An Introduction to the Epiphytic Orchids of East Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyonia 8(1) 2005

Lyonia 8(1) 2005 Volume 8(1) July 2005 ISSN: 0888-9619 Introduction Lyonia, Volume 8(1), July 2005 Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Rainer Bussmann Contact Information Surface mail: Lyonia Harold L. Lyon Arboretum 3860 Manoa Rd.Honolulu, HI 98622 USA Phone: +1 808 988 0456 e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Balslev, Henrik, University of Aarhus, Denmark Brandt, Kirsten, Denmark Bush, Marc, Florida Institure of Technology, USA Cleef, Antoine, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands Cotton, Elvira, University of Aarhus, Denmark Goldarazena, Arturo, NEIKER, Spain Geldenhuys, Coert, FORESTWOOD, South Africa Goikoetxea, Pablo G., NEIKER, Spain Gradstein, Rob, University of Goettingen, Germany Gunderson, Lance, Emory University, USA Hall, John B., University of Bangor, United Kingdom Janovec, John, BRIT, USA Joergensen, Peter, Missouri Botanical Garden, USA Kilpatrick, Alan, San Diego State University, USA Kueppers, Manfred, University of Hohenheim, Germany Lovett, Jon C., University of York, United Kingdom Lucero Mosquera, Hernan P., Universidad Tecnica Particular Loja, Ecuador Matsinos, Yiannis G., University of the Aegean, Greece Miller, Marc, Emory University, USA Navarete Zambrano, Hugo G., Pontifica Universidad Catholica Quito, Ecuador Onyango, John C., Maseno University, Kenya Pritchard, Lowell, Emory University, USA Pitman, Nigel, Duke University, USA Pohle, Perdita, University of Giessen, Germany Poteete, Amy R., University of New Orleans, USA Sarmiento, Fausto, University of Georgia, USA Sharon, Douglas, University of California -

Licuati Forest Reserve, Mozambique: Flora, Utilization and Conservation

LICUATI FOREST RESERVE, MOZAMBIQUE: FLORA, UTILIZATION AND CONSERVATION by Samira Aly Izidine Research Project Report submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the taught degree Magister Scientiae (Systematics and Conservation Evaluation) in the Faculty of Natural & Agricultural Sciences Department of Botany (with Department of Zoology & Entomology) University of Pretoria Pretoria Supervisor: Prof. Dr. A.E.van Wyk May 2003 © University of Pretoria Digitised by the Open Scholarship & Digitisation Programme, University of Pretoria, 2016. I LICUATI FOREST RESERVE, MOZAMBIQUE: FLORA, UTILIZATION AND CONSERVATION Samira Aly lzidine 2003 © University of Pretoria Digitised by the Open Scholarship & Digitisation Programme, University of Pretoria, 2016. To the glory of God and to the memory of my dear father, Aly Abdul Azize Izidine, 6-11-1927 - 7-03-2003 A gl6ria de Deus e em memoria ao meu querido pai, Aly Abdul Azize Izidine, 6-11-1927 - 7-03-2003 © University of Pretoria Digitised by the Open Scholarship & Digitisation Programme, University of Pretoria, 2016. TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION .................................................................................................. i LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES .............................................................. iv LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES ............................................................... v ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................... 1 PROJECT PROPOSAL .................................................................................. -

