Lankesteriana IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Issue

ISSN 1409-3871 VOL. 8, No. 2 AUGUST 2008 Capsule development, in vitro germination and plantlet acclimatization in Phragmipedium humboldtii, P. longifolium and P. pearcei MELANIA MUÑOZ & VÍCTOR M. JI M ÉNEZ 23 Stanhopeinae Mesoamericanae IV: las Coryanthes de Charles W. Powell GÜNTER GERLACH & GUSTA V O A. RO M ERO -GONZÁLEZ 33 The Botanical Cabinet RUDOLF JENNY 43 New species and records of Orchidaceae from Costa Rica DIE G O BO G ARÍN , ADA M KARRE M ANS & FRANCO PU P ULIN 53 Book reviews 75 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON ORCHIDOLOGY LANKESTERIANA THE IN T ERNA ti ONAL JOURNAL ON ORCH I DOLOGY Copyright © 2008 Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica Effective publication date: August 29, 2008 Layout: Jardín Botánico Lankester. Cover: Plant of Epidendrum zunigae Hágsater, Karremans & Bogarín. Drawing by D. Bogarín. Printer: Litografía Ediciones Sanabria S.A. Printed copies: 500 Printed in Costa Rica / Impreso en Costa Rica R Lankesteriana / The International Journal on Orchidology No. 1 (2001)-- . -- San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica, 2001-- v. ISSN-1409-3871 1. Botánica - Publicaciones periódicas, 2. Publicaciones periódicas costarricenses LANKESTERIANA 8(2): 23-31. 2008. CAPSULE DEVELOPMENT, IN VITRO GERMINATION AND PLANTLET ACCLIMATIZATION IN PHRAGMIPEDIUM HUMBOLDTII, P. LONGIFOLIUM AND P. PEARCEI MELANIA MUÑOZ 1 & VÍCTOR M. JI M ÉNEZ 2 CIGRAS, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San Pedro, Costa Rica Jardín Botánico Lankester, Universidad de Costa Rica, P.O. Box 1031, 7050 Cartago, Costa Rica [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT . Capsule development from pollination to full ripeness was evaluated in Phragmipedium longifolium, P. -

Sistemática Y Evolución De Encyclia Hook

·>- POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS ~ BIOLÓGICAS CICY ) Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas SISTEMÁTICA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE ENCYCLIA HOOK. (ORCHIDACEAE: LAELIINAE), CON ÉNFASIS EN MEGAMÉXICO 111 Tesis que presenta CARLOS LUIS LEOPARDI VERDE En opción al título de DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS (Ciencias Biológicas: Opción Recursos Naturales) Mérida, Yucatán, México Abril 2014 ( 1 CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN CIENTÍFICA DE YUCATÁN, A.C. POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS OSCJRA )0 f CENCIAS RECONOCIMIENTO S( JIOI ÚGIC A'- CICY Por medio de la presente, hago constar que el trabajo de tesis titulado "Sistemática y evo lución de Encyclia Hook. (Orchidaceae, Laeliinae), con énfasis en Megaméxico 111" fue realizado en los laboratorios de la Unidad de Recursos Naturales del Centro de Investiga ción Científica de Yucatán , A.C. bajo la dirección de los Drs. Germán Carnevali y Gustavo A. Romero, dentro de la opción Recursos Naturales, perteneciente al Programa de Pos grado en Ciencias Biológicas de este Centro. Atentamente, Coordinador de Docencia Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. Mérida, Yucatán, México; a 26 de marzo de 2014 DECLARACIÓN DE PROPIEDAD Declaro que la información contenida en la sección de Materiales y Métodos Experimentales, los Resultados y Discusión de este documento, proviene de las actividades de experimen tación realizadas durante el período que se me asignó para desarrollar mi trabajo de tesis, en las Unidades y Laboratorios del Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C., y que a razón de lo anterior y en contraprestación de los servicios educativos o de apoyo que me fueron brindados, dicha información, en términos de la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor y la Ley de la Propiedad Industrial, le pertenece patrimonialmente a dicho Centro de Investigación. -

