ISSUE 1 2018 NORDISK ARKITEKTURFORSKNING Nordic Journal of Architectural Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trafikproblemer Ved Aalborg

Transportudvalget 2012-13 TRU alm. del Bilag 53 Offentligt Trafikproblemer ved Aalborg Og spillet om hvilke ”kasser”, der skal betale 3. Limfjordsforbindelse. Staten kan formentlig spare ca. 3 mia. kr. 1 Er Egholm-motorvejen en god ide -> 1. For Aalborg? 2. For Region Nordjylland 3. For staten 2 De seneste mange år er byudviklingen i Aalborg trukket mod øst. Og nu har vi et supersygehus på vej. 3 En ringvej endnu længere ude i øst end Limfjords- tunnelen virker umiddelbart mere anvendelig. 4 En anden løsning kunne være en bro midt imellem de nuværende. Det er en løsning, som jeg vil anbefale senere i min gennemgang. 5 Det virker til gengæld ulogisk, at en masse politikere i Nordjylland er så ivrige efter at lave en udbygning af vejnettet i vest. Det meget lavtliggende område i vest (1-2 m.) er næppe heller egnet til byudvikling. 6 Politikerne mener, at en Egholmforbin delse vil kunne fungere som en vestlig ringvej og reducere trafikken i centrum og ved City Syd. Men den vil medføre så store omveje, at effekten er tvivlsom. 7 Mod vest finder man en række populære bynære naturområder. De er præget af store vidder, påfaldende stilhed og flotte solnedgange. En guldgrube for Aalborg. Se fotoserie 8 Er Egholm-motorvejen en god ide 1. For Aalborg -> 2. For Region Nordjylland? 3. For staten 9 I den del af regionens vestlige del, der får ekstra fordele af en vestlig motorvej, bor kun 7 % af befolkningen. 10 I regionens østlige del bor hele 17 % af befolkningen, for hvem det er vigtigt, at øst-forbindelsen udbygges i takt med behovet! Det er ikke underordnet, hvad der vælges.11 E39 E45 Som det fremgår af dette kort, leder den påtænkte Egholm-motorvej til E39 i nord - ikke til E45! 12 Situation: Sydgående tunnelrør blokeres Egholm-motorvejen ender ved E39! Et uheld i tunnelen vil forhindre en ambulance fra E45 nord i at nå sygehuset. -

Budget 2019-2022

Budget 2019-2022 Bind I Indholdsfortegnelse Forord ..................................................................................................... 5 Ældre- og Handicapforvaltningen .................................... 115 Budget 2019-2022 i hovedtræk .............................................. 6 Fokusområder budget 2019-22 ............................................ 117 Hensigtserklæringer godkendt i budget 2019-2022 .. 8 Serviceydelser for ældre ........................................................... 119 Udgifter og indtægter i Aalborg Kommune ................... 17 Tilbud for mennesker med handicap................................... 123 Resultatopgørelse - Skattefinansieret område.......... 18 Myndighedsopgaver og administration .............................. 127 Finansiering ...................................................................................... 19 Tilskud og udligning .................................................................... 22 Skoleforvaltningen ................................................................... 129 Anlæg - skattefinansieret ........................................................ 28 Fokusområder budget 2019-22 ............................................ 130 Renter, afdrag og langfristet gæld ..................................... 29 Skoler ................................................................................................. 131 Balanceforskydninger ................................................................ 30 Administration .............................................................................. -

Sustainable Business Model for Socio-Economic and Environmental Protection with Reference to K Narayanapura, Bangalore, India - an Empirical Study

