Reproduction Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZOO 435 Lecture - General Characteristics of Extant Birds

ZOO 435 Lecture - General Characteristics of Extant Birds Forelimbs are wings (in all birds); most can fly Feathers and leg scales (epidermal structures) No sweat glands Uropygial gland present in most Rudimentary pinna (fleshy ear) Skeleton fully ossified; air sacs in bones; strutting for strength Cervical vertebrae have saddle-shaped articular surface – very flexible Single occipital condyle (flexible) Jaws covered by beak (keratinized sheath) No teeth Well developed brain and nervous system Optic lobes and cerebellum very well-developed Excellent eyesight – can see color, UV, and polarized light o Golden Eagle can see a rabbit two miles away; 1500 feet for people Poor sense of taste and smell (with some exceptions) 12 pairs of cranial nerves (just like mammals) 4-chambered heart; Right aortic arch (IV) persists Reduced renal portal system (Blood from the posterior part of the body flows into the renal portal veins, which pass into the caudal vena cava. The renal portal system is found only in fishes, amphibians, reptiles and birds. Thus, mammals have no renal portal system. All that remains in mammals is the azygous vein, which is an unpaired vein that drains most of the intercostal space on both sides of the mammalian thorax.) Nucleated red blood cells Crop – diverticulum of the esophagus (allows ingestion of food which can be stored until a safe place is found for digestion) Proventriculus – distal portion of the stomach (closer to mouth); initiates digestion; Ventriculus (gizzard) – proximal portion of the stomach (farther from mouth); muscular walls to grind and crush, often aided by sand or gravel Air sacs among viscera and in skeleton Voice box = syrinx; located at proximal end of trachea, at junction with bronchi Cloaca; no bladder; semi-solid urine; nitrogenous waste = uric acid Female with only left ovary and oviduct (exceptions, e.g. -

![Oogenesis [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2902/oogenesis-pdf-452902.webp)

Oogenesis [PDF]

Oogenesis Dr Navneet Kumar Professor (Anatomy) K.G.M.U Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Oogenesis • Development of ovum (oogenesis) • Maturation of follicle • Fate of ovum and follicle Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Oogenesis • Site – ovary • Duration – 7th week of embryo –primordial germ cells • -3rd month of fetus –oogonium • - two million primary oocyte • -7th month of fetus primary oocyte +primary follicle • - at birth primary oocyte with prophase of • 1st meiotic division • - 40 thousand primary oocyte in adult ovary • - 500 primary oocyte attain maturity • - oogenesis completed after fertilization Dr Navneet Kumar Dr NavneetKumar Professor Professor (Anatomy) Anatomy KGMU Lko K.G.M.U Development of ovum Oogonium(44XX) -In fetal ovary Primary oocyte (44XX) arrest till puberty in prophase of 1st phase meiotic division Secondary oocyte(22X)+Polar body(22X) 1st phase meiotic division completed at ovulation &enter in 2nd phase Ovum(22X)+polarbody(22X) After fertilization Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Dr Navneet Kumar Dr ProfessorNavneetKumar (Anatomy) Professor K.G.M.UAnatomy KGMU Lko Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Maturation of follicle Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Maturation of follicle Primordial follicle -Follicular cells Primary follicle -Zona pallucida -Granulosa cells Secondary follicle Antrum developed Ovarian /Graafian follicle - Theca interna &externa -Membrana granulosa -Antrial -