Nitrogen Containing Volatile Organic Compounds

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Nitrogen containing Volatile Organic Compounds Verfasserin Olena Bigler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Pharmazie (Mag.pharm.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 996 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Pharmazie Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer Danksagung Vor allem lieben herzlichen Dank an meinen gütigen, optimistischen, nicht-aus-der-Ruhe-zu-bringenden Betreuer Herrn Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer ohne dessen freundlichen, fundierten Hinweisen und Ratschlägen diese Arbeit wohl niemals in der vorliegenden Form zustande gekommen wäre. Nochmals Danke, Danke, Danke. Weiteres danke ich meinen Eltern, die sich alles vom Munde abgespart haben, um mir dieses Studium der Pharmazie erst zu ermöglichen, und deren unerschütterlicher Glaube an die Fähigkeiten ihrer Tochter, mich auch dann weitermachen ließ, wenn ich mal alles hinschmeissen wollte. Auch meiner Schwester Ira gebührt Dank, auch sie war mir immer eine Stütze und Hilfe, und immer war sie da, für einen guten Rat und ein offenes Ohr. Dank auch an meinen Sohn Igor, der mit viel Verständnis akzeptierte, dass in dieser Zeit meine Prioritäten an meiner Diplomarbeit waren, und mein Zeitbudget auch für ihn eingeschränkt war. Schliesslich last, but not least - Dank auch an meinen Mann Joseph, der mich auch dann ertragen hat, wenn ich eigentlich unerträglich war. 2 Abstract This review presents a general analysis of the scienthr information about nitrogen containing volatile organic compounds (N-VOC’s) in plants. -

CITES Orchid Checklist Volumes 1, 2 & 3 Combined

CITES Orchid Checklist Online Version Volumes 1, 2 & 3 Combined (three volumes merged together as pdf files) Available at http://www.rbgkew.org.uk/data/cites.html Important: Please read the Introduction before reading this Part Introduction - OrchidIntro.pdf Part I : All names in current use - OrchidPartI.pdf Part II: Accepted names in current use - OrchidPartII.pdf (this file) - please read the introduction file first Part III: Country Checklist - OrchidPartIII.pdf For the genera: Aerangis, Angraecum, Ascocentrum, Bletilla, Brassavola, Calanthe, Catasetum, Cattleya, Constantia, Cymbidium, Cypripedium, Dendrobium (selected sections only), Disa, Dracula, Encyclia, Laelia, Miltonia, Miltonioides, Miltoniopsis, Paphiopedilum, Paraphalaenopsis, Phalaenopsis, Phragmipedium, Pleione, Renanthera, Renantherella, Rhynchostylis, Rossioglossum, Sophronitella, Sophronitis Vanda and Vandopsis Compiled by: Jacqueline A Roberts, Lee R Allman, Sharon Anuku, Clive R Beale, Johanna C Benseler, Joanne Burdon, Richard W Butter, Kevin R Crook, Paul Mathew, H Noel McGough, Andrew Newman & Daniela C Zappi Assisted by a selected international panel of orchid experts Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Copyright 2002 The Trustees of The Royal Botanic Gardens Kew CITES Secretariat Printed volumes: Volume 1 first published in 1995 - Volume 1: ISBN 0 947643 87 7 Volume 2 first published in 1997 - Volume 2: ISBN 1 900347 34 2 Volume 3 first published in 2001 - Volume 3: ISBN 1 84246 033 1 General editor of series: Jacqueline A Roberts 2 Part II: Accepted Names / Noms Reconnu -

Orchids Limited Catalog

2003-2004 Orchids Limited Catalog Hic Natus Ubique Notus (Born here, known everywhere!) 25 years ago, in 1978, Orchids Limited started in a very small greenhouse behind a plant store in Minnetonka, Minnesota. Now located in Plymouth, we have grown to five greenhouses, a lab and support building. Our goal has always been to provide high quality species and hybrids in a niche market. We continue to breed new varieties and raise large populations of species derived from select stock. We are now seeing the fruits of our labor with many new exciting hybrids. It is very satisfying to see populations of species that were once hard to obtain or produce, now become available through our laboratory. Thanks to all of our customers, past and present, who have supported us and enabled us to grow. Please visit our web site at www.orchidweb.com for the most up-to-date offerings. We have designed a custom search engine to allow you to search for plants by name, category, color, temperature, bloom season or price range. Or, simply click "Browse our entire selection" for an alphabetic listing of all items. Our In Spike Now section, updated weekly, lists all the plants in flower or bud that are ready to be shipped. The Plant of the Week feature and Plant of the Week Library provide pictures and detailed cultural information on numerous species and hybrids. Thank you for choosing Orchids Limited. Orchids Limited 4630 Fernbrook Lane N. Plymouth, MN 55446 U.S.A. www.orchidweb.com Toll free: 1-800-669-6006 Phone: 763-559-6425 Fax: 763-557-6956 e-mail: [email protected] Nursery Hours: Mon-Sat 9:00 a.m. -

