DRAFT Port of Tacoma Northwest Ports Clean Air Strategy Implementation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3

2008 The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3 Grantees 13 Fiscal Sponsorships 28 Financial Highlights 30 Trustees and Staff 33 Committees 34 www.seattlefoundation.org | (206) 622-2294 While the 2008 financial crisis created greater needs in our community, it also gave us reason for hope. 2008 Foundation donors have risen to the challenges that face King County today by generously supporting the organizations effectively working to improve the well-being of our community. The Seattle Foundation’s commitment to building a healthy community for all King County residents remains as strong as ever. In 2008, with our donors, we granted more than $63 million to over 2000 organizations and promising initiatives in King County and beyond. Though our assets declined like most investments nationwide, The Seattle Foundation’s portfolio performed well when benchmarked against comparable endowments. In the longer term, The Seattle Foundation has outperformed portfolios comprised of traditional stocks and bonds due to prudent and responsible stewardship of charitable funds that has been the basis of our investment strategy for decades. The Seattle Foundation is also leading efforts to respond to increasing need in our community. Late last year The Seattle Foundation joined forces with the United Way of King County and other local funders to create the Building Resilience Fund—a three-year, $6 million effort to help local people who have been hardest hit by the economic downturn. Through this fund, we are bolstering the capacity of selected nonprofits to meet increasing basic needs and providing a network of services to put people on the road on self-reliance. -

The Commencement Bay Superfund Legacy: Collaboration, Restoration and Redevelopment in the Local Landscape

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2010 The ommeC ncement Bay Superfund Legacy: Collaboration, Restoration and Redevelopment in the Local Landscape Jenni Denekas University of Puget Sound Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Recommended Citation Denekas, Jenni, "The ommeC ncement Bay Superfund Legacy: Collaboration, Restoration and Redevelopment in the Local Landscape" (2010). Summer Research. Paper 51. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/51 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Commencement Bay Superfund Legacy: Collaboration, Restoration and Redevelopment in the Local Landscape Jenni Denekas 2010 Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Summer Research Grant Recipient I. Introduction Commencement Bay has a long history of industrial development, which has leant Tacoma its moniker “City of Destiny” as well as its notoriety as the home of the “Tacoma aroma.” This development has also shaped Tacoma’s current shoreline and overall appearance. Originally, the shoreline was primarily an expanse of tideflats and estuaries, with large shellfish and seabird populations and important salmon habitat. The tideflats have for thousands of years supported tribes such as the Puyallup, and more recently the region’s abundant natural resources and the deep waters of the bay enticed Western settlement. In spite of the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek, which supposedly granted the Puyallup the rights to the tideflats at the mouth of the Puyallup River, development by Western settlers quickly overtook the local landscape. -

On May 15, 1967; And

RESOLUTION NO. 2854 A RESOLUTION of the Port Commission of the Port of Seattle Celebrating the 15th Anniversary of the Sister-Port Affiliation Between the Port of Kobe and the Port of Seattle WHEREAS, Resolution No. 2258 creating the Port of Kobe and Port of Seattle Sister Port Affiliation was adopted by the Port Commission of the Port of Seattle and signed by President Merle D. Adlum of the Port of Seattle Commission on May 15, 1967; and WHEREAS, the friendly and mutually rewarding relationship between the Port of Kobe and the Port of Seattle has continued to deepen and become increasingly meaningful; and WHEREAS, the exchange of marketing and trade information, the sharing of modem transportation and distribution technologies, and the hospitality shown visiting trade delegations have facilitated the continued development of interna- tional commerce between the City of Kobe and the City of Seattle; and WHEREAS, as evidenced by the celebration of the 25th anniversary of the sister city relationship between the City of Kobe, Japan and the City of Seattle, Washington, U.S.A., there is an enduring friendship between the peoples of Kobe and Seattle; and WHEREAS, a delegation representing the Port of Seattle is visiting Kobe in May, 1982 to honor the 15th anniversary of their Sister Port relationship; NOW, THEREFORE, be it resolved that the undersigned express their considerable pleasure and pride in noting the cordial friendship and the rewarding commercial relationship that has developed between the Port of Seattle and the Port of Kobe as a result of the action taken 15 years ago initiating the Sister Port Affiliation. -

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation As a National Heritage Area

