Lessons Learned from the French Meadows Project Citation: Edelson, David and Hertslet, Angel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Preparedness and Evacuation Plan

Squaw Valley Real Estate, LLC Emergency Preparedness and Evacuation Plan THE VILLAGE AT SQUAW VALLEY 6/28/2016 This Emergency Preparedness and Evacuation Plan (EPEP) has been prepared for The Village at Squaw Valley Specific Plan (VSVSP) project under the supervision of Placer County and in coordination with Pete Hnat, Chief Executive Officer, Emergency Management Consultants. The focus of the EPEP is primarily on emergency preparedness and evacuation protocols as related to emergency events, such as fire. However, other hazards are addressed as well, including avalanche, seismic and flood protection measures. Emergency Preparedness and Evacuation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 4 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Project Summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.3.1 Location .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3.2 Project Description ................................................................................................................ 6 2.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS .................................................................... -

Squaw Valley |Alpine Meadows Base-To-Base Gondola Project Draft EIS/EIR 4.3-1 Wilderness SE Group & Ascent Environmental

SE Group & Ascent Environmental Wilderness 4.3 WILDERNESS This section includes discussion of potential impacts of the proposed Base-to-Base Gondola project on the National Forest System-Granite Chief Wilderness (GCW), which is adjacent to the project area (i.e., the area generally encompassed by all three action alternatives). No construction, and therefore no direct effects, would occur on National Forest System (NFS) lands within the GCW. However, indirect impacts on its wilderness character and wilderness users could occur, as described below. This section additionally assesses impacts associated with a portion of privately owned land that was included within the area mapped by Congress as part of the GCW within the 1984 California Wilderness Act. For clarity, this section references the NFS lands within the GCW as “National Forest System-GCW” and refers to the privately owned land included within the congressionally mapped wilderness boundary as “private lands within the congressionally mapped GCW.” In accordance with the Wilderness Act of 1964, federally-managed Wilderness areas, like the National Forest System-GCW, are defined as follows: (c) A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this Act an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without -

Bear Creek Watershed Assessment Report

BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT PLACER COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Prepared by: PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96162 February 16, 2018 And Dr. Susan Lindstrom, PhD BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA February 16, 2018 A REPORT PREPARED FOR: Truckee River Watershed Council PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96161 (530) 550-8760 www.truckeeriverwc.org by Brian Hastings Balance Hydrologics Geomorphologist Matt Wacker HT Harvey and Associates Restoration Ecologist Reviewed by: David Shaw Balance Hydrologics Principal Hydrologist © 2018 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. Project Assignment: 217121 800 Bancroft Way, Suite 101 ~ Berkeley, California 94710-2251 ~ (510) 704-1000 ~ [email protected] Balance Hydrologics, Inc. i BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA < This page intentionally left blank > ii Balance Hydrologics, Inc. BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Project Goals and Objectives 1 1.2 Structure of This Report 4 1.3 Acknowledgments 4 1.4 Work Conducted 5 2 BACKGROUND 6 2.1 Truckee River Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) 6 2.2 Water Resource Regulations Specific to Bear Creek 7 3 WATERSHED SETTING 9 3.1 Watershed Geology 13 3.1.1 Bedrock Geology and Structure 17 3.1.2 Glaciation 18 3.2 Hydrologic Soil Groups 19 3.3 Hydrology and Climate 24 3.3.1 Hydrology 24 3.3.2 Climate 24 3.3.3 Climate Variability: Wet and Dry Periods 24 3.3.4 Climate Change 33 3.4 Bear Creek Water Quality 33 3.4.1 Review of Available Water Quality Data 33 3.5 Sediment Transport 39 3.6 Biological Resources 40 3.6.1 Land Cover and Vegetation Communities 40 3.6.2 Invasive Species 53 3.6.3 Wildfire 53 3.6.4 General Wildlife 57 3.6.5 Special-Status Species 59 3.7 Disturbance History 74 3.7.1 Livestock Grazing 74 3.7.2 Logging 74 3.7.3 Roads and Ski Area Development 76 4 WATERSHED CONDITION 81 4.1 Stream, Riparian, and Meadow Corridor Assessment 81 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. -