Phylogenetic Placement of the Enigmatic Orchid Genera Thaia and Tangtsinia: Evidence from Molecular and Morphological Characters

TAXON 61 (1) • February 2012: 45–54 Xiang & al. • Phylogenetic placement of Thaia and Tangtsinia Phylogenetic placement of the enigmatic orchid genera Thaia and Tangtsinia: Evidence from molecular and morphological characters Xiao-Guo Xiang,1 De-Zhu Li,2 Wei-Tao Jin,1 Hai-Lang Zhou,1 Jian-Wu Li3 & Xiao-Hua Jin1 1 Herbarium & State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, P.R. China 2 Key Laboratory of Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650204, P.R. China 3 Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun Township, Mengla County, Yunnan province 666303, P.R. China Author for correspondence: Xiao-Hua Jin, [email protected] Abstract The phylogenetic position of two enigmatic Asian orchid genera, Thaia and Tangtsinia, were inferred from molecular data and morphological evidence. An analysis of combined plastid data (rbcL + matK + psaB) using Bayesian and parsimony methods revealed that Thaia is a sister group to the higher epidendroids, and tribe Neottieae is polyphyletic unless Thaia is removed. Morphological evidence, such as plicate leaves and corms, the structure of the gynostemium and the micromorphol- ogy of pollinia, also indicates that Thaia should be excluded from Neottieae. Thaieae, a new tribe, is therefore tentatively established. Using Bayesian and parsimony methods, analyses of combined plastid and nuclear datasets (rbcL, matK, psaB, trnL-F, ITS, Xdh) confirmed that the monotypic genus Tangtsinia was nested within and is synonymous with the genus Cepha- lanthera, in which an apical stigma has evolved independently at least twice. -

Aerangis Articulata by Brenda Oviatt and Bill Nerison an Exquisite Star from Madagascar

COLLECTor’s item by Brenda Oviatt and Bill Nerison Aerangis articulata An Exquisite Star from Madagascar IN ALL HONESTY, WHEN WE FOUND out that our photo of Aerangis articulata was chosen for the cover of Isobyl la Croix’s (2014) new book Aerangis, we were more than just a little excited! We decided that this is a perfect opportunity to tell people more about Aergs. articulata and give an introduction to her new book. We will try and help clarify the confusion surrounding the identification of this species, describe what to look for if you intend to buy one and discuss culture to help you grow and bloom it well. We love angraecoids, and the feature that most share and what sets them apart is their spurs or nectaries. In some orchid species, attracting the pollinator is all about fooling someone (quite often an insect). Some will mimic a female insect while others will mimic another type of flower to attract that flower’s pollinator. Oftentimes the u n s u s p e c t i n g insect gets nothing in return; not the promised mate or the nectar of the Brenda Oviatt and mimicked flower. Bill Nerison With angraecoids, the pollinator is often rewarded with a sweet treat: nectar that sits in the bottom of the spur. The pollinator of Aergs. articulata is a hawk moth (DuPuy, et al 1999) whose proboscis can reach that nectar. These moths are attracted by the sweet nighttime fragrance TT (scented much like a gardenia) and by the A VI O white flower (more visible than a colored A D flower in the dark). -