Sex-Specific Spawning Behavior and Its Consequences in an External Fertilizer

vol. 165, no. 6 the american naturalist june 2005 Sex-Specific Spawning Behavior and Its Consequences in an External Fertilizer Don R. Levitan* Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, a very simple way—the timing of gamete release (Levitan Tallahassee, Florida 32306-1100 1998b). This allows for an investigation of how mating behavior can influence mating success without the com- Submitted October 29, 2004; Accepted February 11, 2005; Electronically published April 4, 2005 plications imposed by variation in adult morphological features, interactions within the female reproductive sys- tem, or post-mating (or pollination) investments that can all influence paternal and maternal success (Arnqvist and Rowe 1995; Havens and Delph 1996; Eberhard 1998). It abstract: Identifying the target of sexual selection in externally also provides an avenue for exploring how the evolution fertilizing taxa has been problematic because species in these taxa often lack sexual dimorphism. However, these species often show sex of sexual dimorphism in adult traits may be related to the differences in spawning behavior; males spawn before females. I in- evolutionary transition to internal fertilization. vestigated the consequences of spawning order and time intervals One of the most striking patterns among animals and between male and female spawning in two field experiments. The in particular invertebrate taxa is that, generally, species first involved releasing one female sea urchin’s eggs and one or two that copulate or pseudocopulate exhibit sexual dimor- males’ sperm in discrete puffs from syringes; the second involved phism whereas species that broadcast gametes do not inducing males to spawn at different intervals in situ within a pop- ulation of spawning females. -

Needham Notes

Lesson 26 Lesson Outline: Exercise #1 - Basic Functions Exercise #2 - Phylogenetic Trends Exercise #3 - Case Studies to Compare • Reproductive Strategies- Energy Partitioning • External versus Internal Fertilization • Sexual Dimorphism o Functional Characteristics o Aids to Identification o Copulatory Organs • Timing - Copulation, Ovulation, Fertilization, Development Objectives: Throughout the course what you need to master is an understanding of: 1) the form and function of structures, 2) the phylogenetic and ontogenetic origins of structures, and 3) the extend to which various structures are homologous, analogous and/or homoplastic. At the end of this lesson you should be able to: Describe the advantages and disadvantages of internal and external fertilization Describe sexual dimorphism and the selection pressures that lead to it Describe the trends seen in the design of copulatory organs Describe the various forms of reproductive strategy for delaying development of the fertilized egg and the selective advantage of them References: Chapter 15: 351-386 Reading for Next Lesson: Chapter 16: 387- 428 Exercise #1 List the basic functions of the urogenital system: The urinary system excretes the waste products of cellular digestion, ions, amino acids, salts, etc. It also plays a key role in water balance along with numerous other structures in different species living in different environments (i.e. gills, skin, salt glands). The primary function of the system is to give rise to offspring, - to reproduce. Exercise #2 Describe the evolutionary trends that we see in the urogenital systems of the different vertebrate groups: The phylogenetic trends that we see throughout the chordates were covered in detail in lectures (lecture 31 and 32) and are summarized schematically in the next figures: Exercise #3 – Comparisons – Case 1 Reproductive Strategies - Energy Partitioning Some would argue that the primary reason that organisms exist is to reproduce and make more organisms. -

Reproductive Ecology & Sexual Selection

Reproductive Ecology & Sexual Selection REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY REPRODUCTION & SEXUAL SELECTION • Asexual • Sexual – Attraction, Courtship, and Mating – Fertilization – Production of Young The Evolutionary Enigma of Benefits of Asex Sexual Reproduction • Sexual reproduction produces fewer reproductive offspring than asexual reproduction, a so-called reproductive handicap 1. Eliminate problem to locate, court, & retain suitable mate. Asexual reproduction Sexual reproduction Generation 1 2. Doubles population growth rate. Female Female 3. Avoid “cost of meiosis”: Generation 2 – genetic representation in later generations isn't reduced by half each time Male 4. Preserve gene pool adapted to local Generation 3 conditions. Generation 4 Figure 23.16 The Energetic Costs of Sexual Reproduction Benefits of Sex • Allocation of Resources 1. Reinforcement of social structure 2. Variability in face of changing environment. – why buy four lottery tickets w/ the same number on them? Relative benefits: Support from organisms both asexual in constant & sexual in changing environments – aphids have wingless female clones & winged male & female dispersers – ciliates conjugate if environment is deteriorating Heyer 1 Reproductive Ecology & Sexual Selection Simultaneous Hermaphrodites TWO SEXES • Advantageous if limited mobility and sperm dispersal and/or low population density • Guarantee that any member of your species encountered is the • Conjugation “right” sex • Self fertilization still provides some genetic variation – Ciliate protozoans with + & - mating -

