Jews, Ethnicity and Identity in Early Modern Hamburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Für Alle Herzens- Angelegenheiten. Außer Liebes- Kummer

Cardio_Praxisfolder2013_v6.qxd 31.01.2013 17:09 Uhr Seite 1 Überall in Hamburg. Herzlich willkommen! PRAXEN WANDSBEK PRAXIS RAHLSTEDT Schloßgarten 3 Hagenower Straße 5 22041 Hamburg 22143 Hamburg Tel.: +49. (0)40. 68 28 06-0 Tel.: +49. (0)40. 70 70 80 8-0 Dr. med. Heinz-Hubert Breuer Lutz Herrmann Internist, Kardiologe und Angiologe Internist und Kardiologe Universitäres Bramfeld Dr. med. Jan Noack Swetlana Pak Internist und Kardiologe Internistin und Kardiologin Herzzentrum Rahlstedt Hamburg Dr. med. Ekkehard Schmidt Internist und Kardiologe PRAXIS HARBURG Harvestehude Wandsbek PD Dr. med. Dirk Walter Am Wall 1 Internist, Kardiologe und Angiologe 21073 Hamburg Wedel Dr. Kai Augustin Tel.: +49. (0)40. 70 70 81 8-0 AK Wandsbek Internist und Kardiologe Dr. med. Rudolf Rüppel Mehmet Ergin Internist und Kardiologe Internist und Kardiologe Dr. med. Georg Schmidt Blankenese Internist, Kardiologe und Angiologe Schloßgarten 7 22041 Hamburg Dr. med. Marietta v. Tschirschnitz Internistin und Kardiologin Tel.: +49. (0)40. 68 28 06-0 Harburg Dr. med. Martin Kindel PRAXIS HARVESTEHUDE Internist und Kardiologe Hallerstraße 6 Irmgard Hasfeld 20146 Hamburg Internistin Tel.: +49. (0)40. 44 52 02 Kinderkardiologie* Dr. med. Jan Noack Wandsbeker Marktstraße 69–71 Internist und Kardiologe 22041 Hamburg Tel.: +49. (0)40. 68 24 00 PRAXIS BRAMFELD Dr. med. Christian Beyer Hellbrookkamp 33–35 Kinder- und Jugendkardiologe 22177 Hamburg Sie finden uns an 10 Standorten in ganz Hamburg. Tel.: +49. (0)40. 6173 74 Das Cardiologicum Hamburg ist eine Gemeinschaftspraxis mit PRAXIS BLANKENESE Darüber hinaus stehen uns 2 Herzkathetherlabore Dr. med. Judith Licht dem Schwerpunkt Herz-, Kreislauf- und Gefäßerkrankungen. Blankeneser Bahnhofstraße 21–23 Internistin und Kardiologin Für alle Herzens- zur Verfügung. -

(Munich-Augsburg-Rothenburg-Wurzburg-Wiesbaden) Tour Code: DAECO10D9NBAV Day 1: Munich Arrival Munich Airport Welcome to Munich

(Munich-Augsburg-Rothenburg-Wurzburg-Wiesbaden) Tour Code: DAECO10D9NBAV Day 1: Munich Arrival Munich airport Welcome to Munich. Take public transportation to your hotel on your own. Suggestions: Visit one of the many beer pubs with local brewed beer and taste the Bavarian sausage Accommodation in Munich. Day 2: Munich 09:30 hrs Meet your English speaking guide at the hotel lobby for a half day city tour. No admission fee included. Optional full day tour Neuschwanstein castle(joint tour daily excursion bus tour,10.5 hrs). 08:30 hrs: Bus transfer from Munich main station. Admission fee for the castle has to be paid on the bus extra. (In case of Optional Tour Neuschwanstein, half day sightseeing tour of Munich can be done on the 3RD day in the morning). Accommodation in Munich. Copyright:GNTB Day 3: Munich - Augsburg (Historic Highlight City) Transfer by train to Augsburg on your own Suggestions: Visit the Mozart House and the famous Fugger houses. Try the local Swabian cuisine at the restaurant <Ratskeller> or take a refreshing beer in one of the beer gardens in the city. Accommodation in Augsburg Copyright: Regio Augsburg Tourismus GmbH Day 4: Augsburg 09.30 hrs . Meet your English speaking guide at the hotel lobby and start half day city tour of Augsburg. (2 hrs). No admission fee included. Accommodation in Augsburg. Copyright: Stadt Augsburg Day 5: Augsburg - Rothenburg (Romantic Road City) Leave the hotel by train to the romantic city of Rothenburg. At 14:00 hrs, meet your English speaking guide in the lobby of the hotel and start your half day city tour including St. -

