The Neidhart Plays: a Social and Theatrical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camp Wanna-Read: Program Guide for the Texas Reading Club 1991. INSTITUTION Texas State Library, Austin

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 337 135 IR 015 121 AUTHOR Switzer, Robin Works TITLE Camp Wanna-Read: Program Guide for the Texas Reading Club 1991. INSTITUTION Texas State Library, Austin. Dept. of Library Development. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 273p.; For the 1990 program guide, see ED 326 245. PUB TYPE Guides - Nun-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; *Childrens Libraries; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Films; Guidelines; Handicrafts; *Library Planning; Library Services; Preschool Children; Program Development; Public Libraries; Reading Games; *Reading Programs; *Recreational Reading; State Programs IDENTIFIERS *Texas Reading Club ABSTRACT Camp Wanna-Read is the theme for the 1991 program for the Texas Reading Club, which centers around the experIences and types of things that happen at summer camp. Each chapter is a type of camp a child might attend such as cooking camp, art camp, music camp, science camp, Indian ..:amp, nature camp, and regular summer camp. The chapters are divided by program and age level. In each chapter there are themes, ideas, and books for programs for children from preschool age through grade two, and grades three and up. The themes are used to unite the literature presented into a memorable whole, and to help with lesson planning. Programs for the grade two and under include books, films, fingerplays, dramatics, puppets, and crafts, and: last for 30 minutes. Programs for grade three and up run from 30 minutes to an hour and include booktalks, films, guest speakers, creative writing, drama, and art. Also included in this manual a::e guidelines and resources for providing services to children with hearing disabilities; clip art; lists of outside resources including outside speakers and music, miscellaneous, and environmental resources; puzzles, drawings, handouts, and giveaways; and guidelines and sample materials to assist librarians in organizing a reading program. -

Volum© On©^ Numb©R Six

Volum© On©^ Numb©r Six BEHIND BARS: Women who break with traditional roles often end up in prison, and sometimes life's easier there than on the streets or in the home. Page by Deena Rasky 10. When you gci your monthly Beil Canada bill in the mail, you'll notice thaï the envelope cheerfully informs you the com• pany is celebrating its 100th birthday. The image Bell would like to convey to its customers is of wise old Alexander Graham Bell creating his invention, of smiling operators and of phone users marvelling over modern technology. MILKING THE THIRD WORLD: In• But instead of celebrating, 7,400 fant bottle-feeding formula is big operators and dining service attendants ac• business, especially in Third World ross Canada were on strike for iwo months countries, where it's pushed as the without a contract. 100% of the Bell "modern way". Protesters strike back workers have been exploited, 95% are with the Nestlé Boycott. Page 6. women. The top wage an operator in the major cities such as Toronto and Montreal BASEMENT VIOLENCE: Kate Miliett couid expect to make, regardless of how talks about society's violence towards long she'd been working was $194.29 week• women, women's violence to each other, ly. The cafeteria workers made only eigh• and hei recer.c book The Baseme.it, ?u teen cenfs more than the Quebec minimum the Univeïsily of British Columbia Pc.£f; wage. Most of fhese workers are new Cana• dians and a considerable number have been working part time at an even lower wage. -

Summer Youth Program Manual Volume 2: Set-Up

Summer Youth Program Manual Volume 2: Set-Up Meg Coward Lincoln and Roxbury, Massachusetts Copyright © 2004 by The Food Project, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, The Food Project, Inc., except where permitted by law. (mailing address) The Food Project, Inc. P.O. Box 705 Lincoln, MA 01773 781-259-8621 (urban office) The Food Project, Inc. 555 Dudley Street Dorchester, MA 02124 617-442-1322 www.thefoodproject.org e-mail: [email protected] First Edition, 2004 Designer: Pertula George Editor: Helen Willett Photographs: Greig Cranna, John Walker, Ellen Bullock and Food Project Staff Cover Photograph: Veronique Latimer Cover Design: J.A. James Our Vision: Creating personal and social change through sustainable agriculture. Our Mission: The Food Project’s mission is to create a thoughtful and productive community of youth and adults from diverse backgrounds who work together to build a sustainable food system.Our community produces healthy food for residents of the city and suburbs, provides youth leadership opportunities, and inspires and supports others to create change in their own communities. Foreword The Food Project started in 1991 in Lincoln, Massachusetts, on two acres of farmland. It was a small, noisy, and energetic community of young people from very different races and backgrounds, working side by side with adults growing and distributing food to the hungry. In the process of growing food together, we created a community that bridges the city and suburb, is respectful and productive, and models hope and purpose. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

