1 Canada Case Study Introduction the Stockholm Convention On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threats to Sources of Drinking Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Health in Canada Threats to Sources of Drinking Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Health in Canada

THREATS TO SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER AND AQUATIC ECOSYSTEM HEALTH IN CANADA THREATS TO SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER AND AQUATIC ECOSYSTEM HEALTH IN CANADA NWRI Scientific Assessment Report Series No. 1 NATIONAL WATER RESEARCH INSTITUTE ENVIRONMENT CANADA © Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2001 To obtain additional copies: Science Liaison Branch National Water Research Institute Environment Canada 867 Lakeshore Road, P.O. Box 5050 Burlington, ON L7R 4A6 Or download a copy in pdf format from the NWRI web site: http://www.cciw.ca/nwri/ National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication data Main entry under title: Threats to sources of drinking water and aquatic ecosystem health in Canada (NWRI Scientific Assessment Report Series, ISSN 1499-5905; no. 1) Issued also in French under title: Menaces pour les sources d’eau potable et les écosystèmes aquatiques au Canada. ISBN 0-662-31315-1 Cat. No. En40-237/1-2001E 1. Drinking water – – Contamination – – Canada – – Congresses. 2. Water – – Pollution – – Canada – – Congresses. 3. Water quality – – Canada – – Congresses. I. National Water Research Institute (Canada) II. Series. TD226.T47 2001 363.6’1’0971 C2001-980362-1 This report may be cited as follows: Environment Canada. 2001. Threats to Sources of Drinking Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Health in Canada. National Water Research Institute, Burlington, Ontario. NWRI Scientific Assessment Report Series No. 1. 72 p. ii Table of Contents Foreword . v Executive Summary . .. vii 1. Waterborne Pathogens . 1 2. Algal Toxins and Taste and Odour . 5 3. Pesticides . 9 4. Persistent Organic Pollutants and Mercury . 13 5. Endocrine Disrupting Substances . 17 6. Nutrients—Nitrogen and Phosphorus . -

Biopesticides – Expectations for Control

Biopesticides – Expectations for Control Jeanette Gaultier, Crops Knowledge Centre, Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives, Carman, MB R0G 0J0 Email: [email protected] A biopesticide is a naturally occurring organism or substance that can be used to control pests. The term ‘biopesticide’ can be applied to microorganisms, biochemicals and plant extracts that are used as pest control products. Although not the case in Canada, some countries also consider plants with ‘incorporated protectants’ (i.e. transgenic crops) as biopesticides. Interest in biopesticides is increasing because such products are often recognized as ‘reduced’ or ‘low’ risk alternatives to conventional pesticides. In Canada, a pesticide is considered to be of reduced risk if human health and/or environmental risks are decreased relative to other pesticides registered for the same use. General characteristics of reduced risk pesticides include (PMRA, 2002): • Low toxicity; • Limited effects on non-target organisms; • Good environmental profile; • Low pest resistance potential; • Decreased application rates or applications; and • Compatible with integrated pest management principles. A product doesn’t have to be a biopesticide to be considered reduced risk. Conversely, biopesticides are often, but not always, classified as reduced risk. Biopesticides currently account for only a small percentage (~1%) of the global pesticide market (Copping and Menn, 2000; Warrior, 2000; Rodgers, 1993). These products have generally found commercial success in niche markets such as horticulture, greenhouse, nursery and ornamental, and organic production. Uptake and use of biopesticides in conventional field crop agriculture remains low. Why is this the case? What should agricultural producers expect from biopesticides? Regulatory Expectations All pesticides, including biopesticides, available for use in Canada are regulated by Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA). -