The Important Role That the Botanical Garden of The

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica TÉLLEZ VELASCO, AIDA THE IMPORTANT ROLE THAT THE BOTANICAL GARDEN OF THE NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO PLAYS IN THE CONSERVATION OF MEXICAN ORCHIDS Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 156-160 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813031 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 156-160. 2007. THE IMPORTANT ROLE THAT THE BOTANICAL GARDEN OF THE NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO PLAYS IN THE CONSERVATION OF MEXICAN ORCHIDS AIDA-TÉLLEZ VELASCO Jardín Botánico del Instituto de Biología, UNAM. 3er. Circuito Exterior. Cd. Universitaria. Apdo. Postal 70-614 México, D.F., C.P. 04510. México [email protected] RESUMEN. El Jardín Botánico del Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México ubicado en la Ciudad de México, México; asentado en terrenos de origen volcánico en un matorral xerófito; tiene el propósito de mantener colecciones de plantas vivas representativas de la diversidad vegetal de México, que sirven de apoyo a la investigación, conservación, educación y Divulgación de la diversidad botánica. El Jardín posee una colección Viva de Orquídeas, tanto epífitas como terrestres, en la que se han llevado a cabo diferentes actividades. Con este trabajo se enfatiza el papel que juega el Jardín Botánico de la UNAM, en la conservación de la familia Orchidaceae de México. -

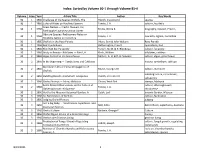

Index Sorted by Title

Index sorted by Title Volume Issue Year Article Title Author Key Words 31 5 1967 12th Western Orchid Congress Jefferies, George Western Orchid Congress 31 5 1967 12th Western Orchid Congress — Photo Flashes Philpott, R. G. Western Orchid Congress 12th World Orchid Conference ... March 1987, 51 4 1987 Eilau, William World Orchid Conference, Tokyo Tokyo, Japan 13th World Orchid Conference, Auckland, New World Orchid Conference, New 54 2 1990 Eilau, William Zealand Zealand 14th World Orchid Conference, Glascow, 57 3 1993 Hetherington, Ernest World Orchid Conference, scotland Scotland, April 26-May 1, 1993, The 1992 Volume of the Orchid Digest is Dedicated 56 1 1992 in Memoriam to D. George Morel (1926-1973), Hetherington, Ernest history, George Morel The 58 4 1994 1994 Orchid Digest Research Grant Digest Staff 1994 orchid, research, grant 1995 Orchid Digest Dec Dedicated to Herb 59 1 1995 Digest Staff Dedication, Herb Hager Hager 72 2 2008 19th World Orchid Conference Hersch, Helen world orchid conference, 19th 2018 Paphiopedilum Guild and the Second 2018, paphiopedilum guild, second 82 2 2018 International World Slipper Orchid Conference Sorokowsky, David international world slipper orchid, Hilo, Hawaii conference 80 3 2016 22nd World Orchid Conference Pridgeon, Alec 22nd World Orchid Conference 84 4 2020 A Checklist of Phramipedium Species Cervera, Frank checklist, phragmipedium 84 3 2020 A New Color Forma for Vanda curvifolia Koopowitz, Harold vanda, curvifolia, new color form A New Species of Lepanthes (Orchidaceae: Larson, Bruno, Portilla, Jose, Medina 85 2 2021 new species, Lepanthes, Ecuador Pleurothallidinae) from South East Ecuador Hugo A New Species of Pleurothallopsis new species, pleurothallopsis, 82 1 2018 (Epidendreae, Epidendroideae, Orchidaceae): Matthews, Luke M. -

Higher Plants Part A1

APPLICATION FOR CONSENT TO RELEASE A GMO – HIGHER PLANTS PART A1: INFORMATION REQUIRED UNDER SCHEDULE 1 OF THE GENETICALY MODIFIED ORGANISMS (DELIBERATE RELEASE) REGULATIONS 2002 PART 1 General information 1. The name and address of the applicant and the name, qualifications and experience of the scientist and of every other person who will be responsible for planning and carrying out the release of the organisms and for the supervision, monitoring and safety of the release. Applicant: Rothamsted Research, West Common, Harpenden Hertfordshire, AL5 2JQ UK 2. The title of the project. Study of aphid, predator and parasitoid behaviour in wheat producing aphid alarm pheromone PART II Information relating to the parental or recipient plant 3. The full name of the plant - (a) family name, Poaceae (b) genus, Triticum (c) species, aestivum (d) subspecies, N/A (e) cultivar/breeding line, Cadenza (f) common name. Common wheat/ bread wheat 4. Information concerning - (a) the reproduction of the plant: (i) the mode or modes of reproduction, (ii) any specific factors affecting reproduction, (iii) generation time; and (b) the sexual compatibility of the plant with other cultivated or wild plant species, including the distribution in Europe of the compatible species. ai) Reproduction is sexual leading to formation of seeds. Wheat is approximately 99% autogamous under natural field conditions; with self-fertilization normally occurring before flowers open. Wheat pollen grains are relatively heavy and any that are released from the flower remain viable for between a few minutes and a few hours. Warm, dry, windy conditions may increase cross- pollination rates on a variety to variety basis (see also 6 below). -