KAS International Reports 10/2015

38 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 10|2015 MICROSTATE AND SUPERPOWER THE VATICAN IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Christian E. Rieck / Dorothee Niebuhr At the end of September, Pope Francis met with a triumphal reception in the United States. But while he performed the first canonisation on U.S. soil in Washington and celebrated mass in front of two million faithful in Philadelphia, the attention focused less on the religious aspects of the trip than on the Pope’s vis- its to the sacred halls of political power. On these occasions, the Pope acted less in the role of head of the Church, and therefore Christian E. Rieck a spiritual one, and more in the role of diplomatic actor. In New is Desk officer for York, he spoke at the United Nations Sustainable Development Development Policy th and Human Rights Summit and at the 70 General Assembly. In Washington, he was in the Department the first pope ever to give a speech at the United States Congress, of Political Dialogue which received widespread attention. This was remarkable in that and Analysis at the Konrad-Adenauer- Pope Francis himself is not without his detractors in Congress and Stiftung in Berlin he had, probably intentionally, come to the USA directly from a and member of visit to Cuba, a country that the United States has a difficult rela- its Working Group of Young Foreign tionship with. Policy Experts. Since the election of Pope Francis in 2013, the Holy See has come to play an extremely prominent role in the arena of world poli- tics. The reasons for this enhanced media visibility firstly have to do with the person, the agenda and the biography of this first non-European Pope. -

Ohlstedter Straße – Verfügung Einer Widmung Im Bezirk Bergedorf

Amtl. Anz. Nr. 21 Dienstag, den 16. März 2021 387 Widmung von Zum einen beabsichtigt das Bezirksamt Bergedorf die Aufstellung von zwei Bebauungsplänen, für die die folgen- Wegeflächen im Bezirk Wandsbek den Bezeichnungen vorgesehen sind: – Ohlstedter Straße – Billwerder 30/Bergedorf 120/Neuallermöhe 2 Nach § 6 des Hamburgischen Wegegesetzes in der Fas- (Oberbillwerder) sung vom 22. Januar 1974 (HmbGVBl. S. 41, 83) mit Ände- und rungen wird die im Bezirk Wandsbek, Gemarkung Ohl- stedt, Ortsteil 523, belegene Wegefläche Ohlstedter Straße Lohbrügge 95/Bergedorf 121/Neuallermöhe 3 (Flurstück 165 teilweise), von Brandheide bis Ellerbrooks- (Anbindung Oberbillwerder im Nordosten und Osten). wisch verlaufend, mit sofortiger Wirkung dem allgemeinen Verkehr gewidmet. Bebauungsplangebiete: Nach § 8 in Verbindung mit § 6 des Hamburgischen Wegegesetzes in der Fassung vom 22. Januar 1974 (Hmb- GVBl. S. 41, 83) mit Änderungen wird die im Bezirk Wandsbek, Gemarkung Ohlstedt, Ortsteil 523, belegene Verbreiterungsfläche Ohlstedter Straße (Flurstück 165 teil- weise), vor den Häusern Nummern 13 bis 21 verlaufend, mit sofortiger Wirkung dem allgemeinen Verkehr gewid- met. Die urschriftliche Verfügung mit Lageplan kann beim Bezirksamt Wandsbek, Fachamt Management des öffentli- chen Raumes, Am Alten Posthaus 2, 22041 Hamburg, ein- gesehen werden. Rechtsbehelfsbelehrung: Gegen diese Verfügung kann innerhalb eines Monats nach Bekanntgabe beim Bezirksamt Wandsbek, Fachamt Management des öffentlichen Raumes, Postfach 70 21 41, 22021 Hamburg, Widerspruch eingelegt werden. Zum anderen beabsichtigen die Behörde für Stadtent- wicklung und Wohnen bzw. die Behörde für Umwelt, Hamburg, den 24. Februar 2021 Klima, Energie und Agrarwirtschaft den Flächennutzungs- Das Bezirksamt Wandsbek plan bzw. das Landschaftsprogramm im Parallelverfahren Amtl. Anz. S. 387 zu ändern. Die Bezeichnung der Änderungen lautet „Misch- nutzung, Wohnen und Grün nördlich der Bahntrasse in Billwerder und Bergedorf“. -