Master List of Actions on the Reduction And/Or Elimination of Releases of Pops

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME Chemicals MMAASSTTEERR LLIISSTT OOFF AACCTTIIOONNSS On the Reduction and/or Elimination of the Releases of Persistent Organic Pollutants Fourth Edition Prepared by UNEP Chemicals June 2002 INTER-ORGANIZATION PROGRAMME FOR THE SOUND MANAGEMENT OF CHEMICALS IOMC A cooperative agreement among UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO, UNITAR and OECD This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC) The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating Organizations), following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the field of chemical safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a Participating Organization. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment. The photograph on the cover page was taken by Steve C. Delaney. Copies of this report are available from: UNEP Chemicals 11-13, chemin des Anémones CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE Switzerland Phone: +41 22 917 1234 Fax: +41 22 797 3460 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.chem.unep.ch/pops UNEP CHEMICALS UNEP Chemicals is part of UNEP’s Technology, Industry and Economics Division UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME Chemicals MMAASSTTEERR LLIISSTT OOFF AACCTTIIOONNSS On the Reduction and/or Elimination of the Releases of Persistent Organic Pollutants Fourth Edition Issued by UNEP Chemicals Geneva, Switzerland June 2002 Table of contents Page Executive summary i Introduction xvii Organization and xviii structure of the tables Chapter 1 Information on global activities aiming at the reduction 1 and/or elimination of releases of POPs received from Inter-Governmental Organizations. -

Defending Nature Against Rodenticides

Defending Nature Against Rodenticides LAW 391D Topics in Environmental Law Green Rights & Warrior Lawyers Marie Turcott December 18, 2019 Page 12 I. INTRODUCTION: RATS, RODENTICIDES, AND RIGHTS OF NATURE .................... 2 II. THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR PESTICIDE REGULATION IN CANADA ............ 5 A. Federal Regulations ............................................................................................................................ 6 1. Developments in Federal Regulation of Rodenticides ...................................................................... 8 B. Provincial Regulation ....................................................................................................................... 10 C. Municipal Role .................................................................................................................................. 13 III. THE USE OF SECOND-GENERATION ANTICOAGULANT RODENTICIDES IS INCONSISTENT WITH THE CURRENT REGULATORY FRAMEWORK .................... 14 A. There is Reasonable Certainty that Harm Results from SGAR Use ........................................... 16 1. Risks to Nature: Wildlife and the Environment .............................................................................. 16 i. Direct poisoning of non-target primary consumers .................................................................................... 16 ii. Indirect poisoning of secondary consumer predator and scavenger species .............................................. 18 iii. Poisoning of the environment -

Pesticides: Making the Right Choice For

House of Commons Committees - ENVI (36-2) - Pesticides: Making the Right Choice for... Page 1 of 1 Secilon hforne Francais:^ JaSte off Contend > hM Publications Options Gorrtrerttee Report Back_tp_raports and responses * PESTICIDES MAKING THE RIGHT CHOICE FOR THE PROTECTION OF HEALTH AND THE ENVIRONMENT Report of the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development May 2000 Jk, > No<: http://www2.paFl. gc.ca/'HouscPiiblrcationa/Publication.aspx?DocId=1033697&Laiiguage=E.„ 7/6/2009 House of Commons Committees - ENVI (36-2) - Pesticides: Making the Right Choice for... Page 1 of 4 Section Home I'fvWfi i >tlert Publications Options Committee Report Back to reports and responses Table of Contents List of Members Mandate CHAIR'S PREFACE TO THE REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: KEY DIRECTIONS FOR CHANGE Introduction PART A: BACKGROUND Chapter 1 - THE FEDERAL REGULATORY SYSTEM AND THE ROLE OF THE PEST MANAGEMENT REGULATORY AGENCY Chapter 3 - THE NEED FOR NEW LEGISLATION An Outdated Statute Guiding Principles for the New Legislation PART B: PESTICIDES AND THEIR HARMFUL EFFECTS Chapter 3 - HISTORY OF PESTICIDE USE The Main Classes of Chemical Pesticides Sectors of Pesticide Use General Characteristics of Pesticides Appendix 3,1: Pesticides and Golf Courses Appendix 3.2: Description of Major Groups of Chemical Pesticides Chapter 4 - PESTICIDES IN THE ENVIRONMENT Transportation and Dispersion of Pesticides in Soil, Air and Water Long-Range Transportation of Pesticides: Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) Increasing Levels of Pesticides in the -