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION APRIL 2010 The National Maritime Heritage Area feasibility study was guided by the work of a steering committee assembled by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Steering committee members included: • Dick Thompson (Chair), Principal, Thompson Consulting • Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation • Chris Endresen, Office of Maria Cantwell • Leonard Forsman, Chair, Suquamish Tribe • Chuck Fowler, President, Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council • Senator Karen Fraser, Thurston County • Patricia Lantz, Member, Washington State Heritage Center Trust Board of Trustees • Flo Lentz, King County 4Culture • Jennifer Meisner, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation • Lita Dawn Stanton, Gig Harbor Historic Preservation Coordinator Prepared for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation by Parametrix Berk & Associates March , 2010 Washington State NATIONAL MARITIME HERITAGE AREA Feasibility Study Preface National Heritage Areas are special places recognized by Congress as having nationally important heritage resources. The request to designate an area as a National Heritage Area is locally initiated, -

Consent Decree

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 9 t0 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 11 Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) 12 ) F.O.F INC, ) 13 ) ¯HYLEBOS WATERWAY ) PROBLEM AREAS 14 ) Defendant. ) 15 ) 16 17 TABLE OF CONTENTS 18 A. BACKGROUND .......................................................................................... ........................3 19 B. JURISDICTION ................................................................. ...................................................8 20 C. PARTIES BOUND ...............................................................................................................8 21 D. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE ..............................................................................................8 22 E. DEFINITIONS .....................................................................................................................9 23 F. PAYMENT ..........................................................................................................................13 24 G. FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH CONSENT DECREE ...................................................;I7 25 H. CERTIFICATION OF SETTLING DEFENDANT AND C()NSENT DECREE United States Department of Justic Commencement Bay Nearshore/Tideflats Environment and Natural Resources Divisior Superfund Site Environmental Enforcement Sectior P.O. Box 7611 Page 1 of 25 Ben Franklin Statior Washington, D.C. 20044-761 1 SETYLING FEDERAL AGENCIES ............................................................................19 -

October 2019

October 2019 Community Attributes Inc. tells data-rich stories about communities that are important to decision makers. President and CEO: Chris Mefford Project Manager: Michaela Jellicoe Analysts: Madalina Calen Spencer Cohen, PhD Diana Haring Maureen McLennon Carrie Schaden Zack Tarhouni Community Attributes Inc. 500 Union Street, Suite 200 Seattle, Washington 98101 www.communityattributes.com October 2019 E XECUTIVE S UMMARY The Ports of Seattle and Tacoma combined represent a core economic development asset for businesses and communities in Washington state and elsewhere in the U.S. Both ports facilitate the movement of millions of twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of containerized cargo as well as millions of metric tons of breakbulk, automobiles, logs, and liquid bulk. Both ports are also host to industrial and non-industrial activities that spur job growth and economic wealth creation in the Central Puget Sound and Washington state. The Port of Seattle facilities support a large and growing cruise ship industry and serve approximately half of the North Pacific Fisheries Fleet. Exhibit E1. Estimated Direct Impacts of Activities at The Northwest Seaport Alliance, Port of Seattle, and Port of Tacoma, Washington, 2017 and 2019 Business Labor Income Jobs Output (mils) (mils) The Northwest Seaport Alliance (2017) 20,100 $5,858.7 $1,902.7 Containerized Cargo 14,900 $4,537.6 $1,502.5 Automobiles 1,300 $308.8 $108.4 Breakbulk, Logs and Other Cargo 3,900 $1,012.2 $291.9 Port of Seattle Cruise Industry (2019, 2018$) 3,000 $467.8 $122.7 Port of Seattle Commercial Fishing (2017) 7,200 $671.3 $313.4 Port of Seattle Recreational Marinas and Other Business (2017) 3,600 $728.8 $357.2 Port of Tacoma Tenants and Other Business (2017) 1,500 $852.2 $114.3 Sources: Puget Sound Regional Council, 2019; Washington State Employment Security Department, 2018; Washington State Department of Revenue, 2018; The Northwest Seaport Alliance, 2018; Port of Seattle, 2018; Port of Tacoma, 2018; Community Attributes Inc., 2019. -

Draft Northwest Seaport Alliance Northwest Ports Clean Air Strategy Implementation Plan

