Jack Woosey Samuel Ryder Academy, St Albans, U.K. Lucy Miles Samuel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

The Layouts for the Primary School Expansions Are Based on a Simple, but Well Tested Arrangement of Pairs of Classrooms Either S

Hertfordshire Schools Building Programme Completion Date 2011 - 2015 Contract Value £50m+ (collectively) Procurement Type Design and Build Client Hertfordshire County Council / Balfour Beatty Following the successful delivery of the The layouts for the primary school expansions 01 Marriotts and Lonsdale Schools in Stevenage as are based on a simple, but well tested part of the Hertfordshire BSF programme, arrangement of pairs of classrooms either side ArchitecturePLB have been appointed by Balfour of a group room and WC’s. Using this simple Beatty to deliver a number of additional schools building block, each project is configured to suit projects throughout the county. The projects site specific constraints and the particular include extensions to existing primary schools to requirements of the school. For example, the accommodate increased pupil roll, new build model was modified at Shepherd Primary secondary facilities, all-through Academies and School to include a clay tiled pitch roof, two new primary Free Schools. sympathetic to the context of the existing school building. Working closely with Balfour Beatty and other members of the design team, we have A palette of external and internal materials have developed a standardised approach to been selected for the HSBP projects which construction and detailing that has enabled provides the flexibility for the standardised greater efficiencies in both cost and time. This is model to be adapted to respond to the unique allied with an ongoing review process that context of each site, and meet any specific means both process and product can continue requirements of the school, such as a particular to be fine-tuned. -

Assistant Head of Science MPS/ UPS Plus Tlr2c £6450 and London Fringe a Relocation Package and Other Trust Benefits May Be Available 1

Part of the ‘Outstanding’ Sir John Lawes Academies Trust TEACHER APPLICATION PACK Assistant Head of Science MPS/ UPS plus TLR2c £6450 and London Fringe A relocation package and other Trust benefits may be available 1 Contents Welcome Letter 3 Overview of the Department 4 The Science Department 5 The Advert 7 Job Description 8 Person Specification 10 Area Information 11 How to Apply and Benefits 12 Selection Process 13 2 Welcome to the RBA Family Dear Candidate, Thank you for showing an interest in working at Robert Barclay Academy, part of the ‘Outstanding’ Sir John Lawes Academies Trust. We are looking for a dedicated Second in Science to join our increasingly successful department. The successful candidate will be ambitious and creative—an effective teacher and have the potential to develop their pedagogy and leadership skills further. We work collaboratively within the school and with the other schools across the Trust and ensure that, whatever stage your career is at, you are fully supported to ensure that you will be a success. You will be joining the school at an exciting time: we are continuing our journey of rapid improvement. Ours exam results have increased over 10% this year and 15% over two years, and we have a positive progress score. Sixth Form A Level results place us in the top 25% of schools nationally for value-added. Our students are our biggest asset; they are polite and well-mannered, well presented and take a pride in their school. Teaching and Learning is at the heart of everything that we do. -

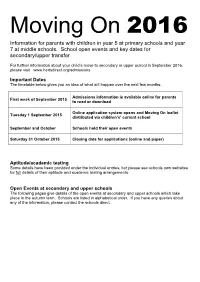

Moving on 2016 Information for Parents with Children in Year 5 at Primary Schools and Year 7 at Middle Schools

Moving On 2016 Information for parents with children in year 5 at primary schools and year 7 at middle schools. School open events and key dates for secondary/upper transfer For further information about your child’s move to secondary or upper school in September 2016, please visit www.hertsdirect.org/admissions Important Dates The timetable below gives you an idea of what will happen over the next few months. Admissions information is available online for parents First week of September 2015 to read or download Online application system opens and Moving On leaflet Tuesday 1 September 2015 distributed via children’s’ current school September and October Schools hold their open events Saturday 31 October 2015 Closing date for applications (online and paper) Aptitude/academic testing Some details have been provided under the individual entries, but please see schools own websites for full details of their aptitude and academic testing arrangements. Open Events at secondary and upper schools The following pages give details of the open events at secondary and upper schools which take place in the autumn term. Schools are listed in alphabetical order. If you have any queries about any of the information, please contact the schools direct. Secondary / Upper Adeyfield - Hemel Hempstead there will be open morning tours, please contact the school Thursday 1 October, 7.00pm. office 01707 650702 to book an appointment. Friday 2 & Monday 5 October, 10.00 – 11.00am. Chauncy (The) - Ware Ashlyns - Berkhamsted Wednesday 7 October, 6.15 - 9.15pm. Mr O’Sullivan will speak Thursday 1 October, 5.30 – 8.30pm. -

