Assessment Crite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part Three Summer

"What?" "Fine! I'll go!" he yelled, not loudly. "Just stop talking about it already. Can I please read my book now?" "Fine!" I answered. Turning to leave his room, I thought of something. "Did Miranda say anything else about me?" He looked up from the comic book and looked right into my eyes. "She said to tell you she misses you. Quote unquote." I nodded. "Thanks," I said casually, too embarrassed to let him see how happy that made me feel. Part Three Summer You are beautiful no matter what they say Words can't bring you down You are beautiful in every single way Yes, words can't bring you down —Christina Aguilera, "Beautiful" Weird Kids Some kids have actually come out and asked me why I hang out with "the freak" so much. These are kids that don't even know him well. If they knew him, they wouldn't call him that. "Because he's a nice kid!" I always answer. "And don't call him that." "You're a saint, Summer," Ximena Chin said to me the other day. "I couldn't do what you're doing." "It's not a big deal," I answered her truthfully. "Did Mr. Tushman ask you to be friends with him?" Charlotte Cody asked. "No. I'm friends with him because I want to be friends with him," I answered. Who knew that my sitting with August Pullman at lunch would be such a big deal? People acted like it was the strangest thing in the world. It's weird how weird kids can be. -

Merry Christmas! Wednesday, December 26: 9:15-11 Am Women’S Study Group NO Adoration NO F.F.C for Jr

St. Anthony Catholic Church Church 115 N. 25 Mile Ave. | Hereford, Texas 79045 Parish Office:114 Sunset Drive 364-6150 School Office: 120 W. Park Ave. Phone 364-1952. Parish website http://stanthonyscatholicparish.com/ In case of an emergency email: [email protected] or 806-570-5706 PARISH PASTOR — Rev. Fr. Anthony Neusch DIOCESE of AMARILLO — Bishop Patrick Zurek Sign up for R.C.I.A and Small Groups Adult Faith Formation email: [email protected] or call 364-6150 or 364-7626 Bulletin Editor Jasmin Enriquez email: [email protected] bulletin deadline is noon WEDNESDAY. Parish Office Hours: Church Announcements: Mon. 10am– 12pm, 1pm-5pm. Sunday, December 23: Tue. & Thur. 9am-12:30pm, 1pm-5pm. NO RCIA Wed. 9am-12pm, 1pm—5pm. NO Elementary F.F.C NO Holy Hour Fri. 9 am—12 pm, 1 pm—4 pm Monday, December 24: 7 pm Christmas Eve Mass School Announcement. Tuesday, December 25: Sch. Number: (806) 364-1952 Midnight Mass 10 am Christmas Day Mass NO Adoration Merry Christmas! Wednesday, December 26: 9:15-11 am Women’s Study Group NO Adoration NO F.F.C for Jr. High and High school Thursday, December 27: Church office closed, open by appointment only Friday, December 28: Church office closed, open by appointment only 8:15 am School Mass NO book study Saturday, December 29: 1 pm Walk the Boundaries with Fr. Tony Sunday, December 30: NO Elementary F.F.C NO RCIA Fourth Sunday of Advent December 23, 2018 MEMORIES AND DREAMS Throughout our lives, we retain the language and habits of our native region and family of origin. -

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 14 May 9, 2020 9:30PM (EST)

