhead followed by the Kemp’s ridley, leatherback and green. The least common of the five species is the hawksbill. The Loggerhead is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle often reaching weights of 1000 lbs. However, the ones typically sighted in Virginia’s waters range in size from 50 to 300 lbs. The diet of the loggerhead is extensive including jellies, sponges, bivalves, gastropods, squid and shrimp. While visiting the Bay waters the loggerhead dines almost exclusively on horseshoe crabs. Virginia is the northern most nesting grounds for the loggerhead. Because the temperature of the nest dictates the sex of the turtle it is often thought that the few nests found in Virginia are producing predominately male offspring. Once the male turtles enter the water they will never return to land in their lifetime. Loggerheads are listed as a “Threatened” species. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is the second most frequent visitor in Virginia waters. It is the smallest of the species off Virginia’s coast reaching a maximum weight of just over 100 lbs. The specimens sited in Virginia are often less than 30 lbs. -

Issue Number 118 October 2007 ISSN 0839-7708 in THIS

Issue Number 118 October 2007 Green turtle hatchling from Turkey with extra carapacial scutes (see pp. 6-8). Photo by O. Türkozan IN THIS ISSUE: Editorial: Conservation Conflicts, Conflicts of Interest, and Conflict Resolution: What Hopes for Marine Turtle Conservation?..........................................................................................L.M. Campbell Articles: From Hendrickson (1958) to Monroe & Limpus (1979) and Beyond: An Evaluation of the Turtle Barnacle Tubicinella cheloniae.........................................................A. Ross & M.G. Frick Nest relocation as a conservation strategy: looking from a different perspective...................O. Türkozan & C. Yılmaz Linking Micronesia and Southeast Asia: Palau Sea Turtle Satellite Tracking and Flipper Tag Returns......S. Klain et al. Morphometrics of the Green Turtle at the Atol das Rocas Marine Biological Reserve, Brazil...........A. Grossman et al. Notes: Epibionts of Olive Ridley Turtles Nesting at Playa Ceuta, Sinaloa, México...............................L. Angulo-Lozano et al. Self-Grooming by Loggerhead Turtles in Georgia, USA..........................................................M.G. Frick & G. McFall IUCN-MTSG Quarterly Report Announcements News & Legal Briefs Recent Publications Marine Turtle Newsletter No. 118, 2007 - Page 1 ISSN 0839-7708 Editors: Managing Editor: Lisa M. Campbell Matthew H. Godfrey Michael S. Coyne Nicholas School of the Environment NC Sea Turtle Project A321 LSRC, Box 90328 and Earth Sciences, Duke University NC Wildlife Resources Commission Nicholas School of the Environment 135 Duke Marine Lab Road 1507 Ann St. and Earth Sciences, Duke University Beaufort, NC 28516 USA Beaufort, NC 28516 USA Durham, NC 27708-0328 USA E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 252-504-7648 Fax: +1 919 684-8741 Founding Editor: Nicholas Mrosovsky University of Toronto, Canada Editorial Board: Brendan J. -

Reproductive Physiology of Nesting Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys Coriacea) at Las Baulas National Park, Costa Rica

Chelolliall COllserwuioll (lnd Biology, 1996,2(2):230- 236 © 1996 by Chelonian Research Foundation Reproductive Physiology of Nesting Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) at Las Baulas National Park, Costa Rica i 2 3 4 DAVID C. ROSTAL , FRANK V. PALADIN0 , RHONDA M. PATTERSON , AND JAMES R. SPOTILA I Department of Biology, Georgia Southern Uni versity, Statesboro, Georgia 30460 USA [Fax: 912-681-0845; E-mail: [email protected]}; 2Department of Biology, Indiana-Purdue University, Fort Wayne, Indiana 46805 USA ; 3Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843 USA ; 4Department o{Bioscience and Biotechnology, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 USA ABSTRACT. - The reproductive physiology of nesting leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) was studied at Playa Grande, Costa Rica, from 1992 to 1994 during November, December, and January. Ultrasonography indicated that 82 % of nesting females had mature preovulatory ovaries in November, 40 % in December, and 23 % in January. Mean follicular diameter was 3.33 ±0.02 cm and did not vary significantly through the nesting season. Plasma testosterone and estradiol levels measured by radioimmunoassay correlated strongly with reproductive condition. No correlation, however, was observed between reproductive condition and plasma progesterone levels. Testoster one declined from 2245 ± 280 pglml at the beginning of the nesting cycle to 318 ± 89 pglml at the end of the nesting cycle. Estradiol declined in a similar manner. Plasma calcium levels were constant throughout the nesting cycle. Vitellogenesis appeared complete prior to the arrival of the female at the nesting beach. Dermochelys coriacea is a seasonal nester displaying unique variations (e.g., 9 to 10 day internesting interval, yolkless eggs) on the basic chelonian pattern. -

