Aleksandr Rodchenko. Model Workers' Club, Soviet Pavilion at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Dziga Vertov, the First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1

Dziga Vertov, The First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1 Devin Fore Princeton University Abstract We are told that the mechanization of production has dire effects on the functionality of language as well as human capacities for symbolic communication in general. This expropriation of language by the machine results in the deterioration of the traditional political public sphere, which once privileged language as the exclusive medium of intersubjectivity and agency. The essay argues that the work of the Soviet media artist Dziga Vertov, especially his 1931 “film-thing” En- thusiasm, sought to redress the antagonism between technology and politics faced by modern industrial societies. Vertov’s public sphere was one that did not privilege language and abstract discourse, but that incorporated all manner of material objects as means of commu- nication. As Vertov instructed, the public sphere must move beyond its linguistic bias to embrace industrial commodities as communica- tive social media. 1. This article is excerpted from a longer paper that examines Dziga Vertov’s work with television, but that cannot appear here in its entirety because of exigencies of space. Postponing the discussion of early television’s position within the Soviet media land- scape for a later context, the present article limits itself to the exposition of two argu- ments: the first section addresses the fate of political discourse within modern regimes of industrial production; then, through an analysis of one passage from Vertov’s film Enthusiasm (1931), the second section considers Vertov’s strategies for forging new modes of political agency within the sphere of technical production. Configurations, 2010, 18:363–382 © 2011 by The Johns Hopkins University Press and the Society for Literature and Science. -

CLUB of the NEW SOCIAL TYPE Yixin Zhou Arch 646: History And

SOCIALISM AND REPRESENTATIONAL UTOPIA: CLUB OF THE NEW SOCIAL TYPE Yixin Zhou Arch 646: History and Theory of Architecture III Research Paper Dec. 14, 2016 Zhou !2 Abstract This paper studies the “Club of the New Social Type” by Ivan Leonidov in 1928, a research study project for a prototype of workers’ club. As a project in the early stage of Leonidov’s career, it embodies various sources of influences upon the architect from Suprematism to Constructivism. The extremity in the abstraction of forms, specific consideration of programs and the social ambition of Soviet avant-garde present themselves in three different dimensions. Therefore, the paper aims to analyze the relationships of the three aspects to investigate the motivation and thinking in the process of translating a brief into a project. Through the close reading of the drawings against the historical context, the paper characterizes the project as socialism and representational utopia. The first part of the paper would discuss the socialist aspect of the “Club of the New Social Type”. I will argue that the project demonstrates Leonidov’s interest in collective rather than individual not only spatially, but also in term of mass behavior and program concern. In the second part, the arguments will be organized on the representation technique in the drawings which renders the project in a utopian aesthetic. It reveals the ambition that the club would function as a prototype for the society and be adopted universally. Throughout the paper, the project would be constantly situated in the genealogy of architectural history for a comparison of ideas. -

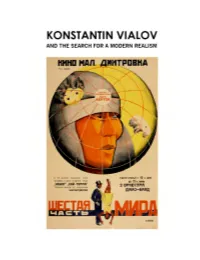

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

INTRODUCTION Embedded Aesthetics and Situated History

INTRODUCTION Embedded Aesthetics and Situated History YEAR BEFORE JOINING ALEKSEI GAN in founding the Working Group of Constructivists, Varvara Stepanova A noted a peculiar orientation in her future colleague. In March 1920, she recorded in her diary with apparent bemuse- ment, “Gan considers agitation as important as creating a work.”1 As cofounder of the working group, the framer of their theoretical program, and the only person involved in nearly all of constructivism’s manifestations across disciplines—including mass festivals, the “laboratory period,” theater, industrial design, print, cinema, and architecture—Gan was ubiquitous within the movement, even arguably its central figure, but his position was also idiosyncratic. Never a professional artist per se, he worked primarily as a political organizer. Stepanova’s comment percep- tively points to the fundamental insight Gan brought to the constructivist project from that experience: within a society organized around mass production and public spaces, part of the construction of any object was the construction of a broad public for it. From Gan’s standpoint, the “work of art” was less an object 1 58905int.indd 1 2018-09-13 10:24 AM than a labor process through which new publics were constituted and new modes of sociality cultivated. This book presents a new understanding of Russian constructivism by retelling its story from that perspective, with Gan as its central protagonist. At times that tale will feel heroic, but equally oftentimes tragic. Mostly it will be a gritty on-the-ground story about bumbling through the trials and errors of working to shape an evolving political field from a position deeply embedded within it. -

Cultural Syllabus : Russian Avant-Garde and Radical Modernism : an Introductory Reader