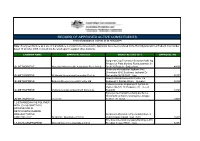

Current List. RECORD of APPROVED ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS for CHEMICAL PRODUCTS

CHEMICAL COMPANY MANUFACTURER SITE APPROVAL NO Current List RECORD OF APPROVED ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS FOR CHEMICAL PRODUCTS The Current Approval List is also accessible via the NRA web page on: http://www.nra.gov.au/tgac/tgac.pdf as at 10 December 2001 Page 1 of 152 CHEMICAL COMPANY MANUFACTURER SITE APPROVAL NO 1,3-dichloropropene Dow AgroSciences Australia Limited The Dow Chemical Company 52481 Building A-915 Freeport Texas 77541 USA 1,3-dichloropropene Dow AgroSciences Australia Limited Dow Chemical G.m.b.H. 52747 Werk Stade D-2160 Stade GERMANY 2-(Thiocyanomethylthio)benzothiazole Buckman Laboratories Ltd Buckman Laboratories Inc 44403 (TCMTB) 1256 North McLean Boulevard Memphis Tennessee 38108-0305 USA 2,4-D A H Marks Australia Limited A H Marks & Company Limited 51006 Wyke Lane Wyke Bradford West Yorkshire BD12 9EJ United Kingdom 2,4-D Artfern Pty Ltd Dalian Songliao Chemical Industrial Company Ltd 44245 22 Gongxing Road Ganjingzi Dalian Liaoning 116031 CHINA 2,4-D Ancom Australia Pty Ltd Ancom Crop Care SDN BHD 47430 Persiaran Selangor 40000 Shah Alam Selangor D.E. MALAYSIA Page 2 of 152 CHEMICAL COMPANY MANUFACTURER SITE APPROVAL NO 2,4-D Dow AgroSciences Australia Limited Sanachem (Pty) Ltd 47158 Hytor Road Chloorkop Kempton Park 1620 SOUTH AFRICA 2,4-D Dow AgroSciences Australia Limited Dow Agro Sciences (NZ) Ltd 47548 DowElanco (NZ) Limited Plant 1 89 Paritutu Road New Plymouth 4620 NEW ZEALAND 2,4-D Dow AgroSciences Australia Limited Dow Agro Sciences LLC 47550 The Dow Chemical Company Plant 1 Midland Michigan 48640 USA 2,4-D Farmoz Pty Ltd Choseright Limited 48691 Jin Jiang Agricultural Chemical Factory No 14 Hong Qiao North Road Jingjiang City Jiangsu Province CHINA 2,4-D Farmoz Pty Ltd Atanor S.A. -

Pest Management Policy-Cofc-External Review14jan2019

CPS2019-1518 Attachment 6 CPS2019-1518 Pest Management Policy - Att6 Page 1 of 16 ISC: Unrestricted CPS2019-1518 Pest Management Policy - Att6 Page 2 of 16 ISC: Unrestricted Dow AgroSciences Canada Inc. dowagro.ca Suite 2400, 215 - 2 Street SW, Calgary, AB T2P 1M4 January 11, 2019 Steven Snell Conservation Policy Team Lead The City of Calgary Floor 7, Calgary Public Building: 205 - 8th Ave SE P.O. Box 2100, Station M #54 Calgary, AB Canada T2P 2M5 T: 403.268.3527; M: 403.850.2091 Dear Mr. Snell: SUBJECT: CITY OF CALGARY PEST MANAGEMENT POLICY - EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDER REVIEW Comments Provided by Dow AgroSciences Canada Inc. Dow AgroSciences Canada Inc. (DAS) appreciates the opportunity to provide the City of Calgary with comments for the stakeholder consultation related to the principles that will become the policy statements in the pest management policy within the City. As requested we have made comments and proposed changes to the strategies, and we have proposed a priority level to each one of them. Please also refer to our letter dated February 6th 2017, which includes further details about our position on pest management within the City. Dow AgroSciences would welcome an opportunity to meet with you or other City staff to discuss our knowledge of pest control products and pest management approaches. For any further information, do not hesitate to contact me directly, Sincerely, Regulatory & Environmental Affairs Manager CPS2019-1518 Pest Management Policy - Att6 Page 3 of 16 ISC: Unrestricted How wonderful is it when something doesn't happen ... when "something" is cancer? Check out our Cancer Prevention Tips Sign up for occasional news, and science-based advice and actions. -

