The Oswald Review of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: Volume 23, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Curriculum Leadership Capacity-Building Through Biographical Narrative: a Currere Case Study

EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Karl W. Martin August 2018 © Copyright, 2018 by Karl W. Martin All Rights Reserved ii MARTIN, KARL W., Ph.D., August 2018 Education, Health and Human Services EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY (473 pp.) My dissertation joins a vibrant conversation with James G. Henderson and colleagues, curriculum workers involved with leadership envisioned and embodied in his Collegial Curriculum Leadership Process (CCLP). Their work, “embedded in dynamic, open-ended folding, is a recursive, multiphased process supporting educators with a particular vocational calling” (Henderson, 2017). The four key Deleuzian “folds” of the process explore “awakening” to become lead professionals for democratic ways of living, cultivating repertoires for a diversified, holistic pedagogy, engaging in critical self- examinations and critically appraising their professional artistry. In “reactivating” the lived experiences, scholarship, writing and vocational calling of a brilliant Greek and Latin scholar named Marya Barlowski, meanings will be constructed as engendered through biographical narrative and currere case study. Grounded in the curriculum leadership “map,” she represents an allegorical presence in the narrative. Allegory has always been connected to awakening, and awakening is a precursor for capacity-building. The research design (the precise way in which to study this ‘problem’) will be a combination of historical narrative and currere. This collecting and constructing of Her story speaks to how the vision of leadership isn’t completely new – threads of it are tied to the past. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Constructing Womanhood: the Influence of Conduct Books On

CONSTRUCTING WOMANHOOD: THE INFLUENCE OF CONDUCT BOOKS ON GENDER PERFORMANCE AND IDEOLOGY OF WOMANHOOD IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S NOVELS, 1865-1914 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Thorndike May 2015 Copyright All rights reserved Dissertation written by Colleen Thorndike B.A., Francis Marion University, 2002 M.A., University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Wesley Raabe, Associate Professor, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Babacar M’Baye, Associate Professor, Department of English Stephane Booth, Associate Provost Emeritus, Department of History Kathryn A. Kerns, Professor, Department of Psychology Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Conduct Books ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2 : Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Advice for Girls .......................................... 41 Chapter 3: Bands of Women: -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Mabel Normand

Mabel Normand Also Known As: Mabel Fortescue Lived: November 9, 1892 - February 23, 1930 Worked as: co-director, comedienne, director, film actress, producer, scenario writer Worked In: United States by Simon Joyce, Jennifer Putzi Mabel Normand starred in at least one hundred and sixty-seven film shorts and twenty-three full- length features, mainly for Mack Sennett’s Keystone Film Company, and was one of the earliest silent actors to function as her own director. She was also one of the first leading performers to appear on film without a previous background in the theatre (having begun her career in modeling), to be named in the title of her films (beginning with 1912’s Mabel’s Lovers), and to have her own studio (the ill-fated Mabel Normand Feature Film Company). That her contributions to early film history are not better known is attributable in part to her involvement in the Hollywood scandals of the 1920s, and in part to our reliance on the self-interested memoirs of her better-known colleagues (especially Sennett and Charlie Chaplin) following her death at age thirty-eight. It is hard to get an accurate picture from such questionable and contradictory recollections, or from interviews with Normand herself, filtered as they often were through a sophisticated publicity operation at Keystone. Film scholars who have worked with these same sources have often proved just as discrepant and unreliable, especially in their accounts of her directorial contributions. Normand’s early career included stints at the Biograph Company, working with D. W. Griffith, and at the Vitagraph Company, yet it was her work at Keystone that solidified her image as slapstick comedienne. -

Bushwhacking Through Narcissism: the Making of a Jungian Analyst

Bushwhacking Through Narcissism: The Making of a Jungian Analyst by John Ryan Haule Copyright © 1993 All Rights Reserved http://www.jrhaule.net/bushwhack.html One Mara Probably every analyst can cite a small number of analysands whose work has taught him or her what analysis is all about. For regardless of the books we have read and the number of years spent in training, it is only when we face another psyche entirely on our own that the realities of our profession begin to dawn on us. The dialogue between two souls is a dissolving experience. The extent to which we allow ourselves into it corresponds to our ability to tolerate fragmentation and confusion. Jung often referred to this experience as "the soup," where onions, potatoes, carrots, herbs, and meat, mingle their flavors to produce a delectable and nourishing broth. In an analysis of this sort, both psyches are softened and give up some of their essence to the process. It is widely known that this can be a terrifying experience for an analysand with a weak sense of self. But the analyst is supposed to have been analyzed and to have developed thereby a real confidence in the ego-self axis and furthermore to be "contained" by a flexible and coherent familiarity with the models and theory of analysis. Ideally this conception suffices. The analysand meets our expectations, and we can rely on the customary maps of soulscape we have learned from our training and general life experience. If we have to depart from familiar paths, the compass we forged in our own analysis keeps us oriented. -

Kate Chopin and Feminism: the Significance of Water

Kate Chopin and Feminism: the Significance of Water 1* Brittany Groves B.A. Candidate, Department of English, California State University Stanislaus, 1 University Circle, Turlock, CA 95382 Received 16 April 2019; accepted May 2019 Abstract Late nineteenth century writer Kate Chopin in her time was commonly recognized as a regionalist or realist author, focusing on the lifestyle and setting of the Louisiana region. An author’s intentions are extremely important.The way a writer crafts a story is telling of how that person views the world they are in. Because of this, although she did not directly advocate for it, she should be considered a feminist writer as well. Chopin’s writing tells the story of women claiming their own independence in the only ways they can in patriarchal society. Within that, she uses water in many of her stories as a representation of independence and baptism into a new way of life. Most of the female characters who have an experience with water, also act in a way that goes against the societal norm for each situation. Even though Chopin made her career through the use of regionalism and realism (Chopin and Levine et al. 441), it does not take away from the fact that she was representing women in her stories as fighting for their independence in their own ways. While regionalism and realism are very important parts to understanding Chopin as a writer, the fact that she, in her own way, advocates for women to have their own agency is also a huge part of her writing. -

