GIPE-033846.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Reoord- House

.950 CONGRESSIONAL _REOORD- _HOUSE. JANUAR~ 11, Asst:- Surg. l\forton W. Bak~r to be a passed assistant sur PHILIPPINE TARIFF. geon in the Navy from the 10th·day of July, -1905, upon the com Mr. PAYNE. -Mr, Speaker, I move that the House resotve pletion of three years' service in his present grade. itself into the Committee of the Whole House on the state of Asst. Surg. James H. Holloway to be a passed assistant sur the Union for the further consideration of the bill H. R. 3, and geon in the Navy from the 26th day of September, 1905, upon the pending that I ask unanimous consent that general debate on completion of three years' service in his present grade. this bill be closed at the final rising of the committee on SatUr- Gunner Charles B. Babson t-o be a chief gunner in the Navy, day ·of this week. · · from the 27th day of April, 1904, baving completed six years' The SPEAKER. The gentleman from New York asks unani service, in accordance with the provisions of section 12 of the mous consent that general debate on House bill No. 3 be closed "Navy personnel act," approved March 3, 1899, as amended by ·SatUrday next at the adjournment of the House. · the act of April 27, 1904. Mr. UNDERWOOD. Mr. Speaker, I would like to ask the Carpenter Joseph M. Simms to be a chief carpenter in the gentleman from New York as to whether he has consulted with Navy :from the 6th day of June, 1905, upon the completion of Mr. -

Missouri Compromise (1820) • Compromise Sponsored by Henry Clay

Congressional Compromises and the Road to War The Great Triumvirate Henry Clay Daniel Webster John C. Calhoun representing the representing representing West the North the South John C. Calhoun •From South Carolina •Called “Cast-Iron Man” for his stubbornness and determination. •Owned slaves •Believed states were sovereign and could nullify or reject federal laws they believed were unconstitutional. Daniel Webster •From Massachusetts •Called “The Great Orator” •Did not own slaves Henry Clay •From Kentucky •Called “The Great Compromiser” •Owned slaves •Calmed sectional conflict through balanced legislation and compromises. Missouri Compromise (1820) • Compromise sponsored by Henry Clay. It allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a Slave State and Maine to enter as a Free State. The southern border of Missouri would determine if a territory could allow slavery or not. • Slavery was allowed in some new states while other states allowed freedom for African Americans. • Balanced political power between slave states and free states. Nullification Crisis (1832-1833) • South Carolina, led by Senator John C. Calhoun declared a high federal tariff to be null and avoid within its borders. • John C. Calhoun and others believed in Nullification, the idea that state governments have the right to reject federal laws they see as Unconstitutional. • The state of South Carolina threatened to secede or break off from the United States if the federal government, under President Andrew Jackson, tried to enforce the tariff in South Carolina. Andrew Jackson on Nullification “The laws of the United States, its Constitution…are the supreme law of the land.” “Look, for a moment, to the consequence. -

Congressional Record-House

1884. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 3871 ruay, in case of necessity, depute such clerks to act for him in his official capac should cease on the bill, and that the pending amendment and others ity ; but the shipping commissioner shall be held responsible for the a{lts of every such clerk or deputy, and will be personally liable for any penalties such clerk or to be offered shall then be voted on. deputy may incur by the violation of uny of the provisions of this title; and all :h1r. FRYE. I supposed that general debate had now ceased. I will acts done by a clerk as such deputy shall be as valid and binding as if done by ask that this bill be taken up for consideration to-morrow morning after the shipping commissioner. the morning business and that debate be limited to five minutes. Again: Mr. MORGAN. Ishallhavetoobjectto that. Ihaven4>texpressed EC. 4507. Every shipping commissioner shall lease, rent, or procure, at his any opinions on the bill, because the bill has not been in a shape that I own cost, suitable premises for the transaction of business, and for the preser vation of the books and other documents connected therewith; and these prem could gi•e my views of it properly. I shall be very brief in what I have ises shall be styled the shipping commissioner's office. to say, but I can not say it in five minutes. :h1r. CONGER. Now will the Senator read the last section but one ltlr. FRYE. I then ask unanimous consent that the bill be taken up in the act. -

