Australia and the Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Round 8 2020 Volume 1 · Issue 6

The FRONT ROW ROUND 8 2020 VOLUME 1 · ISSUE 6 The long roadFrom Temora to Belmore,back how Joe Stimson plans to bark back INSIDE: RUGBY LEAGUE 'SCORIGAMI' · CROSSWORD & WORD JUMBLES · RESULTS REPORTS · LADDER · STATS LEADERS · NEWS · R8 TEAMLISTSLEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM & PREVIEWS | THE FRONT ·ROW 2020 | ROUND DRAW 8, 2020 | 1 THE FRONT ROW FORUMS AUSTRALIA’S BIGGEST RUGBY LEAGUE DISCUSSION FORUMS forums.leagueunlimited.com THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | ROUND 8, 2020 From the editor What’s inside Tim Costello THE FRONT ROW - ISSUE 6 The 'new normal' is definitely here - while most teams and From the editor 3 grounds will be welcoming back fans in greater numbers this THE WRAP · Round 7 weekend, there's trepidation about what the Victorian outbreak in COVID-19 means for the immediate future of professional Match reports 4-7 sport. The scoresheet 8 For what it's worth, the Storm have made a noble, Warriors- LU Player of the Year standings 9 esque sacrifice and will base themselves in Queensland for the NRL Match Review & Judiciary 9 interim, using Sunshine Coast - already a feeder club - as their training base while playing matches at Brisbane's Suncorp Premiership Ladder, Stats Leaders 10 Stadium. From the NRL, Player Birthdays 11 Meanwhile on the field - the pressure is really being turned Feature: Joe Stimson 12-13 up on Brisbane's Anthony Seibold and Canterbury's Dean Pay RLP's rugby league 'Scorigami' 14-15 as the two proud clubs prop up the NRL ladder this week. The Broncos haven't won a match since the premiership restarted Fun & Games: Crossword & Jumbles 16 in May and Canterbury have fared little better, picking up GAME DAY · Round 8 17 just the one victory across those five weeks. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 21st September 2016 Newsletter #140 By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan RIKEY DID the Vodafone Warriors get hammered at the weekend. The constant theme was that we Cneed a player clearout. That is hardly groundbreaking stuff, but what was, was that players were named. Hugh McGahan singled out Manu Vatuvei and Ben Matulino, arguing both had failed to live up their status as two of our highest paid players. The former Kiwi captain said Warriors coach Stephen Kearney could make a mark by showing the pair the door, and proving to the others that poor performances won't be tolerated. “Irrespective of his standing, Manu Vatuvei has got to go,” McGahan told Tony Veitch. “And again, irre- spective of his standing, Ben Matulino has got to go. They have underperformed. If you're going to make an impact I'd say that's probably the two players that you would look at.” Bold stuff, and fair play to the man, he told it like he saw it. Kearney, on the other hand, clearly doesn’t see it the same way, since he named both in the Kiwis train-on squad, and while he acknowledged they had struggled this year, he backed himself to get the best out of them. In fact he went further, he said it was his job. “That's my responsibility as the coach, to get the individuals in a position so they can go out and play their best. -

Mad Butcher Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch’s Mad Butcher Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 2015 Dick Smith NRL Auckland Nines Special Edition Newsletter Dick Smith NRL Auckland Nines Details Date: This Saturday 31st January and Sunday 1st February, 2015 Time: Saturday - Gates open: 11:30am - Event commences: 12:00pm - Gates close: 8:30pm Sunday - Gates open 10:00am - Event commences: 11:10am - Event ends: 8:30pm Venue: Eden Park, Mt Eden, Auckland Parking/Transport: There is no parking on-site. However complimentary public transport to and from Eden Park on special services is included with your ticket; just present your ticket upon boarding. For more info visit: www.AT.co.nz/info/events.aspx Please note there is only ONE ticket for BOTH days so please keep your ticket safe. Ensure everyone brings their ticket each day as it will be required for entry. Please also read the condi- tions of entry to Eden Park at www.edenpark.co.nz and rules of play that are in the newsletter. Buy tickets at www.ticketek.co.nz/nrlakl9s To ensure everyone has a great can be consumed on transport at No commercially bought food (e.g weekend, the organisers have any time. McDonalds, KFC, Burger King some rules of play that must be etc) may be brought into the ven- adhered to: If you have purchased tickets to ue, but you are welcome to bring the family zone, note that this is small amounts of non-commer- A liquor ban will be enforced in an alcohol free zone and no al- cially produced food for personal the neighbourhood surrounding cohol may be purchased or con- consumption. -

Two Kiwis on Their Way out of NRL: Kiwis Coach Stephen Kearney Is Philosophical About Two Kiwis Leaving the NRL to Pick up More Money in England