2010 Pesticide Sales in British Columbia Integrated Pest Management Program Ministry of Environment

2010 Pesticide Sales in British Columbia Integrated Pest Management Program Ministry of Environment Executive Summary In order for any regulatory agency to operate in an effective, risk-based fashion, it is important to have current data on key aspects of the industries it regulates. The Ministry of Environment’s Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Program regulates the sale and use of pesticides in British Columbia, and strives to reduce risk to human health and the environment from pesticides by carrying out targeted actions and strategies. To help achieve this goal, we undertook an analysis of current data on the sale of pesticides in the province, which can be used as a tool in the guidance of policy development and program management. To carry out this analysis, IPM Program staff designed and built a database and information management system to process the large volume of pesticide sales and use data that is collected annually from pesticide vendors and users. We then used this system to analyse the 2010 sales of all commercial pesticides, breaking down the data by pesticide type, sector of use, region of sale, and agricultural pesticide use intensity. Where possible, our data was then compared to previous data for B.C. from 2003, and the most current data from other provinces. The highlights of our results for 2010 commercial pesticide sales include: Pesticide vendors in B.C. sold a total of 2,955,302 kilograms of commercial formulated products, which represented a total of 1,289,933 kilograms of active ingredient. The top five active ingredients sold were insecticidal mineral oil, glyphosate, sulphur, chlorothalonil, and herbicidal mineral oil. -

Pesticides in the Air, Atmospheric Deposits, and Surface Waters of Canada

Pesticides in the Air, Atmospheric Deposits, and Surface Waters of Canada by Paul G. Messing A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Soil Science University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 by Paul G. Messing 2 ABSTRACT Messing, Paul G., Ph.D. The University of Manitoba, May 2014. Pesticides in the Air, Atmospheric Deposits, and Surface Waters of Canada. Major Professor; Annemieke Farenhorst. In Canada, more than 35 million kilograms of pesticide active ingredients are applied annually on agricultural land with about 84% of this mass applied in the Canadian Prairies Provinces. Pesticide residues may become airborne through post-volatilization losses from land, water or vegetative surfaces, via wind-eroded soil, and by spray drift during pesticide application. Once in the air, pesticides may be dispersed and transported as parent molecules or as degradation products. Currently used and legacy pesticide air concentrations were measured in the agricultural region of the Prairie Provinces and the northern subarctic and arctic regions of Canada in 2005 and 2007. More intensive air sampling was conducted across the province of Manitoba in 2008 and 2009. Separate wet versus dry atmospheric deposition samples and wetland water samples were also taken in these years. In general, pesticides were detected in the monitored environmental media as mixtures with the frequency and concentrations detected being largest for pesticides that were applied on-site. Although the most commonly used herbicides in western Canadian agriculture were frequently present in the air in the regions where they are applied, they appeared infrequently and at low levels in the Canadian Subarctic, Arctic, and remote sites far from agricultural pesticide applications. -

RECORD of APPROVED ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS This Information Is Current As at 19/02/2014

