William A. Brady: Theatre Entrepreneur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BROADSIDE 5,000 Negatives; And, Over 200 Original De Hand in His Own Car to Mill Valley

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 9, Number 4 Spring 1982 New Series SAVE AMERICA'S PERFORMING ASTRITLA IN PROVIDENCE ARTS RESOURCES! The TLA Annual Program Meeting, held The Theatre Library Association will in conjunction with the 1982 ASTR Con- present a Conference on Preservation ference to be held at Brown University, Management in Performing Arts Collec- November 19-21, is being organized by tions in Washington, D.C., April 28-May 1, Martha Mahard, Assistant Curator, The- 1982. With the assistance of the Conserva- atre Collection, Harvard University. She tion Center for Art and Historic Artifacts, FREEDLEYITLA AWARDS plans a program appropriate to the confer- the Theatre Library Association has de- ence theme, Nineteenth Century Theatre. vised a program tailored for the special Nominations have been invited for the Your suggestions are welcome. preservation problems of performing arts 1981 George Freedley Award and The The Several exhibits will be on view during collections in libraries, museums, histor- atre Library Association Award to be pre- the conference. The John Hay Library will ical societies, media centers, and perform- sented by the Association on Monday, mount an exhibit on American Drama Dur- ing arts companies. May 24, in the Vincent Astor Gallery, The ing and About the Civil War The Museum Utilizing case studies from the field, New York Public Library at Lincoln Center. of Art of the Rhode Island School of De- consultants will specify preservation tech- The George Freedley Award, established sign will mount a special exhibit on japan- niques and management options for the In 1968, in memory of the late theatre his- ese Theatre from their extensive Oriental contents of mixed-media collections: torian, critic, author, and first curator of Collection. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

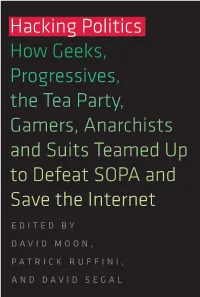

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

Signed, Sealed and Delivered: ''Big Tobacco'' in Hollywood, 1927–1951

Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2008.025445 on 25 September 2008. Downloaded from Research paper Signed, sealed and delivered: ‘‘big tobacco’’ in Hollywood, 1927–1951 K L Lum,1 J R Polansky,2 R K Jackler,3 S A Glantz4 1 Center for Tobacco Control ABSTRACT experts call for the film industry to eliminate Research and Education, Objective: Smoking in movies is associated with smoking from future movies accessible to youth,6 University of California, San Francisco, California, USA; adolescent and young adult smoking initiation. Public defenders of the status quo argue that smoking has 10 2 Onbeyond LLC, Fairfax, health efforts to eliminate smoking from films accessible been prominent on screen since the silent film era California, USA; 3 Department of to youth have been countered by defenders of the status and that tobacco imagery is integral to the artistry Otolaryngology – Head & Neck quo, who associate tobacco imagery in ‘‘classic’’ movies of American film, citing ‘‘classic’’ smoking scenes Surgery, Stanford University with artistry and nostalgia. The present work explores the in such films as Casablanca (1942) and Now, School of Medicine, Stanford, 11–13 California, USA; 4 Center for mutually beneficial commercial collaborations between Voyager (1942). This argument does not con- Tobacco Control Research and the tobacco companies and major motion picture studios sider the possible effects of commercial relation- Education and Department of from the late 1920s through the 1940s. ships between the motion picture and tobacco Medicine, -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, Collector. Theatrical