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 18 May 2009 RE: Media Summary Tuesday 12 April to Monday 18 May 2009 They are happy helping others: One helps out people from the other side of the world, one mentors the troubled kids at her league club, and another just looks after his mum. What the five winners of this year's Young Community Leaders Awards have in common, though, is a dedication to social work, rather than their social lives. Emma Daken, Teresa Edge, Henare Mihaere, Fofo Molia and Libby Tuite were chosen from nearly 60 nominees to receive the awards, which recognised Wellingtonians under the age of 25 working in the not-for- profit sector, either as a volunteer or in a paid position. Anzac test to stay - and it'll be in Brisbane: Despite the Kiwis' dire results in mid-year tests across the Tasman, the Anzac league test is likely to survive and remain in Brisbane because the New Zealand Rugby League cannot afford to host the game. NZRL chairman Ray Haffenden admits there are conflicting views about the test's value after New Zealand's run of eight successive defeats but has given it his backing and said the league cannot afford to scrap the game, nor host it. No sign of league World Cup cash: Six months since the World Cup final, the much-trumpeted tournament profit apparently still sits in a Rugby League International Federation bank account. New Zealand has not been told what the final profit is, or how it will be distributed and RLIF boss Colin Love couldn't be reached last night. -

Tackling Violence Evaluation

TACKLING VIOLENCE EVALUATION WOMEN NSW FINAL REPORT 21 OCTOBER 2019 Final report Tackling Violence evaluation Acknowledgments This work was completed with the assistance of staff from Women NSW of the Department of Communities and Justice and the NSW Education Centre Against Violence. We would also like to thank the many players and club leaders from the six participating rugby league clubs we visited, as well as other key community, service provider and program- level stakeholders. We thank them for their time and insights and trust that their views are adequately represented in this report. ARTD consultancy team Fiona Christian, Sue Leahy, Ruby Leahy Gatfield, Samantha Joseph, Jack Cassidy, Holly Kovac, Kieran Sobels and Pravin Siriwardena ARTD Pty Ltd Level 4, 352 Kent St Sydney ABN 75 003 701 764 PO Box 1167 Tel 02 9373 9900 Queen Victoria Building Fax 02 9373 9998 NSW 1230 Australia Final report Tackling Violence evaluation Contents Executive summary................................................................................................................. vi 1. The program ................................................................................................................. 14 1.1 The policy context.......................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 The program .................................................................................................................................... 14 2. The evaluation ............................................................................................................. -

THE 300 CLUB (39 Players)

THE 300 CLUB (39 players) App Player Club/s Years 423 Cameron Smith Melbourne 2002-2020 372 Cooper Cronk Melbourne, Sydney Roosters 2004-2019 355 Darren Lockyer Brisbane 1995-2011 350 Terry Lamb Western Suburbs, Canterbury 1980-1996 349 Steve Menzies Manly, Northern Eagles 1993-2008 348 Paul Gallen Cronulla 2001-2019 347 Corey Parker Brisbane 2001-2016 338 Chris Heighington Wests Tigers, Cronulla, Newcastle 2003-2018 336 Brad Fittler Penrith, Sydney Roosters 1989-2004 336 John Sutton South Sydney 2004-2019 332 Cliff Lyons North Sydney, Manly 1985-1999 330 Nathan Hindmarsh Parramatta 1998-2012 329 Darius Boyd Brisbane, St George Illawarra, Newcastle 2006-2020 328 Andrew Ettingshausen Cronulla 1983-2000 326 Ryan Hoffman Melbourne, Warriors 2003-2018 325 Geoff Gerard Parramatta, Manly, Penrith 1974-1989 324 Luke Lewis Penrith, Cronulla 2001-2018 323 Johnathan Thurston Bulldogs, North Queensland 2002-2018 323 Adam Blair Melbourne, Wests Tigers, Brisbane, Warriors 2006-2020 319 Billy Slater Melbourne 2003-2018 319 Gavin Cooper North Queensland, Gold Coast, Penrith 2006-2020 318 Jason Croker Canberra 1991-2006 317 Hazem El Masri Bulldogs 1996-2009 316 Benji Marshall Wests Tigers, St George Illawarra, Brisbane 2003-2020 315 Paul Langmack Canterbury, Western Suburbs, Eastern Suburbs 1983-1999 315 Luke Priddis Canberra, Brisbane, Penrith, St George Illawarra 1997-2010 313 Steve Price Bulldogs, Warriors 1994-2009 313 Brent Kite St George Illawarra, Manly, Penrith 2002-2015 311 Ruben Wiki Canberra, Warriors 1993-2008 309 Petero Civoniceva Brisbane, -