French Meadows Forest Restoration Project February 2019

French Meadows Forest Restoration Project February 2019 The 28,000-acre French Meadows Forest Restoration Project is using a collaborative, all-lands approach to restore forest health and resilience and reduce the risk of high-severity wildfire in the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the American River, a critical municipal watershed located on the Tahoe National Forest in California’s Sierra Nevada. The Project was developed by a diverse partnership, including the U.S. Forest Service, which manages most of the land within the project area; Placer County Water Agency, which manages two reservoirs downstream of the project for municipal water and hydropower; The Nature Conservancy, one of the world’s largest conservation organizations; the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state agency and funder; Placer County, a business partner in the hydropower project; the American River Conservancy, an adjacent private landowner; and the Sierra Nevada Research Institute at UC Merced. The French Meadows Project aims to accelerate ecologically-based forest and watershed restoration on the Tahoe National Forest through a shared stewardship approach involving: • Collaborative Management. The partners co-led development of the project and hired consultants to undertake planning and environmental analysis, substantially reducing the planning time for similar Forest Service projects. • Diverse Fundraising. The partners raised funds from a wide variety of federal, state, local, and private sources, including significant investment from downstream water beneficiaries like the water utility and private beverage companies. • Innovative Project Implementation. Placer County will hire contractors to implement thinning and other mechanical treatments, under a Master Stewardship Agreement with the Forest Service. The Nature Conservancy and the Forest Service will work together to develop and implement a prescribed burn plan. -

UPDATE VOL 23 NO 4 AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2009 PLACER COUNTY WATER AGENCY Water • Energy • Stewardship

UPDATE VOL 23 NO 4 AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2009 PLACER COUNTY WATER AGENCY water • energy • stewardship IN THIS ISSUE: Helping to Plan Tahoe Water Supplies... Page 2 Placer Students Are Water Aware... Page 3 Update for an Old Dam Two-Year Project to Improve Spillway at French Meadows ollowing eight years of studies, planning and design, PCWA is preparing to rebuild key sec- tions of the almost 50-year-old dam that holds back water at French FMeadowsF Reservoir. L.L. Anderson Dam, named for the late Foresthill Divide community leader, and District 5 county supervisor and PCWA director, was built in 1963-66 as a key feature of PCWA’s Middle Fork Regulatory Commission confirmed the Mountain Waterworks American River Project. Corps’ conclusion. The spillway at French Meadows, above, French Meadows Reservoir holds Probable Maximum Flood at left, will be upgraded after studies 136,400 acre-feet of water and is situated Using modern hydrometerological showed that it is too small to handle a at 5200 feet on the western slope of the data, the Corps developed a 72-hour maximum probable flooding event. Sierra Nevada. Lake Tahoe lies about 18 Probable Maximum Precipitation (PMP) miles to the east. Donner Summit is depth of 46 inches for the French about 15 miles north. Meadows watershed. This computed to a be overtopped,” said PCWA Hydroelectric In 2001, the U.S. Army Corps of French Meadows inflow of 66,700 cubic Engineer Jon Mattson. “This could cause Engineers first released hydrologic studies feet per second, which could overtop the failure of the dam and significant down- showing that the existing L.L. -

The Genesis of the Placer County Water Agency

a Heritage of Water: The Golden Anniversary of the Placer County Water Agency 1957-2007 Prepared by the Water Education Foundation Placer County History Book WEB1 9/10/2007, 3:08 PM Credits This book was prepared and published by the Water Education Foundation in conjunction with the Placer County Water Agency. The book tells the story of Placer County water from its role in the Gold Rush to the formation of the Placer County Water Agency, which has managed the county’s water resources for 50 years. Editor: Sue McClurg Authors: Ryan McCarthy, Janet Dunbar Fonseca, Ed Tiedemann, Ed Horton, Cheri Sprunck, Dave Breninger and Einar L. Maisch Design and Layout: Graphic Communications Printing: Paul Baker Printing Photos: Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley • William Briner • California State Archives (F3757:3) • California State Library • California State Parks – Auburn State Recreation Area Collection • Dave Carter • City of Rocklin • Placer County Water Agency • Ryan Salm/Sierra Sun • Special Collections, University of California, Davis • U.S. Bureau of Reclamation • USDA NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) • U.S. National Forest Campground Guide • Karina Williams/Lincoln News Messenger • Bill Wilson On the cover: Hell Hole Reservoir (top) and building the Middle Fork Project PLACER COUNTY WATER AGENCY P.O. Box 6570 717 K Street, Suite 317 144 Ferguson Road Sacramento, CA 95814 Auburn, CA 95604 (916) 444-6240 (530) 823-4850 www.watereducation.org www.pcwa.net Copyright 2007 by Water Education Foundation • All rights reserved ISBN 1-893246-97-3 2 Placer County History Book WEB2 9/10/2007, 3:09 PM Foreword by David A. -

Upper American River Hydroelectric Project (P-2101)

