From Chaucer to Trevisa Exploring Language Using the Oxford English Dictionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Memorials of Old Suffolk

I \AEMORIALS OF OLD SUFFOLK ISI yiu^ ^ /'^r^ /^ , Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldsuOOreds MEMORIALS OF OLD SUFFOLK EDITED BY VINCENT B. REDSTONE. F.R.HiST.S. (Alexander Medallitt o( the Royal Hul. inK^ 1901.) At'THOB or " Sacia/ L(/* I'm Englmnd during th* Wmrt »f tk* R»ut,- " Th* Gildt »nd CkMHtrUs 0/ Suffolk,' " CiUendar 0/ Bury Wills, iJS5-'535." " Suffolk Shi^Monty, 1639-^," ttc. With many Illustrations ^ i^0-^S is. LONDON BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.G. AND DERBY 1908 {All Kifkts Rtterifed] DEDICATED TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE Sir William Brampton Gurdon K.C.M.G., M.P., L.L. PREFACE SUFFOLK has not yet found an historian. Gage published the only complete history of a Sufifolk Hundred; Suckling's useful volumes lack completeness. There are several manuscript collections towards a History of Suffolk—the labours of Davy, Jermyn, and others. Local historians find these compilations extremely useful ; and, therefore, owing to the mass of material which they contain, all other sources of information are neglected. The Records of Suffolk, by Dr. W. A. Copinger shews what remains to be done. The papers of this volume of the Memorial Series have been selected with the special purpose of bringing to public notice the many deeply interesting memorials of the past which exist throughout the county; and, further, they are published with the view of placing before the notice of local writers the results of original research. For over six hundred years Suffolk stood second only to Middlesex in importance ; it was populous, it abounded in industries and manufactures, and was the home of great statesmen. -

Handbook of Simplified Spelling

891 seia Kan. HANDBOOK OF SIMPLIFIED SPELLING UC-NRLF r5 SIMPLIFIED SPELLING BOARD fe NEW YORK 1920 GIFT OF -N '-H 1 V. v- C". f- n V HANDBOOK OF SIMPLIFIED SPELLING Written and Compiled under the Direction of the Filology Committee of the Simplified Spelling J3oard CHARLES H. GRANDGENT, L.H.D., CALVIN THOMAS, LL.D. ' by HENRY GALLUP PAINE, A.B., Secretary of the Board NEW YORK 192C Copyright, 1920, .617 SIMPLIFIED SPELLING BOARD 1 Madison avenue New York r CONTENTS PART L English Spelling and the Movement to Improve It Page Spelling Difficulties 1 Early Spelling Reformers 4 19th Century Spelling Reformers 9 Simplified Spelling Board Organized 15 Statement of Principles 18 Report of Progress 20 Membership of Board 29 PART 2. The Case for Simplified Spelling Page Introduction 1 Reasons for Simplifying 1 Ansers to Objections 25 PART 3. Rules and Dictionary List Page Introduction 1 Rules for Simplified Spelling 5 Dictionary List 11 M203879 "It is the generations of children to come who appeal to us to save them from the affliction which we have endured and forgotten." WILLIAM DWIGHT WHITNEY. HANDBOOK OF SIMPLIFIED SPELLING PART 1 ENGLISH SPELLING AND THE MOVEMENT TO IMPROVE IT Spelling, Its True Function Spelling was invented by man and, like other human inventions, is capable of development and improve- ment by man in the direction of simplicity, economy, and efficiency. Its true function is to represent as accurately as possible by means of simbols (letters) the sounds of the spoken (i. e. the living) language, and thus incidentally to record its history. -