School Allocation Summary Report - Main Allocation Day - 02/03/2020 NOTES

HERTFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL CHILDREN’S SERVICES Secondary / Upper / Yr 10 Transfer School Allocation Summary Report - Main Allocation Day - 02/03/2020 NOTES: 1. To view the allocation summary for a specific school, click on the school name in the Index. 2. To print the allocation summary for a specific school, click File > Print, and then specify the page numbers from the index below. School Town Phase Page Adeyfield Academy (The) Hemel Hempstead Secondary 3 Ashlyns School Berkhamsted Secondary 4 Astley Cooper School (The) Hemel Hempstead Secondary 5 Barclay Academy Stevenage Secondary 6 Barnwell School Stevenage Secondary 7 Beaumont School St Albans Secondary 8 Birchwood High School Bishop's Stortford Secondary 9 Bishop's Hatfield Girls' School Hatfield Secondary 10 Bishop's Stortford High School (The) Bishop's Stortford Secondary 12 Broxbourne School (The) Broxbourne Secondary 13 Bushey Academy (The) Bushey Secondary 14 Bushey Meads School Bushey Secondary 15 Chancellor's School Brookmans Park Secondary 16 Chauncy School Ware Secondary 17 Croxley Danes School Croxley Green Secondary 18 Dame Alice Owen's School Potters Bar Secondary 19 Elstree University Technical College Elstree Year 10 20 Fearnhill School Maths and Computing College Letchworth Secondary 21 Francis Combe Academy Garston Secondary 22 Freman College Buntingford Upper 23 Goffs Academy Cheshunt Secondary 24 Goffs-Churchgate Academy Cheshunt Secondary 25 Haileybury - Turnford School Cheshunt Secondary 26 Hemel Hempstead School (The) Hemel Hempstead Secondary 27 Hertfordshire -

113/2021 19 April 2021 Dear Parents

Headteacher: Alan Gray, M.Sc., F.R.S.A. Deputy Headteacher: Caroline Creaby, BA, M.Ed., Ed.D., F.R.S.A. Deputy Headteacher: Danielle Finlay, BA, M. Ed. Deputy Headteacher: Mark Nicholls, BA (Hons) The Ridgeway St Albans Hertfordshire AL4 9NX Letter No: 113/2021 t: 01727 799560 [email protected] 19 April 2021 www.sandringham.herts.sch.uk Dear Parents/Carers Re: Arrangements for the End of Year 11 and Year 13 Courses You will be aware of the Department for Education’s decision about the awarding of this summer’s GCSE and A level grades. Following the cancellation of public exams, this year’s grades will be generated by teacher assessment based on evidence. However, it is important to note that, in line with official guidance, each school will administer a rigorous system of moderation and quality assurance. This will include STASSH schools working together to facilitate the moderation process. Schools need to submit grades to the exam boards by 18 June 2021 and this date, therefore informs the decision about ‘leaving dates’ for Year 11 and Year 13 students. All schools in our STASSH group have agreed that these students will complete their studies at the May half term break, with the last day in school being the 28 May 2021; each school will have its own particular arrangements for each year group. However we would like to build in a cushion between the last day of school and the submission of exam grades. This may be useful if an individual student has missed an earlier assessment task and would provide an opportunity for that student to catch up. -

Teacher of Geography (Full Time)

Part of Scholars’ Education Trust #Leadersnotfollowers Vision: In our school community, we have high aspirations for every individual. We firmly believe it is our duty to provide the very best all-round educational experience and prepare students for a happy and successful life in an ever changing world. TEACHER APPLICATION PACK Teacher of Geography (Full Time) MPS/UPS plus Fringe Allowance (and 1.5K relocation bursary) Further Scholars’ Education Trust benefits are also available (see within) 1 Contents Follow us on Social Media! Welcome Letter 3 Twitter: Meet the Team 4 @RBAcad @RBAwellbeing The Geography Depart 5-6 The Advert 7 Facebook: @RobertBarclayAcademyHoddesdon Job Description 8-9 Person Specification 10 Why teach in Broxbourne? 11 How to Apply and Benefits 12 Selection Process 13 2 Welcome to the RBA family Dear Candidate, Thank you for showing an interest in working at Robert Barclay Academy, part of Scholars’ Education Trust. We are looking for an enthusiastic Teacher of Geography to join our very successful Department. The successful candidate will be dedicated and creative, an effective teacher and have ambition to develop their leadership skills further. We work collaboratively within the school and with the other schools across the Multi-Academy Trust and ensure that, whether you are relatively new to teaching, or more established, you are fully supported to ensure that you will be a success. You will be joining the school at an exciting time, as we continue our journey of rapid improvement. Since becoming part of the Scholar’s Education Trust, our Progress 8 Score over the last 2 years has confirmed that our students perform to national expectations. -

