Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

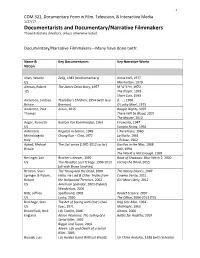

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

From L'atalante to Young Adam Walter C

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Articles Department of Cinema and Photography Spring 2011 A Dreary Life on a Barge: From L'Atalante to Young Adam Walter C. Metz Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cp_articles Recommended Citation Metz, Walter C. "A Dreary Life on a Barge: From L'Atalante to Young Adam." Weber: The Contemporary West 27, No. 2 (Spring 2011): 51-66. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Cinema and Photography at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walter Metz A Dreary Life on a Barge: From L’Atalante to Young Adam Young Adam: The barge amidst the Scottish landscape PRELUDE While surfing around Netflix looking If there is anything further in spirit from for the name of the film in which Ewan L’Atalante—a romantic fairy tale about McGregor played James Joyce—Nora the enduring power of love—it must be (Pat Murphy, 2000)—I stumbled across Young Adam, a bitter tale of an astonish- Young Adam (David Mackenzie, 2003), ingly amoral drifter who kills one woman a film in which the young Obi-Wan plays and uses all of the others he encounters to a man who gets involved in a romantic quaff his ruthless sexual appetite. And yet, triangle aboard a river barge. Immedi- Mackenzie’s film—repeatedly and perhaps ately, I thought of L’Atalante (Jean Vigo, unavoidably—echoes scenes and situa- 1934), the most famous barge movie of tions from L’Atalante. -

Film Studies A-Level Induction Work to Prepare You for September 2021

Film Studies A-Level Induction work to prepare you for September 2021 Email Miss Potts or Mr Howse if you have any questions – [email protected] or [email protected] Component 1: Varieties of film and filmmaking - Exam – 2 ½ Component 2: Global filmmaking perspectives - Exam – 2 ½ hours – 35% hours – 35% Section A: Hollywood 1930-1990 (comparative study) Section A: Global film (two-film study) Group 1: Classical Hollywood 1930- Group 2: New Hollywood (1961- Group 1: European Film Group 2: Outside Europe 1960) 1990) - Life is Beautiful (Benigni, Italy, 1997, - Dil Se (Ratnam, India, 1998, 12) - Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942, U) - Bonnie and Clyde (Penn, 1967, 15) PG) - City of God (Meirelles, Brazil, 2002) - The Lady from Shanghai (Welles, - OFOTCN (Forman, 1975, 15) - Pan’s Labyrinth (Del Toro, Spain, 2006, - House of Flying Daggers (Zhang, China, 1947, PG) - Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979, 15) 2004, 15) - Johnny Guitar (Ray, 1954, PG) 15) - Diving Bell (Schnabel, France 2007, 12) - Timbuktu (Sissako, Mauritania, 2014, - Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958, PG) - Blade Runner (Scott, 1982, 15) - Ida (Pawlikowski, Poland, 2013, 15) 12A) - Some Like It Hot (Wilder, 1959, 12) - Do The Right Thing (Lee, 1989, 15) - Mustang (Erguven, Turkey, 2015, 15) - Wild Tales (Szifron, Argentina, 2014, 15) - Victoria (Schipper, Germany, 2015, 15) - Taxi Tehran (Panahi, Iran, 2015, 12) Section B: American film since 2005 (two-film study) Section B: Documentary film Section C: Film movements – Silent - Sisters in Law (Ayisi, Cameroon, 20015, Group -

Representaciones Realistas De Niños, Adolescentes Y Jóvenes Marginales En El Cine Iberoamericano (1990-2003)

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA, LENGUAS MODERNAS, LÓGICA Y FILOSOFÍA DE LA CIENCIA, TEORÍA DE LA LITERATURA Y LITERATURA COMPARADA PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN HISTORIA DEL CINE Representaciones realistas de niños, adolescentes y jóvenes marginales en el cine iberoamericano (1990-2003) TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: Juan Carlos Vargas Maldonado Director: Dr. Alberto Elena Díaz Madrid, junio de 2008 2 ÍNDICE Introducción 3 1. Las primeras búsquedas “realistas” en el cine 8 1.1 El realismo socialista 11 1.2 El documental etnográfico 13 1.3 El documental social 16 1.4 El realismo poético francés 17 1.5 Dos antecedentes realistas del cine de ficción mexicano y español 19 1.6 El neorrealismo italiano 23 1.7 Ejemplos prototípicos: El Limpiabotas y La tierra tiembla 27 2. Los olvidados: modelo paradigmático sobre los niños, adolescentes y 33 jóvenes marginales 3. La herencia del neorrealismo en las cinematografías venezolana, 42 brasileña, argentina, española, chilena, boliviana y colombiana (1950-1981) 3.1 Venezuela: La escalinata y Soy un delincuente 46 3.2 Brasil: Río 40 grados y Pixote, los olvidados de Dios 54 3.3 Argentina: Tire dié, Crónica de un niño solo y La Raulito 65 3.4 España: Los golfos y Deprisa, deprisa 77 3.5 Chile: Largo viaje y Valparaíso, mi amor 86 3.6 Bolivia: Chuquiago 93 3.7 Colombia: Gamín 97 4. Representaciones realistas 1990-2003 105 4.1 Delincuencia y crimen: Caluga o menta (Chile/España), Lolo (México), 108 Como nacen los ángeles (Brasil) y Ciudad de Dios (Brasil/Francia/Alemania), Pizza, birra, faso (Argentina), Barrio (España/Francia) y Ratas, ratones y rateros (Ecuador/Estados Unidos) 4.2 Sicarios: Sicario (Venezuela) y La virgen de los sicarios 155 (Colombia/España/Francia) 4.3 Niños de la calle: La vendedora de rosas (Colombia), Huelepega, 170 ley de la calle (Venezuela/España), De la calle (México) y El Polaquito (Argentina/España) 5. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

Elizaveta Svilova – Women Film Pioneers Project

4/7/2020 Elizaveta Svilova – Women Film Pioneers Project Elizaveta Svilova Also Known As: Elizaveta Schnitt, Elizaveta Vertova-Svilova, Yelizaveta Ignatevna Svilova, Yelizaveta Svilova Lived: September 5, 1900 - November 11, 1975 Worked as: archivist, assistant director, co-director, director, editor Worked In: Russia, Soviet Union by Eva Molcard A film editor, director, writer, and archivist, Elizaveta Svilova was an intellectual and creative force in early Soviet montage. She is best known for her extensive collaborations with her husband, Dziga Vertov, on seminal early documentary films, and especially for instances when she appeared on camera demonstrating the act of editing itself. The fact that Vertov’s filmic theory and practice focused on montage as the fundamental guiding force of cinema confirms the crucial role Svilova’s groundbreaking experimentation played in early Soviet film and global film history. Her career, which spanned far beyond her collaborations with her husband, significantly advanced the early principles of cinematic montage. Svilova was born Elizaveta Schnitt in Moscow on September 5, 1900, to a railway worker and a housewife. She began working in the cinema industry at age twelve, apprenticing in a film laboratory where she cleaned, sorted, and selected film and negatives (Kaganovsky 2018). This sort of work, seen as akin to domestic chores like sewing, weaving, and other “feminine” activities, was often the domain of women in film industries worldwide. At age fourteen, Svilova was hired as an assistant editor at Pathé’s Moscow studio, where she cut and photo-printed film until 1918. She worked as an editor for Vladimir Gardin while at Pathé, and edited iconic early films such as Vsevolod Meyerhold’s 1915 adaptation of The Picture of Dorian Gray. -

Soviet Cinema

Soviet Cinema: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942 Where to Order BRILL AND P.O. Box 9000 2300 PA Leiden The Netherlands RUSSIA T +31 (0)71-53 53 500 F +31 (0)71-53 17 532 BRILL IN 153 Milk Street, Sixth Floor Boston, MA 02109 USA T 1-617-263-2323 CULTURE F 1-617-263-2324 For pricing information, please contact [email protected] MASS www.brill.nl www.idc.nl “SOVIET CINemA: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942” collections of unique material about various continues the new IDC series Mass Culture and forms of popular culture and entertainment ENTERTAINMENT Entertainment in Russia. This series comprises industry in Tsarist and Soviet Russia. The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment in Russia The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment diachronic dimension. It includes the highly in Russia comprises collections of extremely successful collection Gazety-Kopeiki, as well rare, and often unique, materials that as lifestyle magazines and children’s journals offer a stunning insight into the dynamics from various periods. The fifth sub-series of cultural and daily life in Imperial and – “Everyday Life” – focuses on the hardship Soviet Russia. The series is organized along of life under Stalin and his somewhat more six thematic lines that together cover the liberal successors. Finally, the sixth – “High full spectrum of nineteenth- and twentieth Culture/Art” – provides an exhaustive century Russian culture, ranging from the overview of the historic avant-garde in Russia, penny press and high-brow art journals Ukraine, and Central Europe, which despite in pre-Revolutionary Russia, to children’s its elitist nature pretended to cater to a mass magazines and publications on constructivist audience. -