SRC Reading Countsnov2012all

Title Author Name Lexile Levels 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 47 Mosley, Walter 860 47 Mosley, Walter 860 1632 Flint, Eric 650 1776 McCullough, David 1300 1968 Kaufman, Michael T. 1310 1984 Orwell, George 1090 2030 Zuckerman, Amy 990 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 11-Sep-01 Santella, Andrew 890 Rodrigues, Carmen 690 "A" Is for Abigail Cheney, Lynne 1030 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Burns, Marilyn 800 (Re)cycler McLaughlin, Lauren 630 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 ...y entonces llegó un perro DeJong, Meindert ¡Audaz! Miller, Amy 640 ¡Béisbol! Winter, Jonah 960 ¡Por la gran cuchara de cuerno! Fleischman, Sid 700 ¡Qué ruido! Brodmann, A. ¡Relámpagos! Hopping, Lorraine Jean ¿De qué estoy hecho? Bennett, David ¿Me quieres, mamá? Joosse, Barbara M. 570 ¿Qué animal es? Balzola, S. 240 ¿Qué son los científicos? Gelman, Rita Golden 100 ¿Quién ayuda en casa? Alcántara, R. 580 ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 ¿Quién dice no a las drogas? Alcántara, R. ¿Quién es de aquí? Knight, Margy Burns 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Boy Freeman, Martha 790 10 Best Animal Camouflages, The Lindsey, Cameron 950 10 Best Animal Helpers, The Carnelos, Melissa 990 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 10 Best Plays, The Nyman, Debbie 920 10 Best TV Game Shows, The Quan-D'Eramo, Sandra 960 10 Best Underdog Stories In Sports, The Goh, Michelle 1000 10 Boldest Explorers, The Scholastic, 1020 10 Bravest Everyday Heroes, The Beardsley, Sally 910 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 10 Coolest Flying Machines, The Cond, Sandie 960 10 Coolest Wonders Of The Universe, The Samuel, Nigel 1020 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 10 Days: Anne Frank Colbert, David 980 10 Days: Benjamin Franklin Colbert, David 960 10 Days: Martin Luther King Jr. -

Youth Collection

TITLE AUTHOR LAST NAME AUTHOR FIRST NAME PUBLISHER AWARDS QUANTITY 1,2,3 A Finger Play Harcourt Brace & Company 2 1,2,3 in the Box Tarlow Ellen Scholastic 1,2,3 to the Zoo Carle Eric Philomel Books 10 Little Fingers and 10 Little Toes Fox & Oxenbury Mem & Helen HMH 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby Mona Scholastic 50 Great Make-It, Take-It Projects Gilbert LaBritta Upstart Books A Band of Angels Hopkinson Deborah Houghton Mifflin Company A Band of Angels Mathis Sharon Houghton Mifflin Company A Beauty of a Plan Medearis Angela Houghton Mifflin Company A Birthday Basket for Tia Mora Pat Alladin Books A Book of Hugs Ross Dave Harper Collins Publishers A Boy Called Slow: The True Story of Sitting Bull Bruchac Joseph Philomel Books A Boy Named Charlie Brown Shulz Charles Metro Books A Chair for My Mother Williams Vera B. Mulberry Books A Corner of the Universe Freeman Don Puffin Books A Day With a Mechanic Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day With Air Traffic Controllers Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day with Wilbur Robinson Joyce William Scholastic A Flag For All Brimner Larry Dane Scholastic A Gathering of Days Mosel Arlene Troll Associates Caldecott A Gathering of Old Men Williams Karen Mullberry Paperback Books A Girl Name Helen Keller Lundell Margo Scholastic A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich Bawden Nina Dell/Yearling Books A House Spider's Life Himmelman John Division of Grolier Publishing A Is For Africa Onyefulu Ifeoma Silver Burdett Ginn A Kitten is a Baby Cat Blevins Wiley Scholastic A Long Way From Home Wartski Maureen Signet A Million Fish … More or Less Byars Betsy Scholastic A Mouse Called Wolf King-Smith Dick Crown Publishers A Picture Book of Rosa Parks Keats Ezra Harper Trophy A Piggie Christmas Towle Wendy Scholastic Inc. -