Index: Sorted by Volume 30-1 Through Volume 85-4

Index: Sorted by Volume 30-1 through Volume 85-4 Volume Issue Year Article Title Author Key Words 30 1 1966 Challenge of the Species Orchids, The Horich, Clarence Kl. species 30 1 1966 Cultural Notes on Houlletia Species Fowlie, J. A. culture, houlletia Great Names — Fred A. Stewart, Inc, 30 1 1966 Eckles, Gloria K. biography, Stewart, Fred A., Earthquake Launches Orchid Career Obscure Species: Rediscovery Notes on 30 1 1966 Fowlie, J. A. houlletia, tigrina, Costa Rica Houlletia tigrina in Costa Rica 30 1 1966 Orchids in the Rose Parade Akers, Sam & John Walters Rose Parade 30 1 1966 Red Cymbidiums Hetherington, Ernest cymbidium, Red 30 1 1966 Shell 345 Soil Fungicide Turner, M. M. & R. Blondeau culture, fungicide 30 1 1966 Study in Beauty - Bifoliates — Part I, A Kirch, William bifoliates, cattleya 30 2 1966 Algae Control in the Greenhouse McCain, A. H. & R. H. Sciaroni culture, algae, greenhouse 30 2 1966 In the Beginning — Cymbidiums and Cattleyas history, cymbidium, cattleya Meristem Culture: Clonal Propagation of 30 2 1966 Morel, Georges M. culture, meristem Orchids odontoglossum, coronarium, 30 2 1966 Odontoglossum coronarium subspecies Horich, Clarence Kl. subspecies 30 2 1966 Orchid Stamps — Johor, Malaysia Choon, Yeoh Bok stamps, Malaysia Some Recent Observations on the Culture of culture, ddontoglossum, 30 2 1966 Fowlie, J. A. Odontoglossum chiriquense chiriquense 30 2 1966 Visit to the Missouri Botanical Garden, A Cutak, Lad botanic Garden, Missouri 30 3 1966 Air Fertilization of Orchids culture, ferilization 30 3 1966 Judging Orchid Flowers judging Just a Big Baby ... Dendrobium superbiens, and 30 3 1966 Nall, Edna dendrobium, superbiens, Australia Australian Species 30 3 1966 Orchid Culture Baldwin, George E. -

Universidad Católica De Santa María Facultad De Ciencias Económico

Universidad Católica de Santa María Facultad de Ciencias Económico Administrativas Escuela Profesional de Ingeniería Comercial ANÁLISIS DE FACTIBILIDAD DE EXPORTACIÓN DE ORQUÍDEAS IN VITRO PERUANAS AL MERCADO DE LOS ÁNGELES EN ESTADOS UNIDOS EN EL 2018 Tesis presentada por las Bachilleres: Paredes del Castillo Estefany Tarqui Cuadros Vanessa Ariane Para optar el título profesional de Ingeniero Comercial con mención en la especialidad de Negocios Internacionales Asesor: Dr. Espinoza Riega, Jorge David Arequipa – Perú 2019 i ii DEDICATORIA A Dios, fuente inagotable de bendiciones para nuestras vidas y principal guía; y a todos aquellos que de alguna u otra manera nos impulsaron a culminar este proyecto con sus valiosos consejos y apoyo brindado. iii AGRADECIMIENTO "Agradecemos a Dios, nuestra fuente de amor, por brindarnos la fe y la fuerza para creer en nosotras mismas y Nuestros Padres, por todo el amor, comprensión y apoyo incondicional”. iv INTRODUCCIÓN El Perú posee un vasto patrimonio vegetal, es uno de los países con mayor biodiversidad del mundo tomando en cuenta su extensión geográfica. Posee más de 4000 especies de orquídeas dentro de su territorio sin embargo debido al acelerado proceso de deforestación motivado por la tala indiscriminada de bosque primario, la explotación del petróleo, la minería y la utilización del suelo destinado a monocultivos ha ocasionado que se pierda gran parte del hábitat natural de estas plantas y por ende la desaparición de un importante número de especies en estado natural. Las orquídeas no se propagan con mayor facilidad en condiciones naturales, es debido a esto que durante muchos años quienes las poseían fueron coleccionistas y científicos en general. -

Phylogenetics and Scanning Electron Microscopy of the Orchid Genus Andinia Sensu Lato

