Perimeter Rules, Proprietary Powers, and the Airline Deregulation Act: a Tale of Two Cities...And Two Airports Robert B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Overview and Trends

9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 15 1 M Overview and Trends The Transportation Research Board (TRB) study committee that pro- duced Winds of Change held its final meeting in the spring of 1991. The committee had reviewed the general experience of the U.S. airline in- dustry during the more than a dozen years since legislation ended gov- ernment economic regulation of entry, pricing, and ticket distribution in the domestic market.1 The committee examined issues ranging from passenger fares and service in small communities to aviation safety and the federal government’s performance in accommodating the escalating demands on air traffic control. At the time, it was still being debated whether airline deregulation was favorable to consumers. Once viewed as contrary to the public interest,2 the vigorous airline competition 1 The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 was preceded by market-oriented administra- tive reforms adopted by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) beginning in 1975. 2 Congress adopted the public utility form of regulation for the airline industry when it created CAB, partly out of concern that the small scale of the industry and number of willing entrants would lead to excessive competition and capacity, ultimately having neg- ative effects on service and perhaps leading to monopolies and having adverse effects on consumers in the end (Levine 1965; Meyer et al. 1959). 15 9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 16 16 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY spurred by deregulation now is commonly credited with generating large and lasting public benefits. -

Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999

9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 171 Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999 UNFAIR PRICING AND CAPACITY RESPONSES 1. Date Raised: May 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Northwest Airlines Description: AccessAir, a new airline headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa, began service in the New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles to Mo- line/Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois, markets. Northwest offers connecting service in these markets. AccessAir alleged that Northwest was offering fares in these markets that were substantially below Northwest’s costs. 171 9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 172 172 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY 2. Date Raised: March 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Delta, Northwest, and TWA Description: AccessAir was a new entrant air carrier, headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa. In February 1999, AccessAir began service to New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles from Des Moines, Iowa, and Moline/ Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois. AccessAir offered direct service (nonstop or single-plane) between these points, while competitors generally offered connecting service. In the Des Moines/Moline–Los Angeles market, Ac- cessAir offered an introductory roundtrip fare of $198 during the first month of operation and then planned to raise the fare to $298 after March 5, 1999. AccessAir pointed out that its lowest fare of $298 was substantially below the major airlines’ normal 14- to 21-day advance pur- chase fares of $380 to $480 per roundtrip and was less than half of the major airlines’ normal 7-day advance purchase fare of $680. -

A Free Bird Sings the Song of the Caged: Southwest Airlines' Fight to Repeal the Wright Amendment John Grantham

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 72 | Issue 2 Article 10 2007 A Free Bird Sings the Song of the Caged: Southwest Airlines' Fight to Repeal the Wright Amendment John Grantham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation John Grantham, A Free Bird Sings the Song of the Caged: Southwest Airlines' Fight to Repeal the Wright Amendment, 72 J. Air L. & Com. 429 (2007) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol72/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. A FREE BIRD SINGS THE SONG OF THE CAGED: SOUTHWEST AIRLINES' FIGHT TO REPEAL THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT JOHN GRANTHAM* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 430 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .................... 432 A. THE BATTLE TO ESTABLISH AIRPORTS IN NORTH T EXAS .......................................... 433 B. PLANNING FOR THE SUCCESS OF THE NEW AIRPORT ........................................ 436 C. THE UNEXPECTED BATTLE FOR AIRPORT CONSOLIDATION ................................... 438 III. THE EXCEPTION TO DEREGULATION ......... 440 A. THE DEREGULATION OF AIRLINE TRAVEL ......... 440 B. DEFINING THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT RESTRICTIONS ................................... 444 C. EXPANDING THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT ........... 447 D. SOUTHWEST COMES OUT AGAINST THE LoVE FIELD RESTRICTIONS ............................... 452 E. THE END OF AN ERA OR THE START OF SOMETHING NEW .................................. 453 IV. THE WRIGHT POLICY ............................ 455 A. COMMERCE CLAUSE ................................. 456 B. THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT WILL REMAIN STRONG LAW IF ALLOWED .................................. 456 1. ConstitutionalIssues ......................... 456 2. Deference to Administrative Agency Interpretation............................... -

American Airlines' Actions Raise Predatory Pricing Concerns

American Airlines’ Actions Raise Predatory Pricing Concerns Michael Baye and Patrick Scholten prepared this case to serve as the basis for classroom discussion rather than to represent economic or legal fact. The case is a condensed and slightly modified version of the public copy documents involving case No. 99-1180-JTM initially filed on May 13, 1999 in United States of America v. AMR Corporation, American Airlines, Inc., and AMR Eagle Holding Corporation. INTRODUCTION1 Between 1995 and 1997 American Airlines competed against several low-cost carriers (LCC) on various airline routes centered on the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport. During this period, these low- cost carriers created a new market dynamic charging markedly lower fares on certain routes. For a certain period (of differing length in each market) consumers of air travel on these routes enjoyed lower prices. The number of passengers also substantially increased. American responded to the low cost carriers by reducing some of its own fares, and increasing the number of flights serving the routes. In each instance, the low-cost carrier failed to establish itself as a durable market presence, and eventually moved its operations, or ceased its separate existence entirely. After the low-cost carrier ceased operations, American generally resumed its prior marketing strategy, and in certain markets reduced the number of flights and raised its prices, roughly to levels comparable to those prior to the period of low-fare competition. American's pricing and capacity decisions on the routes in question could have resulted in pricing its product below cost, and American might have intended to subsequently recoup these costs by supra-competitive pricing by monopolizing or attempting to monopolize these routes. -