Hartnett Dissertation

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Recorded Objects: Time-Based Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 A Dissertation Presented by Gerald Hartnett to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University August 2017 Stony Brook University 2017 Copyright by Gerald Hartnett 2017 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Gerald Hartnett We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Andrew V. Uroskie – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Art Jacob Gaboury – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor, Department of Art Brooke Belisle – Third Reader Assistant Professor, Department of Art Noam M. Elcott, Outside Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art History, Columbia University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Recorded Objects: Time-Based, Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 by Gerald Hartnett Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2017 Illuminating experimental, time-based, and technologically reproducible art objects produced between 1954 and 1964 to represent “the real,” this dissertation considers theories of mediation, ascertains vectors of influence between art and the cybernetic and computational sciences, and argues that the key practitioners responded to technological reproducibility in three ways. First of all, writers Guy Debord and William Burroughs reinvented appropriation art practice as a means of critiquing retrograde mass media entertainments and reportage. -

Zéro De Conduite: Jeunes Diables Au Collège (Zero for Conduct)

Quarterly Review of Film and Video ISSN: 1050-9208 (Print) 1543-5326 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gqrf20 Zéro de conduite: Jeunes diables au collège (Zero for Conduct) Maria Pramaggiore To cite this article: Maria Pramaggiore (2010) Zéro de conduite: Jeunes diables au collège (Zero for Conduct), Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 27:5, 413-415, DOI: 10.1080/10509208.2010.495003 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208.2010.495003 Published online: 04 Oct 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 170 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gqrf20 Essays 413 the film has remained to this day, as contemporary German cinema is still awaiting a more systemic effort at rejuvenating what constitutes the lifeblood of any properly functioning film industry: genre cinema. Marco Abel teaches film studies and continental theory in the Department of English at the University of Nebraska and is currently working on his second book, The Berlin School: Toward a Minor Cinema.Hehasa longer essay on Dominik Graf forthcoming in Generic Histories: Genre and its Deviations in German Cinema (ed. Jaimey Fisher). Zero´ de conduite: Jeunes diables au college` (Zero for Conduct) MARIA PRAMAGGIORE Refused a certificate by the French Comite´ national du cinema´ (Film Control Board) on the grounds that its satirical attack on the education system was seditious, Jean Vigo’s Zero´ de Conduite (1933) would not be screened commercially in France until 1945, 11 years after the director’s death from tuberculosis at age 29. -

Dziga Vertov, the First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1

Dziga Vertov, The First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1 Devin Fore Princeton University Abstract We are told that the mechanization of production has dire effects on the functionality of language as well as human capacities for symbolic communication in general. This expropriation of language by the machine results in the deterioration of the traditional political public sphere, which once privileged language as the exclusive medium of intersubjectivity and agency. The essay argues that the work of the Soviet media artist Dziga Vertov, especially his 1931 “film-thing” En- thusiasm, sought to redress the antagonism between technology and politics faced by modern industrial societies. Vertov’s public sphere was one that did not privilege language and abstract discourse, but that incorporated all manner of material objects as means of commu- nication. As Vertov instructed, the public sphere must move beyond its linguistic bias to embrace industrial commodities as communica- tive social media. 1. This article is excerpted from a longer paper that examines Dziga Vertov’s work with television, but that cannot appear here in its entirety because of exigencies of space. Postponing the discussion of early television’s position within the Soviet media land- scape for a later context, the present article limits itself to the exposition of two argu- ments: the first section addresses the fate of political discourse within modern regimes of industrial production; then, through an analysis of one passage from Vertov’s film Enthusiasm (1931), the second section considers Vertov’s strategies for forging new modes of political agency within the sphere of technical production. Configurations, 2010, 18:363–382 © 2011 by The Johns Hopkins University Press and the Society for Literature and Science. -

The History of Cinema and America's Role in It: Review

Reason Papers Vol. 35, no. 1 The History of Cinema and America’s Role in It: Review Essay of Douglas Gomery and Clara Pafort- Overduin’s Movie History: A Survey Gary Jason California State University, Fullerton The book under review is an expanded and updated new edition of a book that was originally published a decade ago.1 The authors, Douglas Gomery and Carla Pafort-Overduin, have written a clear, comprehensive, and compelling history of cinema that is wonderfully useful as a reference text for philosophy and film courses, and as a main text for history of film courses. The book has some problems, however, which I will explore after I summarize its contents. The first section of the book (Chapters One through Five) discusses the silent era (1895-1925). The first chapter appropriately explores the earliest era of film, looking at the basic innovations. These innovations included magic lanterns (such as the 1861 patented kinematoscope), George Eastman’s celluloid-based film, the Lumiere brothers’ cameras and projectors, and Edison’s early crucial role in spreading the new technology. The authors also review the early era of film distribution and exhibition, through channels such as Vaudeville, fairs, and the nickelodeon. In Chapters Two and Three, Gomery and Pafort-Overduin discuss the early success of Hollywood, from the rise of the major studios and special venues (“picture palaces,” or large movie theaters) in 1917. They note a point to which I will return in due course, namely, that from roughly 1920 to 1950, the major Hollywood studios not only produced America’s films, but distributed and exhibited them (in their own movie theaters) as well.