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, collector. Theatrical memorabilia, 1770-1940. 15 linear ft. (ca. 12,800 items in 32 boxes). Biography: Proprietor of Rare Old Programs, Newtonville, Mass. Summary: Theatrical memorabilia such as programs, playbills, photographs, engravings, and prints. Although there are some playbills as early as 1770, most of the material is from the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to plays there is some material relating to concerts, operettas, musical comedies, musical revues, and movies. The majority of the collection centers around Shakespeare. Included with an unbound copy of each play (The Edinburgh Shakespeare Folio Edition) there are portraits, engravings, and photographs of actors in their roles; playbills; programs; cast lists; other types of illustrative material; reviews of various productions; and other printed material. Such well known names as George Arliss, Sarah Bernhardt, the Booths, John Drew, the Barrymores, and William Gillette are included in this collection. Organization: Arranged. Finding aids: Contents list, 19p. Restrictions on use: Collection is shelved offsite and requires 48 hours for access. Available for faculty, students, and researchers engaged in scholarly or publication projects. Permission to publish materials must be obtained in writing from the Librarian for Rare Books and Manuscripts. 1. Arliss, George, 1868-1946. 2. Bernhardt, Sarah, 1844-1923. 3. Booth, Edwin, 1833-1893. 4. Booth, John Wilkes, 1838-1865. 5. Booth, Junius Brutus, 1796-1852. 6. Drew, John, 1827-1862. 7. Drew, John, 1853-1927. 8. Barrymore, Lionel, 1878-1954. 9. Barrymore, Ethel, 1879-1959. 10. Barrymore, Georgiana Drew, 1856- 1893. 11. Barrymore, John, 1882-1942. 12. Barrymore, Maurice, 1848-1904. -

John Gassner

John Gassner: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Gassner, John, 1903-1967 Title: John Gassner Papers Dates: 1894-1983 (bulk 1950-1967), undated Extent: 151 document boxes, 3 oversize boxes (65.51 linear feet), 22 galley folders (gf), 2 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The papers of the Hungarian-born American theatre historian, critic, educator, and anthologist John Gassner contain manuscripts for numerous works, extensive correspondence, career and personal papers, research materials, and works by others, forming a notable record of Gassner’s contributions to theatre history. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-54109 Language: Chiefly English, with materials also in Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gifts, 1965-1986 (R2803, R3806, R6629, G436, G1774, G2780) Processed by: Joan Sibley and Amanda Reyes, 2017 Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, which provided funds to support the processing and cataloging of this collection. Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Gassner, John, 1903-1967 Manuscript Collection MS-54109 Biographical Sketch John Gassner was a noted theatre critic, writer, and editor, a respected anthologist, and an esteemed professor of drama. He was born Jeno Waldhorn Gassner on January 30, 1903, in Máramarossziget, Hungary, and his family emigrated to the United States in 1911. He showed an early interest in theatre, appearing in a school production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in 1915. Gassner attended Dewitt Clinton High School in New York City and was a supporter of socialism during this era. -

Between the Covers Rare Books a Conversation Between Tom And

A short list of interesting selections from our inventory. View this email in your browser Between The Covers Rare Books illustration by Tom Bloom A conversation between Tom and Ashley: A: [holds skulls] To list or not to list…that is the question. T: This doesn’t look like work… A: I’m honing my thespian skills for my new drama e-list. T: Less honing, more working. A: The common people never understand real artists. T: [points to desk] “Act” like a bookseller. A: OK. Cocktail, please. T: [walks away] A: Alas, poor Thomas, I knew him well. -end scene- eCatalog 41: Drama 1. (Anthology) The Best Plays 1936-1937 and the Year Book of the Drama in America New York: Dodd, Mead & Company 1937 $85 First edition. Edited by Burns Mantle, and Inscribed by Mantle: "To Shannon – Stout fella – Affectionately, Burns Mantle. 1937." Read More 2. Edward ALBEE Three Tall Women New York: Dutton (1995) $100 First edition. Slip of paper laid in with an Inscription by Albee. Read More 3. Michael BENTHALL and Ralph Nelson William Shakespeare Hamlet: A Television Script [No place]: CBS Television Network, (1959): CBS Television Network (1959) $45 First edition thus. Profusely illustrated in black and white by Ben Shahn. Read More 4. Lawrence FERLINGHETTI Unfair Arguments with Existence: Seven Plays for a New Theatre (New York): New Directions (1963) $40 First edition. Paperback original. Read More 5. Graham GREENE British Dramatists London: William Collins 1942 $100 First edition. Read More 6. Oscar HAMMERSTEIN II Program for: Carmen Jones New York: Program Publishing Co. -

South Pacific

THE MUSICO-DRAMATIC EVOLUTION OF RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN’S SOUTH PACIFIC DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James A. Lovensheimer, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Arved Ashby, Adviser Professor Charles M. Atkinson ________________________ Adviser Professor Lois Rosow School of Music Graduate Program ABSTRACT Since its opening in 1949, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Pulitzer Prize- winning musical South Pacific has been regarded as a masterpiece of the genre. Frequently revived, filmed for commercial release in 1958, and filmed again for television in 2000, it has reached audiences in the millions. It is based on selected stories from James A. Michener’s book, Tales of the South Pacific, also a Pulitzer Prize winner; the plots of these stories, and the musical, explore ethnic and cutural prejudice, a theme whose treatment underwent changes during the musical’s evolution. This study concerns the musico-dramatic evolution of South Pacific, a previously unexplored process revealing the collaborative interaction of two masters at the peak of their creative powers. It also demonstrates the authors’ gradual softening of the show’s social commentary. The structural changes, observable through sketches found in the papers of Rodgers and Hammerstein, show how the team developed their characterizations through musical styles, making changes that often indicate changes in characters’ psychological states; they also reveal changing approaches to the musicalization of the novel. Studying these changes provides intimate and, occasionally, unexpected insights into Rodgers and Hammerstein’s creative methods. -

National Arena

I-. Broadway: A Critic Looks Back Lavery Drama, Hartman Revue Atkinson’s Scrapbook Recalls Dozen Years Coming Up By tht Associated Press of An Amusing Analytic Mind Emmett Lavery is the author of a new play premiering on Broad- By Jay Carmody way Tuesday evening at the Mans- One of the challenges flung to drama critics by persons who would field Theater. A revue, starring the Hartmans, much prefer flinging the critics over cliffs is: Why don’t you write fashionable comedy ballroom danc- something better? ing team, is the week's other hope- Some day in reply to this query, a modest, reticent little man in ful arrival. the drama reviewing trade will reach into his inner coat pocket and “The"Gentleman From Athens" is pull out a long list of titles which prove this already has been done. the name of Lavery’s drama, the He will start, perhaps, with Shaw’s “Critical Opinions and Essays,” action of which takes place in where the two volumes which have retained their popularity for half a century Washington, gentleman of the title is a member of Con- and which deal, in large part, with plays which otherwise would have gress. Sam Wanamaker is the di- been dead an interval. equal rector, Ralph Alswang is the de- There Are Dozens Such Books. signer, Martin Gosch is producing, He will go on from there to half a dozen titles by Max Beerbohm, in association with Eunice Healey. The cast includes a dozen and one half by George Jean Nathan, a handful by John Anthony Quinn, Edith Atwater, Alan Hewlitt, Feodor Mason Brown, Burns Mantle and a number of others. -

1920 Patricia Ann Mather AB, University

THE THEATRICAL HISTORY OF WICHITA, KANSAS ' I 1872 - 1920 by Patricia Ann Mather A.B., University __of Wichita, 1945 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charf;& Redacted Signature Sept ember, 19 50 'For tne department PREFACE In the following thesis the author has attempted to give a general,. and when deemed.essential, a specific picture of the theatre in early day Wichita. By "theatre" is meant a.11 that passed for stage entertainment in the halls and shm1 houses in the city• s infancy, principally during the 70' s and 80 1 s when the city was still very young,: up to the hey-day of the legitimate theatre which reached. its peak in the 90' s and the first ~ decade of the new century. The author has not only tried to give an over- all picture of the theatre in early day Wichita, but has attempted to show that the plays presented in the theatres of Wichita were representative of the plays and stage performances throughout the country. The years included in the research were from 1872 to 1920. There were several factors which governed the choice of these dates. First, in 1872 the city was incorporated, and in that year the first edition of the Wichita Eagle was printed. Second, after 1920 a great change began taking place in the-theatre. There were various reasons for this change.