Congressional Record- Senate. July 28, \' -Senate

\ \ 2806 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- SENATE. JULY 28, \' -SENATE. A bill (S. 2837) granting a pension to Matilda Robertson (with accompanying paper); to the Committee on Pensions. MoNDAY, July ~8, 1913. By .Mr. McLEAN : Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. Forrest J. Prettyman, D. D. A bill (S. 2838) granting an increase of pension to Ruth El. The VICE PRESIDENT resumed the chair. Putnam (with accompanying paper) ; and The Journal of the proceedings of Saturday last was read and A bill ( S. 2 39) granting an increase of pension to Theodore C. approved. Bates (with accompanying paper); to the Committee on Pensions. By Mr. PO~lERENE: SENATOR FROM GEORGI.A.. A bill ( S. 2840) for the relief of Edgar R. Kellogg; and The VICE PRESIDENT laid before the Senate a certificate A bill (S. 2841) for the relief of the estate of Francis El, from the governor of Georgia certifying the election of Hon. Lacey ; to the Committee on Claims. AUGUSTUS 0. BACON as a Senator from the State of Georgia, By Mr. SHIELDS: _ which was read and ordered to be filed, as follows: A bill ( S. 2842) to reimburse Jetta Lee, late postmaster STATE OF GEORGIA, at Newport, Tenn., for key funds stolen from post office (with EXECUTIVE DEPAJlTMENT, accompanying paper) ; to the Committee on Claims. Atlanta, July 25, 191S. To the President of the Senate of the UnUea States: THE .MODERN BY-PRODUOT COKE OVEN (S. DOC. NO. 145). This is to certify that at an election held pursuant to law in the l\I~·· BANKHEAD. I ask unanimous consent to have printed State of Georgia on the 15th day of July, 1913, by the electors in said State. -

Open Mangiaracina James Crisisinfluence.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE INFLUENCE OF THE 1830s NULLIFICATION CRISIS ON THE 1860s SECESSION CRISIS JAMES MANGIARACINA SPRING 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in History with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Amy Greenberg Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of History and Women’s Studies Thesis Supervisor Mike Milligan Senior Lecturer in History Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This thesis aims to connect the constitutional arguments for and against secession during the Nullification Crisis of 1832 with the constitutional arguments for and against secession during the Secession Crisis of 1860-1861. Prior to the Nullification Crisis, Vice President John C. Calhoun, who has historically been considered to be a leading proponent of secession, outlined his doctrine of nullification in 1828. This thesis argues that Calhoun’s doctrine was initially intended to preserve the Union. However, after increasingly high protective tariffs, the state delegates of the South Carolina Nullification Convention radicalized his version of nullification as expressed in the Ordinance of Nullification of 1832. In response to the Ordinance, President Andrew Jackson issued his Proclamation Regarding Nullification. In this document, Jackson vehemently opposed the notion of nullification and secession through various constitutional arguments. Next, this thesis will look at the Bluffton Movement of 1844 and the Nashville Convention of 1850. In the former, Robert Barnwell Rhett pushed for immediate nullification of the new protective Tariff of 1842 or secession. In this way, Rhett further removed Calhoun’s original intention of nullification and radicalized it. -

The Free-Trade Doctrine and Commercial Diplomacy of Condy Raguet

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Economics Department Working Paper Series Faculty Scholarship and Creative Work 5-11-2011 The Free-Trade Doctrine and Commercial Diplomacy of Condy Raguet Stephen Meardon Bowdoin College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/econpapers Part of the Economic History Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Meardon, Stephen, "The Free-Trade Doctrine and Commercial Diplomacy of Condy Raguet" (2011). Economics Department Working Paper Series. 1. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/econpapers/1 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship and Creative Work at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Department Working Paper Series by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FREE-TRADE DOCTRINE AND COMMERCIAL DIPLOMACY OF CONDY RAGUET Stephen Meardon Department of Economics, Bowdoin College May 11, 2011 ABSTRACT Condy Raguet (1784-1842) was the first Chargé d’Affaires from the United States to Brazil and a conspicuous author of political economy from the 1820s to the early 1840s. He contributed to the era’s free-trade doctrine as editor of influential periodicals, most notably The Banner of the Constitution. Before leading the free-trade cause, however, he was poised to negotiate a reciprocity treaty between the United States and Brazil, acting under the authority of Secretary of State and protectionist apostle Henry Clay. Raguet’s career and ideas provide a window into the uncertain relationship of reciprocity to the cause of free trade. -

