Dziga Vertov, the First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E

2020 ВЕСТНИК САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Т. 10. Вып. 4 ИСКУССТВОВЕДЕНИЕ КИНО UDC 791.2 Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E. A. Artemeva Mari State University, 1, Lenina pl., Yoshkar-Ola, 424000, Russian Federation For citation: Artemeva, Ekaterina. “Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo”. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 10, no. 4 (2020): 560–570. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu15.2020.402 The article is an attempt to discuss Dziga Vertov’s influence on French filmmakers, in -par ticular on Jean Vigo. This influence may have resulted from Vertov’s younger brother, Boris Kaufman, who worked in France in the 1920s — 1930s and was the cinematographer for all of Vigo’s films. This brother-brother relationship contributed to an important circulation of avant-garde ideas, cutting-edge cinematic techniques, and material objects across Europe. The brothers were in touch primarily by correspondence. According to Boris Kaufman, dur- ing his early career in France, he received instructions from his more experienced brothers, Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman, who remained in the Soviet Union. In addition, Vertov intended to make his younger brother become a French kinok. Also, À propos de Nice, Vigo’s and Kaufman’s first and most “vertovian” film, was shot with the movable hand camera Kina- mo sent by Vertov to his brother. As a result, this French “symphony of a Metropolis” as well as other films by Vigo may contain references to Dziga Vertov’s and Mikhail Kaufman’sThe Man with a Movie Camera based on framing and editing. In this perspective, the research deals with transnational film circulations appealing to the example of the impact of Russian avant-garde cinema on Jean Vigo’s films. -

Soviet Cinema

Soviet Cinema: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942 Where to Order BRILL AND P.O. Box 9000 2300 PA Leiden The Netherlands RUSSIA T +31 (0)71-53 53 500 F +31 (0)71-53 17 532 BRILL IN 153 Milk Street, Sixth Floor Boston, MA 02109 USA T 1-617-263-2323 CULTURE F 1-617-263-2324 For pricing information, please contact [email protected] MASS www.brill.nl www.idc.nl “SOVIET CINemA: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942” collections of unique material about various continues the new IDC series Mass Culture and forms of popular culture and entertainment ENTERTAINMENT Entertainment in Russia. This series comprises industry in Tsarist and Soviet Russia. The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment in Russia The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment diachronic dimension. It includes the highly in Russia comprises collections of extremely successful collection Gazety-Kopeiki, as well rare, and often unique, materials that as lifestyle magazines and children’s journals offer a stunning insight into the dynamics from various periods. The fifth sub-series of cultural and daily life in Imperial and – “Everyday Life” – focuses on the hardship Soviet Russia. The series is organized along of life under Stalin and his somewhat more six thematic lines that together cover the liberal successors. Finally, the sixth – “High full spectrum of nineteenth- and twentieth Culture/Art” – provides an exhaustive century Russian culture, ranging from the overview of the historic avant-garde in Russia, penny press and high-brow art journals Ukraine, and Central Europe, which despite in pre-Revolutionary Russia, to children’s its elitist nature pretended to cater to a mass magazines and publications on constructivist audience. -

Aleksandr Rodchenko. Model Workers' Club, Soviet Pavilion at The

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00147/1754067/octo_a_00147.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Aleksandr Rodchenko. Model Workers’ Club, Soviet pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels in Paris. 1925. © Estate of Alexander Rodchenko/RAO, Moscow/VAGA, New York. Labor Demonstrations: Aleksei Gan’s Island of the Young Pioneers , Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Eye , and the Rationalization of Artistic Labor* Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00147/1754067/octo_a_00147.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 KRISTIN ROMBERG Of Russian Constructivism’s manifold demonstration pieces, the model workers’ club that Aleksandr Rodchenko exhibited in Paris in 1925 is one of the best. Its economy of materials and transparent structural logic exemplify Constructivism’s rationalist bid for a socialist aesthetics, while its function as a club models the ideal of enlightened recreation as the partner to unalienated labor. 1 Visible in the well-known photograph of the club are posters for the two films that are the subject of this essay. Both were conceived as demonstration pieces in their own right. The poster in the center, also designed by Rodchenko, is for Dziga Vertov’s first feature-length film, Kino-Eye . The one to the right, with the pared-down typographic layout, advertises Aleksei Gan’s Island of the Young Pioneers .2 Both films were made in 1924 and featured the Young Pioneers, the Soviet youth organization for children ages ten to fifteen founded in 1922 on the model of the Boy Scouts. Both were produced as examples of a new approach to filmmaking called “the demonstration of everyday life.” But while Kino-Eye has gone on to be celebrated as the closest thing to Constructivism in cinema, 3 Island has only been mentioned in passing, and even then as a complete disaster. -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

