Sea Turtles of the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrimp Fishing in Mexico

235 Shrimp fishing in Mexico Based on the work of D. Aguilar and J. Grande-Vidal AN OVERVIEW Mexico has coastlines of 8 475 km along the Pacific and 3 294 km along the Atlantic Oceans. Shrimp fishing in Mexico takes place in the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, both by artisanal and industrial fleets. A large number of small fishing vessels use many types of gear to catch shrimp. The larger offshore shrimp vessels, numbering about 2 212, trawl using either two nets (Pacific side) or four nets (Atlantic). In 2003, shrimp production in Mexico of 123 905 tonnes came from three sources: 21.26 percent from artisanal fisheries, 28.41 percent from industrial fisheries and 50.33 percent from aquaculture activities. Shrimp is the most important fishery commodity produced in Mexico in terms of value, exports and employment. Catches of Mexican Pacific shrimp appear to have reached their maximum. There is general recognition that overcapacity is a problem in the various shrimp fleets. DEVELOPMENT AND STRUCTURE Although trawling for shrimp started in the late 1920s, shrimp has been captured in inshore areas since pre-Columbian times. Magallón-Barajas (1987) describes the lagoon shrimp fishery, developed in the pre-Hispanic era by natives of the southeastern Gulf of California, which used barriers built with mangrove sticks across the channels and mouths of estuaries and lagoons. The National Fisheries Institute (INP, 2000) and Magallón-Barajas (1987) reviewed the history of shrimp fishing on the Pacific coast of Mexico. It began in 1921 at Guaymas with two United States boats. -

Mustique 50Th Anniversary 16 – 22 July 2018 Message from the Prime Minister

MUSTIQUE 50TH ANNIVERSARY 16 – 22 JULY 2018 MESSAGE FROM THE PRIME MINISTER Dear Friends, On June 28, 2018, the Parliament of St Vincent a sensible give-and-take which grounds and the Grenadines passed, unanimously, an enduring harmony, despite occasional a Bill to amend “The Mustique Act” which dissonance. extends until December 31, 2039, a unique agreement between the government and The We treasure the home-owners in Mustique, Mustique Company Limited. The amendment their friends, and visitors as part of our also contains a provision for a further twenty- Vincentian family. We thank everyone who year extension on reasonable terms to be makes this enduring partnership work in the later concluded between both parties. In this interest of all. way, the 50th Anniversary of The Mustique Company was thus celebrated by our nation’s I personally look forward to the 50th Parliament. Anniversary celebrations. I heartily congratulate The Mustique Company, Over the past fifty years, the basic framework its owners, directors, management, and agreement between the Mustique Company employees on the magnificent journey, thus far. and St Vincent and the Grenadines has been supported by successive governments I wish The Mustique Company, the people of simply because it accords with the people’s Mustique, and the people of St Vincent and the interest. This remarkable, and mutually- Grenadines further accomplishments! beneficial, partnership has evolved as a model for sustainable and environmentally- sensitive development. The letter and spirit The Honourable -

SRC Reading Countsnov2012all

Title Author Name Lexile Levels 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 47 Mosley, Walter 860 47 Mosley, Walter 860 1632 Flint, Eric 650 1776 McCullough, David 1300 1968 Kaufman, Michael T. 1310 1984 Orwell, George 1090 2030 Zuckerman, Amy 990 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 11-Sep-01 Santella, Andrew 890 Rodrigues, Carmen 690 "A" Is for Abigail Cheney, Lynne 1030 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Burns, Marilyn 800 (Re)cycler McLaughlin, Lauren 630 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 ...y entonces llegó un perro DeJong, Meindert ¡Audaz! Miller, Amy 640 ¡Béisbol! Winter, Jonah 960 ¡Por la gran cuchara de cuerno! Fleischman, Sid 700 ¡Qué ruido! Brodmann, A. ¡Relámpagos! Hopping, Lorraine Jean ¿De qué estoy hecho? Bennett, David ¿Me quieres, mamá? Joosse, Barbara M. 570 ¿Qué animal es? Balzola, S. 240 ¿Qué son los científicos? Gelman, Rita Golden 100 ¿Quién ayuda en casa? Alcántara, R. 580 ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 ¿Quién dice no a las drogas? Alcántara, R. ¿Quién es de aquí? Knight, Margy Burns 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Boy Freeman, Martha 790 10 Best Animal Camouflages, The Lindsey, Cameron 950 10 Best Animal Helpers, The Carnelos, Melissa 990 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 10 Best Plays, The Nyman, Debbie 920 10 Best TV Game Shows, The Quan-D'Eramo, Sandra 960 10 Best Underdog Stories In Sports, The Goh, Michelle 1000 10 Boldest Explorers, The Scholastic, 1020 10 Bravest Everyday Heroes, The Beardsley, Sally 910 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 10 Coolest Flying Machines, The Cond, Sandie 960 10 Coolest Wonders Of The Universe, The Samuel, Nigel 1020 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 10 Days: Anne Frank Colbert, David 980 10 Days: Benjamin Franklin Colbert, David 960 10 Days: Martin Luther King Jr. -