German Minnesang, Although in the English Language, to Allow It to Be Judged in This Kingdom A&S Competition

I follow her banner Unlike a helpless sparrow that is the swift hawk’s prey Just like a hunter’s arrow once aimed will kill the jay So she will be my destiny to conquer her my finest deed She forced me almost to retreat with beauty, grace and chastity My life was vain and hollow and frequently I went astray No better banner I can follow than hers, wherever is the way. Is she at least aware of me? from places far away I heed I am a grain in fields of wheat a drop of water in the sea. I suffer from a dreadful sorrow how often did I quietly pray That there will be no more tomorrow so that my pain shall go away. My bended neck just feels her knee crouched in the dust beneath her feet Deliverance, which I so dearly need she never will award to me. 1 Nîht ein baner ich bezzer volgen mac Middle-High German version Niht swie diu spaz sô klein waz ist der snel valken bejac alsô swie der bogenzein ûf den edel valken zil mac sô si wirt sîn mîne schône minne ir eroberigen daz ist mîne bürde mîne torheit wart gevalle vor ir burc aber dur ir tugenden unde staetem sinne Was sô verdriezlich mîne welte verloufen vome wege manige tac mîne sunnenschîn unde schône helde nîht ein baner ich bezzer volgen mac ûzem vremde lant kumt der gruoze mîn wie sol si mich erkennen enmitten vome kornat blôz ein halm enmitten vome mer ein kleine tröpfelîn Ich bin volleclîche gar von sorgen swie oft mac ich wol mahtlôs sinnen daz ie niemer ist ein anders morgen alsô mîne endelôs riuwe gât von hinnen der nûwe vrôdenreich wol doln ir knie in drec die stolzecheit kumt ze ligen die gunst diu ich sô tuon beger mîner armen minne gift si nimmer nie 2 Summary Name: Falko von der Weser Group: An Dun Theine This entry is a poem I wrote in the style of the high medieval German Minnelieder (Minnesongs) like those found in the “Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift”, also known as Codex Manesse (The Great Heidelberg Songbook) and the “Weingartner Liederhandschrift” (The Konstanz-Weingarten Songbook). -

Readers of the Round Table: the 1998 Joint Kentucky Arizona Reading Program

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 604 IR 057 328 TITLE Readers of the Round Table: The 1998 Joint Kentucky Arizona Reading Program. INSTITUTION Kentucky State Dept. for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort.; Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 357p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Tests/Questionnaires (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Childrens Libraries; Childrens Literature; *Creative Activities; Elementary Secondary Education; Enrichment Activities; *Library Services; *Medieval History; Parent Participation; Preschool Education; Program Guides; *Public Libraries; Questionnaires; *Reading Programs; Resource Materials; *Summer Programs; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Arizona; Kentucky ABSTRACT Intended to encourage children of all ages to read over the summer, this manual presents library-based programs, crafts, displays, and events with a medieval theme. The chapters of the manual are: (1) Introductory Materials;(2) Goals, Objectives and Evaluation;(3) Getting Started;(4) Common Program Structures;(5) Planning Timeline;(6) Publicity and Promotion;(7) Awards and Incentives;(8) Parents/Family Involvement; (9) Programs for Preschoolers, including display ideas, flannel board stories, origami, puzzle stories, songs, crafts, activities, plays, crafts, recipes, medieval clip art, and a preschool bibliography; (10) Programs for School Age Children, including entertainment programs, songs, activities, and a school age bibliography;(11) Programs for Young Adults, including activities, a medieval menu, and a young adult bibliography;(12) Special Needs; and (13) Resources, including people, companies, and materials. A master copy of a reading log and reading program evaluation form are included.(AEF) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Song List by Artist

