European Emigration Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia

Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Assessorato allo Sviluppo Dipartimento Lavoro e Impresa Servizio Impresa e Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive BANDO RETI Legge 266/97 - Annualità 2011 Agevolazioni a favore delle piccole imprese e microimprese operanti nei quartieri: Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia, Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno, Ponticelli, Barra, San Giovanni a Teduccio, San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Stella, San Carlo Arena, Mercato, Pendino, Avvocata, Montecalvario, S.Giuseppe, Porto. Art. 14 della legge 7 agosto 1997, n. 266. Decreto del ministro delle attività produttive 14 settembre 2004, n. 267. Pagina 1 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 SOMMARIO ART. 1 – OBIETTIVI, AMBITO DI APPLICAZIONE E DOTAZIONE FINANZIARIA ART. 2 – REQUISITI DI ACCESSO. ART. 3 – INTERVENTI IMPRENDITORIALI AMMISSIBILI. ART. 4 – TIPOLOGIA E MISURA DEL FINANZIAMENTO ART. 5 – SPESE AMMISSIBILI ART. 6 – VARIAZIONI ALLE SPESE DI PROGETTO ART. 7 – PRESENTAZIONE DOMANDA DI AMMISSIONE ALLE AGEVOLAZIONI ART. 8 – PROCEDURE DI VALUTAZIONE E SELEZIONE ART. 9 – ATTO DI ADESIONE E OBBLIGO ART. 10 – REALIZZAZIONE DELL’INVESTIMENTO ART. 11 – EROGAZIONE DEL CONTRIBUTO ART. 12 –ISPEZIONI, CONTROLLI, ESCLUSIONIE REVOCHE DEI CONTRIBUTI ART. 13 – PROCEDIMENTO AMMINISTRATIVO ART. 14 – TUTELA DELLA PRIVACY ART. 15 – DISPOSIZIONI FINALI Pagina 2 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Art. 1 – Obiettivi, -

Past and Current Trends of Balkan Migrations

ESPACE, POPULATIONS, SOCIETES, 2004-3 pp. 519-531 Corrado BONIFAZI Istituto di Ricerche sulla Popolazione e le Politiche Marija MAMOLO Sociali IRPPS via Nizza, 128 Roma Italie [email protected] Past and Current Trends of Balkan Migrations INTRODUCTION There is hardly another region of the world aspects of the Balkans [Prévélakis, 1994], where the current situation of migrations is affecting their specific nature also with still considerably influenced by the past his- regard to migration. However, the migration tory as in the Balkans. Migrations have been outlook of the Balkans does not just involve a fundamental element in the history of the these flows, which in some respects tend to Balkans, accompanying its stormy events reflect the movements de l’histoire de [Her√ak and Mesi´c, 1990] and obviously longue durée, but it is rather much more continuing to do so, even at the start of the structured and complex. Focusing for the new millennium. For centuries, invasions, moment on the most recent period, together wars, military defeats and victories have with the forced migrations caused by the been a more or less direct cause of popula- ethnic conflicts in the former Yugoslavia tion movements, in a continuous and still and the ethnic migrations followed by the ongoing transformation of the distribution collapse of the regimes created by “real and the overlapping of religions, languages, socialism”, we find both forms of labour ethnic groups and cultures [Sardon, 2001]. migration and transit migration. Therefore, Since the arrival of the Slav populations in the Balkans are also characterised by many the 7th century, the Ottoman expansion, the of the typical elements of the current forms extension of the Hapsburg domain, the rise of mobility in Eastern and Central Europe and growth of national states, the two World [Okólski, 1998; Bonifazi, 2003]. -

Two Centuries of International Migration

IZA DP No. 7866 Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Timothy J. Hatton December 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Northwestern University Timothy J. Hatton University of Essex, Australian National University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 7866 December 2013 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

