Diasporic Belonging, Masculine Identity and Sports: How Rugby League Affects the Perceptions and Practices of Pasifika Peoples in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

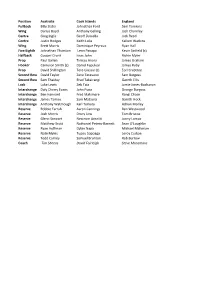

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

New Zealand Australia

30 OCT 2014 #48 30 : 12 NEW ZEALAND AUSTRALIA Martin Taupau is tackled by Corey Parker (L) and Cameron Smith (R) during the Four Nations test match between Australia and New Zealand at Suncorp Stadium, Brisbane Australia on October 25, 2014. Photo: www.photosport.co.nz. reckon I might have to knock over the next person who dismisses the 10 players too, including Jarred Waerea Hargreaves, Sam Moa, Ben Matulino, Kiwis' outstanding 30-12 win over the Kangaroos with the comment about Sam McKendry, Elijah Taylor, Konrad Hurrell, Ben Henry, Roger Tuivasa-Sheck, I how many top players the Aussies had out. Kirisome Auva'a and Sam Kasiano, so it is not we were not disadvantaged too. Let me be clear, the win was one of the best performances I have ever seen from a Kiwis It was truly magnifi cent performance and one I thoroughly enjoyed. Every player was great, outfi t, and we were great from the start. but perhaps Shaun Johnson led the way with an outstanding game, featuring terrifi c I cannot recall seeing the Aussies so fl ustered, dropping the amount of ball they did, and kicking and a wonderful solo try. I was privileged enough to watch it in Brisbane with some legends of Australian rugby The other player who stood out to me was JasonTaumalolo, the North Queensland league, and 99 percent of them agreed that the reason they were having so much trouble Cowboy. His commitment could not have been questioned, and he tackled fi ercely and was because the Kiwis were on fi re. -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 28 October 2008 RE: Media Summary Wednesday 29 October to Monday 03 November 2008 Slater takes place among the greats: AUSTRALIA 52 ENGLAND 4. Billy Slater last night elevated himself into the pantheon of great Australian fullbacks with a blistering attacking performance that left his coach and Kangaroos legend Ricky Stuart grasping for adjectives. Along with Storm teammate and fellow three-try hero Greg Inglis, Slater turned on a once-in-a-season performance to shred England to pieces and leave any challenge to Australia's superiority in tatters. It also came just six days after the birth of his first child, a baby girl named Tyla Rose. Kiwis angry at grapple tackle: The Kiwis are fuming a dangerous grapple tackle on wing Sam Perrett went unpunished in last night's World Cup rugby league match but say they won't take the issue further. Wing Sam Perrett was left lying motionless after the second tackle of the match at Skilled Park, thanks to giant Papua New Guinea prop Makali Aizue. Replays clearly showed Aizue, the Kumuls' cult hero who plays for English club Hull KR, wrapping his arm around Perrett's neck and twisting it. Kiwis flog Kumuls: New Zealand 48 Papua New Guinea NG 6. A possible hamstring injury to Kiwis dynamo Benji Marshall threatened to overshadow his side's big win over Papua New Guinea at Skilled Park last night. Arguably the last superstar left in Stephen Kearney's squad, in the absence of show-stoppers like Roy Asotasi, Frank Pritchard and Sonny Bill Williams, Marshall is widely considered the Kiwis' great white hope. -

University of Auckland Research Repository, Researchspace

Libraries and Learning Services University of Auckland Research Repository, ResearchSpace Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognize the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. Sauerkraut and Salt Water: The German-Tongan Diaspora Since 1932 Kasia Renae Cook A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German, the University of Auckland, 2017. Abstract This is a study of individuals of German-Tongan descent living around the world. Taking as its starting point the period where Germans in Tonga (2014) left off, it examines the family histories, self-conceptions of identity, and connectedness to Germany of twenty-seven individuals living in New Zealand, the United States, Europe, and Tonga, who all have German- Tongan ancestry. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 21st September 2016 Newsletter #140 By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan RIKEY DID the Vodafone Warriors get hammered at the weekend. The constant theme was that we Cneed a player clearout. That is hardly groundbreaking stuff, but what was, was that players were named. Hugh McGahan singled out Manu Vatuvei and Ben Matulino, arguing both had failed to live up their status as two of our highest paid players. The former Kiwi captain said Warriors coach Stephen Kearney could make a mark by showing the pair the door, and proving to the others that poor performances won't be tolerated. “Irrespective of his standing, Manu Vatuvei has got to go,” McGahan told Tony Veitch. “And again, irre- spective of his standing, Ben Matulino has got to go. They have underperformed. If you're going to make an impact I'd say that's probably the two players that you would look at.” Bold stuff, and fair play to the man, he told it like he saw it. Kearney, on the other hand, clearly doesn’t see it the same way, since he named both in the Kiwis train-on squad, and while he acknowledged they had struggled this year, he backed himself to get the best out of them. In fact he went further, he said it was his job. “That's my responsibility as the coach, to get the individuals in a position so they can go out and play their best. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

82 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 3 Lieutenant Peter Phipps, Wellington Division, Royal Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant George Henry Lloyd Davies, Naval Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand), appointed to Wellington Division, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve H.M.S. "Philomel" additional for duty at Navy Office, (New Zealand), appointed to H.llf.S. " Philomel " Wellington, to date 4th September, 1939. additional for temporary dnty 11,t Navy Office, Wellington, Commander Arthur Bruce Welch, Royal Naval Volunteer to date 25th August, 1939. Reserve (New Zealand) (Retired), appointed to H.M.S. Lieutenant-Commander Archibald Cornelius, Royal Naval " Philomel" additional for duty as District Intelligence Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand) (Retired), appointed Officer, Port Chalmers, to date 4th September, 1939. To to H.M.S. "Philomel" additional for temporary duty at serve as Lieutenant-Commander. Navy Office, Wellington, to date 24th August, 1939. Lieutenant-Commander Ralph Leslie Cross, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand) (Retired), appointed Commander Arthur Bruce Welch, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand) (Retired), appointed to H.M.S. to H.M.S. " Philomel" additional for Naval Control "Philomel" additional for temporary duty as District Staff duties at Wellington, to date 4th September, 1939. Intelligence Officer at Port Chalmers, to date 27th Lieutenant Bernard Theodore Giles, '\Vellington Division, August, 1939. To serve as a Lieutenant-Commander. Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand), appointed to H.M.S. " Philomel" additional for duty at Navy Lieutenant-Commander Ralph Leslie Cross, Royal Naval Office, Wellington, to date 4th September, 1939. Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand) (Retired), appointed to H.M.S. "Philomel ,. additional for temporary Naval Lieutenant 1Valter William Brackenridge, Wellington Control Staff duties at Wellington, to date 27th August, Division, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (New Zeala,nd), 1939. -

Mad Butcher Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch’s Mad Butcher Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 2015 Dick Smith NRL Auckland Nines Special Edition Newsletter Dick Smith NRL Auckland Nines Details Date: This Saturday 31st January and Sunday 1st February, 2015 Time: Saturday - Gates open: 11:30am - Event commences: 12:00pm - Gates close: 8:30pm Sunday - Gates open 10:00am - Event commences: 11:10am - Event ends: 8:30pm Venue: Eden Park, Mt Eden, Auckland Parking/Transport: There is no parking on-site. However complimentary public transport to and from Eden Park on special services is included with your ticket; just present your ticket upon boarding. For more info visit: www.AT.co.nz/info/events.aspx Please note there is only ONE ticket for BOTH days so please keep your ticket safe. Ensure everyone brings their ticket each day as it will be required for entry. Please also read the condi- tions of entry to Eden Park at www.edenpark.co.nz and rules of play that are in the newsletter. Buy tickets at www.ticketek.co.nz/nrlakl9s To ensure everyone has a great can be consumed on transport at No commercially bought food (e.g weekend, the organisers have any time. McDonalds, KFC, Burger King some rules of play that must be etc) may be brought into the ven- adhered to: If you have purchased tickets to ue, but you are welcome to bring the family zone, note that this is small amounts of non-commer- A liquor ban will be enforced in an alcohol free zone and no al- cially produced food for personal the neighbourhood surrounding cohol may be purchased or con- consumption. -

Two Kiwis on Their Way out of NRL: Kiwis Coach Stephen Kearney Is Philosophical About Two Kiwis Leaving the NRL to Pick up More Money in England

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 18 May 2009 RE: Media Summary Tuesday 12 April to Monday 18 May 2009 They are happy helping others: One helps out people from the other side of the world, one mentors the troubled kids at her league club, and another just looks after his mum. What the five winners of this year's Young Community Leaders Awards have in common, though, is a dedication to social work, rather than their social lives. Emma Daken, Teresa Edge, Henare Mihaere, Fofo Molia and Libby Tuite were chosen from nearly 60 nominees to receive the awards, which recognised Wellingtonians under the age of 25 working in the not-for- profit sector, either as a volunteer or in a paid position. Anzac test to stay - and it'll be in Brisbane: Despite the Kiwis' dire results in mid-year tests across the Tasman, the Anzac league test is likely to survive and remain in Brisbane because the New Zealand Rugby League cannot afford to host the game. NZRL chairman Ray Haffenden admits there are conflicting views about the test's value after New Zealand's run of eight successive defeats but has given it his backing and said the league cannot afford to scrap the game, nor host it. No sign of league World Cup cash: Six months since the World Cup final, the much-trumpeted tournament profit apparently still sits in a Rugby League International Federation bank account. New Zealand has not been told what the final profit is, or how it will be distributed and RLIF boss Colin Love couldn't be reached last night. -

Sir Peter Leitch | Newsletter

THE ACTION KICKS OFF THIS SATURDAY NIGHT Sir Peter Leitch Club Newsletter RLWC 2017 24th October 2017 It’s 4 days until the Kiwis play # their first game of the 2017 RLWC 193 Back The Kiwis By Enjoying Lunch By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan E ARE only days from the kick-off of the 2017 Rugby League World Cup, with Australia and England W– in what will be a hell of a match - doing the honours on Friday night. Of course the Kiwis take on Samoa on Saturday night at Mt Smart, and that one should be a good game too. League legend Olsen Filipaina is taking the ball out, which is pretty cool given he has represented the Kiwis and Samoa. The game I am looking forward to is the Kiwis v Tonga in Hamilton, because there is not going to be a lot of love lost when those two sides meet, after everything that has gone on. Before a ball is kicked I have the Kiwis lunch at the Ellerslie Events Centre to look forward to on Friday. When Pete asked if I would take it on with Gordon Gibbons and Tony Feasey, I foolishly said yes, not want- ing to let Pete down. But in truth Gordon has been amazing and we have an incredible line-up of Kiwis greats taking to the stage, and players with a long history of World Cup and test glory in attendance. I have been to several of Peter’s Kiwis lunches and enjoyed every one of them. -

Pacific Outreach Program – Tonga Program Evaluation Research Report Report Prepared for the National Rugby League (NRL) July 2017 2 Centre for Sport and Social Impact