Sustainable Business Model for Socio-Economic and Environmental Protection with Reference to K Narayanapura, Bangalore, India - An Empirical Study Submitted By Surjit Singha Asst. Professor Dept of Commerce Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous) Shodh Pravartan Minor Research Project Centre for Research Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous) K Narayanapura, Kothanur Post, Bengaluru, Karnataka, 560077, India February 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I sincerely thank Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous) for providing an opportunity to conduct a Shodh Pravartan Minor Research Project I express my sincere gratitude to Rev. Dr Augustine George CMI, (Principal), Rev. Fr. Lijo P Thomas (Financial Administrator & Head Dept. of Computer Science), Rev. Fr. Som Zacharia (Director, Library & Information Technology & Director, Infrastructure Development), Rev. Fr. Emmanuel P.J. (Director, Kristu Jayanti College of Law, Director, International Relations, Faculty, Department of Psychology, Director, Jayantian Extension Services & Jayantian Alumni Association), Rev. Fr. Joshy Mathew (Faculty, Department of English), Rev. Fr. Deepu Parayil (Faculty, Department of Life Science), for their guidance and blessings. I thank Dr Aloysious Edward J, (Dean, Commerce and Management), Prof. Vijayakumar R (HoD, Department of Commerce) for their constant support and guidance. I also thank the Centre for Research, and all the Faculty coordinators for their constant inspiration and motivation to complete this project. I thank the management of Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous) for funding the entire project. I am grateful to St. Kuriaose Elias Chavara, and Almighty God for showering blessings upon me. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Surjit Singha is presently working as a faculty member in the Dept. of Commerce, Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous). Specialized in Commerce & Management, with an experience of more than 11+ years in Industry and Teaching and delivered more than 3,000 hours of Teaching lectures, he had published twelve articles in India and Bulgaria, and nine books in his credit. -

Aalborgus Byens Nye Livsnerve Derfor +BUS

Transport- og Bygningsudvalget 2015-16 TRU Alm.del Bilag 217 Offentligt +BAALBORGUS Byens nye livsnerve Derfor +BUS +BUS er et ambitiøst projekt, som skal løfte Aalborg. En nyanlagt moderne busbane giver byen en trafikal rygrad. Det vil skabe sammenhæng og udvikling. Samtidig løser +BUS konkrete udfordringer for byens trafik. Aalborg er en by, der vil frem. Stigende tilflytning og nye byggeprojekter og arbejdsplad- nye Universitetshospital, ungdomsboliger, private boliger og uddannelsesinstitutioner- ser betyder flere folk, der skal transporteres hurtigt og nemt rundt i byen. Med +BUS får nes mange udvidelser øger trafikpresset på infrastrukturen. Der er behov for en løsning, vores kollektive trafik et effektivt løft - til glæde for både pendlere, bilister og indbygge- som både udvikler og understøtter byens vækst. re. Samtidig baner den vejen for endnu mere byudvikling. En strømlinet kollektiv trafik gør nemlig vores by endnu mere attraktiv for nye indbyggere og virksomheder. +BUS skal gøre byen mere tilgængelig for både brugere af offentlig trafik og biltrafikan- ter. Med høj kapacitet, stabilitet og stor komfort vil +BUS gøre det hurtigere og mere Aalborg står overfor en række trafikale udfordringer. Der er allerede pres på både kol- attraktivt at bevæge sig gennem byens vækstakse. Når flere bruger +BUS, er der også lektiv- og biltrafik. Samtidig udvikler byen sig i et konstant tempo. Nybyggerier som det bedre plads til bilerne på vejene. 60 biler = 1 +BUS Aalborg i vækst Der bygges for milliader i Aalborg. Fx står Aalborg for 2/3 af alle nybyggede ungdomsboligerVESTBYEN i hele Danmark. Væksten er isærØSTBYEN koncentreret i samme rute 1 gennem byen, som +BUS skal følge. -