Youth Collection

TITLE AUTHOR LAST NAME AUTHOR FIRST NAME PUBLISHER AWARDS QUANTITY 1,2,3 A Finger Play Harcourt Brace & Company 2 1,2,3 in the Box Tarlow Ellen Scholastic 1,2,3 to the Zoo Carle Eric Philomel Books 10 Little Fingers and 10 Little Toes Fox & Oxenbury Mem & Helen HMH 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby Mona Scholastic 50 Great Make-It, Take-It Projects Gilbert LaBritta Upstart Books A Band of Angels Hopkinson Deborah Houghton Mifflin Company A Band of Angels Mathis Sharon Houghton Mifflin Company A Beauty of a Plan Medearis Angela Houghton Mifflin Company A Birthday Basket for Tia Mora Pat Alladin Books A Book of Hugs Ross Dave Harper Collins Publishers A Boy Called Slow: The True Story of Sitting Bull Bruchac Joseph Philomel Books A Boy Named Charlie Brown Shulz Charles Metro Books A Chair for My Mother Williams Vera B. Mulberry Books A Corner of the Universe Freeman Don Puffin Books A Day With a Mechanic Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day With Air Traffic Controllers Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day with Wilbur Robinson Joyce William Scholastic A Flag For All Brimner Larry Dane Scholastic A Gathering of Days Mosel Arlene Troll Associates Caldecott A Gathering of Old Men Williams Karen Mullberry Paperback Books A Girl Name Helen Keller Lundell Margo Scholastic A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich Bawden Nina Dell/Yearling Books A House Spider's Life Himmelman John Division of Grolier Publishing A Is For Africa Onyefulu Ifeoma Silver Burdett Ginn A Kitten is a Baby Cat Blevins Wiley Scholastic A Long Way From Home Wartski Maureen Signet A Million Fish … More or Less Byars Betsy Scholastic A Mouse Called Wolf King-Smith Dick Crown Publishers A Picture Book of Rosa Parks Keats Ezra Harper Trophy A Piggie Christmas Towle Wendy Scholastic Inc. -

Sea Level Rise and Land Use Planning in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Pará

Water, Water Everywhere: Sea Level Rise and Land Use Planning in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Pará Thomas E. Bassett and Gregory R. Scruggs © 2013 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper The findings and conclusions of this Working Paper reflect the views of the author(s) and have not been subject to a detailed review by the staff of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Contact the Lincoln Institute with questions or requests for permission to reprint this paper. [email protected] Lincoln Institute Product Code: WP13TB1 Abstract The Caribbean and northern coastal Brazil face severe impacts from climate change, particularly from sea-level rise. This paper analyses current land use and development policies in three Caribbean locations and one at the mouth of the Amazon River to determine if these policies are sufficient to protect economic, natural, and population resources based on current projections of urbanization and sea-level rise. Where policies are not deemed sufficient, the authors will address the question of how land use and infrastructure policies could be adjusted to most cost- effectively mitigate the negative impacts of climate change on the economies and urban populations. Keywords: sea-level rise, land use planning, coastal development, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Pará, Brazil About the Authors Thomas E. Bassett is a senior program associate at the American Planning Association. He works on the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas grant from the U.S. Department of State as well as the domestic Community Assistance Program. Thomas E. Bassett 1030 15th Street NW Suite 750W Washington, DC 20005 Phone: 202-349-1028 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Gregory R. -