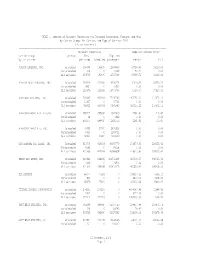

TABLE 1. Summary of Aircraft Departures and Enplaned

TABLE 1. Summary of Aircraft Departures and Enplaned Passengers, Freight, and Mail by Carrier Group, Air Carrier, and Type of Service: 2000 ( Major carriers ) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Aircraft Departures Enplaned revenue-tones Carrier Group Service Total Enplaned by air carrier performed Scheduled passengers Freight Mail -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALASKA AIRLINES, INC. Scheduled 158308 165435 12694899 63018.40 19220.01 Nonscheduled 228 0 12409 50.32 0.00 All services 158536 165435 12707308 63068.72 19220.01 AMERICA WEST AIRLINES, INC. Scheduled 204018 212692 19706774 31326.34 35926.29 Nonscheduled 8861 0 9632 0.00 0.00 All services 212879 212692 19716406 31326.34 35926.29 AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. Scheduled 769485 800908 77205742 367155.22 210672.12 Nonscheduled 21437 0 37701 0.00 0.00 All services 790922 800908 77243443 367155.22 210672.12 AMERICAN EAGLE AIRLINES,INC Scheduled 459247 499830 11623833 2261.84 713.67 Nonscheduled 28 0 1922 0.00 0.00 All services 459275 499830 11625755 2261.84 713.67 AMERICAN TRANS AIR, INC. Scheduled 49496 50210 5830539 0.00 0.00 Nonscheduled 9425 0 1189721 0.00 0.00 All services 58921 50210 7020260 0.00 0.00 CONTINENTAL AIR LINES, INC. Scheduled 413746 419998 40947770 148373.63 128123.41 Nonscheduled 9592 0 41058 0.00 0.00 All services 423338 419998 40988828 148373.63 128123.41 DELTA AIR LINES, INC. Scheduled 916463 946995 101756198 400539.37 346435.53 Nonscheduled 5156 0 74975 0.04 0.00 All services 921619 946995 101831173 400539.41 346435.53 DHL AIRWAYS Scheduled 68777 77823 0 314057.33 5305.19 Nonscheduled 802 0 0 6872.73 3338.03 All services 69579 77823 0 320930.06 8643.22 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORPORATION Scheduled 274215 274215 0 4478347.96 11348.92 Nonscheduled 2927 0 0 6177.09 0.00 All services 277142 274215 0 4484525.05 11348.92 NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC. -

The Evolution of U.S. Commercial Domestic Aircraft Operations from 1991 to 2010

THE EVOLUTION OF U.S. COMMERCIAL DOMESTIC AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS FROM 1991 TO 2010 by MASSACHUSETTS INSTME OF TECHNOLOGY ALEXANDER ANDREW WULZ UL02 1 B.S., Aerospace Engineering University of Notre Dame (2008) Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in PartialFulfillment of the Requirementsfor the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2012 0 2012 Alexander Andrew Wulz. All rights reserved. .The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author ..................................................................... .. ...................... Department of Aeronautr and Astronautics n n May 11, 2012 Certified by ............................................................................ Peter P. Belobaba Principle Research Scientist of Aeronautics and Astronautics / Thesis Supervisor A ccepted by ................................................................... Eytan H. Modiano Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Chair, Graduate Program Committee 1 PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 THE EVOLUTION OF U.S. COMMERCIAL DOMESTIC AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS FROM 1991 TO 2010 by ALEXANDER ANDREW WULZ Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 11, 2012 in PartialFulfillment of the Requirementsfor the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS ABSTRACT The main objective of this thesis is to explore the evolution of U.S. commercial domestic aircraft operations from 1991 to 2010 and describe the implications for future U.S. commercial domestic fleets. Using data collected from the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, we analyze 110 different aircraft types from 145 airlines operating U.S. commercial domestic service between 1991 and 2010. We classify the aircraft analyzed into four categories: turboprop, regional jet, narrow-body, and wide-body. -

Office of the City Secretary City of Dallas, Texas Minutes of the Dallas City Council Wednesday, March 19, 1997 97-0930 Briefing