Congressional Record-House. May 25

3312 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. MAY 25, Louis and elsewhere, have been stopped and are now stopped from Mr. ED~fUNDS. We will look at. t,hat, and t.ake it up by and by, doing their \York, which is very important, not onlJ:" to th_em.but to if necessary. the community. The case hasl.Jeen very thoroughly mvest1gared and The PRESIDENT pro ·tempore. Pursuant to order, legislative and it is thought by the Commissioner that these men did not viol:1te the executive business will be suspended and the Senate will proceed- law, but there is some little obscurity about it. Mr. D.A.VIS. I think the bill had better be sent back to me, and I M1·. ED~1UNDS. If the State of Missouri is deprived of tha.t most will1·eport it to-morrow morning. · useful beverage, vinegar, I certainly cannot stand in the way of the Mr. EDMUNDS. It can be passed by and by. There is no need to bill being taken up; and I withdraw my call for the regular order sencl it ba{}k, for the time being. Mr. DAVIS. I withdraw the report. Mr. BOGY. I move to take up House bill No. 1800. Mr. EDMUNDS. I call for the regula~ order. The motion was agreed to; and the bill (H. R. No.1800) for there The PRESIDENT JYI'O ternpo1'e. Pursuant to order, legislative and lief of Kendrick & Avis; Kuner, Zisemann & Zott; Kuner & Zott, all executive business will be suspended and the Senate will proceed to of Saint Louis, :Missouri; and Nachtrieb & Co., of Galion, Ohio, was the consideration of the articles of impea{)hment exhibited by the considered as in Committee of the Whole. -

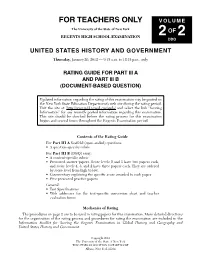

Document-Based Question)

FOR TEACHERS ONLY VOLUME The University of the State of New York 2 OF 2 REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION DBQ UNITED STATES HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT Thursday, January 26, 2012 — 9:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m., only RATING GUIDE FOR PART III A AND PART III B (DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTION) Updated information regarding the rating of this examination may be posted on the New York State Education Department’s web site during the rating period. Visit the site at: http://www.p12.nysed.gov/apda/ and select the link “Scoring Information” for any recently posted information regarding this examination. This site should be checked before the rating process for this examination begins and several times throughout the Regents Examination period. Contents of the Rating Guide For Part III A Scaffold (open-ended) questions: • A question-specific rubric For Part III B (DBQ) essay: • A content-specific rubric • Prescored answer papers. Score levels 5 and 1 have two papers each, and score levels 4, 3, and 2 have three papers each. They are ordered by score level from high to low. • Commentary explaining the specific score awarded to each paper • Five prescored practice papers General: • Test Specifications • Web addresses for the test-specific conversion chart and teacher evaluation forms Mechanics of Rating The procedures on page 2 are to be used in rating papers for this examination. More detailed directions for the organization of the rating process and procedures for rating the examination are included in the Information Booklet for Scoring the Regents Examination in Global History and Geography and United States History and Government. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Global Visions. Teaching Suggestions and Activity

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 838 SO 029 699 TITLE Global Visions. Teaching Suggestions and Activity Masters for Unit 1: The Global Marketplace. INSTITUTION Procter and Gamble Educational Services, Cincinnati, OH. PUB DATE 1995-00-00 NOTE 14p.; Full-sized wall poster is not available from EDRS. Color photographs may not reproduce clearly. For related units, see SO 029 700-701. AVAILABLE FROM Learning Enrichment, Inc., P.O. Box 3024, Williamsburg, VA 08534-0415. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Context; Economic Change; *Economic Development; *Economics; *Economics Education; Foreign Countries; *Global Approach; High Schools; Maps; Social Studies; Youth IDENTIFIERS *Economic Growth; *Global Issues ABSTRACT This is a classroom-ready program about the U.S. economy's number one challenge: globalization. Few historical forces have more power to shape students' lives than globalization, the gradual economic integration of all the world's nations. This program is designed to supplement social studies courses in economics, government, U.S. and world history, world cultures, and geography. The unit contains a newsletter, for students in grades 9-12, four reproducible activity masters included in a four-page teacher's guide, and a full-color map, "The Global Marketplace," presented as a full-sized wall poster. The learning objectives are:(1) to define the word 'globalization' as it relates both to the merging of the world's economies and to shifts in the way U.S. corporations operate;(2) to explain why globalization requires workers at all levels to have more flexibility, more skills, and more knowledge;(3) to list two advantages of globalization for consumers;(4) to describe at least two challenges of globalization for businesses; (5) to list three main categories of goods that are exported and imported by the United States; and (6) to explain how the history of U.S. -