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 14 May 9, 2020 9:30PM (EST) Introduction 1. Question and Answer Session (15 minutes) 2. President’s Report (5 minutes) New Business 1. Wintercession Presentation: Judy Jarvis (25 minutes) 2. Honor Committee Member Confirmations: Christian Potter (5 minutes) 3. Committee on Discipline Member Confirmations: Christian Potter (5 minutes) 4. RRR Referendum Position Paper: Andres Larrieu and Allen Liu (15 minutes) 5. CPUC Meeting Recap: Sarah Lee and Allen Liu (10 minutes) Honor Committee Re-Appointment Bios: Michael Wang ’21: The Honor Committee is excited to reappoint Michael Wang ’21, a junior from Carmel, Indiana who is concentrating in Math. On campus, he is involved with Army ROTC and is a Wilson PAA. Michael wants to continue serving on the Committee because he believes that the next few years of Committee work as we set new precedent and work through the challenges of reform are very important. He also believes it is important that the committee have more experienced members who can help guide the newer members. Samuel Fendler ‘21: The Honor Committee is excited to reappoint Samuel Fendler ’21. Samuel is a junior from New Jersey who is concentrating in Politics. On campus, he has been involved with the Mock Trial Team and the Princeton Student Veteran Group, where he currently holds the position of President. After graduating high school in 2011, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, where he served on Active Duty for five years as an Infantry Rifleman in Afghanistan, Romania, Norway, Finland, and Serbia, among other countries. He spent his final year as a Warfighting Instructor at The Basic School in Quantico, VA. -

A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: the Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2017 A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support Stephanie J. Begun University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Begun, Stephanie J., "A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1293. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1293 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support ___________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Social Work University of Denver ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________ by Stephanie J. Begun June 2017 Advisor: Kimberly Bender, Ph.D., M.S.W. ©Copyright by Stephanie J. Begun 2017 All Rights Reserved Author: Stephanie J. Begun Title: A Mixed Methods Examination of Pregnancy Attitudes and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless Youth: The Role of Social Network Norms and Social Support Advisor: Kimberly Bender, Ph.D., M.S.W. -

MEN's Glee CLUB Giving the Function

WILLAMETTE-C. P. S. --- STADIUM, SATURDAY, NOV. 3, 10 O'CLOCK THE TRAIL OFF ICIAL RUBLICATION OF THE ASSOCIATED STUDENTS OF THE COLLEGE OF PUGET SOUND VOLUME-------------------------------- II ----------------------- TACOMA, WASHINGTON, W.EDNESDAY, OCTOBER 31,--------------------- 1923 ------------------------------NUMBER 7. KNIGHTS OF THE LOG MOST IlYIPORTANT GAMES LOGGERS liOLD HUSKIES TO SCORE INITIATE PLEDGES FOR ,C. P . S. COMING TO COACH MacNEAL Between ha lves at the fooball game The most importa nt game!'> of. the OF 24~0 IN SATURDAY'S BIG GANIE Saturday, the Knights of the Log With the wonderful showing made year a1·e coming this week and n ext by the football team lnst Satmday initiated their 14 freshman pledges. week. The game Saturdr.y will be and thE' praise given to the team, The ceremony w::ts perf ot·med on the in the Stadium a gains •. Will::u:wtte F ig hting ngainst one of the great- line to punt. The pass from center center of the fif.::l'd. The Knights were should go due tribute to Coach R. University. est football machines in the West, was 1ow, and be:fo1·e he could 1·ecover assisted by the Ladies of the S,plin- W. McNeal. With but enough men the lighter, less experienced Logger s the ball it had rolled across the goal ter. They have a !'. !~; t team weighing to make our team, McNeal turned of the College of Puget Sound held line where Hall of the Huskies fell When the teams le.ft the field af- about the san,c as our log·gcrs. -

Joy Comes in the Morning the Funeral of My Daughter-In-Law

Messages of Hope and Peace With a Personal Touch by Paul W. Powell Published by Texas Baptist Leadership Center, Inc. Baptist General Convention of Texas Dedicated to C.W. Beard Paul Chance Elane Gabbert Noble Hurley Frank Marshall Ben Murphy Jerry Parker Tommy Young and all members of Floyd’s Faithful Sunday School Class Good and generous people who love all pastors and whose help and encouragement has enriched my life. 3 Table of Contents 1. Joy Comes In The Morning The Funeral of My Daughter-in-law .................................. 9 2. A Great Man Has Fallen The Funeral of My Boyhood Pastor................................. 17 3. Living Wisely The Funeral of One Who Died Suddenly ........................ 25 4. Learning Life’s Greatest Lessons The Funeral of a Dedicated Deacon ................................ 33 5. What Is Your Life? The Funeral of An Old Friend.......................................... 39 6. A Time For All Things The Funeral of a Faithful Steward ................................... 45 7. A Woman to Remember The Funeral of a Community Servant .............................. 51 8. A Teacher Sent From God The Funeral of a Good Teacher ....................................... 57 9. Happy, Healthy and at Home The Funeral of Someone With An Extended Illness ........ 63 10. The Faith That Sustains The Funeral of a Great Woman ........................................ 67 11. Set Your House In Order The Funeral of a Non Christian ....................................... 73 12. A Balm That Heals A Christmas Memorial Service....................................... -