MINUTES OF THE DALLAS CITY COUNCIL WEDNESDAY, MARCH 19, 1997 97-0930 BRIEFING MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBER, CITY HALL MAYOR RON KIRK, PRESIDING PRESENT: [15] Kirk, Wells, Mayes, Salazar, Luna, Stimson, Duncan, Hicks, Mallory Caraway, Lipscomb, Poss, Walne, Fielding, Blumer, McDaniel ABSENT: [0] The meeting was called to order at 9:12 a.m. The assistant city secretary announced that a quorum of the city council was present. The invocation was given by the Rev. Tyler Carter, pastor, Carver Heights Baptist Church. The meeting agenda, which was posted in accordance with Chapter 551, "OPEN MEETINGS," of the Texas Government Code, was presented. After all business properly brought before the city council had been considered the city council adjourned at 4:20 p.m. Assistant City Secretary The meeting agenda is attached to the minutes of this meeting as EXHIBIT A. Reports and other records pertaining to matters considered by the city council, are filed with the city secretary as official public records and comprise EXHIBIT B to the minutes of this meeting. 5/31/11 14:10 N:\DATA\MINUTES\1997\CC031997.WPD OFFICE OF THE CITY SECRETARY CITY OF DALLAS, TEXAS MINUTES OF THE DALLAS CITY COUNCIL WEDNESDAY, MARCH 19, 1997 E X H I B I T A 5/31/11 14:10 N:\DATA\MINUTES\1997\CC031997.WPD OFFICE OF THE CITY SECRETARY CITY OF DALLAS, TEXAS MINUTES OF THE DALLAS CITY COUNCIL WEDNESDAY, MARCH 19, 1997 E X H I B I T B 5/31/11 14:10 N:\DATA\MINUTES\1997\CC031997.WPD OFFICE OF THE CITY SECRETARY CITY OF DALLAS, TEXAS BRIEFING MEETING OF THE DALLAS CITY COUNCIL March 19, 1997 97-0931 Agenda item (3): Special Presentations At the beginning of each briefing meeting of the city council a time is set aside for the mayor to recognize special individuals or groups, to read mayoral proclamations, to confer honorary citizenships, and to make special presentations. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 145 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 5, 1999 No. 133 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was SCHEDULE If Congress does not reauthorize the called to order by the President pro Mr. MCCAIN. Mr. President, today Airport Improvement Program (AIP), tempore [Mr. THURMOND]. the Senate will resume consideration the Federal Aviation Administration of the pending amendments to the FAA (FAA) will be prohibited from issuing PRAYER bill. Senators should be aware that much needed grants to airports in every state, regardless of whether or The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John rollcall votes are possible today prior not funds have been appropriated. We Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: to the 12:30 recess in an attempt to have now entered fiscal year 2000, and Lord of all life, our prayer is like complete action on the bill by the end we cannot put off reauthorization of breathing. We breathe in Your Spirit of the day. As a reminder, first-degree the AIP. The program lapsed as of last and breathe out praise to You. Help us amendments to the bill must be filed to take a deep breath of Your love, Friday. Every day that goes by without by 10 a.m. today. As a further re- an AIP authorization is another day peace, and joy so that we will be re- minder, debate on three judicial nomi- freshed and ready for the day. -

Volume 22: Number 1 (2004)

Estimating Airline Employment: The Impact Of The 9-11 Terrorist Attacks David A. NewMyer, Robert W. Kaps, and Nathan L. Yukna Southern Illinois University Carbondale ABSTRACT In the calendar year prior to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, U. S. Airlines employed 732,049 people according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics [BTS] of the U. S. Department of Transportation (Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U. S. Department of Transportation [BTS], 2001). Since the 9-11 attacks there have been numerous press reports concerning airline layoffs, especially at the "traditional," long-time airlines such as American, Delta, Northwest, United and US Airways. BTS figures also show that there has been a drop in U. S. Airline employment when comparing the figures at the end of the calendar year 2000 (732,049 employees) to the figures at the end of calendar year 2002 (642,797 employees) the first full year following the terrorist attacks (BTS, 2003). This change from 2000 to 2002 represents a total reduction of 89,252 employees. However, prior research by NewMyer, Kaps and Owens (2003) indicates that BTS figures do not necessarily represent the complete airline industry employment picture. Therefore, one key purpose of this research was to examine the scope of the post 9-11 attack airline employment change in light of all available sources. This first portion of the research compared a number of different data sources for airline employment data. A second purpose of the study will be to provide airline industry employment totals for both 2000 and 2002, if different from the BTS figures, and report those. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 18-1062 In the Supreme Court of the United States LOVE TERMINAL PARTNERS, L.P., ET AL., PETITIONERS v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES IN OPPOSITION NOEL J. FRANCISCO Solicitor General Counsel of Record ERIC GRANT Deputy Assistant Attorney General WILLIAM B. LAZARUS ROBERT J. LUNDMAN Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the court of appeals erred in assessing the economic impact of government action alleged to constitute a taking based on the record evidence of the investment’s financial history under the regulatory re- strictions that existed at the time of the alleged taking. 2. Whether the court of appeals erred in determining that petitioners lacked reasonable, investment-backed ex- pectations premised on their speculation about poten- tial changes to federal law. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below .............................................................................. 1 Jurisdiction .................................................................................... 1 Statement ...................................................................................... 1 Argument ..................................................................................... 12 Conclusion ................................................................................... 23 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases: City of Dallas v.