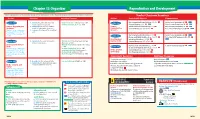

Chapter 38: Reproduction and Development Computer Test Bank Cryopreservation

Chapter 38 Organizer Reproduction and Development Refer to pages 4T-5T of the Teacher Guide for an explanation of the National Science Education Standards correlations. Teacher Classroom Resources Activities/FeaturesObjectivesSection MastersSection TransparenciesReproducible Reinforcement and Study Guide, pp. 167-168 L2 Section Focus Transparency 93 L1 ELL Section 38.1 1. Identify the parts of the male and Inside Story: Sex Cell Production, p. 1033 Section 38.1 female reproductive systems. Problem-Solving Lab 38-1, p. 1035 Concept Mapping, p. 38 L3 ELL Basic Concepts Transparency 74 L2 ELL Human Reproductive 2. Summarize the negative feedback Human Critical Thinking/Problem Solving, p. 38 L3 Basic Concepts Transparency 75 L2 ELL Systems control of reproductive hormones. Reproductive Content Mastery, pp. 185-186, 188 L1 Reteaching Skills Transparency 55 L1P ELL National Science Education 3. Sequence the stages of the menstrual Systems P P cycle. Standards UCP.1-3, UCP.5; P C.1, C.5; F.1 (2 sessions, 11/ P 2 Reinforcement and Study Guide, p. 169 L2 P Section Focus Transparency 94 L1 ELLP blocks) Section 38.2 P LS BioLab and MiniLab Worksheets, pp. 169-170 L2 Reteaching Skills Transparency 56a,P 56b L1 LS P LS Development Laboratory Manual, pp. 277-284 L2 ELL P Before Birth LS Section 38.2 4. Summarize the events during each MiniLab 38-1: Examining Sperm and Egg Content Mastery, pp. 185,LS 187-188 L1 LS P LS trimester of pregnancy. Attraction, p. 1038 LS Development Before MiniLab 38-2: Making a Graph of Fetal Size, P LS P Reinforcement and Study Guide, p. -

Coral Reproduction

UNIT 5: CORAL REPRODUCTION CORAL REEF ECOLOGY CURRICULUM This unit is part of the Coral Reef Ecology Curriculum that was developed by the Education Department of the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. It has been designed for secondary school students, but can be adapted for other uses. The entire curriculum can be found online at lof.org/CoralReefCurriculum. Author and Design/Layout: Amy Heemsoth, Director of Education Editorial assistance provided by: Andrew Bruckner, Ken Marks, Melinda Campbell, Alexandra Dempsey, and Liz Rauer Thompson Illustrations by: Amy Heemsoth Cover Photo: ©Michele Westmorland/iLCP ©2014 Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise noted, photos are property of the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation and authors disclaim any liability for injury or damage related to the use of this curriculum. These materials may be reproduced for education purposes. When using any of the materials from this curriculum, please include the following attribution: Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation Coral Reef Ecology Curriculum www.lof.org The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation (KSLOF) was incorporated in California as a 501(c)(3), public benefit, Private Operating Foundation in September 2000. The Living Oceans Foundation is dedicated to providing science-based solutions to protect and restore ocean health through research, outreach, and education. The educational goals of the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation -

The Reproductive System

PowerPoint® Lecture Slides prepared by Meg Flemming Austin Community College C H A P T E R 19 The Reproductive System © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 19 Learning Outcomes • 19-1 • List the basic components of the human reproductive system, and summarize the functions of each. • 19-2 • Describe the components of the male reproductive system; list the roles of the reproductive tract and accessory glands in producing spermatozoa; describe the composition of semen; and summarize the hormonal mechanisms that regulate male reproductive function. • 19-3 • Describe the components of the female reproductive system; explain the process of oogenesis in the ovary; discuss the ovarian and uterine cycles; and summarize the events of the female reproductive cycle. © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 19 Learning Outcomes • 19-4 • Discuss the physiology of sexual intercourse in males and females. • 19-5 • Describe the age-related changes that occur in the reproductive system. • 19-6 • Give examples of interactions between the reproductive system and each of the other organ systems. © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Basic Reproductive Structures (19-1) • Gonads • Testes in males • Ovaries in females • Ducts • Accessory glands • External genitalia © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Gametes (19-1) • Reproductive cells • Spermatozoa (or sperm) in males • Combine with secretions of accessory glands to form semen • Oocyte in females • An immature gamete • When fertilized by sperm becomes an ovum © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Checkpoint (19-1) 1. Define gamete. 2. List the basic components of the reproductive system. 3. Define gonads. © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. The Scrotum (19-2) • Location of primary male sex organs, the testes • Hang outside of pelvic cavity • Contains two chambers, the scrotal cavities • Wall • Dartos, a thin smooth muscle layer, wrinkles the scrotal surface • Cremaster muscle, a skeletal muscle, pulls testes closer to body to ensure proper temperature for sperm © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. -

N Wa Brahma/Atman

NÜ Wa God Brahma/Atman HUMANHUMAN EMBRYOLOGYEMBRYOLOGY Department of Histology and Embryology Jilin University ChapterChapter 11 IntroductionIntroduction toto HumanHuman EmbryologyEmbryology 1.1. WhatWhat isis EmbryologyEmbryology?? ontogenesis ovumovum Zygote/fertilizedZygote/fertilized ovumovum spermsperm NineNine monthsmonths (266(266 daysdays oror 3838 weeksweeks toto bebe exact)exact) inin thethe uterusuterus InfantInfant fetusfetus 1.1. WhatWhat isis EmbryologyEmbryology?? Traditional /descriptive embryology focuses on understanding the basic structural pattern of the embryonic body. Teratology is concerned with the reasons, mechanisms and protective measures of malformations. Comparative embryology seeks several general rules by comparison the identities or the differences among the development of many species. Experimental embryology researches on the causative factors in development by posing hypotheses and testing them with different experimental techniques. Chemical embryology researches on the changes of some chemical materials in cells or tissues and the chemical basis of morphogenesis during the development . Molecular embryology focuses on the molecular mechanisms of morphogenesis, and the gene regulation of embryonic development. Reproductive biology emphases on normal gametogenesis, endocrinology of reproduction, transport of gametes and fertilization, early embryonic development, and implantation of the mammalian embryo, in addition to more practically oriented problems involving techniques of fertilization and -

The Human Reproductive System

ANATOMY- PHYSIOLOGY-REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM - IN RESPONSE TO CONVID 19 APRIL 2, 2020 nd Dear students and parents, April 2 , 2020 Beginning two days prior to our last day at school I issued work packets to all students in all classed; the content of which was spanning a two-three week period. Now that our removal from school will continue to at least May 1st, I have provided the following work packets which will span the remainder of the year, should our crisis continue. The following folders are available: ANATOMY – PHYSIOLOGY 1. Packet – THE HUMAN REPRODUCATIVE AND ENDOCRINE SYSTEMS. 2. Packet- THE HUMAN NERVOUS SYSTEM 3. Packet handed our prior to our last day: THE HUMAN EXCRETORY SYSTEM ZOOLOGY 1. Packet- STUDY OF THE CRUSTACEANS 2. Packet- STUDY OF THE INSECTS 3. Packet- handed our prior to our last day- INTRODUCTION TO THE ARTRHROPODS- CLASSES MYRIAPODA AND ARACHNIDA AP BIOLOGY – as per the newly devised topics of study focus, structure of adapted test, test dates and supports provided as per the guidelines and policies of The College Board TO ALL STUDENTS! THESE PACKETS WILL BE GUIDED BY THE SAME PROCEDURES WE EMBRACED DURING FALL TECH WEEK WHERE YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR THE WORK IN THE PACKETS- DELIVERED UPON YOUR RETURN TO SCHOOL OR AS PER UNFORESEEN CHANGES WHICH COME OUR WAY. COLLABORATION IS ENCOURAGED- SO STAY IN TOUCH AND DIG IN! YOUR PACKETS WILL BE A NOTEBOOK GRADE. EVENTUALLY YOU SHALL TAKE AN INDIVIDUAL TEST OF EACH PACKET = AN EXAM GRADE! SCHOOL IS OFF SITE BUT NOT SHUT DOWN SO PLEASE DO THE BODY OF WORK ASSIGNED IN THE PACKETS PROVIDED. -