Testing Darwin's Hypothesis About The

vol. 193, no. 2 the american naturalist february 2019 Natural History Note Testing Darwin’s Hypothesis about the Wonderful Venus Flytrap: Marginal Spikes Form a “Horrid q1 Prison” for Moderate-Sized Insect Prey Alexander L. Davis,1 Matthew H. Babb,1 Matthew C. Lowe,1 Adam T. Yeh,1 Brandon T. Lee,1 and Christopher H. Martin1,2,* 1. Department of Biology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599; 2. Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 Submitted May 8, 2018; Accepted September 24, 2018; Electronically published Month XX, 2018 Dryad data: https://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.h8401kn. abstract: Botanical carnivory is a novel feeding strategy associated providing new ecological opportunities (Wainwright et al. with numerous physiological and morphological adaptations. How- 2012; Maia et al. 2013; Martin and Wainwright 2013; Stroud ever, the benefits of these novel carnivorous traits are rarely tested. and Losos 2016). Despite the importance of these traits, our We used field observations, lab experiments, and a seminatural ex- understanding of the adaptive value of novel structures is of- periment to test prey capture function of the marginal spikes on snap ten assumed and rarely directly tested. Frequently, this is be- traps of the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula). Our field and labora- cause it is difficult or impossible to manipulate the trait with- fi tory results suggested inef cient capture success: fewer than one in four out impairing organismal function in an unintended way; prey encounters led to prey capture. Removing the marginal spikes de- creased the rate of prey capture success for moderate-sized cricket prey however, many carnivorous plant traits do not present this by 90%, but this effect disappeared for larger prey. -

The Piano Duet Play-Along Series Gives You the • I Dreamed a Dream • in My Life • on My Own • Stars

1. Piano Favorites 13. Movie Hits 9 great duets: Candle in the Wind • Chopsticks • Don’t 8 film favorites: Theme from E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial) Know Why • Edelweiss • Goodbye Yellow Brick Road • • Forrest Gump – Main Title (Feather Theme) • The Heart and Soul • Let It Be • Linus and Lucy • Your Song. Godfather (Love Theme) • The John Dunbar Theme • Moon 00290546 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 River • Romeo and Juliet (Love Theme) • Theme from Schindler’s List • Somewhere, My Love. 2. Movie Favorites 00290560 Book/CD Pack ...........................$14.95 8 classics: Chariots of Fire • The Entertainer • Theme from Jurassic Park • My Father’s Favorite • My Heart Will Go 14. Les Misérables On (Love Theme from Titanic) • Somewhere in Time • 8 great songs from the musical: Bring Him Home • Castle on Somewhere, My Love • Star Trek® the Motion Picture. a Cloud • Do You Hear the People Sing? • A Heart Full of Love The Piano Duet Play-Along series gives you the • I Dreamed a Dream • In My Life • On My Own • Stars. flexibility to rehearse or perform piano duets 00290547 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 00290561 Book/CD Pack ...........................$16.95 anytime, anywhere! Play these delightful tunes 3. Broadway for Two 10 songs from the stage: Any Dream Will Do • Blue Skies 15. God Bless America® & Other with a partner, or use the accompanying CDs • Cabaret • Climb Ev’ry Mountain • If I Loved You • Okla- to play along with either the Secondo or Primo Songs for a Better Nation homa • Ol’ Man River • On My Own • There’s No Business 8 patriotic duets: America, the Beautiful • Anchors part on your own. -