PHYLOGENETICS AND SCANNING ELECTRON MICROSCOPY OF THE ORCHID GENUS ANDINIA SENSU LATO: EVIDENCE FOR TAXONOMIC EXPANSION AND POLLINATION STRATEGIES A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Organismal Biology and Ecology The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Graham S. Frank May/2015 Abstract Andinia Luer (Orchidaceae: Pleurothallidinae) is a small genus from the Andes mountains. Generic circumscriptions within the large subtribe Pleurothallidinae have been under debate as newer molecular evidence aims to correct polyphyletic genera that were created based on potentially homoplasious floral characteristics. Data from the nuclear internally transcribed spacer (ITS) gene region have previously indicated that Andinia should be expanded to include the pleurothallid genera Neooreophilus, Masdevalliantha, and Xenosia. In this study, phylogenetic trees were constructed from an expanded ITS data set, a new data set from the matK gene of the plastid genome, and composite of the two sequences. This broader phylogenetic analysis shows strong support for the monophyly of an expanded Andinia, reinforcing the original recommendation that Andinia be expanded. Additionally, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to image morphological floral characteristics from an array of species spanning the breadth of the analyzed taxa. SEM images suggest multiple pollinator attraction strategies within Andinia sensu lato. Many of the floral characteristics and inferred pollinator attraction strategies are evident elsewhere in Pleurothallidinae, supporting the idea that certain floral characteristics have evolved multiple times and are therefore unreliable for organizing Pleurothallidinae. Acknowledgements: I would like to first thank Dr. Mark Wilson, my advisor, for his guidance, patience, and humor; without him, none of this would have been possible. -

Diagnóstico De La Familia Orchidaceae En México

U ACh 201 Diagnóstico de la La familia Orchidaceae es cosmopolita, tiene representantes 1 en todo el mundo, a excepción de las regiones polares y los familia Orchidaceae en México desiertos extremos. Son abundantes en regiones tropicales y Diagnóstico de la familia Orchidaceae en México subtropicales, aproximadamente a 20° de latitud norte y sur María de los Ángeles Aída Téllez Velasco del Ecuador y pueden encontrarse a cualquier altitud. Cada continente tiene una flora de orquídeas característica, lo cual significa que la evolución de la mayoría de ellas fue posterior a la deriva continental. En el mundo, los países con mayor número de especies de orquídeas son Nueva Guinea, Colombia, Brasil, Borneo y Java. En México, las orquídeas silvestres están distribuidas en los estados de Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Jalisco, More- los, Veracruz y algunas regiones de San Luis Potosí, Michoacán y sur de Puebla. SNIC S SINAREFI Sistema Nacional de Recursos Fitogenéticos para laAlimentación y la Agricultura http://snics.sagarpa.gob.mxwww.sinarefi.org.mx www.chapingo.mx Diagnóstico de la familia Orchidaceae en México (Prosthechea citrina, Prosthechea vitellina, Stanhopea tigrina, Encyclia adenocaula, Laelia speciosa, Laelia gouldiana y Rhynchostele rossii) María de los Ángeles Aída Téllez Velasco Compiladora Textos: Rebeca Alicia Menchaca García, David Moreno Martínez, María de los Ángeles Aída Téllez Velasco, Martha Elena Pedraza Santos y Mario Sumano Gil. Mapas: María de los Ángeles Aída Téllez Velasco Formación y portada: D.G. Miguel Ángel Báez Pérez Primera edición en español: 30 de septiembre de 2011 ISBN: 978-607-12-0206-2 D.R. © Universidad Autónoma Chapingo km 38.5 carretera México-Texcoco Chapingo, Texcoco, Estado de México, CP 56230 Tel: 01 595 95 2 15 00 ext. -