Global Migration and Regionalization, 1840-1940

UC Santa Cruz Mapping Global Inequalities Title Global Migration and Regionalization, 1840-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4t49t5zq Author McKeown, Adam Publication Date 2007-11-27 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California GLOBAL MIGRATION AND REGIONALIZATION, 1840-1940 Paper for conference on Mapping Global Inequalities Santa Cruz, California December 13-14, 2007 Adam McKeown Associate Professor of History Columbia University [email protected] The mass migrations of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a global phenomenon. From the North Atlantic to the South Pacific, hardly any corner of the earth was untouched by migration. These migrations similar in quantity and organization, and all linked through the processes of globalization: the peopling of frontiers, new transportation technologies, the production and processing of material for modern industry, the shipment and marketing of finished goods, and the production of food, shelter and clothing for people who worked in those industrial and distribution networks. It was a truly global process. Yet, the processes and cycles of migration grew increasingly integrated across the globe, the actual patterns and directions of migration grew more regionally segregated. These segregated regions experienced different patterns 2 of development and growth associated with migration. Moreover, this segregation helped to erase many of the non-Atlantic migrations from the historical memory, thus helping to obscure inequalities that were created as part of historical globalization by depicting certain parts of the world as having been outside of globalization. Most histories have recounted the age of mass migration as a transatlantic age. When migrations beyond the Atlantic are remembered at all, it is usually as a limited number of indentured laborers pressed into the service of Europeans. -

European and American Immigration Policies*

EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN IMMIGRATION POLICIES* PHILIP L. MARTINt AND MARION F. HOUSTOUN** I. INTRODUCTION Most of the world's 4,500,000,000 people never leave their country of birth. Those crossing national borders include five major groups: immigrants leaving one country to settle in another, refugees unwillingly fleeing their native land, workers temporarily living and working outside their country of citizenship, and temporary visitors--primarily students, business travelers, and tourists. In addi- tion to these legal migrants, people cross national borders illegally or enter a country legally (e.g., as a tourist) but later violate the terms of their legal admis- sion (usually by working). The magnitudes of these migrations are not known with certainty. Each year about 1,000,000 people leave one country to begin life as immigrants in another., The world's refugee population fluctuates, but has been in the 11,000,000 to 18,000,000 range during the 1970's.2 Another 20,000,000 to 30,000,000 persons live and work outside their country of citizenship, half as legal "guestworkers" and half as "illegal aliens."' 3 Since many countries do not record the entry and exit of temporary visitors from certain other countries, the number of tourists and other temporary visitors is not known, but probably exceeds several hundred million.4 Until the 19th century, "international migration" was of little concern because traditional migration, whether for economic betterment or to flee war or persecu- tion, did not involve the crossing of highly regulated national borders. Between 1840 and 1930, Europe, then the world's most densely populated region, sent more than 50,000,000 migrants to the Americas, South Africa, and Oceania.5 Within Copyright © 1983 by Law and Contemporary Problems * The ideas and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the institutions with which they are affiliated. -

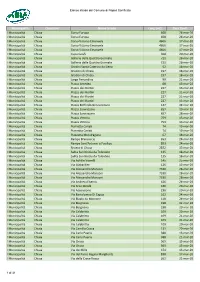

Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(Mt) Data Sanif

Elenco strade del Comune di Napoli Sanificate Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(mt) Data Sanif. I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24-mar-20 I Municipalità -