Hydropower Project Summary UPPER AMERICAN RIVER, CALIFORNIA UPPER AMERICAN RIVER HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2101) South Fork of the American River Slab Creek Dam Canyon Photo Credit: Sacramento Municipal Utility District This summary was produced by the Hydropower Reform Coalition and River Management Society Upper American, CA UPPER AMERICAN RIVER, CA UPPER AMERICAN RIVER HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2101) DESCRIPTION: The Upper American River Project consists of seven developments located on the Rubicon River, Silver Creek, and South Fork American River in El Dorado and Sacramento Counties in central California. These seven developments occupy 6,190 acres of federal land within the Eldorado National Forest and 54 acres of federal land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The proposed The Iowa Hill Development will be located in El Dorado County and will occupy 185 acres of federal land within the Eldorado National Forest. Due to the proximity of the Chili Bar Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 2155) under licensee Pacific Gas & Electric Company(PG&E) located immediately downstream of the Upper American Project on the South Fork American River (and also under-going re-licensing), both projects were the subject of a collaborative proceeding and settlement negotiations. The current seven developments include Loon Lake, Robbs Peak, Jones Fork, Union Valley, Jaybird, Camino, and Slab Creek/White Rock. White Rock Powerhouse discharges into the South Fork American River just upstream of Chili Bar Reservoir. In addition to generation-related facilities, the project also includes 47 recreation areas that include campgrounds, day use facilities, boat launches, trails, and a scenic overlook. The 19 signatories to the Settlement are: American Whitewater, American River Recreation Association, BLM, California Parks and Recreation, California Fish and Wildlife, California Outdoors, California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, Camp Lotus, Foothill Conservancy, Forest Service, Friends of the River, FWS, Interior, U.S. -

Appendix C: Evaluation of Areas for Potential Wilderness

Appendices for the FEIS Appendix C: Evaluation of Areas for Potential Wilderness Introduction This document describes the process used to evaluate the wilderness potential of areas on the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit (LTBMU). The March 2009 inventory conducted according to Forest Service Handbook 1909.12, Chapter 70, 2007 is the basis for this evaluation. The LTBMU was evaluated to determine landscape areas that exhibited inherent basic wilderness qualities such the degree of naturalness and undeveloped character. In addition to the wilderness qualities an area might possess, the area must also provide opportunities and experiences that are dependent on and enhanced by a wilderness environment and area boundaries that could be managed as wilderness. It was determined that areas adjacent to existing wilderness and existing Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs) were areas were most likely to have the characteristics described above. Other areas around the basin exhibited some of the required characteristics but not enough to be qualified for a congressional wilderness designation. Six areas were identified and evaluated. The analysis is based on GIS mapping of existing wilderness and inventoried roadless area polygon data, adjusted based on local knowledge. Three tests were used—capability, availability, and need—to determine suitability as described in Forest Service Handbook 1909.12, Chapter 70, 2007. In addition to the inherent wilderness qualities an area might possess, the area must provide opportunities and experiences that are dependent on and enhanced by a wilderness environment. The area and boundaries must allow the area to be managed as wilderness. Capability is defined as the degree to which the area contains the basic characteristics that make it suitable for wilderness designation without regard to its availability for or need as wilderness. -

Overview of Existing Resources

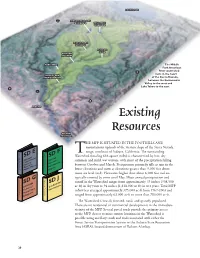

M I dd L E F O R K 80 A M E R I C A N FRENCH MEADOWS RESER VOIR HELL HOLE R LAKE RESER IVERTAHOE PROJECT VOIR MIDDLE FORK INTERBAY RALSTON AFTERBAY FORESTHILL RUBICON 49 MIDDLE FORK RIVER AMERICAN RIVER 80 AUBURN 50 The Middle Fork 49 River watershed rests in the heartAmerican of the Sierra Nevada, between the Sacramento V Lake alley to the west and Tahoe to the east. S FOLSOM u p p RESER o r t VOIR i n g D SD E o Existing c u Relevant S m u p e p n Comprehensive o t r E Plans & t i n g Resource D SD F o Resources Mgmt. Plans HE MFP IS SITUATED IN THE FOOTHILLS AND c u Existing m e n Resource mountainous uplands of the western slope of the Sierra Nevada t S F u p Information p WatershedT (totaling 616 square miles) is characterized by hot, dry range, northeast of Auburn, California. The surrounding o r Report t i n g summers and mild, wet winters, with most of the precipitation falling D SD G o c S u 00/00 between October and March. Precipitation primarily falls as rain in the u m p p e n Technical o t r lower elevations and snow at elevations greater than 5,000 feet above t G i Study Plans n g D SD J mean sea level (msl). Elevations higher than about 6,000 feet msl are & Reports o c u Confi dential m e typically covered by snow until May. -