Østbyen BRT Og Byudvikling I Østbyen

Østbyen BRT og byudvikling i Østbyen Illustration: Friis & Moltke Vestbyen Midtbyen Østbyen Universitetetsområdet Jomfru Ane Gade Selma Lagerløfs Vej Nytorv Karolinelund Servicebyen Vestbyen Station (Boulevarden) Politigården Eternitten Campus Forum Nyt Aalborg Haraldslund Universitetshospital Vestre Fjordvej John F. Kennedys Plads Sohngårdsholmsparken Universitetet Danalien Gigantium Væddeløbsbanen Pontoppidanstræde BRT kommer til at bevæge sig gennem Aalborg på den 12 Scoresbysundvej Grønlands Torv km lange strækning fra Væddeløbsbanen gennem midtbyen til Nyt Aalborg Universitetshospital. Pendlerpladsen Om BRT BRT er en miljøvenlig højklasset busforbindelse, der giver kortere rejsetid og skaber større sammenhæng mellem transport og byudvikling. BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) BRT er kendetegnet ved: er en letbane på gummihjul • Kørsel i egen busbane. • Prioritering i lyskryds. • Jævn overflade uden huller og bump. • Hurtig og niveaufri ind- og udstigning. • Komfortable og støjsvage køretøjer med plads til 150-200 passagerer. Trafikændringer i Østbyen Servicebyen Bornholmsgade Selma Lagerløfs Vej Karolinelund I Bornholmsgade opretholdes trafikken næsten som i dag, men der etableres et nyt lyskryds ved Sjællandsgade, så fodgængere kan kryd- se vejen sikkert. Eternitten Sohngårdsholmsvej Frederik Bajers Vej Humlebakken På Sohngårdsholmsvej etableres busbane i midten af vejen. Det betyder, at man ikke kan svinge til venstre fra Sohngårdsholmsvej ind ad sidevejene. Når busbanen erUniversitetet etableret, skal man derfor altid Danalien køre højre ind og højre ud af sidevejene til Sohngårdsholmsvej. En del sideveje lukkes, og der etableresPontoppidanstræde nye lyskryds ved Magisterparken og Kollegievej. Gigantium Scoresbysundvej Anlægsarbejdet PendlerpladsenNår anlægsarbejdet begynder i 2019, arbejdes der på forskellige dele Grønlands Torv af den 12 km lange BRT strækning, så den øvrige trafik kan afvikles så problemfrit som muligt i alle dele af byen. -

The Educational City of Aalborg

THE EDUCATIONAL CITY OF AALBORG Table of Content Nordkraft ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Musikkens Hus ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Karolinelund ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Aalborg Cable Park .................................................................................................................................... 3 Vestre Fjordpark .......................................................................................................................................... 3 GAME Streetmekka Aalborg ..................................................................................................................... 4 Central library ............................................................................................................................................. 4 CREATE ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Utzon Center ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aalborghus Castle ..................................................................................................................................... -

Lokalplan 1-1-124

Jammerbugten Pandrup Dronninglund Storskov Tylstrup Aabybro Sulsted Hjallerup Dronninglund Grindsted Hammer Bakker Uggerhalne Vestbjerg Vadum Vodskov Langholt Brovst Stae Ulsted Vester Hassing Egholm NØRRESUNDBY Hou Rørdal Gandrup Øster Uttrup Hasseris AALBORG Limfjorden Nørholm Nørre Tranders Koldkær Klitgård Sønder Tranders Klarup Bisnap Skalborg Gug Stavn Storvorde Sønderholm Hals Frejlev Gistrup Visse Dall Villaby Skelby Farstrup Sejlflod Kølby Barmer Nibe Skellet Lillevorde Valsted Svenstrup Nøvling Egense Gudumholm Mou Godthåb Sebbersund Aalborg Bugt Ferslev Store Gudum Ajstrup Bislev Vaarst Gudumlund Ellidshøj Fjellerad Nørre Kongerslev Volsted Dokkedal Støvring Kongerslev Skørping Lille Vildmose Terndrup Aars Øster Hurup Rold Skov Maj 2016 LOKALPLAN 1-1-124 MED MILJØRAPPORT (MV) Park og børnehave, Karolinelund Aalborg Midtby Vejledning Lokalplan 1-1-124 Park og børnehave, Karolinelund, Aalborg Midtby Hvad er en lokalplan? Lokalplaner skal styre den fremtidige udvikling i et område og give borgerne og byrådet mulighed for at vurdere konkrete tiltag i sammenhæng med planlægningen som helhed. I en lokalplan fastlægger byrådet bestemmelser for, hvordan arealer, nye bygninger, beplantning, veje, stier osv. skal placeres og udformes inden for et bestemt område. Hvad består lokalplanen af? Redegørelsen, hvor baggrunden og formålet med lokalplanen beskrives, og der fortælles om lokalplanens indhold. Her redegøres der bl.a. også for de miljømæssige forhold, om hvordan lokalplanen forholder sig til anden planlægning, og om gennemførelse af lokalplanen kræver tilladelser eller dispensationer fra andre myndigheder. Planbestemmelserne, der er de bindende bestemmelser for områdets fremtidige anvendelse. Illustra- tioner samt tekst skrevet i kursiv har til formål at forklare og illustrere planbestemmelserne og er således ikke direkte bindende. Bilag: Matrikelkort, der viser afgrænsningen af området i forhold til skel. -