Orchids: 2017 Global Ex Situ Collections Assessment

Orchids: 2017 Global Ex situ Collections Assessment Botanic gardens collectively maintain one-third of Earth's plant diversity. Through their conservation, education, horticulture, and research activities, botanic gardens inspire millions of people each year about the importance of plants. Ophrys apifera (Bernard DuPon) Angraecum conchoglossum With one in five species facing extinction due to threats such (Scott Zona) as habitat loss, climate change, and invasive species, botanic garden ex situ collections serve a central purpose in preventing the loss of species and essential genetic diversity. To support the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation, botanic gardens create integrated conservation programs that utilize diverse partners and innovative techniques. As genetically diverse collections are developed, our collective global safety net against plant extinction is strengthened. Country-level distribution of orchids around the world (map data courtesy of Michael Harrington via ArcGIS) Left to right: Renanthera monachica (Dalton Holland Baptista ), Platanthera ciliaris (Wikimedia Commons Jhapeman) , Anacamptis boryi (Hans Stieglitz) and Paphiopedilum exul (Wikimedia Commons Orchi ). Orchids The diversity, stunning flowers, seductiveness, size, and ability to hybridize are all traits which make orchids extremely valuable Orchids (Orchidaceae) make up one of the largest plant families to collectors, florists, and horticulturists around the world. on Earth, comprising over 25,000 species and around 8% of all Over-collection of wild plants is a major cause of species flowering plants (Koopowitz, 2001). Orchids naturally occur on decline in the wild. Orchids are also very sensitive to nearly all continents and ecosystems on Earth, with high environmental changes, and increasing habitat loss and diversity found in tropical and subtropical regions. -

Review of Selected Literature and Epiphyte Classification

--------- -- ---------· 4 CHAPTER 1 REVIEW OF SELECTED LITERATURE AND EPIPHYTE CLASSIFICATION 1.1 Review of Selected, Relevant Literature (p. 5) Several important aspects of epiphyte biology and ecology that are not investigated as part of this work, are reviewed, particularly those published on more. recently. 1.2 Epiphyte Classification and Terminology (p.11) is reviewed and the system used here is outlined and defined. A glossary of terms, as used here, is given. 5 1.1 Review of Selected, Relevant Li.terature Since the main works of Schimper were published (1884, 1888, 1898), particularly Die Epiphytische Vegetation Amerikas (1888), many workers have written on many aspects of epiphyte biology and ecology. Most of these will not be reviewed here because they are not directly relevant to the present study or have been effectively reviewed by others. A few papers that are keys to the earlier literature will be mentioned but most of the review will deal with topics that have not been reviewed separately within the chapters of this project where relevant (i.e. epiphyte classification and terminology, aspects of epiphyte synecology and CAM in the epiphyt~s). Reviewed here are some special problems of epiphytes, particularly water and mineral availability, uptake and cycling, general nutritional strategies and matters related to these. Also, all Australian works of any substance on vascular epiphytes are briefly discussed. some key earlier papers include that of Pessin (1925), an autecology of an epiphytic fern, which investigated a number of factors specifically related to epiphytism; he also reviewed more than 20 papers written from the early 1880 1 s onwards. -

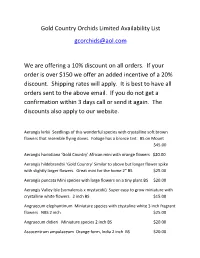

Gold Country Orchids Limited Availability List [email protected]

Gold Country Orchids Limited Availability List [email protected] We are offering a 10% discount on all orders. If your order is over $150 we offer an added incentive of a 20% discount. Shipping rates will apply. It is best to have all orders sent to the above email. If you do not get a confirmation within 3 days call or send it again. The discounts also apply to our website. Aerangis kirkii Seedlings of this wonderful species with crystalline soft brown flowers that resemble flying doves. Foliage has a bronze tint. BS on Mount $45.00 Aerangis hariotiana ‘Gold Country’ African mini with orange flowers $20.00 Aerangis hildebrandtii ‘Gold Country’ Similar to above but longer flower spike with slightly larger flowers. Great mini for the home 2” BS $25.00 Aerangis puncata Mini species with large flowers on a tiny plant BS $20.00 Aerangis Valley Isle (somalensis x mystacidii) Super easy to grow miniature with crystalline white flowers. 2 inch BS $15.00 Angraecum elephantinum Miniature species with ctystaline white 3 inch fragrant flowers NBS 2 inch $25.00 Angraecum didieri Miniature species 2 inch BS $20.00 Ascocentrum ampulaceum Orange form, India 2 inch BS $20.00 Ascocentrum aurantiacum Mini plant with bright orange flowers BS $15.00 Bulb. carunculatum ‘Big Ben’ Divisions of a very easy to flower species with bright green flowers and a plum lip. Large BS $35.00 Bulb companulatum ‘Rob’ Miniature daisy type with yellow & plum flowers Blooming size divisions $20.00 Bulb Elizabeth Ann ‘Buckelberry’ FCC/AOS Mother divisions $25.00 Bulb falcatum v. -