Centre for Sport and Social Impact Pacific Outreach Program – Tonga Program Evaluation Research Report Report prepared for the National Rugby League (NRL) July 2017 2 Centre for Sport and Social Impact Acknowledgements We wish to thank the Pacific Outreach Program stakeholders, including representatives from organisations and relevant government departments in sport, education and community development contexts, who gave their time to participate in the interviews. The assistance of staff at the NRL is gratefully acknowledged. Project team Associate Professor Emma Sherry (PhD) Dr Nico Schulenkorf (PhD) Dr Emma Seal (PhD) June 2017 For further information Associate Professor Emma Sherry Centre for Sport and Social Impact La Trobe University Victoria 3086 Australia T +61 3 9479 1343 E [email protected] Pacific Outreach Program – Tonga Program Evaluation Research Report 3 Contents Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 6 1.1 The Pacific Outreach Program 6 1.2 Sport-for-Development Approaches 6 1.3 Report Outline 8 2.0 Method 9 2.1 Research Aims 9 2.2 Data Collection 9 2.3 Data Analysis 9 3.0 State of Play: Contextual Factors Influencing Sport-For-Development in Tonga 12 3.1 Macro Level Factors – Broad Context 12 3.2 Meso Level Factors – Operating Environment 13 3.3 Micro Level – Internal Operations 13 4.0 Pacific Outreach Program Progress and Stakeholder Ideas for Future Development 15 4.1 Progress Achieved 15 4.2 Areas for Development 22 5.0 Summary and Concluding Comments 30 References 33 4 Centre for Sport and Social Impact Pacific Outreach Program – Tonga Program Evaluation Research Report 5 Executive Summary Program Background: The NRL’s Pacific Outreach Program is a three-way partnership between the Australian Government (represented by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, DFAT), the Government in Tonga, and the Australian Rugby League Commission (represented by the NRL). -

The Sydney Cricket Ground: Sport and the Australian Identity

The Sydney Cricket Ground: Sport and the Australian Identity Nathan Saad Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney This paper explores the interrelationship between sport and culture in Australia and seeks to determine the extent to which sport contributes to the overall Australian identity. It uses the Syndey Cricket Ground (SCG) as a case study to demonstrate the ways in which traditional and postmodern discourses influence one’s conception of Australian identity and the role of sport in fostering identity. Stoddart (1988) for instance emphasises the utility of sports such as cricket as a vehicle through which traditional British values were inculcated into Australian society. The popularity of cricket in Australia constitutes perhaps what Markovits and Hellerman (2001) coin a “hegemonic sports culture,” and thus represents an influential component of Australian culture. However, the postmodern discourse undermines the extent to which Australian identity is based on British heritage. Gelber (2010) purports that contemporary Australian society is far less influenced by British traditions as it was prior to WWII. The influence of immigration in Australia, and the global ascendency of Asia in recent years have led to a shift in national identity, which is reflected in sport. Edwards (2009) and McNeill (2008) provide evidence that traditional constructions of Australian sport minimise the cultural significance of indigenous athletes and customs in shaping national identity. Ultimately this paper argues that the role of sport in defining Australia’s identity is relative to the discourse employed in constructing it. Introduction The influence of sport in contemporary Australian life and culture seems to eclipse mere popularity. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2019 No. 206 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, House amendment to the Senate called to order by the Honorable THOM PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, amendment), to change the enactment TILLIS, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, December 19, 2019. date. North Carolina. To the Senate: McConnell Amendment No. 1259 (to Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, Amendment No. 1258), of a perfecting f of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable THOM TILLIS, a Sen- nature. McConnell motion to refer the mes- PRAYER ator from the State of North Carolina, to perform the duties of the Chair. sage of the House on the bill to the The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- CHUCK GRASSLEY, Committee on Appropriations, with in- fered the following prayer: President pro tempore. structions, McConnell Amendment No. Let us pray. Mr. TILLIS thereupon assumed the 1260, to change the enactment date. Eternal God, You are our light and Chair as Acting President pro tempore. McConnell Amendment No. 1261 (the salvation, and we are not afraid. You instructions (Amendment No. 1260) of f protect us from danger so we do not the motion to refer), of a perfecting na- tremble. RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME ture. Mighty God, You are not intimidated The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- McConnell Amendment No. 1262 (to by the challenges that confront our Na- pore.