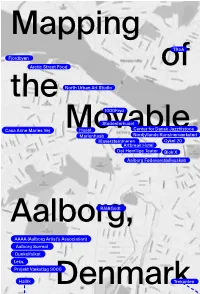

Mapping of the Movable Aalborg, Denmark

Mapping TRoA Fjordbyen Arctic Street Food of the North Urban Art Studio 1000Fryd Studenterhuset Casa Anne Maries Vej MovableHuset Center for Dansk Jazzhistorie Marienhaab Nordjyllands Kunstnerværksted Klaverstemmeren Cykel 20 Artbreak Hotel Det Hem’lige Teater Blok X Aalborg Fødevarefællesskab Aalborg,Råt&Godt AAAA (Aalborg Artist’s Association) Aalborg Surreal Dunkelfolket f.eks. Projekt Vækstlag 9000 Hal9k DenmarkTrekanten Mapping of the Movable is a digital guide that locates and gives a voice to self-organized spaces, subcultures, and commons within the city of Aalborg. It introduces twenty-eight existing groups that are activating the city in different ways through urban actions, activities, social gatherings, the arts, crafts, or activism. The guide is centered on conversations with the different communities about their everyday rhythms, Introduction social aspects, self-organized structures, decision-making processes, and challenges or (un)fulfilled dreams. The conversations also highlight the complex networks they continually reproduce as part of their dynamic relationship to the city. This is relevant since Aalborg is undergoing a post-industrial transformation into a knowledge and cul- tural city, similar to many others across the globe. Mapping of the Movable, Aalborg, Denmark, 2021 This project is conceived by artist Maj Horn together with the contemporary art initiative f.eks. based in Aalborg. Mapping Artistic Practice of the Movable is a multi-layered artistic investigation that and Project Development: Maj Horn has taken shape over several years through performative interactions, public workshops, city walks, conversations, Curation, Event organization, and digital gatherings. The communities that are a part of and Facilitation: f.eks. / Scott William Raby this guide have been selected through an organic flow of interactions, where project participants have suggested the Local research and collaboration: Kamilla Mez, Casper Clasen featured organizations. -

The Nordic Cities

NORDIC CITIES IN TRANSITION 450 Nordic Competition I urban projects I & quality of life The Nordic Democratic I welfare model in I urban spaces transition Ideas & strategies Innovation and I I inclusion New urban I communities his is a discussion paper about the current status of Nordic urban development.T It is based on an analysis of 450 selected urban projects from 18 Nordic cities – all members of the Nordic City Network. The discussion paper is produced by Gehl Architects for Nordic City Network. Editor & Text Louise Vogel Kielgast, Project Manager, Gehl Architects Layout & Graphics Pernille Juul Schmidt, Designer, Gehl Architects Steering Committee Per Riisom, Director, Nordic City Network Christer Larsson, Chairman Nordic City Network & Stadsbygningsdirektør Malmö Stad Henrik Poulsen, Seniorkonsulent, Odense Kommune Editorial Team Ewa Westermark, Partner, Gehl Architects Tom Nielsen, Professor School of Architecture, Aarhus & Urban specialist, Gehl Architects Photography Cover photo collage / Bottom left: Fredericia — Grow your city, credit: Fotoco Top left: Photo from Nordiska Museets Arkiv, credit: Eric Liljeroth Right: Boy doing handstand in Rosengård, credit: Anders Hansson Bottom right: Illustration of Youth residences in Aalborg, credit: Henning Larsen Architects Background: Tromsø aerial photo, credit: Paul:74 (Flickr) Page 27 / Kulturväven, credit: Fredrik Larsson Pages 7 & 38 / Photos from Fredericia - Grow your city, credit: Fotoco Page 42 / ‘De fem haver’, credit: Grontmij, IN TRANSITION IN Sønderborg Forsyning, Sønderborg -