Del Comune Di Napoli

del comune di Napoli a cura del WWF Campania e della cooperativa La Locomotiva Centro di Documentazione CESPIA-CRIANZA Indagine sui servizi e la fruibilità dei Parchi e Giardini pubblici del comune di Napoli 3 Indice IL WWF A NAPOLI LA COOPERATIVA LA LOCOMOTIVA INTRODUZIONE E METODOLOGIA CARTA DEI PARCHI DEL COMUNE DI NAPOLI L’IMPORTANZA DELLE AREE VERDI E IL PROGRAMMA ECOREGIONALE DEL WWF DATI PRELIMINARI GLI INDICATORI UTILIZZATI CONCLUSIONI ALLEGATI: LE SCHEDE Municipalità no 1 Chiaia-S. Ferdiando-Posillipo Municipalità no 2 Avvocata-Mercato-Pendino-Porto-S. Giuseppe Municipalità no 3 Stella-S. Carlo all’Arena Municipalità no 4 S. Lorenzo-Vicaria-Poggioreale-Zona Industriale Municipalità no 5 Arenella-Vomero Municipalità no 6 Barra-S. Giovanni-Ponticelli Municipalità no 7 Miano-S. Pietro-Secondigliano Municipalità no 8 Chiaiano-Marianella-Piscinola-Scampia Municipalità no 9 Pianura-Soccavo Municipalità no 10 Bagnoli-Fuorigrotta ALLEGATI: APPROFONDIMENTI NATURALSITICI Bosco di Capodimonte Parco dei Camaldoli Parco del Poggio Parco Virgiliano Villa Comunale Villa Floridiana Parco Viviani RINGRAZIAMENTI E CREDITS Stesura e coordinamento gruppo di lavoro: Giovanni La Magna per il WWF, Anna Esposito per la cooperativa La Locomotiva. Hanno inoltre collaborato alla stesura del dossier: Giovanni La Magna, Ornella Capezzuto per il WWF, Anna Esposito, Marilina Cassetta per la cooperativa La Loco- motiva. Gli approfondimenti naturalistici sono stati curati da Anna Esposito e Giovanni La Magna, Nicola Bernardo, Giusy De Luca, Valerio Elefante, Martina Genovese, Natale Mirko, Antonio Pignalosa, Valerio Giovanni Russo, Andrea Sene- se, un gruppo di studenti di Scienze della Natura volontari del WWF. Gli approfondimenti del Real Parco di Capodi- monte, sono state fornite da Elio Esse. -

Rete Metropolitana Napoli 1.Pdf

aversa piedimonte matese benevento caserta caserta formia frattamaggiore casoria cancello afragola acerra casalnuovo di napoli botteghelle volla poggioreale centro direzionale underground and railways map madonnelle argine palasport salvator gianturco rosa villa gianturco visconti formia vesuvio barra de meis duomo san ponticelli giovanni porta nolana san s. maria giovanni del pozzo bartolo longo licola quarto quarto torregaveta centro san pietrarsa giorgio cavalli di bronzo bellavista portici ercolano pompei castellammare sorrento pompei salerno pozzuoli capolinea autobus edenlandia bus terminal kennedy linea 1 ANM linea 2 Trenitalia collegamento marittimo torregaveta agnano line 1 line 2 sea transfer pozzuoli gerolomini linea 6 ANM parcheggio metrocampania nordest EAV parking line 6 metrocampania nordest line bagnoli ospedale cappuccini dazio funicolari ANM hospital funicolars linea circumvesuviana EAV circumvesuviana railway museo stazione museum station linea circumflegrea EAV castello stazione dell’arte circumflegrea railway castle art station linea cumana EAV università stazione in costruzione cumana railway university station under construction stadio scale mobili rete ferroviaria Trenitalia stadium escalators regional and national railway network mostra d’oltremare nodi di interscambio collegamento aeroporto interchange station airport transfer ostello internazionale Porto - Stazione Centrale - Aeroporto hostelling international APERTURA CHIUSURA PUOI ACQUISTARE I BIGLIETTI PRESSO I open closed DISTRIBUTORI AUTOMATICI O NEI RIVENDITORI -