Oroonoko Or the Royal Slave a True History

Aphra Behn O R O O N O K O A True History Contents The Epistle Dedicatory Oroonoko Or The Royal Slave A True History Follow Penguin APHRA BEHN Born c. 1640, Canterbury, England Died 1689, London, England Taken from Oroonoko, edited by Janet Todd and published in Penguin Classics in 2003. APHRA BEHN IN PENGUIN CLASSICS Oroonoko, The Rover and Other Works Oroonoko The Epistle Dedicatory To the Right Honourable the Lord Maitland. My Lord, Since the world is grown so nice and critical upon dedications, and will needs be judging the book by the wit of the patron, we ought, with a great deal of circumspection, to choose a person against whom there can be no exception; and whose wit and worth truly merits all that one is capable of saying upon that occasion. The most part of dedications are charged with flattery; and if the world knows a man has some vices, they will not allow one to speak of his virtues. This, my Lord, is for want of thinking rightly; if men would consider with reason, they would have another sort of opinion and esteem of dedications, and would believe almost every great man has enough to make him worthy of all that can be said of him there. My Lord, a picture-drawer, when he intends to make a good picture, essays the face many ways and in many lights before he begins; that he may choose, from the several turns of it, which is most agreeable, and gives it the best grace; and if there be a scar, an ungrateful mole, or any little defect, they leave it out, and yet make the picture extremely like. -

500 Years Later Subtitles

Movie Description: 500 Years Later Program: LACAS Languages Location: Subtitles: No Subtitles Languages: Movie Description: A Royal Affair Program: World Languages Languages Location: Subtitles: No Subtitles Languages: Movie Description: A Royal Affair Program: World Languages Languages Location: HO G03 Subtitles: No Subtitles Languages: Movie Description: A Son of Africa Program: African Studies Languages Location: Turner 210 Subtitles: No Subtitles Languages: Movie Description: A Sunday in Kigali Spring 1994, Kigali, Rwanda's capital city, deep in the heart of Africa. Bernard Valcourt is a man divided between hope and disillusionment. In Africa to shoot a documentary on the devastation wreaked by AIDS, Valcourt watches on as tensions rapidly escalate between Tutsis and Hutus. At the Hotel Des Mille Program: World Languages Collines, home to expatriates, Valcourt falls madly in love with Gentille, a beautiful Rwandan waitress. Though she feels the same way, their romance grows in fits and starts; she is so young and he - he is so Languages French Location: HO 311 white.. In spite of their differences, Gentille and Valcourt throw caution to the wind and marry. And then war breaks out. Amidst the ensuing chaos the lovers are brutally separated. Valcourt searchesdesperately for his wife, but because of his staus as a foreigner, is forced to leave the country. Months later, Rwanda is stained with the blood of close to a million Tutsis but order has been restored. Valcourt returns to Kigali in search of his wife. But with many survivors displaced from their homes and some living in refugee camps across borders, his task is a difficult one. -

International Initiatives Committee Book Discussion

INTERNATIONAL INITIATIVES COMMITTEE BOOK DISCUSSION POSSIBILITIES Compiled by Krista Hartman, updated 12/2015 All titles in this list are available at the MVCC Utica Campus Library. Books already discussed: Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. (Nigeria ; Fiction) Badkken, Anna. Peace Meals: Candy-Wrapped Kalashnikovs and Other War Stories. Cohen, Michelle Corasanti. The Almond Tree. (Palestine/Israel/US ; Fiction) Hosseini, Khaled. A Thousand Splendid Suns. (Afghanistan ; Fiction) Lahiri, Jhumpa. The Namesake. (East Indian immigrants in US ; Fiction) Maathai, Wangari. Unbowed: a Memoir. (Kenya) Menzel, Peter & D’Alusio, Faith. Hungry Planet: What the World Eats. Barolini, Helen. Umbertina. (Italian American) Spring 2016 selection: Running for My Life by Lopez Lomong (Sudan) (see below) **************************************************************************************** Abdi, Hawa. Keeping Hope Alive: One Woman—90,000 Lives Changed. (Somalia) The moving memoir of one brave woman who, along with her daughters, has kept 90,000 of her fellow citizens safe, healthy, and educated for over 20 years in Somalia. Dr. Hawa Abdi, "the Mother Teresa of Somalia" and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, is the founder of a massive camp for internally displaced people located a few miles from war-torn Mogadishu, Somalia. Since 1991, when the Somali government collapsed, famine struck, and aid groups fled, she has dedicated herself to providing help for people whose lives have been shattered by violence and poverty. She turned her 1300 acres of farmland into a camp that has numbered up to 90,000 displaced people, ignoring the clan lines that have often served to divide the country. She inspired her daughters, Deqo and Amina, to become doctors. Together, they have saved tens of thousands of lives in her hospital, while providing an education to hundreds of displaced children. -

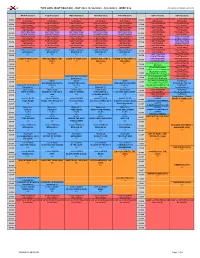

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract