Confinement: a Memoir of Abortion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Hello, Dolly!" at Auditorium Theatre, Jan. 27

AUDITORIUM THEATRE ROCHESTER JANUARY 27 BROAD'lMAY TO FEBRUARY 1 THEATRE LEAGUE 1969 YVONNE DECARLO m HELLO, gOLL~I llng1na1ly D1rected and ChoreogrJphPd by GOWER CHDIPIOII Th1s Pr oductiOn D1rected by LUCIA VICTOR ~tenens FEATURING OUR SATURDAY NITE SPECIAL Prime Rib of Beef Au Jus Baked Potato with Sour Cream & Chives Vegetable - Salad - Coffee $3.95 . ALSO MANY OTHER DELICIOUS ITEMS Stop in for dinner before the show or after the show for a late evening anack SERVING 7 DAYS & NITES FROM 11 A.M. till 2 A.M. 1501 UNIVERSITY AVE . EXTENSION PLENTY OF FlEE PAIICING For Reservations Call: 271-9635 or 271-9494 PARTY AND BANQUET ACCOMMODATIONS Consult Us For Your Banquets And Part i es . • • we w i ll be glad to hove you . Wm. Fisher, Budd Filippo & Ken Gaston proudly present YVONNE DE CARLO in The New York Critics Circle & Tony Award Winn1ng Mus1cal "HELLO, DOLLVI 11 Book IJy Music & Lyrics by MICHAEL STEW ART JERRY HERMAN Based on the originc~l play by Thornton Wilder also starring DON DE LEO with Kathleen Devine George Cavey Rick Grimaldi Suzanne Simon David Gary Althea Rose Edie Pool Norman Fredericks Settings Designed by Lighting Consultant Costumes by Oliver Smith Gerald Richland freddy Wittop Dance & Incidental Music Orchestration by Arrangements by Musical Dirt!cliun by Phillip J. Lang Peter Howard Gil Bowers [)ances Staged for this Production hy Jack Craig Original Choreography & Direction by GOWER CHAMPION This Production Staged by Lucia Victor PHIL'S PANTRYS J A Y ' S "REAL DELICATESSENS" Fresh Sliced Cold Meats D I N E R Home Made Salads & Baked Beans lWO LOCAnONS 2612 W. -

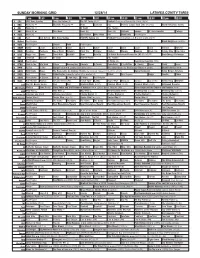

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: the Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2017 A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support Stephanie J. Begun University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Begun, Stephanie J., "A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1293. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1293 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support ___________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Social Work University of Denver ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________ by Stephanie J. Begun June 2017 Advisor: Kimberly Bender, Ph.D., M.S.W. ©Copyright by Stephanie J. Begun 2017 All Rights Reserved Author: Stephanie J. Begun Title: A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support Advisor: Kimberly Bender, Ph.D., M.S.W. -

The Sand Canyon Review 2013

The Sand Canyon Review 2013 1 Dear Reader, The Sand Canyon Review is back for its 6th issue. Since the conception of the magazine, we have wanted to create an outlet for artists of all genres and mediums to express their passion, craft, and talent to the masses in an accessible way. We have worked especially hard to foster a creative atmosphere in which people can express their identity through the work that they do. I have done a lot of thinking about the topic of identity. Whether someone is creating a poem, story, art piece, or multimedia endeavor, we all put a piece of ourselves, a piece of who we are into everything we create. The identity of oneself is embedded into not only our creations but our lives. This year the goal ofThe Sand Canyon Review is to tap into this notion, to go beyond the words on a page, beyond the color on the canvas, and discover the artist behind the piece. This magazine is not only a collection of different artists’ identities, but it is also a part of The Sand Canyon Review team’s identity. On behalf of the entire SCR staff, I wish you a wonderful journey into the lives of everyone represented in these pages. Sincerely, Roberto Manjarrez, Managing Editor MANAGING EDITOR Roberto Manjarrez POETRY SELectION TEAM Faith Pasillas, Director Brittany Whitt Art SELectION TEAM Mariah Ertl, Co-Director Aurora Escott, Co-Director Nicole Hawkins Christopher Negron FIT C ION SELectION TEAM Annmarie Stickels, Editorial Director BILL SUMMERS VICTORIA CEBALLOS Nicole Hakim Brandon Gnuschke GRAphIC DesIGN TEAM Jillian Nicholson, Director Walter Achramowicz Brian Campell Robert Morgan Paul Appel PUBLIC RELATIONS The SCR STAFF COPY EDITORS Bill Summers Nicole Hakim COVER IMAGE The Giving Tree, Owen Klaas EDITOR IN CHIEF Ryan Bartlett 2013 EDITION3 Table of Contents Poetry Come My Good Country You Know 8 Mouse Slipping Through the Knot I Saw Sunrise From My Knees 10 From This Apartment 12 L. -

The Piano Duet Play-Along Series Gives You the • I Dreamed a Dream • in My Life • on My Own • Stars

1. Piano Favorites 13. Movie Hits 9 great duets: Candle in the Wind • Chopsticks • Don’t 8 film favorites: Theme from E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial) Know Why • Edelweiss • Goodbye Yellow Brick Road • • Forrest Gump – Main Title (Feather Theme) • The Heart and Soul • Let It Be • Linus and Lucy • Your Song. Godfather (Love Theme) • The John Dunbar Theme • Moon 00290546 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 River • Romeo and Juliet (Love Theme) • Theme from Schindler’s List • Somewhere, My Love. 2. Movie Favorites 00290560 Book/CD Pack ...........................$14.95 8 classics: Chariots of Fire • The Entertainer • Theme from Jurassic Park • My Father’s Favorite • My Heart Will Go 14. Les Misérables On (Love Theme from Titanic) • Somewhere in Time • 8 great songs from the musical: Bring Him Home • Castle on Somewhere, My Love • Star Trek® the Motion Picture. a Cloud • Do You Hear the People Sing? • A Heart Full of Love The Piano Duet Play-Along series gives you the • I Dreamed a Dream • In My Life • On My Own • Stars. flexibility to rehearse or perform piano duets 00290547 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 00290561 Book/CD Pack ...........................$16.95 anytime, anywhere! Play these delightful tunes 3. Broadway for Two 10 songs from the stage: Any Dream Will Do • Blue Skies 15. God Bless America® & Other with a partner, or use the accompanying CDs • Cabaret • Climb Ev’ry Mountain • If I Loved You • Okla- to play along with either the Secondo or Primo Songs for a Better Nation homa • Ol’ Man River • On My Own • There’s No Business 8 patriotic duets: America, the Beautiful • Anchors part on your own. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

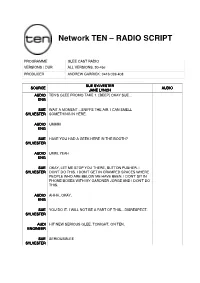

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

Drama, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation in Early Modern

RUDE MECHANICALS: STAGING LABOR IN THE EARLY MODERN ENGLISH THEATER by Matthew Kendrick BA, English, University of New Hampshire, 2005 MA, English, University of Rochester, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Matthew Kendrick It was defended on September 29, 2011 and approved by John Twyning, Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Jennifer Waldron, Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Nicholas Coles, Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Rachel Trubowitz, Professor, Department of English, University of New Hampshire Dissertation Co-Chair: Jennifer Waldron, Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Co-Chair: John Twyning, Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Matthew Kendrick 2011 iii Rude Mechanicals: Staging Labor in the Early Modern English Theater Matthew Kendrick, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This dissertation explores the relationship between the early modern theater and changing conceptions of labor. Current interpretations of the theater’s economic dimensions stress the correlation between acting and vagrant labor. I build on these approaches to argue that the theater’s connection to questions of labor was far more dynamic than is often thought. In particular, I argue that a full understanding of the relationship between the theater and labor requires that we take into account the theater’s guild origins. If theatricality was often associated with features of vagrant labor, especially cony-catching and rogue duplicity, the theater also drew significantly from medieval guild practices that valued labor as a social good and a creative force. -

Fum FURT TO-NIGHT

AMUSEMENTS BROADWAY & 11TH ST, fuM FURT TO-NIGHT. 1Y SHOE GO. 1 : and S I'D K. UNION SQUARE, ACADEMY OF DESIGN Paintings Basement Salesroom. ACADEMY OF MUSIC.Last of the Rolians and Place West Four kUteentn Street Between Broadway University AMERIOAN Die Meistersinger 'ill BIJOU In Paradise BKOADWAY The Ghetto ."] CASINO The Rounders of iii The Great Department Store ex( I CRITERION The Girl from Maxim's 9,000 yards Silk, Shoes. i DALY'S The King's Musketeer of 2 to 16 clusively for We are New york's La rgest and Sellers DEWEY Vaudeville lengths yards c Buyers Ef)EN MUSEE World in Wax EMPIRE The Tyranny,of Tears consisting of Fancy TafFe FIFTH AVENUE BecRy Sharp The Korker of 14TH STREET A Young Wife tas,.in plaid, check, stripe GARRICK My Innocent Boy GARDEN Rupert of Hentzau ' Shoe, GRAND OPERA HOUSE.A Grip of Steel corded, floral, warp print HARLEM OPERA HOUSE Phroso I and a of novo HOUSEKEE PING HERALD SQUARE The Only Way ed, variety GOODS.I IIUBER'S MUSEUM Vaudeville I iC°r ^en> HURT1G A SEAMON'S Vaudeville designs. Light, medianj KEITH'S UNION SQUARE.... Vaudeville Pillow Tic! KNICKERBOCKER. ..Cyrano tie Bergerac and dark shades. Sheets, Cases, Muslins. <ings, Bnn;ets, Comfortables, Quilts, KOSTER <fc BIAL'S Vaudeville Table Linens, Fia " bread and butter '* LYCEUM Miss Hobbs Peai1 2,50 Towels, Towellings, nnels,.the among MAD. SQ. THEA. Why Smith Left Home Black, Ducliesse, Housekeepers' requirements.Of ea ch and all of these we show extraordinary MANHATTAN, de Brocades A Stranger in a Strange Land Soie, Taffetas, assortments of all qualities, and throiugh our great purchases for cash can and METROPOLIS The Sporting Duchess MURRAY HILL The Highest Bidder Gros grain, Faille and Ar do sell so low that frequently our seiiUngprices are belcw .hose competitors pay NEW YORK. -

In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT

re p resenting the american theatre DRAMATISTS by publishing and licensing the works PLAY SERVICE, INC. of new and established playwrights. atpIssuel 4,aFall 1999 y In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT aggie Edson — the celebrated playwright who is so far Off- Broadway, she’s below the Mason-Dixon line — is performing a Mdaily ritual known as Wiggle Down. " Tapping my toe, just tapping my toe" she sings, to the tune of "Singin' in the Rain," before a crowd of kindergarteners at a downtown elementary school in Atlanta. "What a glorious feeling, I'm — nodding my head!" The kids gleefully tap their toes and nod themselves silly as they sing along. "Give yourselves a standing O!" Ms. Edson cries, when the song ends. Her charges scramble to their feet and clap their hands, sending their arms arcing overhead in a giant "O." This willowy 37-year-old woman with tousled brown hair and a big grin couldn't seem more different from Dr. Vivian Bearing, the brilliant, emotionally remote English professor who is the heroine of her play WIT — which has won such unanimous critical acclaim in its small Off- Broadway production. Vivian is a 50-year-old scholar who has devoted her life to the study of John Donne's "Holy Sonnets." When we meet her, she is dying of very placement of a comma crystallizing mysteries of life and death for ovarian cancer. Bald from chemotherapy, she makes her entrance clad Vivian and her audience. For this feat, one critic demanded that Ms. Edson in a hospital gown, dragging an IV pole. -

Albany, NY - March 10-12, 2017 Results Solo Intermediate ~ Mini PLACEMENT ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE STUDIO NAME SCORE

Albany, NY - March 10-12, 2017 Results Solo Intermediate ~ Mini PLACEMENT ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE STUDIO NAME SCORE 9TH 345 OUTSIDE LOOKING IN (ELLIE STIMSON) Leslie School of Dance 237.5 8TH 344 FRIEND LIKE ME (SADIEMAE SCHWALB) The Dance Experience 243 7TH 319 MONEY (SABRINA O'CONNOR) Leslie School of Dance 244 6TH 196 SHINE ON YOUR SHOES (BAILEY KELLER) Eleanor's School of Dance 250 6TH 219 I'M GONNA SIT RIGHT DOWN (ADDISON FURZE) JDC Dance Center 250 Ballet and All That Jazz, 5TH 331 KEEP ON DANCING (SYDNEY GIER) 251 LLC 4TH 211 HONEYBUN (AVA JONES) Eleanor's School of Dance 252 4TH 123 TAKE A LITTLE ONE STEP (EMILY HYE) JDC Dance Center 252 3RD 128 BLAME IT ON THE BOOGIE (SOPHIA JACKSON) JDC Dance Center 252.5 3RD 353 BABY FACE (ASHYTN BARTHELMAS) Class Act Dance 252.5 2ND 221 IT'S A SMALL WORLD (RILEY MARX) JDC Dance Center 262 1ST 356 BORN TO ENTERTAIN (MACIE KUNATH) Class Act Dance 262.5 Solo Intermediate ~ Junior PLACEMENT ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE STUDIO NAME SCORE 10TH 235 MISS INVISIBLE (ARIANNA BENNETT) Class Act Dance 251.5 PARDON MY SOUTHERN ACCENT (ALYSON 9TH 138 JDC Dance Center 252.5 O'CONNOR) Art In Motion Dance 8TH 394 LANDSLIDE (MORGAN HANNAFIN) 253 Academy 7TH 146 UNSTEADY (GRACE CERNIGLIA) The King's Dancers 253.5 Premier Dance Performing 6TH 320 WAKE ME UP (PAYTEN BRETON) 254 Arts Center 5TH 93 MR. PINSTRIPE SUIT (MESKILL AMELIA) Class Act Dance 256 The Isabelle School of 4TH 135 WALKING PAPERS (EMILY MARX) 258.5 Dance Premier Dance Performing 3RD 100 SHOWOFF (KEEGAN ROGERS) 260.5 Arts Center Premier Dance Performing 2ND -

Queer Identities and Glee

IDENTITY AND SOLIDARITY IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES: QUEER IDENITIES AND GLEE Katie M. Buckley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music August 2014 Committee: Katherine Meizel, Advisor Kara Attrep Megan Rancier © 2014 Katie Buckley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine Meizel, Advisor Glee, a popular FOX television show that began airing in 2009, has continuously pushed the limits of what is acceptable on American television. This musical comedy, focusing on a high school glee club, incorporates numerous stereotypes and real-world teenage struggles. This thesis focuses on the queer characteristics of four female personalities: Santana, Brittany, Coach Beiste, and Coach Sue. I investigate how their musical performances are producing a constructive form of mass media by challenging hegemonic femininity through camp and by producing relatable queer female role models. In addition, I take an ethnographic approach by examining online fan blogs from the host site Tumblr. By reading the blogs as a digital archive and interviewing the bloggers, I show the positive and negative effects of an online community and the impact this show has had on queer girls, allies, and their worldviews. iv This work is dedicated to any queer human being who ever felt alone as a teenager. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my greatest thanks to my teacher and advisor, Dr. Meizel, for all of her support through the writing of this thesis and for always asking the right questions to keep me thinking. I would also like to thank Dr.