Floral Morphology, Pollination Mechanisms, and Phylogenetics Of

“Floral Morphology, Pollination Mechanisms, and Phylogenetics of Pleurothallis Subgenera Ancipitia and Scopula” A Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Organismal Biology and Ecology, Colorado College BY Katharine Dupree Bachelor of Arts Degree in Biology 16th day of May, 2016 Abstract Pleurothallis is the largest myophilous (fly-pollinated) genus in subtribe Pleurothallidinae. Although many studies show highly specific relationships in pollination systems in the Orchidaceae, our understanding of these relationships in myophilous orchids is almost non-existent (Borba & Semir 2001). This study focuses on the floral micromorphology, specifically the lip and column, of species within subgenera Ancipitia and Scopula. Scanning electron microscopy of the micromorphology of floral structure shows a range of morphology and pollination mechanisms within the two studied subgenera. These include deceit pollination by pseudocopulation and reward pollination. In concert, phylogenetic analysis was performed to determine if a correlation existed between morphology or pollination mechanism and taxonomic groupings. Maximum parsimony trees were produced using ITS and matK sequences for subgenera Ancipitia, Scopula, and Pleurothallis, with species from the genera Laelia, Pabstiella, and Arpophyllum as outgroups. The ITS, matK and combined trees strongly support an Ancipitia/Scopula section within a monophyletic subgenus Pleurothallis. Within this section, both reward and deceit pollination mechanisms are found, meaning they are not restricted to the current taxonomic groupings. Morphological and genetic data therefore support the grouping of subgenera Ancipitia, Scopula, and Pleurothallis into one monophyletic subgenus. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Mark Wilson, my advisor, for his guidance, inspiration, and encouragement. I would also like to thank former students for sequence contributions, Graham Frank for establishing protocols, and the Colorado College Organismal Biology and Ecology Department for funding. -

Sample Pages

THE BOOK OF ORCHIDS A LIFE-SIZE GUIDE TO SIX HUNDRED SPECIES FROM AROUND THE WORLD MARK CHASE AND MAARTEN CHRISTENHUSZ FOREWORD TOM MIRENDA THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago PROFESSOR MARK CHASE is a senior research scientist at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He is also a visiting professor at the School of Biological Sciences CONTENTS at the University of London and at the School of Plant Biology at the University of Western Australia, and a fellow of the Linnean Society and the Royal Society. He co-edited Genera Orchidacearum and has contributed to more than 500 Foreword 6 publications on plant science. Introduction DR. MAARTEN CHRISTENHUSZ is a botanist-consultant who has worked for the 8 Finnish Museum of Natural History in Helsinki, the Natural History Museum Orchid evolution 12 (London) and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Maarten was initiator of the journal Phytotaxa and is deputy editor of the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Pollination 14 Society. He has written about a hundred scientific and popular publications. Symbiotic relationships 18 Uses of orchids 20 The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 This book was conceived, Orchidelirium 26 © The Ivy Press Limited 2017 designed, and produced by All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ivy Press reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Publisher SUSAN KELLY permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical Creative Director MICHAEL WHITEHEAD The orchids 30 articles and reviews. For more information, contact the Editorial Director TOM KITCH University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL Art Director WAYNE BLADES 60637. -

By Volume 30-1 Through Volume 84-4

Index: Sorted by Volume 30-1 through Volume 84-4 Volume Issue Year Article Title Author Key Words 30 1 1966 Challenge of the Species Orchids, The Horich, Clarence Kl. species 30 1 1966 Cultural Notes on Houlletia Species Fowlie, J. A. culture, houlletia Great Names — Fred A. Stewart, Inc, Earthquake 30 1 1966 Eckles, Gloria K. biography, Stewart, Fred A., Launches Orchid Career Obscure Species: Rediscovery Notes on Houlletia 30 1 1966 Fowlie, J. A. houlletia, tigrina, Costa Rica tigrina in Costa Rica 30 1 1966 Orchids in the Rose Parade Akers, Sam & John Walters Rose Parade 30 1 1966 Red Cymbidiums Hetherington, Ernest cymbidium, Red 30 1 1966 Shell 345 Soil Fungicide Turner, M. M. & R. Blondeau culture, fungicide 30 1 1966 Study in Beauty - Bifoliates — Part I, A Kirch, William bifoliates, cattleya 30 2 1966 Algae Control in the Greenhouse McCain, A. H. & R. H. Sciaroni culture, algae, greenhouse 30 2 1966 In the Beginning — Cymbidiums and Cattleyas history, cymbidium, cattleya 30 2 1966 Meristem Culture: Clonal Propagation of Orchids Morel, Georges M. culture, meristem odontoglossum, coronarium, 30 2 1966 Odontoglossum coronarium subspecies Horich, Clarence Kl. subspecies 30 2 1966 Orchid Stamps — Johor, Malaysia Choon, Yeoh Bok stamps, Malaysia Some Recent Observations on the Culture of culture, ddontoglossum, 30 2 1966 Fowlie, J. A. Odontoglossum chiriquense chiriquense 30 2 1966 Visit to the Missouri Botanical Garden, A Cutak, Lad botanic Garden, Missouri 30 3 1966 Air Fertilization of Orchids culture, ferilization 30 3 1966 Judging Orchid Flowers judging Just a Big Baby ... Dendrobium superbiens, and 30 3 1966 Nall, Edna dendrobium, superbiens, Australia Australian Species 30 3 1966 Orchid Culture Baldwin, George E.