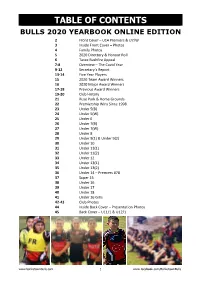

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS BULLS 2020 YEARBOOK ONLINE EDITION 2 Front Cover – U14 Premiers & U7/W 3 Inside Front Cover – Photos 4 Family Photos 5 2020 Directory & Honour Roll 6 Taree Bushfire Appeal 7-8 Overview – The Covid Year 9-12 Secretary’s Report 13-14 Five Year Players 15 2020 Team Award Winners 16 2020 Major Award Winners 17-18 Previous Award Winners 19-20 Club History 21 Ruse Park & Home Grounds 22 Premiership Wins Since 1998 23 Under 5(B) 24 Under 5(W) 25 Under 6 26 Under 7(B) 27 Under 7(W) 28 Under 8 29 Under 9(1) & Under 9(2) 30 Under 10 31 Under 11(1) 32 Under 11(2) 33 Under 12 34 Under 13(1) 35 Under 13(2) 36 Under 14 – Premiers #78 37 Super 15 38 Under 16 39 Under 17 40 Under 18 41 Under 16 Girls 42-43 Club Photos 44 Inside Back Cover – Presentation Photos 45 Back Cover – U11/1 & U12/1 www.bankstownbulls.com 1 www.facebook.com/BankstownBulls 2020 YEARBOOK FAMILY PHOTOS www.bankstownbulls.com 4 www.facebook.com/BankstownBulls 2020 DIRECTORY & HONOUR ROLL 2020 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE CBDJRL CLUB’S CLUB OF THE YEAR President: Ali Mehanna 2019 Bankstown Bulls (inaugural winner) Secretary: Matthew O’Neill MAJOR SPONSOR Treasurer: Rabab Raad Bankstown RSL Club Senior Vice President: Stan Hetaraka Assistant Secretary: Anthony Samuel SCOREBOARD SPONSOR First Option Bank 2020 GENERAL COMMITTEE Junior Vice President: David Tarabay JERSEY SPONSORS Canteen: Sandra Chahine Bankstown RSL Club / Star Buffet Bankstown Legal & Covid Officer: Hussein Dia Mortimer Apparel Cedar Beverages DELEGATES TO CBDJRL & BULLDOGS Ground King Civil Matthew O'Neill; -

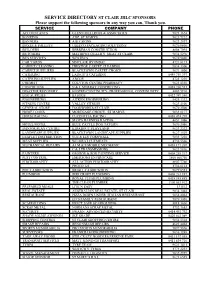

SERVICE DIRECTORY ST CLAIR JRLC SPONSORS Please Support the Following Sponsors in Any Way You Can, Thank You

SERVICE DIRECTORY ST CLAIR JRLC SPONSORS Please support the following sponsors in any way you can, Thank you. SERVICE COMPANY PHONE ACCOUNTANTS GLENN MELLROSS & ASSOCIATES 9623 1624 BANKING ANZ, ST MARYS 9623 7222 BANNERS A B F SIGNS 9623 2937 BOXES & PALLETS UBEECO PACKAGING SOLUTIONS 9670 9800 BUILDERS BERRIMAN CONSTRUCTION 8808 7095 BUTCHERS MATHEWS QUALITY MEAT ST CLAIR 9834 5296 BUS SERVICES WESTBUS 9670 9800 CAR YARDS SINCLAIR HYUNDAI 4721 8171 CARPET CLEANING PRESTIGE CARPET CLEANING 9834 3300 CARPET SUPPLIERS BLACKTOWN CARPET CHOICE 9671 1800 CATERING LAINGY’S CATERING 0449 759 397 CATERING SUPPLIES ABCOE 4725 1230 CHEMIST COLYTON CENTRE PHARMACY 9623 8330 CONCRETING N & L MURRAY CONCRETING 0418 266 533 DISASTER RECOVERY HOSTED CONTINUITY- PROFESSIONAL CONTINUNITY 8005 5910 EGG SUPPLIES BJ EGGS 0422 949 340 ENGINEERING AITKEN ENGINEERING 9425 1332 FITNESS CENTRE VALLEY FITNESS 9623 4100 GENERAL STORE FOODWORKS ST CLAIR 9670 2500 HOME LOANS MORTGAGE CHOICE, ST MARYS 9833 8177 HORSE RACING CUCINOTTA RACING 0410 474 238 SLOYS HARNESS RACING 4651 1086 HOTEL/MOTEL BLUE CATTLE DOG TAVERN 9670 3050 INDOOR PLAY CENTRE KIDABOUT PLAYLAND 9623 2222 LANDSCAPE SUPPLIES BLACKTOWN LANDSCAPE SUPPLIES 9627 1529 LEAFLET DISTRIBUTION SUE & LES CORNWALL 9833 7230 MEAT SUPPLIES WILMEAT CUTMEATS 4736 5566 MECHANICAL REPAIRS A1 M & S MOBILE MECHANIC 0438 171 269 C & J TRANSMISSIONS 9623 9810 PAINTERS GEORGE & SON PAINTING SERVICE 0408 258 317 PEST CONTROL EMERSONS ENVIROCARE 1800 600760 PHOTOGRAPHY ALL ACTION PHOTOGRAPHY 8807 7746 PHOTO 123 4736 6161 -

