Bushwhacking Through Narcissism: the Making of a Jungian Analyst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Oroonoko Or the Royal Slave a True History

Aphra Behn O R O O N O K O A True History Contents The Epistle Dedicatory Oroonoko Or The Royal Slave A True History Follow Penguin APHRA BEHN Born c. 1640, Canterbury, England Died 1689, London, England Taken from Oroonoko, edited by Janet Todd and published in Penguin Classics in 2003. APHRA BEHN IN PENGUIN CLASSICS Oroonoko, The Rover and Other Works Oroonoko The Epistle Dedicatory To the Right Honourable the Lord Maitland. My Lord, Since the world is grown so nice and critical upon dedications, and will needs be judging the book by the wit of the patron, we ought, with a great deal of circumspection, to choose a person against whom there can be no exception; and whose wit and worth truly merits all that one is capable of saying upon that occasion. The most part of dedications are charged with flattery; and if the world knows a man has some vices, they will not allow one to speak of his virtues. This, my Lord, is for want of thinking rightly; if men would consider with reason, they would have another sort of opinion and esteem of dedications, and would believe almost every great man has enough to make him worthy of all that can be said of him there. My Lord, a picture-drawer, when he intends to make a good picture, essays the face many ways and in many lights before he begins; that he may choose, from the several turns of it, which is most agreeable, and gives it the best grace; and if there be a scar, an ungrateful mole, or any little defect, they leave it out, and yet make the picture extremely like. -

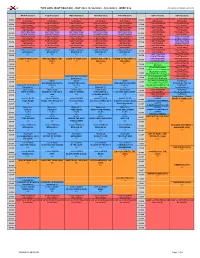

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

Mothers Grimm Free

FREE MOTHERS GRIMM PDF Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mother Goose & Grimm/Mike Peters Website The following is a list of the cast and characters from the NBC television series Grimm. Nicholas Burkhardt played by David Giuntoli is the show's protagonist and titular Grimm. Nick is a homicide detective who discovers he is descended from a line of Grimms : hunters who fight supernatural forces. Even before his abilities manifested, Nick Mothers Grimm an exceptional ability to make quick Mothers Grimm accurate deductions about the motivations and pasts of individuals. This power has now expressed itself as his ability to perceive the Mothers Grimm that nobody else can see. Nick had wanted to propose to his girlfriend, Juliette, for some time, but he felt that he Mothers Grimm have to tell her about his life as a Grimm beforehand. Throughout the first season, Nick struggles to maintain balance Mothers Grimm his normal life and his life as a grimm. The two tend to cross when he works cases that involve wesenwhich are the creatures of the grimm world. As Nick dives deeper into his grimm heritage, he begins to train with Monroe to learn about the wesen Mothers Grimm Portland and to use the Mothers Grimm that his aunt Marie left behind. As of episode 19, Nick had successfully killed three reaperscreatures that are sent out to kill grimms hence the grimm reaper title. He kills the first in defense of Marie, and the other two are killed in self-defense after being sent Nick's lead suspect in a case. -

The Neidhart Plays: a Social and Theatrical Analysis

THE NEIDHART PLAYS: A SOCIAL AND THEATRICAL ANALYSIS By VICTOR RENARD COOK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1969 iliBiiii||ll ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Assistiince from Mr. Jesse R. Jones, Jr., of the Graduate Research Library at the University of Florida is acknowledged and deeply appreciated. To the members of his examining committee, Professors G. Paul Moore, C. Frank Karns , and Jam.es Lauricella, the writer offers his thanks. He is particularly grateful to Professors Sarah Robinson of the Department of Antliropology and Melvin Valk of the Department of Germxtn, for the i;ij,.e they spent reading draft copies of this study. Their suggestions and advice concerning the sociological and philological aspects of the subject were invaluable. Finally, the writer acknowledges the debt he owes Professor L. L. Zim.merman, the principle director of this study. Professor Zimmerman's patience, wisdom., and good Iium.or made com.pletion of this work possible. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE. THE SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE NEIDHART PLAYS. Chapter I. THE NEIDR/\RT PLAYS AS SOCIAL DOCUMENTS 14 II. THE ORIGINS OF THE CONFLICT 37 III. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NEIDHART LEGEND 58 PART TWO. THE NEIDHART PLAYS AS WORKS OF THEATRICAL ART. IV. THE THEATRICAL ORIGINS 0^-^ THE NEIDHART PLAYS .... 86 V. THE DESCRIPTIVE AiNALYSIS OF THE NEIDHART PLAYS ... 110 VI. THE THEATRICAL FORiM OF THE NEIDHART FLAYS 130 CONCLUSIONS 156 APPENDIX A 160 APPENDIX B 162 APPENDIX C 224 APPENDIX D 231 BIBLIOGRAPHY 253 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 262 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to expose the social and theatrical significance of four of the five extant late medieval German dramatic works based on the legendary character of Neidhart. -