Certificate of Analysis

Kaycha Labs Glee 7,000 MG Broad Spectrum Tincture N/A Matrix: Derivative 4131 SW 47th AVENUE SUITE 1408 Sample:DA00416007-007 Harvest/Lot ID: N/A Certificate Seed to Sale #N/A Batch Date :N/A Batch#: GBS700004142020 Sample Size Received: 4 ml of Analysis Retail Product Size: 30 ml Ordered : 04/14/20 Sampled : 04/14/20 Completed: 04/22/20 Expires: 04/22/21 Sampling Method: SOP Client Method Apr 22, 2020 | Glee PASSED 10555 W Donges Court Milwaukee Wisconsin, United States 53224 Page 1 of 1 PRODUCT IMAGE SAFETY RESULTS MISC. Pesticides Heavy Metals Microbials Mycotoxins Residuals Filth Water Activity Moisture Terpenes NOT TESTED NOT TESTED NOT TESTED NOT TESTED Solvents NOT TESTED NOT TESTED NOT TESTED NOT TESTED NOT TESTED CANNABINOID RESULTS Total THC Total CBD Total Cannabinoids 0.000% 24.898% 26.076% CBC CBGA CBG THCV D8-THC CBDV CBN CBDA CBD D9-THC THCA 24.898 ND ND 1.178% ND ND ND ND ND % ND ND 11.780 248.980 ND ND mg/g ND ND ND ND ND mg/g ND ND LOD 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.0001 0.0001 0.001 % % % % % % % % % % % Cannabinoid Profile Test Analyzed by Weight Extraction date : Extracted By : 450 0.1065g NA NA Analysis Method -SOP.T.40.020, SOP.T.30.050 Reviewed On - 04/22/20 15:36:44 Analytical Batch -DA011837POT Instrument Used : DA-LC-003 Batch Date : 04/21/20 11:36:57 Reagent Dilution Consums. ID 042120.R21 400 042120.R20 Full spectrum cannabinoid analysis utilizing High Performance Liquid Chromatography with UV detection (HPLC-UV). -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

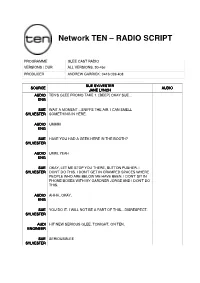

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

Asians & Pacific Islanders Across 1300 Popular Films (2021)

The Prevalence and Portrayal of Asian and Pacific Islanders across 1,300 Popular Films Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen, Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Marc Choueiti, Kevin Yao & Dana Dinh with assistance from Connie Deng Wendy Liu Erin Ewalt Annaliese Schauer Stacy Gunarian Seeret Singh Eddie Jang Annie Nguyen Chanel Kaleo Brandon Tam Gloria Lee Grace Zhu May 2021 ASIANS & PACIFIC ISLANDERS ACROSS , POPULAR FILMS DR. NANCY WANG YUEN, DR. STACY L. SMITH & ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE @NancyWangYuen @Inclusionists API CHARACTERS ARE ABSENT IN POPULAR FILMS API speaking characters across 1,300 top movies, 2007-2019, in percentages 9.6 Percentage of 8.4 API characters overall 5.9% 7.5 7.2 5.6 5.8 5.1 5.2 5.1 4.9 4.9 4.7 Ratio of API males to API females 3.5 1.7 : 1 Total number of speaking characters 51,159 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ A total of 3,034 API speaking characters appeared across 1,300 films API LEADS/CO LEADS ARE RARE IN FILM Of the 1,300 top films from 2007-2019... And of those 44 films*... Films had an Asian lead/co lead Films Depicted an API Lead 29 or Co Lead 44 Films had a Native Hawaiian/Pacific 21 Islander lead/co lead *Excludes films w/ensemble leads OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS WITH API WITH API WITH API WITH API LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS 6 0 0 14 WERE WERE WOMEN WERE WERE GIRLS/WOMEN 40+YEARS OF AGE LGBTQ DWAYNE JOHNSON © ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE TOP FILMS CONSISTENTLY LACK API LEADS/CO LEADS Of the individual lead/co leads across 1,300 top-grossing films..