Traditional Therapeutic Uses of Some Indigenous Orchids of Bangladesh

® Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Science and Biotechnology ©2009 Global Science Books Traditional Therapeutic Uses of Some Indigenous Orchids of Bangladesh Mohammad Musharof Hossain* Department of Botany, University of Chittagong, Chittagong-4331, Bangladesh Correspondence : * [email protected] ABSTRACT The traditional therapeutic uses of some indigenous orchids of Bangladesh are described in this paper. Terrestrial (11) and epiphytic (18) orchids, 29 in total, are used by Bangladeshi rural and tribal people for the treatment of nearly 45 different diseases and ailments. Roots, tubers, pseudobulbs, stems, leaves and even whole plants are used. Some herbal preparations have miraculous curative properties. Unfortunately, these preparations have not typically been subjected to the precise scientific clarification and standardization which are consequently required for clinical implementations. Some of the orchids are endangered due to over-exploitation and habitat destruction. Conservation strategies for orchids and further pharmacological studies on traditional medicines are suggested. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Keywords: astavarga, conservation, ethnomedicine, herbal remedies, rasna INTRODUCTION the underground tuber of Orchis latifolia is used in the drug ‘munjatak’ pacifying cough (Khasim and Rao 1999). The Orchidaceae is the largest and most evolved family of the leaves of Vanda roxburghii have been prescribed in the flowering plants, consisting of 2500 to 35,000 species bel- ancient ‘Sanskrit’ literature for external application in rheu- onging to 750-800 genera (Dressler 1993). They are found matism, ear infections, fractures and diseases of nervous in virtually all regions around the world except the icy system. Besides these, other orchids used in local systems Antarctica, but their greatest diversity occurs in tropical and of medicine are Cleisostoma williamsonii (for bone frac- sub-tropical regions. -

D'haijère & Al. • Phylogeny and Taxonomy of Ypsilopus

[Article Category: SYSTEMATICS AND PHYLOGENY] [Running Header:] D’haijère & al. • Phylogeny and taxonomy of Ypsilopus (Orchidaceae) Article history: Received: 16 May 2018 | returned for (first) revision: 17 Dec 2018 | (last) revision received: 2 Apr 2019 | accepted: 4 Apr 2019 Associate Editor: Cassio van den Berg | © 2019 International Association for Plant Taxonomy Molecular phylogeny and taxonomic synopsis of the angraecoid genus Ypsilopus (Orchidaceae, Vandeae) Tania D’haijère,1,2 Patrick Mardulyn,1 Ling Dong,3 Gregory M. Plunkett,3 Murielle Simo-Droissart,4 Vincent Droissart2,5,6 & TariQ Stévart2,6,7 1 Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, Faculté des Sciences, C.P. 160/12, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 50 Avenue F. Roosevelt, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 2 Herbarium et BibliotHèque de Botanique africaine, C.P. 265, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Campus de la Plaine, Boulevard du TriompHe, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 3 Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York 10458-5126, U.S.A. 4 Plant Systematics and Ecology Laboratory, HigHer TeacHers’ Training College, University of Yaoundé I, P.O. Box 047, Yaoundé, Cameroon 5 AMAP, IRD, CIRAD, CNRS, INRA, Université Montpellier, Boulevard de la Lironde TA A-51/PS2, 34398 Montpellier, France 6 Missouri Botanical Garden, Africa and Madagascar Department, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, Missouri 63166-0299, U. S. A. 7 Botanic Garden Meise, Domein van BoucHout, Nieuwelaan 38, 1860 Meise, Belgium Address for correspondence: Tania D’haijère, [email protected] ORCID PM, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2154-5256; GMP, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0751-4309; MSD, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6707-8791; VD, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9798-5616 DOI Abstract Previous phylogenetic analyses focused on angraecoid orchids suggested that the genus Ypsilopus was paraphyletic and that some species of Tridactyle and Rangaeris belong to a clade that included Ypsilopus.