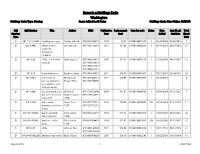

Items in a Holdings Code Washington Holdings Code Type: Owning Items Added in All Dates Holdings Code: Non-Fiction (WESNF)

Items in a Holdings Code Washington Holdings Code Type: Owning Items Added in All Dates Holdings Code: Non-Fiction (WESNF) Call Call Number Title Author ISBN Publication Replacement Item Barcode Status Date Last Check Total Number Year Cost Added Out Date Check Type Outs D 001.5 St STEWIG Sending messages Stewig, John W. 9780395243879 1978 $6.95 30180100015365 I 01/12/2010 03/02/2012 5 D 001.9 ARN Monster hunt : Arnosky, Jim. 9781423130284 2011 $17.00 30180100092638 I 03/14/2013 04/27/2015 24 exploring mysterious creatures D 001.9 DE UFOs : the Roswell DeMolay, Jack. 9781404234031 2007 $17.95 30180100018112 I 12/18/2009 04/16/2015 23 incident 9781404234031 9781404221567 9781404221567 D 001.9 ER Alien abductions Erickson, Justin 9781600145827 2011 $18.00 30180200001471 I 10/21/2011 02/04/2015 39 D 001.9 MA Top 10 worst MacDonald, 9781433940712 2011 $10.00 30180100093057 T 02/13/2015 0 spooky mysteries : Fiona, 1958- 9781433940705 you wouldn't want to know about! D 001.9 OM Are you afraid yet? : O'Meara, 9781554532940 2009 $17.95 30180100094683 I 10/24/2014 05/11/2015 7 the science behind Stephen James, 9781554532957 scary stuff 1956- D 001.9 OW Half-human Owen, Ruth, 9781617727252 2013 $20.00 30180100094865 CO 10/24/2014 05/13/2015 11 monsters and other 1967- 9781617727252 fiends D 001.9 Pe PERRY Giants and wild, Perry, Janet, 9780836824377 1999 $13.95 30180100017072 I 01/07/2010 04/20/2015 28 hairy monsters 1960- D 001.9 Pe PERRY Monsters of the Perry, Janet, 9780836824407 1999 $13.95 30180100019011 CO 01/20/2010 05/13/2015 35 deep 1960- -

Turtle-Excellence FI

K_\C\^\e[f]BXl`cX he ancient Hawaiians tell the story of a magical turtle named Kauila, the daughter of Honupookea, who was born on the black sand beach of Punaluu Kon the island of Hawaii. Kauila made her home at the bottom of a freshwater spring that the Hawaiians named after her, called Ka wai hu o Kauila – the rising waters of Kauila. Children would come to play in the spring and Kauila would transform herself into a girl to watch over them. Kauila became the guardian of the children and the life-giving spring that produced fresh water for the people of Punaluu. Cover: Photo mosaic of a leatherback hatchling in Papua New Guinea. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: 2 Sea Turtle Conservation in the Pacific 4 An Introduction to Pacific Sea Turtles 6 Facing the Hazards of Humankind SEA TURTLES OF THE PACIFIC: 8 A Shared History GREEN SEA TURTLES OF THE PACIFIC: 11 Saving the Hawaiian Green Turtle NEW FRONTIERS: 15 The Challenge Ahead 17 Pacific Ocean Ambassador 21 Turning the Tide for the Leatherback SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES: 26 Learning from Turtles 28 Gearing Up 30 Thinking Like a Turtle 34 Observing Turtles 38 Q&A: Interview with Kitty Simonds 41 Marine Turtle Conservation Through National Policy Implementation THE COLLECTIVE SEA TURTLE PROGRAM: 43 Summary of All Sea Turtle Related Projects 1 Hawaii–A Center for Pacific Sea Turtle Research & Conservation INTRODUCTION: Sea Turtle Conservation ationally and globally, sea turtle conservation and recovery remain critical issues as virtually all sea Nturtle populations are designated as either threatened or endangered by the U.S. -