Elenco Beni Immobili

IMMOBILI POSSEDUTI DALL'AZIENDA - Anno 2017 PROV. Comune località / quartiere Indirizzo C.A.P. Denominazione sito DATI CASTALI NA NAPOLI Poggioreale v. cimitero israelita / via nuova Poggioreale 46 F 80143 COMPLESSO POGGIOREALE N.C.T. Foglio 82 particelle 365-366-367-368 NA NAPOLI Vomero calata S. Domenico n° 27 80127 SERBATOIO SANTO STEFANO N.C.T. Foglio 128 particella 431 NA CASORIA loc. Lufrano - Cittadella accesso da via Lufrano via Lufrano / via Nazionale delle Puglie accosto civ. 294 80026 COMPLESSO MAGAZZINI VOLLA N.C.E.U. Foglio 10 particella 127 sub 2 NA CASORIA loc. Lufrano - Cittadella Via Circumvallazione Esterna, 4 80026 COMPLESSO CENTRALI DI LUFRANO N.C.E.U. Foglio 13 particella 343 sub 1 NA NAPOLI Stella via Santa Maria la Catena loc. Fontanelle 80136 CENTRALE CATENA N.C.E.U. sez. AVV foglio 7 particella 364 sub 2 NA NAPOLI Stella salita di Capodimonte n° 80 80131 COMPLESSO SERBATOIO DI CAPODIMONTE N.C.T. Foglio 74 particelle 122-131-132 NA NAPOLI Stella v. Serbatoio Scudillo 10/11 Tangenziale 80131 COMPLESSO DELLO SCUDILLO N.C.E.U. sez. STE foglio 1 paricella 2019 sub 2 NA ACERRA Regi Lagni via Isonzo n° 47 81011 COMPLESSO REGI LAGNI N.C.T. foglio 21 particella 21 sub 2 NA ACERRA Gaudello via provinciale Gaudello n° 3 81011 COMPLESSO MOFITO N.C.E.U. foglio 21 particella 21 sub 1 NA NAPOLI Avvocata via Ventaglieri n° 85 80135 COMPLESSO AGENZIA VENTAGLIERI N.C.E.U. sez. AVV foglio 11 particella 512 sub 7e 107 e particella 542 sub 1 NA NAPOLI Chiaia v. -

Municipalità 1 - Chiaia, Posillipo, S

Indirizzi e contatti delle Municipalità cittadine Municipalità 1 - Chiaia, Posillipo, S. Ferdinando Sede Telefoni e fax Email Servizi Demografici Tel. 0817950512 [email protected] Chiaia - S.Ferdinando - Posillipo Fax 0817950502 [email protected] via S.Caterina a Chiaia, 76 [email protected] [email protected] Municipalità 2 - Avvocata, Montecalvario, Mercato, Pendino, Porto, S. Giuseppe Sede Telefoni e fax Email Ufficio anagrafe - Piazza Dante n. Fax 081 7950286 [email protected] 93 - 80135 Napoli (per i quartieri - 081 7950209 [email protected] Avvocata - Montecalvario - San Giuseppe - Porto) Municipalità 3 - Stella, S. Carlo all'Arena Sede Telefoni e fax Email Sezione San Carlo - Via Lieti, 97 Tel. 081 7952419 [email protected] 80131 Napoli Fax 081 7952451 municipalità[email protected] Sezione San Carlo - Via SS. Tel. 081 7952512 [email protected] Giovanni e Paolo, 125 Fax 081 7952501 municipalità[email protected] 80137 Napoli Sezione Stella - Via Sant'Agostino Tel. 081 7952632 [email protected] degli Scalzi, 61 80136 Napoli Fax 081 7952609 municipalità[email protected] Municipalità 4 - S. Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Zona Industriale Sede Telefoni e fax Email Ufficio Anagrafe di Poggioreale Tel. 081 7951317 [email protected] via E. Gianturco 99 - 80142 - Fax 081 7951378 [email protected] Napoli Ufficio Anagrafe di San Lorenzo Tel.081 7951918 [email protected] via Tribunali 227 - 80138 - Napoli Fax 081 7951934 [email protected] Municipalità 5 - Arenella, Vomero Sede Telefoni e fax Email Vomero Via Raffaele Morghen n. -

4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 10 7 7 5 6 4 8 10 6 6 6 6 8 7