Evolution of the Two Sexes Under Internal Fertilization and Alternative Evolutionary Pathways

vol. 193, no. 5 the american naturalist may 2019 Evolution of the Two Sexes under Internal Fertilization and Alternative Evolutionary Pathways Jussi Lehtonen1,* and Geoff A. Parker2 1. School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, 2006 New South Wales, Australia; and Evolution and Ecology Research Centre, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052 New South Wales, Australia; 2. Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom Submitted September 8, 2018; Accepted November 30, 2018; Electronically published March 18, 2019 Online enhancements: supplemental material. abstract: ogy. It generates the two sexes, males and females, and sexual Transition from isogamy to anisogamy, hence males and fl females, leads to sexual selection, sexual conflict, sexual dimorphism, selection and sexual con ict develop from it (Darwin 1871; and sex roles. Gamete dynamics theory links biophysics of gamete Bateman 1948; Parker et al. 1972; Togashi and Cox 2011; limitation, gamete competition, and resource requirements for zygote Parker 2014; Lehtonen et al. 2016; Hanschen et al. 2018). survival and assumes broadcast spawning. It makes testable predic- The volvocine green algae are classically the group used to tions, but most comparative tests use volvocine algae, which feature study both the evolution of multicellularity (e.g., Kirk 2005; internal fertilization. We broaden this theory by comparing broadcast- Herron and Michod 2008) and transitions from isogamy to spawning predictions with two plausible internal-fertilization scenarios: gamete casting/brooding (one mating type retains gametes internally, anisogamy and oogamy (e.g., Knowlton 1974; Bell 1982; No- the other broadcasts them) and packet casting/brooding (one type re- zaki 1996; da Silva 2018; da Silva and Drysdale 2018; Han- tains gametes internally, the other broadcasts packets containing gametes, schen et al. -

Downloaded from Bioscientifica.Com at 10/06/2021 01:35:11PM Via Free Access 230

EFFECT OF BUSULPHAN ON THE DEVELOPING OVARY IN THE RAT B. N. HEMSWORTH and H. JACKSON Experimental Chemotherapy, Paterson Laboratories, Christie Hospital, Manchester 20 (Received 8th February 1963) Summary. Female rats were exposed to Busulphan on selected days between the 5th day of foetal life and Day 15 post partum, inclusive. The drug apparently had no effect on the foetal sex cells when admini- stered to the pregnant female between Days 5 and 7 post coitum. Later in pregnancy a destructive action became rapidly more powerful. So far as the developing ovary is concerned it would seem that the action of Busulphan at this dose level, i.e. 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally, is confined to the precursor of the oocyte, namely the oogonium and that when these cells enter meiotic prophase on about the 17th day of foetal life there is a marked decrease in their sensitivity to the action of the drug. The effect of the treatment on fertility has also been studied. INTRODUCTION The effect of Busulphan on the foetal ovary was described by Bollag (1954). He reported that a single dose given to pregnant rats 5 to 7 days ante partum resulted in sterility in the offspring. Later, Galton & Till (1956) stated that "earlier in pregnancy quite large doses do not interfere with its course and the F1 and F2 generations were apparently healthy". In view of these studies, it was decided to investigate the sensitivity of the proliferating cell systems of the gonad during development. A preliminary report of these investigations has been published elsewhere (Hemsworth & Jackson, 1962a).