DRAFT Northwest Ports Clean Air Strategy Implementation Plan Produced by the Northwest Seaport Alliance June 30, 2021 Executive Summary: PLACEHOLDER PLACEHOLDER i Table of Contents: PLACEHOLDER PLACEHOLDER ii Glossary: PLACEHOLDER PLACEHOLDER iii 1. Purpose The Northwest Seaport Alliance (NWSA) is committed to reducing, and ultimately eliminating, the air and climate pollution emissions of diesel particulate matter (DPM) and greenhouse gases (GHG) – that are associated with the cargo shipping operations that we manage on behalf of the ports of Tacoma and Seattle. That is why The NWSA, at its inception in 2015, joined the Northwest Ports Clean Air Strategy (NWPCAS). The NWPCAS is a voluntary collaboration between the four largest port entities of the Pacific Northwest – NWSA, Port of Tacoma (PoT), Port of Seattle (PoS), and Port of Vancouver (VFPA) – to reduce air and climate pollution from their respective seaport activities throughout the Puget Sound – Georgia Basin Airshed. The NWPCAS constitutes a shared strategic framework for clean air and climate actions and investments that creates a “level playing field” across the four participating port entities, and helps them coordinate, collaborate, and hold each other accountable. The participating ports updated and renewed the NWPCAS in 2020, strengthening their commitment to reducing air and climate pollution. The 2020 NWPCAS puts forth an ambitious, aspirational, joint vision to phase out emissions from seaport activities by 2050, and a suite of high-level joint objectives and actions to advance that vision. In addition, each of the four participating port entities committed to developing a detailed implementation plan tailored to their particular policy environments, governance structures, lines of business, emissions profiles, and community priorities. -

Motion 09611

-., .. ~ ~ ~.! .. ~ ~~, '" • ~ 1 L:\RRY PHllUP$ , KENT PULLE.N LOUISE MILLI:Fi 1 June 2.1995 INTRODUCED BY: BRUCE LAING 2 II CRD/lLK PROPOSED NO: 95 - 44 1 3 4 MOTION NO. 9 611 .:J 5 A MOTION approving projects for the King County Cultural Facilities Program, 6 in accordance with Ordinance 10189. 7 WHEREAS, the King County arts commission and landmarks and heritage commission 8 are authorized by Ordinance 10189 to administer cultural facilities projects, and 9 WHEREAS, the King County cultural resources division received 87 applications 10 requesting $8,639,677 fromthe 1995 Cultural Facilities Program and County.Council's Arts 11 and Natuml Resources Initiative. and 12 WHEREAS, two review panels of arts and heritage professionals, coro.munity 13 representatives, and commission representatives reviewed the applications and made 14 recommendations to the King County arts commission and landmarks and heritage 15 commission, as listed in Attachments A (arts) and B (heritage), and 16 WHEREAS, the Kin~ County arts commission and the King County landmarks and 17 heritage commission approved the review panels' recommendations, and 18 WHEREAS, the recommendations for arts and heritage Cultural Facilities Program 19 funding adhere to the guidelines and fmancial plan policies approved by the King County 20 council in Motion 8797, and 21 WHEREAS, the fmancial plan inc1u~ed as Attachment C, has been revised to indicate 22 actual hoteVmotel tax revenue. for 1994 and projected revenue consistent with assumptions 23 made in the 1995 adopted budget, and 24 WHEREAS, the financial, plan supports Cultural Facilities program funding; 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 , ' ( -~ f" ," '\ , 9611 ~ I " NOW THEREFORE BE IT MOVED by the Council of King County: 2 The executive is hereby authorized to allocate a total of $727,399, which includes 3 $512,200 for twenty arts projects as listed in Attachment A for Cultural Facilities program arts ~ projects and $215,199 for eight heritage projects as listed in Attachment B for Cultural .S Facilities program heritage projects. -

Kent Roberts, Schwabe, Williamson and Wyatt

16th Biennial National Harbor Safety Committee Conference Hylebos Waterway Sunken Rock Barge Kent Roberts Schwabe, Williamson and Wyatt Portland/Seattle/Vancouver Port of Tacoma Hylebos Waterway at Tacoma Upper End Hylebos Waterway Schnitzer Steel Recycling Metals Export Terminal Schnitzer Steel Terminal Buffelin Turn Hylebos navigation channel • 200’ wide navigation channel • USACE maintained at 30’ MLLW • “38’ Channel” = Ship drafts at high tide to 35’ with 3’ under keel clearance Channel widens to 250’ at Buffelin Turn – Walrath Dock Walrath Trucking Sound Rock Products SeaLevel Bulkhead Builders, Inc. SeaLevel Bulkhead Builders, Inc. November 6, 2016 SLBB Rock Barge “COMPLIANT” 145 x 45 x 11 steel deck barge Built 1966 Rock Barge Load • 235 Excavator • 2 loading ramps • 350 tons 6-man granite rock 6-man rock = 6,000 – 8,000 lbs outer dimensions 54” to 60” Value approx. $4600 Rock Barge, morning of Nov. 6 Sunken Rock Barge Salvage Plan • Global Diving & Salvage November 11, SLBB Rock Barge Wreck Removal • Detailed plan to refloat and remove the Rock Barge. • Detailed plan for pre-removal and post removal sediment sampling to confirm contaminated sediments not spread/exposed. Commencement Bay Superfund Site • In 1983, EPA put Commencement Bay on its “Superfund” list as the Commencement Bay Nearshore/Tide Flats site. • Decades long clean-up effort with ongoing monitoring. • 2 of 9 sediment sites of highest concern in Hylebos Waterway. Commencement Bay Superfund Site • 2014 EPA/USACE site assessment determined not to dredge Buffelin Turn upslope due to natural, clean sediment capping of subsurface contaminated sediments. Barge Removal Salvage Plan • “The 6-man rock cargo from the submerged barge was located offshore and embedded into the mud with less than 3.5 extending above the mud ( 25 feet below MLLW). -