Biography CHARLOTTE C. BAER, MD October 11, 1908 - August 15, 1973 Dr

Biography CHARLOTTE C. BAER, MD October 11, 1908 - August 15, 1973 Dr. Charlotte Baer was born into a medical family of Wiesbaden, Germany where her father was a practicing physician. He served with distinction in the medical corps of the German Army in World War I and was decorated for his services. It was perhaps natural that his daughter, an only child, would attend medical school. Her father saw to it that at an appropriate time in her life she also attended a cooking school, which, no doubt, accounted for her excellence as a cook, a trait which continued throughout her lifetime. In the European tradition, she attended medical schools throughout Europe and, more than that, lived for varying periods of time in countries other than Germany, giving her considerably more than an elementary knowledge of foreign languages. By the time of her arrival in the United States, she could converse not only in German, but also in English, French, and Italian. As the result of her medical studies, she received MD degrees from the Goethe Medical School Frankfurt am Main and the University of Berne, Switzerland. Throughout her college and medical school years, she found time to continue her enthusiasm for swimming and, in fact, became the intercollegiate breaststroke-swimming champion of Europe. By the time of the Berlin Olympics, she was not permitted to compete for the German team by the Nazi regime because of her Jewish heritage. She did, however, attend the Olympic Games in Berlin and recounted with great pleasure seeing Jesse Owens receive his three gold medals for track and field events withAdolph Hitler being among those present in the stadium. -

Information Contact Details Hamburg District Offices - Departments for Foreigners

Information Contact Details Hamburg District Offices - Departments for Foreigners Which Foreigners Department is responsible for me? You can easily identify the District Office in charge of your application for a residence permit (or its extension) online while using the Hamburg Administration Guide („Behördenfinder der Stadt Hamburg“). (1) Call up the Hamburg Administration Guide: https://www.hamburg.de/behoerdenfinder/hamburg/11253817/ (2) Enter your registered address (street name and house number) in Hamburg. (3) Press the red button („Weiter“). Now the Hamburg Administration Guide will show you the relevant department’s contact details and opening hours. Qualified professionals and managers, students and their families can also contact the Hamburg Welcome Center. Information Contact Details Hamburg District Offices - Departments for Foreigners District Office (= „Bezirksamt“) Hamburg-Mitte Customer Service Center (= „Kundenzentrum“) Hamburg-Mitte Department for Foreigners Affairs (= „Fachbereich Ausländerangelegenheiten“) Klosterwall 2 (Block A), 20095 Hamburg Phone: 040 / 428 54 – 1903 E-Mail: [email protected] District Office Hamburg-Mitte Customer Service Center Billstedt Department for Foreigners Affairs Öjendorfer Weg 9, 22111 Hamburg Phone: 040 / 428 54 – 7455 oder 040 / 428 54 – 7461 E-Mail: [email protected] District Office Hamburg-Mitte Hamburg Welcome Center Adolphsplatz 1, 20457 Hamburg Phone: 040 / 428 54 – 5001 E-Mail: [email protected] -