Soviet Diy: Samizdat & Hand-Made Books

www.bookvica.com SOVIET DIY: SAMIZDAT & HAND-MADE BOOKS. RECENT ACQUSITIONS 2017 F O R E W O R D Dear friends, Please welcome our latest venture - the October catalogue of 2017. We are always in search for interesting cultural topics to shine the light on, and this time we decided to put together a collection of books made by amateurs and readers to spread the texts that they believed should have been distributed. Soviet State put a great pressure on its citizens, censoring the unwanted content and blocking the books that mattered to people. But in the meantime the process of alternative distribution of the texts was going on. We gathered some of samizdat books, manuscripts, hand-made books to show what was created by ordinary people. Sex manuals, rock’n’roll encyclopedias, cocktail guides, banned literature and unpublished stories by children - all that was hard to find in a Soviet bookshop and hence it makes an interesting reading. Along with this selection you can review our latest acquisitions: we continue to explore the world of pre-WWII architecture with a selection of books containing important theory, unfinished projects and analysis of classic buildings of its time like Lenin’s mausoleum. Two other categories are dedicated to art exhibitions catalogues and books on cinema in 1920s. We are adding one more experimental section this time: the books in the languages of national minorities of USSR. In 1930s the language reforms were going on across the union and as a result some books were created, sometimes in scripts that today no-one is able to read, because they existed only for a short period of time. -

Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism*

Across One Sixth of the World: Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism* OKSANA SARKISOVA The films of Dziga Vertov display a persistent fascination with travel. Movement across vast spaces is perhaps the most recurrent motif in his oeuvre, and the cine-race [kino-probeg]—a genre developed by Vertov’s group of filmmak- ers, the Kinoks 1—stands as an encompassing metaphor for Vertov’s own work. His cinematographic journeys transported viewers to the most remote as well as to the most advanced sites of the Soviet universe, creating a heterogeneous cine-world stretching from the desert to the icy tundra and featuring customs, costumes, and cultural practices unfamiliar to most of his audience. Vertov’s personal travelogue began when he moved from his native Bialystok2 in the ex–Pale of Settlement to Petrograd and later to Moscow, from where, hav- ing embarked on a career in filmmaking, he proceeded to the numerous sites of the Civil War. Recalling his first steps in cinema, Vertov described a complex itin- erary that included Rostov, Chuguev, the Lugansk suburbs, and even the Astrakhan steppes.3 In the early 1920s, when the film distribution network was severely restricted by the Civil War and uneven nationalization, traveling and film- making were inseparable. Along with other filmmakers, he used an improvised * This article is part of my broader research “Envisioned Communities: Representations of Nationalities in Non-Fiction Cinema in Soviet Russia, 1923–1935” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Central European University, 2004). I would like to warmly thank my teachers and friends for sharing their knowledge and enthusiasm throughout this long journey. -

CLUB of the NEW SOCIAL TYPE Yixin Zhou Arch 646: History And

SOCIALISM AND REPRESENTATIONAL UTOPIA: CLUB OF THE NEW SOCIAL TYPE Yixin Zhou Arch 646: History and Theory of Architecture III Research Paper Dec. 14, 2016 Zhou !2 Abstract This paper studies the “Club of the New Social Type” by Ivan Leonidov in 1928, a research study project for a prototype of workers’ club. As a project in the early stage of Leonidov’s career, it embodies various sources of influences upon the architect from Suprematism to Constructivism. The extremity in the abstraction of forms, specific consideration of programs and the social ambition of Soviet avant-garde present themselves in three different dimensions. Therefore, the paper aims to analyze the relationships of the three aspects to investigate the motivation and thinking in the process of translating a brief into a project. Through the close reading of the drawings against the historical context, the paper characterizes the project as socialism and representational utopia. The first part of the paper would discuss the socialist aspect of the “Club of the New Social Type”. I will argue that the project demonstrates Leonidov’s interest in collective rather than individual not only spatially, but also in term of mass behavior and program concern. In the second part, the arguments will be organized on the representation technique in the drawings which renders the project in a utopian aesthetic. It reveals the ambition that the club would function as a prototype for the society and be adopted universally. Throughout the paper, the project would be constantly situated in the genealogy of architectural history for a comparison of ideas. -

Film and Literary Modernism

Film and Literary Modernism Film and Literary Modernism Edited by Robert P. McParland Film and Literary Modernism, Edited by Robert P. McParland This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Robert P. McParland and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4450-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4450-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 I. City Symphony Films A City Symphony: Urban Aesthetics and the Poetics of Modernism on Screen ................................................................................................... 12 Meyrav Koren-Kuik The Experimental Modernism in the City Symphony Film Genre............ 20 Cecilia Mouat Reconsidering Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta..................... 27 Kristen Oehlrich II. Perspectives To See is to Know: Avant-Garde Film as Modernist Text ........................ 42 William Verrone Tomato’s Another Day: The Improbable Subversion of James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber .................................................................. -

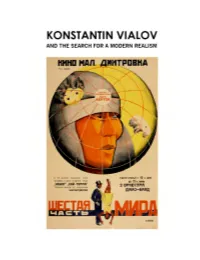

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Dziga Vertov's the Man with the Movie Camera

Contact: Josh Morrison, Operations Manager, [email protected] FLICKER ALLEY PRESENTS DZIGA VERTOV’S THE MAN WITH THE MOVIE CAMERA Flicker Alley, in association with Lobster Films, the Blackhawk Films® Collection, the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, and EYE Film Institute, brings the extraordinary restoration of Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera to its North American premiere. Flicker Alley, Lobster Films, and the Blackhawk Films® Collection are proud to present the pristine restoration of a cinematic masterpiece from one of the pioneers of Soviet film. Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera and Other Newly-Restored Works Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera / 1929 / Directed by Dziga Vertov / 68 minutes / U.S.S.R. / Produced by VUFKU, Goskino, Ukrainfilm, and Mezhrabpom "I am an eye. A mechanical eye. I am the machine that reveals the world to you as only the machine can see it." - Dziga Vertov ("Kino-Eye") These words, written in 1923 (only a year after Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North was released) reflect the Soviet pioneer's developing approach to cinema as an art form that shuns traditional or Western narrative in favor of images from real life. They lay the foundation for what would become the crux of Vertov's revolutionary, anti-bourgeois aesthetic wherein the camera is an extension of the human eye, capturing "the chaos of visual phenomena filling the universe." Over the next decade-and-a-half, Vertov would devote his life to the construction and organization of these raw images, his apotheosis being the landmark 1929 film The Man with the Movie Camera. -

INTRODUCTION Embedded Aesthetics and Situated History

INTRODUCTION Embedded Aesthetics and Situated History YEAR BEFORE JOINING ALEKSEI GAN in founding the Working Group of Constructivists, Varvara Stepanova A noted a peculiar orientation in her future colleague. In March 1920, she recorded in her diary with apparent bemuse- ment, “Gan considers agitation as important as creating a work.”1 As cofounder of the working group, the framer of their theoretical program, and the only person involved in nearly all of constructivism’s manifestations across disciplines—including mass festivals, the “laboratory period,” theater, industrial design, print, cinema, and architecture—Gan was ubiquitous within the movement, even arguably its central figure, but his position was also idiosyncratic. Never a professional artist per se, he worked primarily as a political organizer. Stepanova’s comment percep- tively points to the fundamental insight Gan brought to the constructivist project from that experience: within a society organized around mass production and public spaces, part of the construction of any object was the construction of a broad public for it. From Gan’s standpoint, the “work of art” was less an object 1 58905int.indd 1 2018-09-13 10:24 AM than a labor process through which new publics were constituted and new modes of sociality cultivated. This book presents a new understanding of Russian constructivism by retelling its story from that perspective, with Gan as its central protagonist. At times that tale will feel heroic, but equally oftentimes tragic. Mostly it will be a gritty on-the-ground story about bumbling through the trials and errors of working to shape an evolving political field from a position deeply embedded within it.