2040 Placer County Regional Transportation Plan

INITIAL STUDY AND NOTICE OF PREPARATION FOR THE 2040 PLACER COUNTY REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN JUNE 6, 2019 Prepared for: Placer County Transportation Planning Agency 299 Nevada St. Auburn, CA 95603 (530) 823-4032 Prepared by: De Novo Planning Group 1020 Suncast Lane, Suite 106 El Dorado Hills CA 95762 (916) 580-9818 De Novo Planning Group A Land Use Planning, Design, and Environmental Firm INITIAL STUDY AND NOTICE OF PREPARATION FOR THE 2040 PLACER COUNTY REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN JUNE 6, 2019 Prepared for: Placer County Transportation Planning Agency 299 Nevada St. Auburn, CA 95603 (530) 823-4030 Prepared by: De Novo Planning Group 1020 Suncast Lane, Suite 106 El Dorado Hills CA 95762 (916) 580-9818 2040 PLACER COUNTY RTP NOP NOTICE OF PREPARATION TO: FROM: EIR Consultant: State Clearinghouse Placer County Transportation Planning Steve McMurtry, Principal Planner State Responsible Agencies Agency De Novo Planning Group State Trustee Agencies Aaron Hoyt, Associate Planner 1020 Suncast Lane, Suite 106 Other Public Agencies 299 Nevada St. El Dorado Hills, Ca 95762 Interested Organizations Auburn, CA 95603 (530) 823-4032 SUBJECT: Notice of Preparation – 2040 Placer County Regional Transportation Plan Placer County Transportation Planning Agency (PCTPA) is in the process of updating the Placer County Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) and has determined that the update is subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). CEQA requires the preparation of an environmental impact report (EIR) prior to approving any project that may have a significant impact on the environment. The CEQA Guidelines identify several types of EIRs, each applicable to different project circumstances. The PCTPA intends to prepare a Program EIR pursuant to CEQA Guidelines Section 15168. -

Motorized Travel Management Draft Environmental Impact Statement – September 2008 Chapter 3: Affected Environment & Environmental Consequences – 3.08

Motorized Travel Management Draft Environmental Impact Statement – September 2008 Chapter 3: Affected Environment & Environmental Consequences – 3.08. Transportation 3.08. Transportation _____________________________________ Affected Environment Introduction This section of the environmental analysis examines the extent to which alternatives respond to transportation facilities direction established in the Tahoe National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan. The Forest Plan transportation facilities direction was established under the implementing regulations of the National Forest Management Act (NFMA) and the National Forest Roads and Trails Act (FRTA). The National Forest Transportation System (NFTS) consists of roads, trails, airfields, and areas. The NFTS provides for protection, development, management, and utilization of resources on the National Forests. There are other roads and trails existing on the Forest that are not currently part of the NFTS. Transportation facilities considered in this analysis include roads and trails that are suitable for motor vehicle use. This analysis considers changes needed to the NFTS to meet the purpose and need of this analysis. Decisions regarding changes to the transportation facilities must consider: 1) providing for adequate public safety, and 2) providing adequate maintenance of the roads and trails that will be designated for public use. The analysis in this section primarily focuses on these two aspects of the NFTS. Background A majority of national forest visitors travel on national forest system roads. Roads have opened the Tahoe National Forest to millions of national and international visitors. Forest roads are also an integral part of the transportation system for rural counties. They provide access for research, fish and wildlife habitat management, grazing, timber harvesting, fire protection, mining, insect and disease control, and private land use. -

Nevada County Recreation and Parks Services Municipal Services Review

NEVADA COUNTY RECREATION AND PARKS SERVICES MUNICIPAL SERVICES REVIEW Prepared for: NEVADA COUNTY LOCAL AGENCY FORMATION COMMISSION 950 Maidu Avenue Nevada City, CA 95959 Prepared by: PACIFIC MUNICIPAL CONSULTANTS 10461 Old Placerville Road, Suite 110 Sacramento, CA 95827 Phone: 916.361.8384 Fax: 916.361.1574 April 2006 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS LAFCo Resolution 06-04 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ ES-1 Regional Determinations ................................................................................................................. ES-1 Selected Agency Determinations................................................................................................... ES-4 I. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1-1 A) Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ I-1 B) Local Agency Formation Commission Responsibilities............................................................. I-1 C) Nevada County LAFCo Policies and Procedures for Spheres of Influence.......................... I-2 D) Municipal Service Review Guidelines ......................................................................................... I-2 E) Methodology .................................................................................................................................