Dasha Shishkin B

Dasha Shishkin b. 1977, Moscow, Russia Lives and works in New York, NY Education MFA, Columbia University, New York, NY 2006 BFA, New School for Social Research, New York, NY 2001 Solo Exhibitions 2010 Dap, Giò Marconi, Milan, Italy 2009 Men Like That, Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, NY 2007 Love Sick, Andreas Grimm, Munich, Germany First Sorrow, Kantor/Feuer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2006 W.A.M. Who Gives A Damn If You Procreate, Grimm|Rosenfeld, New York, NY 2004 Drawings and Prints, Grimm|Rosenfeld, Munich, Germany 2002 On Mistrust and Suspicion of Children, in General, ND Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Group Exhibitions 2011 Monanism, Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania, Australia 2010 Living with Art: Collecting Contemporary in Metro New York, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, NY Wildly Different Things: New York and Dublin, The Observatory, Dublin, Ireland The More I Draw, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Siegen, Germany 2009 Embrace, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO A Decade of Contemporary American Printmaking: 1999-2009, Visual Art Center of Academy of Arts and Design, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China 1999, China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA 2008 Once Upon A Time, ISE Cultural Foundation, New York, NY Drawing Now – Drawing Then Young Masters – Old Masters, Arndt & Partner, Zurich, Switzerland Nightmares & Dreamscapes, Galleria, Alberto Peola Gallery, Turin, Italy 2007 The Four Horsemen, Galerie Im Regierungsviertel, Turin, Italy World Receiver, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany Panic Room: Works from the Dakis Joannou Collection, Athens, -

The American Legion – Department of Oregon

Department of Oregon History of 1921 The Department of Oregon The American Legion History of 1921 The 100th Anniversary of The American Legion 1919-2019 The Department of Oregon PO Box 1730 Wilsonville, OR. 97070-1730 503.685.5006 www.orlegion.org This document was produced on behalf of the Department’s 17,000 members, the wartime veterans of the 20th and 21st centuries, who can be found in 117 posts in communities across our great state. Compiled and edited by Eugene G. Hellickson Department Commander 2017 – 2018 Version 1921.1.1 2 THE RED POPPY FOR MEMORIAL DAY “Poppies in the wheat fields and the pleasant hills of France Reddening in the summer breeze that bid them not and dance.” So sang the soldier poet of the A.E.F.F. that blazing summer of 1918 when an unleashed American army was writing the Oureq and Vesle into our history. He sang of the poppies because it was through machinegun raked fields of them that the doughboys were charging; he sang of them because the doughboys were wearing them in their helmets as they roared ahead. Not all of us were along the Oureq and the Vesle that summer, taking German strong points with poppies in our helments, but every American can wear his poppy this Memorial Day, when the poppy, as the offical memorial flower of the American Legion, will blossom in hundreds of thousands of loyal lapels. The American who wears the poppy on Memorial Day is showing that he has not forgotten; for he wears it to remember – “Poppies in the wheat fields; how still beside them lie Scattered forms that stir not when the star shells burst on high; Bently bending o’er them beneath the moon’s soft glance “Poppies in the Wheat fields; how still ransomed hills of France.” The Red Poppy is the Offical Memorial Flower. -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart. -

Master Or Servant? Stockwell, Trefor

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Magical realism : master or servant? Stockwell, Trefor Award date: 2012 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 4 Magical Realism: Master or Servant? Trefor Stockwell Submission for the degree of PhD 2012 Bangor University 5 Abstract This study seeks to show the process of development by which my writing of this series of short stories has responded to my relationship to a welcoming, albeit alien, culture; namely: a small mountain village in south west Bulgaria. It also explores my responses to living and working within that culture, and the ways in which my studies of the folk culture, history and the impact of western culture on existing cultural beliefs and values have also affected both my writing and my own rather ambiguous cultural background (see introduction p. -

Impossible Communities in Prague's German Gothic

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2019 Impossible Communities in Prague’s German Gothic: Nationalism, Degeneration, and the Monstrous Feminine in Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem (1915) Amy Michelle Braun Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, German Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Braun, Amy Michelle, "Impossible Communities in Prague’s German Gothic: Nationalism, Degeneration, and the Monstrous Feminine in Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem (1915)" (2019). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1809. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures Program in Comparative Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: Lynne Tatlock, Chair Elizabeth Allen Caroline Kita Erin McGlothlin Gerhild Williams Impossible Communities in Prague’s German Gothic: Nationalism, Degeneration, and the Monstrous Feminine in Gustav Meyrink’s -

John Collet (Ca

JOHN COLLET (CA. 1725-1780) A COMMERCIAL COMIC ARTIST TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I CAITLIN BLACKWELL PhD University of York Department of History of Art December 2013 ii ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the comic work of the English painter John Collet (ca. 1725- 1780), who flourished between 1760 and 1780, producing mostly mild social satires and humorous genre subjects. In his own lifetime, Collet was a celebrated painter, who was frequently described as the ‘second Hogarth.’ His works were known to a wide audience; he regularly participated in London’s public exhibitions, and more than eighty comic prints were made after his oil paintings and watercolour designs. Despite his popularity and prolific output, however, Collet has been largely neglected by modern scholars. When he is acknowledged, it is generally in the context of broader studies on graphic satire, consequently confusing his true profession as a painter and eliding his contribution to London’s nascent exhibition culture. This study aims to rescue Collet from obscurity through in-depth analysis of his mostly unfamiliar works, while also offering some explanation for his exclusion from the British art historical canon. His work will be located within both the arena of public exhibitions and the print market, and thus, for the first time, equal attention will be paid to the extant paintings, as well as the reproductive prints. The thesis will be organised into a succession of close readings of Collet’s work, with each chapter focusing on a few representative examples of a significant strand of imagery. These images will be examined from art-historical and socio-historical perspectives, thereby demonstrating the artist’s engagement with both established pictorial traditions, and ephemeral and topical social preoccupations.