PERFORMATIV Brug Af Det Offentlige RUM

PERFORMATIV brug af det offentlige RUM Bachelorprojekt i Performance Design Maj 2016 (25FilmsBerlin, 2012) Lærke Pedersen & Normen Göran Dommann Vejleder: Anja Mølle Lindelof HumBach Gruppe 6 - Hus 7.1 Studienr. 51496 // 52204 Antal anslag: 71.247 Lærke Pedersen & Normen Döran Dommann PERFORMATIV brug af det offentlige RUM ○ Maj 2016 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract This papers purpose is to outline some of the essential features of performance theory the design-thinking approach, as promoted by Tim Brown, CEO of the American design- and innovation company IDEO, and a Nordic approach to audience development, formulated by assistant lector of communications and humanities at Roskilde University, Anja Mølle Lindelof. Focused around case-examples from Aalborg, Copenhagen and Berlin, and traditional and modern cultural institutions, the paper attempts to reveal critical mismatches in institutional communication on a processual level. The paper furthermore suggest to implement the »creative-placemaking«-approach, by Ann Markusen and Anna Gadwa, into city-development and institutional processes to secure a sustainable and democratic design of the city-park Karolinelund, which is located in the municipal of Aalborg. The paper concludes that it is potentially profitable for cultural institutions and municipals to implement a human-centered and design-based approach to nourish institutional innovation. 1 Lærke Pedersen & Normen Döran Dommann PERFORMATIV brug -

Aalborg Universitet Projektkatalog for Byggeri & Anlæg P1-Projekter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by VBN Aalborg Universitet Projektkatalog for byggeri & anlæg P1-projekter Pedersen, Lars Publication date: 2009 Document Version Også kaldet Forlagets PDF Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Pedersen, L. (red.) (2009). Projektkatalog for byggeri & anlæg: P1-projekter. Department of Civil Engineering, Aalborg University. DCE Latest News Nr. 10 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: December 26, 2020 Basisåret 2009-10 Projektkatalog for byggeri & anlæg Redigeret af Lars Pedersen ISSN 1901-7308 DCE Latest News No. 10 Institut for Byggeri og Anlæg Aalborg Universitet Institut for Byggeri og Anlæg Ved Det Ingeniør-, Natur- og Sundhedsvidenskabelige Faktultet DCE Latest News No. 10 Projektkatalog for byggeri & anlæg P1-projekter Redigeret af Lars Pedersen Okt 2009 © Aalborg Universitet Udgivet 2009 af Aalborg Universitet Institut for Byggeri og Anlæg Sohngårdsholmsvej 57, DK-9000 Aalborg, Danmark Trykt i Aalborg på Aalborg Universitet ISSN 1901-7308 DCE Latest News No. -

Program Politisk Forum 2016

KONFERENCE TEKNIK & MILJØ ’16 PROGRAM / 14.–15. april 2016 Aalborg Kongres & Kultur Center TEKNIK & MILJØ ’16 KOMMUNALPOLITISK KONFERENCE KOMMUNALPOLITISK BYEN, LANDET OG VANDET Konference 2 TEKNIK & MILJØ ’16 PLAN OVER AALBORG KONGRES & KULTUR CENTER STUEN 1. SAL Det lille teater Aalborghallen Foyer Plenum Radiosalen Musiksalen Gæste- Standeområde salen Til stuen KL-Lounge Laugs- stuen Latiner- Bonde- Kræm- stuen stuen mer- Sekretariat stuen Til 1.sal Forhal Indgang Konference TEKNIK & MILJØ ’16 3 VELKOMMEN TIL TEKNIK & MILJØ ’16 Byen, landet og vandet. Det er Danmark. Og det er det Danmark, vi Landet er under et andet pres. Mange års statslig detailstyring af forvalter og holder af. Politikere for teknik og miljø deler passionen kommuneplanlægningen har medført, at planloven skal revideres. om at bevare og forny det fysiske Danmark. Svaret er ikke deregulering – men mere fleksible statslige rammer, så den lokale planlægning igen kan skabe synergi og vækst. Teknik og Miljø er i sig selv en kommunal velfærdsydelse. Samtidig er teknik og miljø rammerne for de andre kommunale velfærds- Vandmiljøet skal både beskyttes – og benyttes til kvælstofudled- ydelser. Vi bygger til leg og læring i institutioner og skoler. Vi skaber ning. Det kan let blive en konflikt. Her har kommunale vandråd og byrum for de skæve og de sjove. Vi sørger for husrum til de gamle vådområder vist sig som en succes. Nu mangler vi bare, at staten og flygtningene. giver bedre mulighed for at vådområderne kan benyttes til klimatil- pasning. Det giver helt unikke udfordringer og muligheder. Mange gange må vi vælge og prioritere, men ofte har vi også med politisk timing mu- Byen, landet, vandet – og menneskerne.