RECORD OF APPROVED ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS This information is current as at 19/02/2014 Note: Evergreen Nurture as a site of manufacture is known to be non-existent. Approvals have been restored to the Record pursuant to a Federal Court Order dated 13 October 2008. It should not be relied upon to support other products. COMMON NAME APPROVAL HOLDER MANUFACTURE SITE APPROVAL NO. Syngenta Crop Protection Schweizerhalle Ag Production Plant Muttenz Rothausstrasse 61 (S)-METHOPRENE Novartis Animal Health Australasia Pty. Limited Ch-4133 Pratteln Switzerland 44095 Wellmark International Jayhawk Fine Chemicals 8545 Southeast Jayhawk Dr (S)-METHOPRENE Wellmark International (australia) Pty Ltd Galena Ks 66739-0247 Usa 55179 Babolna Bioenvironmental Centre Ltd (S)-METHOPRENE Babolna Bioenvironmental Centre Ltd Budapest X Szallas Utca 6 Hungary 58495 Vyzkumny Ustav Organickych Syntez As Rybitvi 296 532 18 Pardubice 20 Czech (S)-METHOPRENE Vyzkumny Ustav Organickych Zyntez As Republic 59145 Synergetica-changzhou Gang Qu Bei Lu Weitang New District Changzhou Jiangsu (S)-METHOPRENE Zocor Inc 213033 Pr China 59428 1,2-ETHANEDIAMINE POLYMER WITH (CHLOROMETHYL) OXIRANE AND N- METHYLMETHANAMINE MANUFACTURING Buckman Laboratories Pty Ltd East Bomen CONCENTRATE Buckman Laboratories Pty Ltd Road Wagga Wagga Nsw 2650 56821 The Dow Chemical Company Building A-915 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE Dow Agrosciences Australia Limited Freeport Texas 77541 Usa 52481 COMMON NAME APPROVAL HOLDER MANUFACTURE SITE APPROVAL NO. Dow Chemical G.m.b.h. Werk Stade D-2160 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE Dow Agrosciences Australia Limited Stade Germany 52747 Agroquimicos De Levante (dalian) Company Limited 223-1 Jindong Road Jinzhou District 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE Agroquimicos De Levante, S.a. -

Pesticides Literature Review

Pesticides Literature Review Project Team Members: Margaret Sanborn,n MD, CCFP, FCFP McMaster University Donald Cole,e MD, FRCP(C) University of Toronto Kathleen Kerr,r MD, Dip. Env. Health Environmental Health Clinic, Sunnybrook & Women’s College Health Sciences Centre Cathy Vakil,l MD, CCFP Queen’s University Luz Helena Sanin,n MD, MPH, ScD University of Toronto Kate Bassil,l MA, PhD(c) University of Toronto CONTACT: The Ontario College of Family Physicians 357 Bay Street, Mezzanine Toronto, Ontario M5H 2T7 Tel: (416) 867-9646 ▪ Fax: (416) 867-9990 Email: [email protected] ▪ Website: www.ocfp.on.ca April 23, 2004 Systematic Review of Pesticide Human Health Effects Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 2 References................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 2 Methods ................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 3 Solid Tumours ....................................................................................................................... 12 References............................................................................................................................. -

The Regulation of Pesticides in Canada

Pest Management Regulatory Agency Fact Sheet on The Regulation of Pesticides in Canada Pesticides are carefully regulated in Canada through a Pesticides imported into, or sold or used in Canada are program of premarket scientific assessment, regulated nationally under the Pest Control Products enforcement, education and information Act (PCP Act) and Regulations. The PMRA is dissemination. These activities are shared among responsible for administering this legislation, registering federal, provincial/territorial and municipal governments, pest control products, re-evaluating registered products and are governed by various acts, regulations, and setting maximum residue limits under the Food and guidelines, directives and bylaws. Although it is a Drugs Act (FDA). complex process, regulators at all levels work together towards the common goal—helping protect Canadians Companies that wish to have the right to sell a pest from any risks posed by pesticides and ensuring that control product in Canada must submit detailed pest control products do what they claim to on the label. information and data to be evaluated by the PMRA. Companies must provide all the scientific studies necessary for determining that the product is acceptable The Federal Role in terms of safety, merit and value. Depending on the complexity of the submission, a complete evaluation can The Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) of take anywhere from a number of weeks to a year or Health Canada has the mandate to protect human health more. The evaluation results either in the product being and the environment by minimizing the risks associated granted registration and allowed for sale and use in with pest control products, while enabling access to pest Canada, or in the product being refused registration.