C-Map by Jeppesen Mm3d Coverage

C-MAP BY JEPPESEN MM3D COVERAGE NORTH AMERICA WVJNAM021MAP – Canada North & East MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM021MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM022MAP – USA East Coast and Bahamas MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM022MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 9 WVJNAM023MAP – Gulf of Mexico, Great Lakes & Rivers MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM023MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM024MAP – West Coast & Hawaii MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM024MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 10 WVNJNAM025MAP – Canada West MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM025MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM026MAP – Great Lakes & Canadian Maritimes MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM026MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 11 WVJNAM027MAP – Central America & Caribbean MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM027MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM028MAP - Alaska MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM028MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 12 MWVJNAM033MAP – Atl. Coast, Gulf of MX & Caribbean MM3D File Name: (2files) SDVJNAM033NMAP0x.dbv and SDVJNAM033SMAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $600.00 – MegaWide MWVJNAM035MAP – Pacific Coast and Central America MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM035NMAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $600.00 –MegaWide 13 SOUTH AMERICA WVJSAM500MAP – Costa Rica to Chile to Falklands MM3D File Name: SDVJSAM500MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 –Wide WVJSAM501MAP – Gulf of Paria to Cape Horn MM3D File Name: SDVJSAM501MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 –Wide 14 MWVJSAM504MAP – South America & US Gulf Coast MM3D File Name: SDVJSAM504MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $600.00 –MegaWide MAX LAKES WVJNAM017MAP – MAX Lakes North MM3D File Name: -

I Imagine the Enthusiasm of Tatiana Copeland's Resounding

If a princess invited you to her soirée, wouldn’t you go? I imagine the enthusiasm of Tatiana Copeland’s resounding “yes!” when the notoriously charismatic and playful Princess Margaret, sister to Queen Elizabeth II, first invited her to the private island paradise of Mustique in the West Indies. Copeland is a jet-setting polyglot, philanthropist, and succesful businesswoman with an impressive family lineage that includes the likes of Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. Along with her equally well-connected husband, Gerret (a scion of the prominent DuPont family), Tatiana has returned many times to Mustique since that first royal invitation about four decades ago. And with good reason: The remote island, with its overall ambiance of joie de vivre and laid-back elegance, continues to be the Copeland family antidote for stress. “At first we rented other people’s villas, and over time, we stayed at nearly every one on the island,” Tatiana tells me as we sip libations by an infinity pool at Toucan Hill, a Moroccan-inspired villa she built and finished in 2004. She gestures to the nearly 360-degree, panoramic view of cobalt sea, just as the sun sets, a fat orange ball exploding into purple octopus arms across the sky. A satisfied look consumes her face. “Finally, we just had to build our own fantastical dream.” Visitors can rent Toucan Hill, one of 100+ villas that comprise Mustique Island & Villas, which itself is owned by the island’s various homeowners. The infinity pool at Toucan Villa in Mustique. One of the Caribbean’s best-kept secrets, 1,400-acre Mustique island has drawn glitterati for decades. -

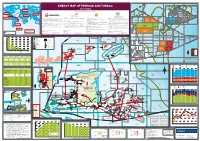

View the Energy Map of Trinidad and Tobago, 2017 Edition

Trinidad and Tobago LNG export destinations 2015 (million m3 of LNG) Trinidad and Tobago deepwater area for development 60°W 59°W 58°W Trinidad and Tobago territorial waters ENERGY MAP OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 1000 2000 m m 2017 edition GRENADA BARBADOS Trinidad and Tobago 2000m LNG to Europe A tlantic Ocean 2.91 million m3 LNG A TLANTIC Caribbean 2000m 20 Produced by Petroleum Economist, in association with 00 O CEAN EUROPE Sea m Trinidad and Tobago 2000m LNG to North America NORTH AMERICA Trinidad and Tobago 5.69 million m3 LNG LNG to Asia 3 GO TTDAA 30 TTDAA 31 TTDAA 32 BA 1.02 million m LNG TO Trinidad and Tobago OPEN OPEN OPEN 12°N LNG to MENA 3 1.90 million m LNG ASIA Trinidad and Tobago CARIBBEAN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 2000m LNG to Caribbean Atlantic LNG Company profile Company Profile Company profile Company Profile 3 Established by the Government of Trinidad and Tobago in August 1975, The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) is an BHP Billiton is a leading global resources company with a Petroleum Business that includes exploration, development, production and marketing Shell has been in Trinidad and Tobago for over 100 years and has played a major role in the development of its oil and gas industry. Petroleum Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (Petrotrin) is an integrated Oil and Gas Company engaged in the full range of petroleum 3.84 million m LNG internationally investment-graded company that is strategically positioned in the midstream of the natural gas value chain. -