TIPOLOGIA INTER TOPONIMO QUARTIERE MUN SOTTOPASSO (CDN) A/B Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) B5/B6 Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) C1/C9 Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO DELLA (CDN) COSTITUZIONE Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) E/F Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) F/G Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) LAURIA Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) MALTA Poggioreale 4 PARCHEGGIO (CDN) P9 Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) PORZIO Poggioreale 4 PARCHEGGIO (CDN) T2 Poggioreale 4 SOTTOPASSO (CDN) TADDEO DA SESSA Poggioreale 4 STRADA DETTA A MURO SCOPERTO Bagnoli 10 VIA ABATE GIOACCHINO Miano 7 VIA ABATE GIOACCHINO Secondigliano 7 VIA ABATE SERGIO Arenella 5 VIA ABATI ALESSANDRO Ponticelli 6 VIA ABBA GIUSEPPE CESARE S.Lorenzo 4 LARGO ABBAGNANO NICOLA Scampia 8 VIA VICINALE ABBANDONATA DEGLI ASTRONI Bagnoli 10 CONTRADA DETTA ABBASSO MARANDA Ponticelli 6 PIAZZA ABBEVERATOIO Barra 6 TRAVERSA ABBEVERATOIO Barra 6 VIA ABBEVERATOIO Barra 6 VIA DELL' ABBONDANZA Piscinola 8 VIA ABRUZZI Miano 7 VIA ACATE Bagnoli 10 VICO ACITILLO Vomero 5 VIA DEGLI ACQUARI Porto 2 VIALE DELL' ACQUARIO Secondigliano 7 VIA COMUNALE ACQUAROLA Miano 7 VIA COMUNALE ACQUAROLA Secondigliano 7 CUPA ACQUAROLA DI PISCINOLA Piscinola 8 VIA ACQUAVIVA MATTEO ANDREA Vicaria 4 VIA ACTON AMMIRAGLIO FERDINANDO S.Ferdinando 1 VIA ADIGE Fuorigrotta 10 VIA ADIGE Soccavo 9 VIA ADRIANO Soccavo 9 VIA AGANOOR VITTORIA Piscinola 8 VIA AGELLO FRANCESCO S.Pietro a Pat. 7 1 di 97 TIPOLOGIA INTER TOPONIMO QUARTIERE MUN VIA AGEROLA S.Giov.a Ted 6 VIA NUOVA DI AGNANO Bagnoli 10 VIA NUOVA DI AGNANO Fuorigrotta 10 VIA VECCHIA DI -

The Sinews of Spain's American Empire: Forced Labor in Cuba from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries1

chapter 1 The Sinews of Spain’s American Empire: Forced Labor in Cuba from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries1 Evelyn P. Jennings The importance of forced labor as a key component of empire building in the early modern Atlantic world is well known and there is a rich scholarly bibliog- raphy on the main forms of labor coercion that European colonizers employed in the Americas—labor tribute, indenture, penal servitude, and slavery. Much of this scholarship on forced labor has focused on what might be called “pro- ductive” labor, usually in the private sector, and its connections to the growth of capitalism: work to extract resources for sustenance, tribute, or export. This focus on productive labor and private entrepreneurship is particularly strong in the scholarship on the Anglo-Atlantic world, especially the shifting patterns of indenture and slavery in plantation agriculture, and their links to English industrial capitalism.2 The historical development of labor regimes in the Spanish empire, on the other hand, grew from different roots and traversed a different path. Scholars have recognized the importance of government regulations (or lack thereof) as a factor in the political economy of imperial labor regimes, but rarely are 1 The author wishes to thank the anonymous readers and the editors at Brill and Stanley L. Engerman for helpful comments. She also thanks all the participants at the Loyola University conference in 2010 that debated the merits of the first draft of this essay, as well as Marcy Norton, J.H. Elliott, Molly Warsh and other participants for their comments on a later draft presented at the “‘Political Arithmetic’ of Empires in the Early Modern Atlantic World, 1500–1807” conference sponsored by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of Maryland in March 2012.