Turtle Tracks Miami-Dade County Marine Extension Service

Turtle Tracks Miami-Dade County Marine Extension Service Florida Sea Grant Program DISTURBING A SEA TURTLE NEST IS A VIOLATION 4 OF STATE AND FEDERAL LAWS. 2 TURTLE TRACKS What To Do If You See A Turtle 1 3 SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION IN MIAMI-DADE COUNTY If you observe an adult sea turtle or hatchling sea turtles on the beach, please adhere to the following rules and guidelines: 1. It is normal for sea turtles to be crawling on the beach on summer nights. DO NOT report normal crawling or nesting (digging or laying eggs) to the Florida Marine Patrol unless the turtle is in a dangerous situation or has wandered off the beach. 1. Leatherback (on a road, in parking lot, etc.) 2. Stay away from crawling or nesting sea turtles. Although the 2. Kemp’s Ridley urge to observe closely will be great, please resist. Nesting is a 3. Green critical stage in the sea turtle’s life cycle. Please leave them 4. Loggerhead undisturbed. U.S. GOVERNMENTPRINTINGOFFICE: 1999-557-736 3. DO REPORT all stranded (dead or injured) turtles to the This information is a cooperative effort on behalf of the following organizations to Florida Marine Patrol. help residents of Miami-Dade County learn about sea turtle conservation efforts in 4. NEVER handle hatchling sea turtles. If you observe hatchlings this coastal region of the state. wandering away from the ocean or on the beach, call: NATIONAL Florida Marine Pat r ol 1-800- DIAL-FMP (3425-367) SAVE THE SEATURTLE FOUNDATION MIAMI-DADE COUNTY SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION PROGRAM 4419 West Tradewinds Avenue "To Protect Endangered or Threatened Marine Turtles for Fort Lauderdale, Floirda 33308 Future Generations" Phone: 954-351-9333 efore 1980, there was no documented sea Fax: 954-351-5530 Toll Free: 877-Turtle3 turtle activity in Mia m i - D ade County, due B mainly to the lack of an adequate beach-nesting Information has been drawn from “Sea Turtle Conservation Program“, a publication of the Broward County Department of Planning and Environmental Protection, habitat. -

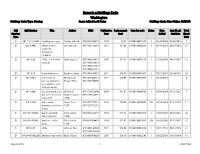

Items in a Holdings Code Washington Holdings Code Type: Owning Items Added in All Dates Holdings Code: Non-Fiction (WESNF)

Items in a Holdings Code Washington Holdings Code Type: Owning Items Added in All Dates Holdings Code: Non-Fiction (WESNF) Call Call Number Title Author ISBN Publication Replacement Item Barcode Status Date Last Check Total Number Year Cost Added Out Date Check Type Outs D 001.5 St STEWIG Sending messages Stewig, John W. 9780395243879 1978 $6.95 30180100015365 I 01/12/2010 03/02/2012 5 D 001.9 ARN Monster hunt : Arnosky, Jim. 9781423130284 2011 $17.00 30180100092638 I 03/14/2013 04/27/2015 24 exploring mysterious creatures D 001.9 DE UFOs : the Roswell DeMolay, Jack. 9781404234031 2007 $17.95 30180100018112 I 12/18/2009 04/16/2015 23 incident 9781404234031 9781404221567 9781404221567 D 001.9 ER Alien abductions Erickson, Justin 9781600145827 2011 $18.00 30180200001471 I 10/21/2011 02/04/2015 39 D 001.9 MA Top 10 worst MacDonald, 9781433940712 2011 $10.00 30180100093057 T 02/13/2015 0 spooky mysteries : Fiona, 1958- 9781433940705 you wouldn't want to know about! D 001.9 OM Are you afraid yet? : O'Meara, 9781554532940 2009 $17.95 30180100094683 I 10/24/2014 05/11/2015 7 the science behind Stephen James, 9781554532957 scary stuff 1956- D 001.9 OW Half-human Owen, Ruth, 9781617727252 2013 $20.00 30180100094865 CO 10/24/2014 05/13/2015 11 monsters and other 1967- 9781617727252 fiends D 001.9 Pe PERRY Giants and wild, Perry, Janet, 9780836824377 1999 $13.95 30180100017072 I 01/07/2010 04/20/2015 28 hairy monsters 1960- D 001.9 Pe PERRY Monsters of the Perry, Janet, 9780836824407 1999 $13.95 30180100019011 CO 01/20/2010 05/13/2015 35 deep 1960- -

Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta Caretta (Linnaeus 1758)

OF THE BI sTt1cAL HE LOGGERHEAD SEA TURTLE CAC-Err' CARETTA(LINNAEUS 1758) Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biological Report This publication series of the Fish and Wildlife Service comprises reports on the results of research, developments in technology, and ecological surveys and inventories of effects of land-use changes on fishery and wildlife resources. They may include proceedings of workshops, technical conferences, or symposia; and interpretive bibliographies. They also include resource and wetland inventory maps. Copies of this publication may be obtained from the Publications Unit, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC 20240, or may be purchased from the National Technical Information Ser- vice (NTIS), 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dodd, C. Kenneth. Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. (Biological report; 88(14) (May 1988)) Supt. of Docs. no. : I 49.89/2:88(14) Bibliography: p. 1. Loggerhead turtle. I. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. II. Title. III. Series: Biological Report (Washington, D.C.) ; 88-14. QL666.C536D63 1988 597.92 88-600121 This report may be cit,-;c1 as follows: Dodd, C. Kenneth, Jr. 1988. Synopsis of the biological data on the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus 1758). U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv., Biol. Rep. 88(14). 110 pp. Biological Report 88(14) May 1988 Synopsis of the Biological Dataon the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta caretta(Linnaeus 1758) by C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Ecology Research Center 412 N.E.