———————————————————— Introduction ———————————————————— THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE AND RADICAL MODERNISM An Introductory Reader Edited by Dennis G. IOFFE and Frederick H. WHITE Boston 2012 — 3 — ——————————— RUSSIAN SUPREMATISM AND CONSTRUCTIVISM ——————————— 1. Kazimir Malevich: His Creative Path1 Evgenii Kovtun (1928-1996) Translated from the Russian by John E. Bowlt Te renewal of art in France dating from the rise of Impressionism extended over several decades, while in Russia this process was consoli- dated within a span of just ten to ffteen years. Malevich’s artistic devel- opment displays the same concentrated process. From the very begin- ning, his art showed distinctive, personal traits: a striking transmission of primal energy, a striving towards a preordained goal, and a veritable obsession with the art of painting. Remembering his youth, Malevich wrote to one of his students: “I worked as a draftsman... as soon as I got of work, I would run to my paints and start on a study straightaway. You grab your stuf and rush of to sketch. Tis feeling for art can attain huge, unbelievable proportions. It can make a man explode.”2 Transrational Realism From the early 1910s onwards, Malevich’s work served as an “experimen- tal polygon” in which he tested and sharpened his new found mastery of the art of painting. His quest involved various trends in art, but although Malevich firted with Cubism and Futurism, his greatest achievements at this time were made in the cycle of paintings he called “Alogism” or “Transrational Realism.” Cow and Violin, Aviator, Englishman in Moscow, Portrait of Ivan Kliun—these works manifest a new method in the spatial organization of the painting, something unknown to the French Cub- ists. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents • Abbreviations & General Notes 2 - 3 • Photographs: Flat Box Index 4 • Flat Box 1- 43 5 - 61 Description of Content • Lever Arch Files Index 62 • Lever Arch File 1- 16 63 - 100 Description of Content • Slide Box 1- 7 101 - 117 Description of Content • Photographs in Index Box 1 - 6 118 - 122 • Index Box Description of Content • Framed Photographs 123 - 124 Description of Content • Other 125 Description of Content • Publications and Articles Box 126 Description of Content Second Accession – June 2008 (additional Catherine Cooke visual material found in UL) • Flat Box 44-56 129-136 Description of Content • Postcard Box 1-6 137-156 Description of Content • Unboxed Items 158 Description of Material Abbreviations & General Notes, 2 Abbreviations & General Notes People MG = MOISEI GINZBURG NAM = MILIUTIN AMR = RODCHENKO FS = FEDOR SHEKHTEL’ AVS = SHCHUSEV VNS = SEMIONOV VET = TATLIN GWC = Gillian Wise CIOBOTARU PE= Peter EISENMANN WW= WALCOT Publications • CA- Современная Архитектура, Sovremennaia Arkhitektura • Kom.Delo – Коммунальное Дело, Kommunal’noe Delo • Tekh. Stroi. Prom- Техника Строительство и Промышленность, Tekhnika Stroitel’stvo i Promyshlennost’ • KomKh- Коммунальное Хозяство, Kommunal’noe Khoziastvo • VKKh- • StrP- Строительная Промышленность, Stroitel’naia Promyshlennost’ • StrM- Строительство Москвы, Stroitel’stvo Moskvy • AJ- The Architect’s Journal • СоРеГор- За Социалистическую Реконструкцию Городов, SoReGor • PSG- Планировка и строительство городов • BD- Building Design • Khan-Mag book- Khan-Magomedov’s -

Photography & Graphic Applications Mobilized by Constructivist

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL REVOLUTION BY DESIGN: PHOTOGRAPHY & GRAPHIC APPLICATIONS MOBILIZED BY CONSTRUCTIVIST ALEKSANDR RODCHENKO IN THE 1920S SOVIET JOURNAL "NOVY LEF" MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDE DES ARTS PAR RENÉE-CLAUDE LANDRY JUIN 2013 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques · Ayertfssement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le( respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire. at de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles 5 up~rlaurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que <<conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études da cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une llc~nce non exclusive d'utilisation et da . publication de la totalité ou d'une partie Importante da [son] travail de recherche pour dea fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur) autorisa l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre dea copies de. [son] travail de recherche à dea fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y comprtsl'lntemel Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entrainent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur) conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il} possède un exemplaire.~ TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ii REMERCIEMENTS iii LIST OF FIGURES iv RESUME -

Celebrating Suprematism: New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir

Celebrating Suprematism Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks (The Johns Hopkins University) Christina Lodder (University of Kent) Volume 22 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Celebrating Suprematism New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir Malevich Edited by Christina Lodder Cover illustration: Installation photograph of Kazimir Malevich’s display of Suprematist Paintings at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, 0.10 (Zero-Ten), in Petrograd, 19 December 1915 – 19 January 1916. Photograph private collection. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lodder, Christina, 1948- editor. Title: Celebrating Suprematism : new approaches to the art of Kazimir Malevich / edited by Christina Lodder. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2019] | Series: Russian history and culture, ISSN1877-7791 ; Volume 22 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN2018037205 (print) | LCCN2018046303 (ebook) | ISBN9789004384989 (E-book) | ISBN 9789004384873 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Malevich, Kazimir Severinovich, 1878-1935–Criticism and interpretation. | Suprematism in art. | UNOVIS (Group) Classification: LCCN6999.M34 (ebook) | LCCN6999.M34C452019 (print) | DDC 700.92–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037205 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN1877-7791 ISBN 978-90-04-38487-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-38498-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

16-Mm Film Strips from Hans Richter's Unfin- Ished Film Based on Kazimir

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00131/1753684/octo_a_00131.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 16-mm film strips from Hans Richter’s unfin - ished film based on Kazimir Malevich’s 1927 scenario. c. 1970. © Hans Richter Estate. Malevich and Richter: An Indeterminate Encounter Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00131/1753684/octo_a_00131.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 TIMOTHY O. BENSON AND ALEKSANDRA SHATSKIKH A meeting between Kazimir Malevich and Hans Richter in Berlin in 1927 has led to much speculation about a “close” relationship and artistic collabora - tion between two titans of abstraction to create a film whose realization was tragically prevented by historical circumstances. 1 The primary artifact of this encounter is a scenario by Malevich, now part of the lore of our genesis narra - tive of avant-garde film. Yet nearly everything about this encounter is far more indeterminate, including the historical moment of Malevich’s conception of the film, the date of his execution of the scenario, the degree of communication between the two, and the relationship of the incomplete film that was actually made some forty-four years later to Malevich’s and Richter’s ideas about abstract film. Surviving in 16-mm strips in Richter’s estate and in rushes and work prints at the Getty Research Institute, the film remained incomplete largely because its makers, Richter and his cameraman, Arnold Eagle, could no longer discern for themselves whether the creator was Richter or Malevich (they hoped for the lat - ter). -

Graphic Design Theory: Readings from the Field / Edited by Helen Armstrong

Graphic Desi Gn Theory Readings from the fiEld Edited by Helen Armstrong PrincEton ArcHitEcturAl PrEss nEw York Published by Princeton Architectural Press 37 East Seventh Street New York, New York 10003 For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657. Visit our website at www.papress.com. © 2009 Princeton Architectural Press All rights reserved Printed and bound in China 12 11 10 09 4 3 2 1 First edition No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. This project was produced with editorial support from the Center for Design Thinking, Maryland Institute College of Art. Design Briefs Series Editor: Ellen Lupton Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Sara Bader, Nicola Bednarek, Janet Behning, Becca Casbon, Carina Cha, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Pete Fitzpatrick, Wendy Fuller, Jan Haux, Aileen Kwun, Nancy Eklund Later, Linda Lee, Aaron Lim, Laurie Manfra, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Lauren Nelson Packard, Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press — Kevin C. Lippert, publisher Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graphic design theory: readings from the field / edited by Helen Armstrong. p. cm. — (Design briefs) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56898-772-9 (alk. paper) 1. Graphic arts. 2. Commercial art. I. Armstrong, Helen, 1971– NC997.G673 2008 741.6—dc22 2008021063 2007 Designing Design Kenya Kenya tHE futurE liEs AHEAd of us, but bEHind us tHErE is Also A grEAt h AccumulAtion of HistorY—A rEsourcE for imAginAtion And crEAtivitY. -

Abstraction Beyond Art

THE AESTHETICS OF CENSORSHIP AND THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE: Abstraction Beyond Art Volume One KAMILA KOCIAŁKOWSKA Pembroke College Department of History of Art University of Cambridge November 2019 THIS DISSERTATION IS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PREFACE This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of any other University or similar institution except as specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University of similar institution except as declared in the Preface specified in the text. The dissertation is 78, 682 words in length, including footnotes and list of images, but excluding image captions and bibliography. Cover image: Varvara Stepanova, Risunek dlia tekstil’ (1924) Kamila Kociałkowska Pembroke College 29th November 2019 ABSTRACT This thesis reconsiders the art of the Russian avant-garde by exploring its engagement with, influence from and contribution towards an unconventional area of culture: censorship. Although extensive research has already considered the way artists such as Malevich, Rodchenko and Stepanova blurred the binaries between art and vandalism, construction and deconstruction in their work, this analysis has not yet extended to consider their engagement with institutions of censorship to its full extent.