A DOCUMENTARY ACCOUNT of the Foundation of the British Academy

A DOCUMENTARY ACCOUNT OF The Foundation of the British Academy 1 Letter sent by the Secretaries of the Royal Society to certain ‘distinguished men of letters’, 21 November 1899 The Royal Society Burlington House, W. November 21, 1899 Sir, We are directed by the President and Council of the Royal Society to inform you that a project for the foundation of an International Association of Academies has been under consideration for some time. A preliminary gathering of representatives of the principal Academies of the world was held at Wiesbaden in the autumn of the present year [October 1899]. The enclosed “Proposed Statutes of Constitution and Procedure” will inform you as to the resolutions adopted. It is probable that the first formal meeting of the Association will be held in Paris in 1900, and that the resolutions of the Wiesbaden Conference will then be formally accepted as the basis of the constitution of the Association. Until the meeting took place at Wiesbaden, it was uncertain whether the Association would be formed of Scientific Academies only; but, as you will see, it was decided to form two sections, the one devoted to Natural Science, and the other to Literature, Antiquities and Philosophy. Although the conditions which Academies claiming admission must fulfil were not formally defined, it is understood (1) that no Society devoted to one subject or to a small range of subjects will be regarded as an “Academy”, and (2) that, as a rule, only one Academy will be admitted from each country to the literary and scientific sections respectively. So far as we are aware, there is no Society in England dealing with subjects embraced by the “Literary” Section which satisfies the first of these conditions. -

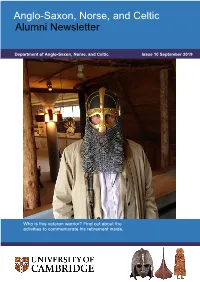

ASNC Alumni Newsletter

Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic Alumni Newsletter Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic Issue 10 September 2019 Who is this veteran warrior? Find out about the activities to commemorate his retirement inside. A Message from the Head of Department 2 Hwæt! once again, and welcome to this year’s Alumni Newsletter. As ever, there’s been plenty going on this year in the Department, and for ASNCs everywhere. This academic year, we are thrilled to be saying hello to not one but two new lecturers to the Department. As of 1 September, Erik Niblaeus has joined us (from Durham) to become our brand new lecturer in manuscript studies, and Rory Naismith (from King’s College London) to look after the History of England before the Norman Conquest. The very warmest of welcomes to them both. Elsewhere in this issue we bid a very fond fare- well to Simon Keynes, who is retiring after twenty years as the Elrington and Bosworth Professor, and forty-one years altogether as a lecturer in the Department. We are delighted that Simon is succeeded in the Chair by our very own Rosalind Love, who will occupy it with the very greatest distinction. The ASNC named lectures this year were very much brought to you by the letter ‘J’ — as leading scholars Jayne Carroll (Nottingham), Judith Jesch (Nottingham) and Jacopo Bisagni (NUI, Galway) gave the Quiggin, Chadwick and Hughes lectures respectively. We thank them for deliver- ing such memorable and brilliant accounts of ‘watery place-names and the medieval English landscape’, ‘the poetry of Orkneyinga saga’ and ‘the Irish tradition of the divisions of time in the early Middle Ages’. -

University of York

TEXT AND IMAGE IN LATE MEDIAEVAL ENGLISH VERNACULARLITERARY MANUSCRIPTS FOUR VOLUMES VOLUME TWO Lesley Suzanne Lawton D. Phil. University of York ENGLISH November 1982 CONTENTS Volume 2 Appendix Appendix 2 24 Footnotes Introduction 39 Chapter 1 39 Chapter 2 51 Chapter 3 72 Chapter 4 91 Chapter 5 100 Chapter 6 109 Bibliography 127 i APPENDIX 1 In this appendix I. correlate the occurrence of champ Initials in eleven Troy Book manuscripts and woodcuts in Pynson's print of the text to demonstrate the degree of agreement involved in their placement. The manuscripts are arranged in the order in which they appear in Bergen, using his abbreviation. In K the Lydgate text-begins at 1.1689 and ends at IV 5337, the remainder being supplied from Barbour's version. In H1 the text begins at 13444 and spaces only are left for champ initials which were never completed. Cr. shows the major difference in layout: on every page where a miniature occurs, there is a blue or pink initial on a gold ground. attached to a border; on other pages there are gold initials on a blue and red ground with champ sprays. Thus a hierarchy is indicated, the more important section of the text being associated with a miniature. Pynson's print (Py. ) also suggests a hierarchy by means of chapter-headings and associated woodcuts, as opposed to other areas of the text indicated by large, sometimes decorative, initials. 5 mboIs Miniatures with borders in Cr.; woodcuts in Py.; champ initials in other manuscripts Champ initials in Cr.; decorative initials in Py. -

With an Enlarged Glossary of Cornish Provincial Words

Q)ijouA. aO?. GLOSSARY CORNISH DIALECT, &c. THE AKCIEKT LANGUAGE, AND THE DIALECT OF CORNWALL, WITH AN EXLAKGED GLOSSARY OF CORNISH PROVINCIAL WORDS. ALSO AN APPENDIX, CONTAINING A LIST OF WRITERS ON CORNISH DIALECT, AND ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ABOUT DOLLY PENTREATH, THE LAST KNOWN PERSON WHO SPOKE THE ANCIENT CORNISH AS HER MOTHER TONGUE. BY FRED. W. P. JAGO, M.B. Lond. TEURO : NETHERTON & WORTH, LEMON STREET, 1882. DEDICATION. Loving his native County, its words, and its ways, the writer, with great respect, dedicates this little book to CONTENTS. 1. Frontispiece—Portrait of Dolly Pentreatli, and sketch of her Cottage at Mousehole. 2. The Decline of the Ancient Cornish Language - - 1 3. The Eemains of the Ancient Cornish Language • 17 4. The Preface to WiUiams's Cornish Dictionary - - 29 5. Specimens of the Ancient Cornish Language - - 34 6. The Provincial Dialect of Cornwall .... 45 7. Specimens of the Cornish Provincial Dialect - - 65 8. Words in the Cornish Dialect compared with those found in the writings of Chaucer 73 9. Common English words in the Cornish Dialect, with Tables of them 94 10. On the Glossary of Cornish Provincial "W ords - - 101 11. The Glossary of Cornish Provincial Words - - 102 12. Addenda to Glossary 317 13. Curious Spelling of the Names of Drugs, li'c. - - 325 14. Explanation of the Eeferences in the Glossary - - 827 15. Appendix—DoWy Pentreath . - - - 330 16. Names of Writers on Cornish Dialect, &c. - - 842 PREFACE. Long-descended from Cornishmen, the writer, like others of his countrymen, has a clannish fondness for Cornish words and phrases. From May 1879 to October 1880, the compiler of this book wrote lists of Cornish Provincial Words, which, through the courtesy of the Editor of the " Cornishman," (published at Penzance), were then allowed to appear in that paper. -

Re-Examining the Female Voice in Chaucer's Italian-Sourced Works: a Study in Paleography, Textual Transmission, and Masculinity

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Re-Examining the Female Voice in Chaucer's Italian-Sourced Works: A Study in Paleography, Textual Transmission, and Masculinity Stacee Bucciarelli Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Bucciarelli, Stacee, "Re-Examining the Female Voice in Chaucer's Italian-Sourced Works: A Study in Paleography, Textual Transmission, and Masculinity" (2014). Dissertations. 1252. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1252 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2014 Stacee Bucciarelli LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO RE-EXAMINING THE FEMALE VOICE IN CHAUCER’S ITALIAN-SOURCED WORKS: A STUDY IN PALEOGRAPHY, TEXTUAL TRANSMISSION, AND MASCULINITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY STACEE M. BUCCIARELLI CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2014 Copyright by Stacee M. Bucciarelli, 2014 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all of the people who made this dissertation possible, starting with my exceptional professors in the English Department at Loyola University Chicago. First and foremost I would like to thank my director, Dr. Edward Wheatley, who has been an inspiration to me from the moment I began my progam. -

English Pronunciation Through the Ages

English Pronunciation through the Ages Raymond Hickey, WS 2019/20 Department of Anglophone Studies University of Duisburg and Ess1en Pronunciation -what it is and how we acquire it - 2 The goal of this seminar is to introduce students to the history of English pronunciation both in the Britain Isles (England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland) and around the world since the colonial period (after 1600). The way one pronounces one’s native variety of a language is a quintessential part of one’s identity and hence the examination of how varieties are spoken is key to our understanding of speakers’linguistic behaviour. 3 How and what we say Most of the time when we speak we think not of how to say something (e.g. pronounce the words or arrange a sentence) but rather of what we want to say (the meaning of an utterance). 4 What we can understand Within our native language we have an extraordinary ability to grasp what is being said to us or around us. We can understand men and women, children and adults, speakers of our own variety of language and those of different dialects. We can furthermore adjust for tone of voice and rate of delivery, all of this in real time while effortlessly following the meaning of what is being said. 5 When speaking we make unconscious decisions about how to pronounce sounds 6 7 8 Variation in Pronunciation There are very slight differences in the way in which speakers pronounce their language. The differences merge into each other across time and space. -

76 Literary Studies and the Academy David Goldie in 1885 the University

Literary Studies and the Academy David Goldie In 1885 the University of Oxford invited applications for the newly-created Merton Professorship of English Language and Literature. The holder of the chair was, according to the statutes, to ‘lecture and give instruction on the broad history and criticism of English Language and Literature, and on the works of approved English authors’. This was not in itself a particularly innovatory move, as the study of English vernacular literature had played some part in higher education in Britain for over a century. Oxford university had put English as a subject into its pass degree in 1873, had been participating since 1878 in Extension teaching, of which literary study formed a significant part, and had since 1881 been setting special examinations in the subject for its non-graduating women students. What was new was the fact that this ancient university appeared to be on the verge of granting the solid academic legitimacy of an established chair to an institutionally marginal and often contentious intellectual pursuit, acknowledging the study of literary texts in English to be a fit subject not just for women and the educationally disadvantaged but also for university men. English Studies had earned some respectability through the work of various educational establishments in the years leading up to this, but now, it seemed, it was about to be embraced by the Academy – an impression recently confirmed by England’s other ancient university, Cambridge, which had incorporated English as a subject in its Board for Medieval and Modern Languages in 1878. Several well-qualified literary scholars recognized the significance and prestige attached to this development by putting themselves forward for the Oxford chair, among 76 them A. -

Introduction to Bibliography

INTRODUCTION TO BIBLIOGRAPHY Seminar Syllabus G. THOMAS TANSELLE ! Syllabus for English/Comparative Literature G4010 Columbia University ! Charlottesville B O O K A R T S P R E S S University of Virginia 2002 This page is from a document available in full at http://www.rarebookschool.org/tanselle/ Nineteenth revision, 2002 Copyright © 2002 by G. Thomas Tanselle Copies of this syllabus are available for $25 postpaid from: Book Arts Press Box 400103, University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22904-4103 Telephone 434-924-8851 C Fax 434-924-8824 Email <[email protected]> C Website <www.rarebookschool.org> Copies of a companion booklet, Introduction to Scholarly Editing: Seminar Syllabus, are available for $20 from the same address. This page is from a document available in full at http://www.rarebookschool.org/tanselle/ CONTENTS Preface • 10 Part 1. The Scope and History of Bibliography and Allied Fields • 13-100 Part 2. Bibliographical Reference Works and Journals • 101-25 Part 3. Printing and Publishing History • 127-66 Part 4. Descriptive Bibliography • 167-80 Part 5. Paper • 181-93 Part 6. Typography, Ink, and Book Design • 195-224 Part 7. Illustration • 225-36 Part 8. Binding • 237-53 Part 9. Analytical Bibliography • 255-365 Subject Index • 367-70 A more detailed outline of the contents is provided on the next six pages. This page is from a document available in full at http://www.rarebookschool.org/tanselle/ 4 Tanselle: Introduction to Bibliography (2002) OUTLINE OF CONTENTS 1. The Scope and History of Bibliography and Allied Fields A. Selected Basic Readings (pages 13-14) B. -

Viking Identities and Ethnic Boundaries in England and Normandy, C.950 – C.1015

1 Enemy and Ancestor: Viking Identities and Ethnic Boundaries in England and Normandy, c.950 – c.1015 Katherine Clare Cross UCL Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 I, Katherine Cross, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed 3 Abstract This thesis is a comparison of ethnicity in Viking Age England and Normandy. It focuses on the period c.950-c.1015, which begins several generations after the initial Scandinavian settlements in both regions. The comparative approach enables an investigation into how and why the two societies’ inhabitants differed in their perceptions of viking heritage and its impact on ethnic relations in this period. Written sources provide the key to these perceptions: genealogies, histories, hagiographies, charters and law codes. The thesis is the first study to juxtapose and compare these sources and aspects of Viking Age England and Normandy. The approach to ethnicity is informed by the social sciences, especially Fredrik Barth’s Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. The emphasis here is on ethnic identity as a social construct and as a product of belief in group membership. In particular, this investigation treats ethnic identity separately from cultural markers such as names, dress, appearance, and art. In doing so, it presents a new perspective in discussions of assimilation after Scandinavian settlement. For the purpose of analysis, ‘ethnicity’ has been divided into three strands: genealogical, historical and geographical identity. Sources from England and Normandy are compared within each of the three strands.