Biographical Motivations of Pilgrims on the Camino De Santiago

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Volume 7 Issue 2 Special Issue : Volume 1 of Papers Presented at 10th International Religious Article 3 Tourism and Pilgrimage Conference 2018, Santiago de Compostela 2019 Biographical Motivations of Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago Christian Kurrat FernUniversität in Hagen (Germany), [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Kurrat, Christian (2019) "Biographical Motivations of Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago," International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Vol. 7: Iss. 2, Article 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.21427/06p1-9w68 Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol7/iss2/3 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. © International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage ISSN : 2009-7379 Available at: http://arrow.dit.ie/ijrtp/ Volume 7(ii) 2019 Biographical Motivations of Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago Christian Kurrat, Ph.D. FernUniversität in Hagen (Germany) [email protected] The question of what leads people from a biographical perspective to go on pilgrimage has been a research object in the Department of Sociology at the FernUniversität in Hagen, Germany. This qualitative study examines the biographical constellations which have led to the decision to go on pilgrimage and therefore a typology of biographical motivations was developed. To achieve the aim of a typology, methods of qualitative research were used. The database consists of narrative interviews that were undertaken mostly with German pilgrims. The life stories of the pilgrims were analysed with Grounded Theory Methodology and made into a typology of five main types of pilgrims: balance pilgrim, crisis pilgrim, time-out pilgrim, transitional pilgrim, new start pilgrim. -

By Car Leave the Motorway A7 at the Exit Schnelsen-Nord Heading Ring

Your route to Lufthansa Technical Training in Hamburg. Lufthansa Basis, Weg beim Jäger 193, D-22335 Hamburg, Gebäude 125, 2.Etage By car Leave the motorway A7 at the exit Schnelsen-Nord heading Ring 3 towards “Flughafen/Luftwerft” By following the signs "Luftwerft" you arrive at the road named "Weg beim Jäger". Continue driving on this road until you reach the Lufthansa Base Hamburg (Lufthansa Basis Hamburg) on your right hand. Then please turn right and drive to the visitor reception ("Besucherempfang"), where you will receive a voucher which permits you free parking at our car park (only for the first day of your course or your visit). If you are staying for more than one day we are not able to obtain free parking permission – therefore we ask you to use the public transport or the shuttle service of the hotel. By train You can travel by long-distance train to Hamburg Central Station. Timetable information and tickets are available from German Rail. To get to the airport you can use the direct train connection (S1 to Poppenbüttel/Airport) between the airport and the central station. You will obtain timetable information from the city transport authority Hamburger Verkehrsverbund: www.hvv.de. After arriving at Hamburg Airport please head for the exit of Terminal 2 (Arrival Level). There is a bus stop located at section B, between Terminal 1 and 2, where a free shuttle bus stops (Holiday-Shuttle P8/P9). Leave the bus at "Lufthansa Basis/Haupteingang" (Lufthansa Base Main Entrance). There you will find our Visitor's Reception. -

Hamburg Nord (Barmbek Süd, Barmbek Nord) Hamburg

ALLGEMEINE VERKEHRSHINWEISE, HAMBURG NORD/WANDSBEK (BAMBERK NORD, HAMBURG WANDSBEK (FARMSEN, BERNE, RAHLS- BESONDERHEITEN Durch straßenverkehrsbehördliche Anordnungen ist die gesamte Rennstre- Ost–West–Verbindung cke für die Dauer der Veranstaltung voll gesperrt. Durch örtliche Umleitun- STEILSHOOP, BRAMFELD, FARMSEN–BERNE) TEDT, VOLKSDORF) Der Durchgangsverkehr auf der B4 (Budapester Straße – Ludwig–Erhard– gen und Sperrungen kann es auch abseits der Rennstrecke zu erheblichen Gesperrte Straßen: Sperrzeiten: 07:30 – 12:15 Uhr Straße) wird aufgrund von Sperrungen am Millerntorplatz/Millerntordamm Zeitverzögerungen im Verkehrsablauf kommen. Die Polizei empfiehlt, die Saarlandstraße > Alte Wöhr > Langenfort > Rümkerstraße > Steilshooper im Zeitraum ca. 07:30 bis 16:30 Uhr nicht möglich sein. GESPERRTE STRASSEN: Veranstaltung über die Autobahnen und den Ring 2 sowie nördlich über Allee > Am Luisenhof > August–Krogmann–Straße>Berner Heerweg Ausweichempfehlung aus Richtung Osten: Von der A1 / A255 (neue Elb- Berner Heerweg > Berner Brücke > Kriegkamp > Saseler Straße > Jesselallee den Ring 3 weiträumig zu umfahren. Es wird dringend angeraten, U– und brücken) über den Heidenkampsweg auf den Ring 2 ausweichen und > Nordlandweg > Spitzbergenweg > Meiendorfer Straße S–Bahnen zu benutzen. Über die Rundfunksender informiert die Polizei SPERRZEITEN: ca. 07:30 – 12:00 Uhr dann nach Möglichkeit die frei befahrbaren Straßen nördlich der Alster während der Veranstaltung über die aktuelle Verkehrslage. Die Polizei wird DURCHLAUFZEITEN: DURCHLAUFZEITEN: -

Table of Contents

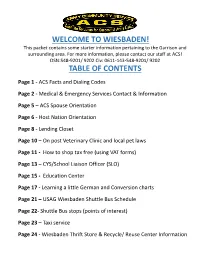

WELCOME TO WIESBADEN! This packet contains some starter information pertaining to the Garrison and surrounding area. For more information, please contact our staff at ACS! DSN:548-9201/ 9202 Civ: 0611-143-548-9201/ 9202 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 - ACS Facts and Dialing Codes Page 2 - Medical & Emergency Services Contact & Information Page 5 – ACS Spouse Orientation Page 6 - Host Nation Orientation Page 8 - Lending Closet Page 10 – On post Veterinary Clinic and local pet laws Page 11 - How to shop tax free (using VAT forms) Page 13 – CYS/School Liaison Officer (SLO) Page 15 - Education Center Page 17 - Learning a little German and Conversion charts Page 21 – USAG Wiesbaden Shuttle Bus Schedule Page 22- Shuttle Bus stops (points of interest) Page 23 – Taxi service Page 24 - Wiesbaden Thrift Store & Recycle/ Reuse Center Information Follow USAG Wiesbaden on Facebook for up to date information concerning COVID19. https://www.facebook.com/usagwiesbaden/ This is the official page for the Wiesbaden Military Community updates managed by the U.S. Army Garrison Wiesbaden Public Affairs Office. Information Links: USAG Wiesbaden Garrison website: https://home.army.mil/wiesbaden/ USAG Wiesbaden COVID19 Information: https://home.army.mil/wiesbaden/ index.php/coronavirus USAG Wiesbaden Family and MWR website: https://wiesbaden.armymwr.com/ USAG Wiesbaden AFN website: https://www.afneurope.net/Stations/Wiesbaden/ ACS Facts at a Glance Location: Mississippi Straβe 22 Bldg 07790, on Hainerberg Housing Phone: DSN (314)548-9201/ 9202 CIV 0611-143-548-9201/ 9202 Operating hours: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday appointments only until 1 p.m. -