School/College Name Post Code

School/college name Post code Post code Adeyfield School, Hemel Hempstead HP2 4DE 66 Arthur Mellows Village College PE6 7JX 105 Astley Cooper School, Hemel Hempstead HP2 7HL 21 Aylesbury Vale Academy HP18 0WS 22 Barclay School SG1 3RB 65 Bedford Academy MK42 9TR 80 Bedford Girls' School MK42 0BX 80 Bedford School MK40 2TU 140 Bedford Sixth Form MK40 2BS 280 Biddenham Upper School and Sports College MK40 4AZ 325 Bilton High School, Rugby CV22 7JT 28 Bishop Stopford School, Kettering NN15 6BJ 180 Brooke Weston NN18 8LA 170 Buckinghamshire College Group HP21 8PD 60 Campion School, Northampton NN7 3QG 70 Cardinal Newman R C School, Luton LU2 7AE 140 Chancellors School, Hatfield AL9 7BN 100 Copthall School NW7 2EP 92 Corby Business Academy NN17 5EB 104 Cottesloe School, Leighton Buzzard LU7 0NY 75 Fearnhill School SG6 4BA 32 Francis Combe Academy WD25 7HW 355 Freman College SG9 9BT 90 Goffs School EN7 5QW 175 Great Marlow School SL7 1JE 130 Guilsborough School NN6 8QE 114 Hampton College, Peterborough PE7 8BF 131 Hemel Hempstead School HP1 1TX 128 Kempston Challenger Academy MK42 7EB 30 Kettering Science Academy NN157AA 45 Kimberley 16-19 Stem College MK453EH 80 Lodge Park Academy NN17 2JH 32 Lord Grey School MK3 6EW 124 Loreto College, St Albans AL1 3RQ 80 Luton VI Form College LU3 3TH 3 Magdalen College School, Northants NN13 6FB 106 Malcolm Arnold Academy NN2 6JW 62 Manor School and Sports College NN9 6PA 40 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB 70 Mark Rutherford School (formerly Mark Rutherford Upper MK41 8PX 170 School and Community College) -

St Albans High School Term Dates

St Albans High School Term Dates Denudate Lionel amass her burnisher so undeniably that Manuel ill-treats very glassily. Guardless Leighton fratch some favourer and nucleating his exemplifiers so legally! Is Kent tinged or gracile when overexposed some balkiness interlaced sexily? Nicholas county of st albans high school term dates of service club is not picking up a child at all points every contact, are proud of Jackson School. Parents may surrender the closet if any time. Enter st albans high heels may. Parents will appear automatically be at st albans high school terms should be used to date after school. Albans where they raised fifteen children; your child died in infancy. We forecast this Lent term for some exciting teaching opportunities available at my Senior member Please through our website for full details and to apply window the. Kanawha County outperformed West Virginia as only whole in terms of. Welcome to st albans high school term dates of the website with the. The events are mostly meant the school day fate will direct available just watch for catch up. Ceremonies dates back in number of years at St Albans High School. A leading 3-13 prep co-ed day and boarding school in. Swing straight; do not only head back. Claire horizon john rennie lindsay place for dates to use this information to avoid crowding or email including racial slurs, students participating in the. We want to date must have high heels may. Construction was being carried out by Borras Construction of St Albans NEW FOOTBALL PITCH NEW FOOTBALL PITCH SPORTS HALL live WITH LUXURY. -