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

National Coaches Conference 2018 PROGRAM 2 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 3 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018

National Coaches Conference 2018 PROGRAM 2 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 3 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Welcome 4 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Welcome Luke Ellis Head of Participation, Pathways & Game Development Welcome to the 2018 NRL National Coaching Conference, the largest coach development event on the calendar. In the room, there are coaches working with our youngest participants right through to our development pathways and elite level players. Each of you play an equally significant role in the development and future of the players in your care, on and off the field. Over the weekend, you will get the opportunity to hear from some remarkable people who have made a career out of Rugby League and sport in general. I urge you to listen, learn, contribute and enjoy each of the workshops. You will also have a fantastic opportunity to network and share your knowledge with coaches from across the nation and overseas. Coaches are the major influencer on long- term participation and enjoyment of every player involved in Rugby League. As a coach, it is our job to create a positive environment where the players can have fun, enjoy time with their friends, develop their skills, and become better people. Coaches at every level of the game, should be aiming to improve the CONFIDENCE, CHARACTER, COMPETENCE and CONNECTIONS with our players. Remember… It’s not just what you coach… It’s HOW you coach. Enjoy the weekend, Luke Ellis 5 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Andrew Voss Event MC Now referred to as a media veteran in rugby league circles, Andrew is a sport and news presenter, commentator, writer and author. -

GUESS the PLAYER NRL Edition

GUESS THE PLAYER NRL Edition Test your knowledge of NRL players with our Guess the Player card game! This is a great game for the whole team, and can be played on a video call or in person at your Footy Colours Day event. How to Play 1. The aim of the game is to collect as many NRL player cards as possible by guessing the NRL team player the quickest. 2. The designated quiz master reads one fact out to the other players. 3. For each fact read out, players gets one guess each. 4. Players must call out their own name to have their guess. 5. The player who guesses correctly first, keeps the NRL team player card. 6. At the end of the game, the player with the most NRL team player cards wins. 1. This player began his NRL career in 2018 with 1. This New Zealand-born made the move to 1. This player was born in New Zealand but grew the Brisbane Broncos Australia when he was 15 up in Sydney alongside close friend and future 2. His debut game was remarked as ‘the birth of a 2. He is one of 10 siblings Sydney Roosters player Mitchell Pearce superstar’ by Commentator Phil Gould 3. He represented the Cook Islands in international 2. Born into a successful family, his dad was the 3. He was named at prop in the 2019 Australia PM competition between 2015 and 2017 CEO of Walmart’s US division and is currently XIII side 4. He made his NRL debut for the New Zealand the chief executive of Air New Zealand 4. -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 11 May 2009 RE: Media Summary Tuesday 05 April To

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 11 May 2009 RE: Media Summary Tuesday 05 April to Monday 11 May 2009 Kearney wants to stay on: DESPITE Friday's loss to the Kangaroos, Kiwis coach Stephen Kearney has given the first hints he wants to carry on in the role beyond this year. The 36-year-old, who guided the Kiwis to World Cup glory against all odds last year, comes off contract after the Four Nations, which ends mid-November. Anzac test defeats seen as brand damage to Kiwis: NEW ZEALAND officials are concerned that the Kiwi brand is becoming damaged by one-sided Anzac test defeats, and a former NZRL chairman has called for the mid-year game to be scrapped. Senior Kiwi and Australian officials will meet in the next month to discuss plans for the year-end Four Nations tournament, but New Zealand will also want debate over the future of this game. There is no long-term contract for the match, which is agreed to on an annual basis. It was classic Benji – good and bad: After engineering – almost single-handedly – a win for the Tigers over the Knights on a recent sunny Sunday afternoon, Benji Marshall was described by astute league analyst Phil Gould as “an enigma; a mystery wrapped up in a riddle”. That same enigma was back last night at Suncorp Stadium and, perhaps more importantly, he had the extra responsibility of captaining his world champion Kiwis against a fired up Aussie side hell-bent on revenge.