A History of US Trade Policy

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Clashing over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy Volume Author/Editor: Douglas A. Irwin Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBNs: 978-0-226-39896-9 (cloth); 0-226-39896-X (cloth); 978-0-226-67844-3 (paper); 978-0-226-39901-0 (e-ISBN) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/irwi-2 Conference Date: n/a Publication Date: November 2017 Chapter Title: Index Chapter Author(s): Douglas A. Irwin Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c14306 Chapter pages in book: (p. 823 – 860) Index Acheson, Dean: on Hull’s reciprocal trade policy stance of, 541, 549– 50, 553; Trade agreement commitment, 422– 23; multi- Act (1974) opposition of, 549– 50, 553; lateral trade agreement role of, 458–59, trade adjustment assistance stance of, 462– 63, 476, 478, 505; reciprocal trade 523, 553. See also American Federation agreement role of, 466, 468, 469, 470 of Labor (AFL); Congress of Industrial Adams, John: on cessation of trade, 46; Organizations commercial negotiations of 1784–86 African Growth and Opportunity Act (2000), by, 51– 54; reciprocal trade agreements 662 stance of, 97, 98; on tariffs, 46; trade Agricultural Adjustment Act, 418, 419– 20, policy philosophy of, 68; treaty plan of 511 1776 by, 46 agricultural products: American System Adams, John Quincy: American System sup- impacts on, 143; antebellum period port from, 148, 153; in election of 1824, importance of, 193; “chicken war” over, 148; in election of 1828, 148–49, -

1829 *I861 Appropriations, Banking, and the Tariff

1829 *I861 Appropriations, Banking, and the Tariff The Committee of Ways and Means nence in the decades immediately preceding e period 1829-1861, the committee’s chairman came to be regarded as the d the tariff. The c ver the nation’s the creation of policy, probably to a larger extent than any other ee during the antebellum era. “The great body of ndrew Jackson’s election to the Presidency marked the culmination legislatzon was referred A of a period of social, economic, and political change that began to the committee of ways with the American Revolution and intensified after the War of 1812. One of the most significant of these changes was the introduction of and means, whzch then democratic reforms in order to broaden the political base, such as the had charge of all extension of the vote to all adult white males. The Virginia dynasty appropnatzons and of all ended with the presidential election of 1824. From the disaffection fax laws, and whose surrounding the election and Presidency of John Quincy Adams, a chazrman was recognzzed new and vigorous party system began to coalesce at the state level. as leader of the House, The second American party system developed incrementally be- practzcally controllang the tween 1824 and 1840. The principal stimulants to the development of the new parties were the presidential elections. By 1840, two parties order of zts buszness. ” of truly national scope competed for control of ofices on the munici- (John Sherman, 1895) pal, state, and federal level. The founders of these new parties were not all aristocratic gentlemen. -

U.S. Trade Policy in Historical Perspective

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES U.S. TRADE POLICY IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Douglas A. Irwin Working Paper 26256 http://www.nber.org/papers/w26256 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2019 I am grateful to Gene Grossman for helpful comments. This paper is forthcoming in the Annual Review of Economics. 10.1146/annurev-economics-070119-024409. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2019 by Douglas A. Irwin. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. U.S. Trade Policy in Historical Perspective Douglas A. Irwin NBER Working Paper No. 26256 September 2019 JEL No. F13,N71,N72 ABSTRACT This survey reviews the broad changes in U.S. trade policy over the course of the nation’s history. Import tariffs have been the main instrument of trade policy and have had three main purposes: to raise revenue for the government, to restrict imports and protect domestic producers from foreign competition, and to reach reciprocity agreements that reduce trade barriers. These three objectives – revenue, restriction, and reciprocity – accord with three consecutive periods in history when one of them was predominant. The political economy of these tariffs has been driven by the interaction between political and economic geography, namely, the location of trade-related economic interests in different regions and the political power of those regions in Congress.