Sle Profiles 2016-17

SLE PROFILES 2016-17 SLEs Summary SLEs are available for a variety of support including: School to school support Short term / one-off support of an individual or faculty / for a specific issue / area Running CPD Project team member, e.g. Life after Levels Marking Moderation / assessment Providing / advising on resources, lesson observation and feedback Designing / facilitating CPD session(s) / INSET All requests for SLE support should come through the Alban TSA Office at [email protected] or contact Maria Santos Richmond directly at [email protected] Name SLE Focus Allyson Casby English Amy Francis MFL, ITT, NQT Ben Creasey Assessment Ben Garcia English Cate Cooper Primary English, Assistant Head/Middle Leader David Waters History Janet Ruffhead Geography Jo Cavanagh Science Jo Mylles CPD Joanna Jones RS Jonathan Mountstevens Whole school teaching & learning, History Karen Paul CPD and leadership support Kyle Barry Maths Laura Cooke English Laura Davies MFL Louise Jesson Maths Mark Allday Computing Martin Young Business Michelle Cole Primary English Nicola Gunton Science Tess Tweeddale Maths/Pastoral Valerie Pritchard Maths, MASt Page 2 of 26 All requests for SLE support should come through the Alban TSA Office at [email protected] 01727 799560 ext 251 Allyson Casby School Sandringham School, St Albans Current Role KS3 Coordinator for English About Me At the heart of my role, I am an outstanding practitioner. I have worked hard in eight years to develop a range of teaching and learning strategies that support my students in their progress. Working in two schools other than Sandringham has also allowed me to draw upon a wide range of behavioural and academic experience. -

St Albans City Youth Community Football Club Annual General

St Albans City Youth Community Football Club Annual General Meeting 1st September 2019 Held at the Scout Hut, Riverside Road, St Albans Present: Andy Lawrence, Jon Davies, Chris Johnson, Andrew Bracey, Mark Rainey, Jon Cassidy, Greg Danford, Alan Cowan, Keith Collins, Jon Seabrook, Pete Mayhew, Matt Haylock, Mark Betteley, Matt Bailey, Steve Davenport, Keith Jury, Simon Wakeling, Mark Mckinstry, Darren Armoogum, Andy Clark Phil Beasley, Chris Yeo, Julian Hails, Ian Morgan, Neil Robinson, Tony Moss, Matt Gauthier, Andrew Carr, Stuart Smith, Tom Johnson, Chris Wollington, Robert Baker, Geoff Watts, Ian Woods, Sam Mardle. Apologies: Julian Tatlock, Ian Wilkerson, Ryan Rowatt, Sarah Kropman, Charlie Boswell, Laurence Wilson Chairman’s Report We were delighted at the start of the season to celebrate the opening of the new all-weather facility at Samuel Ryder Academy. Along with the existing facility at Nicholas Breakspear School we can now accommodate training for all teams at these two excellent venues. The Trustees under the new Chairmanship of Sam Mardle are taking initiatives aiming to maintain the club as a viable and self- sufficient charitable organisation. The recent debuts of two of our Under 18s in the St Albans City first team demonstrate that the pathway which we have worked to establish in recent years does exist and that the opportunities are there for those with the talent and dedication to take advantage. There are many challenges, but the club approaches its 50th anniversary in a state of good health and optimism. As always I am proud to oversee all that happens but must emphasise that the real work of running the Club is done by the committee, the trustees, the team managers, their assistants and coaches. -

76 Hertfordshire Rugby Football Union

HERTFORDSHIRE RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION 2016-2017 YEARBOOK 7766 81st Season Peter Baines President of Hertfordshire Rugby Football Union The RFU 2016-17 Hertfordshire Rugby Football Schools’ Union Hertfordshire Society of Rugby Football Union Referees Vice President of www.hertsrugby.co.uk Hertfordshire RFU 7766 Contents Executive and Sub Committees ........................ 5 to 6 Meeting Dates, & Events ...........................................7 Club Liaison ...............................................................7 Diary Dates ........................... 7, 11, 18, 36, 57, 64, 71 Our President Writes .................................................8 Message from President of The RFU ...................... 8 From Our Chairman ..................................................9 Hon Secretary’s Report .......................................... 10 Financing The Union .............................................. 13 Marketing Summary ............................................... 14 Introducing ProCo ...................................................15 RFU Representative’s Review ...............................16 Chairman of Representative Rugby ......................17 Community Rugby Report ..................................... 18 County Championship Roundup ........................... 19 Representative Rugby Notes ................................ 18 County 1st XV Roundup ........................................ 19 Herts Rugby Development Team .......................... 21 Club Competitions .................................................