Stadtteil Stations-Nr. Altona Alsenstraße

Stationsübersicht (Stadtteil) Stand: März 2016 Station (aktiv) Stadtteil Stations-Nr. Altona Alsenstraße / Düppelstraße Altona 2134 Bahnhof Altona Ost / Max-Brauer-Allee Altona 2121 Bahnhof Altona West / Busbahnhof Altona 2122 Bahrenfelderstraße / Völckersstraße Altona 2126 Chemnitzstraße / Max-Brauer-Allee Altona 2116 Eulenstraße / Große Brunnenstraße Altona 2124 Fischers Allee / Bleickenallee (Mittelinsel) Altona 2125 Fischmarkt / Breite Straße Altona 2112 Große Bergstraße / Jessenstraße Altona 2115 Königstraße / Struenseestraße Altona 2113 Thadenstraße / Holstenstraße Altona-Altstadt 2119 Van-der-Smissen-Straße / Großbe Elbstraße (ab April 2016) Altona-Altstadt 2117 Friedensallee / Hegarstraße Bahrenfeld 2090 Notkestraße / DESY Bahrenfeld 2070 Dürerstraße / Beseler Platz Groß Flottbek 2085 Elbchaussee / Teufelsbrück Nienstedten 2050 Ohnhorststraße / Klein Flottbek Osdorf 2040 Osdorfer Landstraße / Elbe-Einkaufszentrum Osdorf 2031 Paul-Ehrlich-Straße / Asklepios Klinikum Altona Othmarschen 2075 Große Rainstraße / Ottenser Hauptstraße Ottensen 2127 Hohenzollernring / Friedensallee Ottensen 2129 Neumühlen / Övelgönne Ottensen 2151 Ottenser Marktplatz / Museumsstraße Ottensen 2114 Neuer Pferdemarkt / Beim Grünen Jäger Sternschanze 2131 Schulterblatt / Eifflerstraße Sternschanze 2132 Sternschanze / Eingang Dänenweg Sternschanze 2133 Bergedorf S-Bahnhof Allermöhe / Walter-Rudolphi-Weg (ab April 2016) Allermöhe S-Bahnhof Nettelnburg / Friedrich-Frank-Bogen (ab April 2016) Bergedorf Vierlandenstraße / Johann-Adolf-Hasse-Platz (ab April 2016) -

Information Note Event: Wiesbaden III: Governance

Information Note1 Event: Wiesbaden III: Governance and Compliance Management Conference on Resolution 1540 (2004) Organizer: Government of Germany in cooperation with the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) and the European Commission’s Programme “Outreach in Export Controls of Dual-Use Items” (implemented by the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control, BAFA) Date and venue: 20-21 November 2014, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Participants: States: Germany, Malaysia, United States of America International and Regional Organizations: 1540 Committee and expert, UNODA, UN Panel of Experts: Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1737 (2006), Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), World Customs Organization (WCO), INTERPOL, European Commission, CARICOM Industry: AREVA, International Federation of Freight Forwarders Associations (FIATA), Ericsson AB Sweden, International Federation of Biosafety Associations (IFBA), Biosafety Association of Central Asia and Caucasus (BACAC), Compliance and Capacity International (LLC), Rolls-Royce plc, Asia-Pacific Biosafety Association, General Electric, Royal Philips, CISTEC, Commerzbank AG, German Aerospace Industry (BDLI), World Nuclear Association, Korea Strategic Trade Institute, Nuclear Power Plant Exporters' Principles of Conduct, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Verband der Chemischen Industrie, Compliance Academy, International Centre for Chemical Safety and Security, Indian Chemical Council, Julius Kriel Consultancy CC, Leibniz Institut DSMZ, Infineon Technologies AG, Lufthansa Cargo AG, Merck KGaA, African Biological Safety Association Non-Governmental Organizations and Academia: SIPRI, Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control, University of Georgia (USA), Center for Interdisciplinary Compliance Research at the European University, The Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis (New Delhi), Stimson Center, Monterey Institute of International Studies (Center for Non- Proliferation Studies), Kings College (London) 1 For information - not an official report.