North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND WESTERN PACIFIC SEA TURTLE Cooperative Research & Management Workshop VOLUME II North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles Coordinated & Edited by Irene Kinan Sponsored by the 1164 Bishop Street, Suite 1400 Honolulu, Hawaii, 96813, USA www.wpcouncil.org/Protected To provide a forum to gather and exchange information, promote collaboration, and maintain momentum for research, conservation and management of Pacific sea turtle populations. Document Citation Kinan, I. (editor). 2006. Proceedings of the Second Western Pacific Sea Turtle Cooperative Research and Management Workshop. Volume II: North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles. March 2-3, 2005, Honolulu, HI. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council: Honolulu, HI, USA. Editors’ note The papers presented at the workshop and contained in these proceedings have been edited and formatted for consistency, with only minor changes to language, syntax, and punctuation. The authors’ bibliographic, abbreviation and writing styles, however, have generally been retained. Several presenters did not submit a written paper, or submitted only an abstract to the meeting. In these instances, a summary was produced from transcripts of their presentations. The opinions of the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. A report of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council printed pursuant to National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA05NMF441092 3 Table of Contents 5 PREFACE 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 INDO-PACIFIC MARINE TURTLES 8 WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS 9 WORKSHOP SUMMARY: A Collaboration of Partnerships Around the Pacific 11 INTRODUCTION: Research Story of the North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtle Irene Kinan and Dr. Wallace J. Nichols 13 Nesting Beach Management of Eggs and Pre-emergent Hatchlings of North Pacific Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Japan Dr. -

![Weber Et Al., 2001A; Pérez Et Al., 2001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9412/weber-et-al-2001a-p%C3%A9rez-et-al-2001-2439412.webp)

Weber Et Al., 2001A; Pérez Et Al., 2001]

PUBLICATIONS Tectonics RESEARCH ARTICLE Tectonic inversion in the Caribbean-South American 10.1002/2014TC003665 plate boundary: GPS geodesy, seismology, Key Points: and tectonics of the Mw 6.7 22 April • The 22 April 1997 Mw 6.7 Tobago earthquake inverted a low-angle 1997 Tobago earthquake thrust fault • Seismology, GPS, and modeling John C. Weber1, Halldor Geirsson2, Joan L. Latchman3, Kenton Shaw1, Peter La Femina2, resolve coseismic slip, fault geometry, 4 3 1 4,5 and moment Shimon Wdowinski , Machel Higgins , Christopher Churches , and Edmundo Norabuena • Coseismic slip subsided Tobago and 1 2 moved it NNE Department of Geology, Grand Valley State College, Allendale, Michigan, USA, Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA, 3Seismic Research Centre, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, 4RSMAS-Geodesy Lab, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA, 5Now at Instituto Geofisica del Peru, Lima, Peru Correspondence to: J. C. Weber, [email protected] Abstract On 22 April 1997 the largest earthquake recorded in the Trinidad-Tobago segment of the Caribbean-South American plate boundary zone (Mw 6.7) ruptured a shallow (~9 km), ENE striking (~250° Citation: azimuth), shallowly dipping (~28°) dextral-normal fault ~10 km south of Tobago. In this study, we describe Weber, J. C., H. Geirsson, J. L. Latchman, this earthquake and related foreshock and aftershock seismicity, derive coseismic offsets using GPS data, K. Shaw, P. La Femina, S. Wdowinski, M. Higgins, C. Churches, and E. Norabuena and model the fault plane and magnitude of slip for this earthquake. Coseismic slip estimated at our episodic (2015), Tectonic inversion in the GPS sites indicates movement of Tobago 135 ± 6 to 68 ± 6 mm NNE and subsidence of 7 ± 9 to 0 mm.