A Case Study Intermodal Issues Facing the Puget Sound Region

A Case Study Of the Intermodal Issues Facing The Puget Sound Region and The Port of Seattle Patrick Sherry, Ph.D. Joseph Szyliowicz, Ph.D. Andy Goetz, Ph.D. Page McCarley University of Denver December 21, 2006 - 1 - Acknowledgments This project was supported in part by The Intermodal Task Force of the Transportation Working Group of the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation The Port of Seattle The Freight Mobility Strategic Investment Board And the Intermodal Transportation Institute of the University of Denver - 2 - Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................................................5 LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................6 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................6 PURPOSE OF THE CASE STUDY............................................................................................................................6 REGIONAL OVERVIEW.........................................................................................................................................9 GEOGRAPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS........................................................................................................10 -

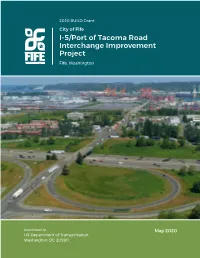

I-5/Port of Tacoma Road Interchange Improvement Project Fife, Washington

2020 BUILD Grant City of Fife I-5/Port of Tacoma Road Interchange Improvement Project Fife, Washington Submitted to May 2020 US Department of Transportation Washington, DC 20590 2020 BUILD Application May 18, 2020 Secretary Elaine L. Chao U.S. Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, D.C. 20590 Dear Secretary Chao: The City of Fife is pleased to submit this FY 2020 Better Utilizing Investment to Leverage Development (BUILD) grant application for Phase II of the I-5/Port of Tacoma Road Interchange Improvement Project (Project). This Interchange Improvement Project completes this phase of a transformational effort by the City of Fife, the Port of Tacoma, and The Washington State Department of Transportation to address significant backups at this interchange and to dramatically improve the movement of freight and goods as well as traffic in general. The Project includes road, intersection, and intersection improvements at the I-5/Port of Tacoma Road interchange that will greatly enhance a critical connection to the Port of Tacoma, which combines with the Port of Seattle to form the fourth largest gateway for containerized cargo in our nation. This $25 million in requested investment will leverage $24.65 million secured local and state matching funds already allocated to fully fund Phase II of the I-5/Port of Tacoma Road Interchange Improvement Project, making federal FY 2020 BUILD funds the last dollars needed to expeditiously complete design and begin construction. Additionally, the City of Fife has already fully funded Phase I of the Project ($44.6 million) which is 80% complete. -

Lightship No. 83 (Lv 83 Wal 508)

LIGHTSHIP NO. 83 HAER No. WA-175 (LV 83 WAL 508) Lightship BLUNTS Lightship SAN FRANCISCO Lightship RELIEF SWIFTS URE) South Lake Union Pier Seattle King County Washington PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C St. NW Washington, DC 20240 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD LIGHTSHIP No. 83 (LV 83) c,vAL sos) (Lightship BLUNTS) (Lightship SAN FRANCISCO) (Lightship RELIEF) (SWIFTS URE) HAER No. WA-175 LOCATION: South Lake Union Pier, Seattle, King County, Washington RIG/TYPE OF CRAFT: Lightship OFFICIAL NUMBERS: LV 83, WAL 508 PRINCIPAL DIMENSIONS: Length: 129' (112' as built in 1904) Beam: 28'-6" Depth: 12'-6" DATE OF CONSTRUCTION: 1904 DESIGNER: United States Office of the Light-House Board, C.J. Hutchins, Capt. U.S.N. Naval Secretary BUILDER: New York Shipbuilding Company, Camden. New Jersey SIGNIFICANCE: Lightship No. 83 is one of three surviving lightships and "the oldest on the West Coast." Of the three surviving lightships. "only No. 83 has retained her original marine steam engine and machinery, and hence is not only one of the oldest surviving American lightships, but also the lightship with the greatest integrity of design and form." 1 PROJECT INFORMATION: The Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) is a part of the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering 1 Information from U.S. Coast Guard, http://www.uscg.mil/hq/g-cp/history/weblightships/lv83.html, accessed March 2005. Quote from James Delgado, "Lightship No. 83," National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Maritime Heritage of the United States NHL Study-Large Vessels, July J 988, statement of significance.