Song List by Artist Artist Song Name 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT EAT FOR TWO WHAT'S THE MATTER HERE 10CC RUBBER BULLETS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 ANYWHERE [FEAT LIL'Z] CUPID PEACHES AND CREAM 112 FEAT SUPER CAT NA NA NA NA 112 FEAT. BEANIE SIGEL,LUDACRIS DANCE WITH ME/PEACHES AND CREAM 12TH MAN MARVELLOUS [FEAT MCG HAMMER] 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 2 BROTHERS ON THE 4TH FLOOR COME TAKE MY HAND NEVER ALONE 2 COW BOYS EVERYBODY GONFI GONE 2 HEADS OUT OF THE CITY 2 LIVE CREW LING ME SO HORNY WIGGLE IT 2 PAC ALL ABOUT U BRENDA’S GOT A BABY Page 1 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name HEARTZ OF MEN HOW LONG WILL THEY MOURN TO ME? I AIN’T MAD AT CHA PICTURE ME ROLLIN’ TO LIVE & DIE IN L.A. TOSS IT UP TROUBLESOME 96’ 2 UNLIMITED LET THE BEAT CONTROL YOUR BODY LETS GET READY TO RUMBLE REMIX NO LIMIT TRIBAL DANCE 2PAC DO FOR LOVE HOW DO YOU WANT IT KEEP YA HEAD UP OLD SCHOOL SMILE [AND SCARFACE] THUGZ MANSION 3 AMIGOS 25 MILES 2001 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT WHEN IM GONE 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO LOVE CRAZY EXTENDED VOCAL MIX 30 SECONDS TO MARS FROM YESTERDAY 33HZ (HONEY PLEASER/BASS TONE) 38 SPECIAL BACK TO PARADISE BACK WHERE YOU BELONG Page 2 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN, THE CAUGHT UP IN YOU HOLD ON LOOSELY IF I'D BEEN THE ONE LIKE NO OTHER NIGHT LOVE DON'T COME EASY SECOND CHANCE TEACHER TEACHER YOU KEEP RUNNIN' AWAY 4 STRINGS TAKE ME AWAY 88 4:00 PM SUKIYAKI 411 DUMB ON MY KNEES [FEAT GHOSTFACE KILLAH] 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS [FEAT NATE DOGG] A BALTIMORE LOVE THING BUILD YOU UP CANDY SHOP (INSTRUMENTAL) CANDY SHOP (VIDEO) CANDY SHOP [FEAT OLIVIA] GET IN MY CAR GOD GAVE ME STYLE GUNZ COME OUT I DON’T NEED ‘EM I’M SUPPOSED TO DIE TONIGHT IF I CAN’T IN DA CLUB IN MY HOOD JUST A LIL BIT MY TOY SOLDIER ON FIRE Page 3 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name OUTTA CONTROL PIGGY BANK PLACES TO GO POSITION OF POWER RYDER MUSIC SKI MASK WAY SO AMAZING THIS IS 50 WANKSTA 50 CENT FEAT. -

Bushwhacking Through Narcissism: the Making of a Jungian Analyst

Bushwhacking Through Narcissism: The Making of a Jungian Analyst by John Ryan Haule Copyright © 1993 All Rights Reserved http://www.jrhaule.net/bushwhack.html One Mara Probably every analyst can cite a small number of analysands whose work has taught him or her what analysis is all about. For regardless of the books we have read and the number of years spent in training, it is only when we face another psyche entirely on our own that the realities of our profession begin to dawn on us. The dialogue between two souls is a dissolving experience. The extent to which we allow ourselves into it corresponds to our ability to tolerate fragmentation and confusion. Jung often referred to this experience as "the soup," where onions, potatoes, carrots, herbs, and meat, mingle their flavors to produce a delectable and nourishing broth. In an analysis of this sort, both psyches are softened and give up some of their essence to the process. It is widely known that this can be a terrifying experience for an analysand with a weak sense of self. But the analyst is supposed to have been analyzed and to have developed thereby a real confidence in the ego-self axis and furthermore to be "contained" by a flexible and coherent familiarity with the models and theory of analysis. Ideally this conception suffices. The analysand meets our expectations, and we can rely on the customary maps of soulscape we have learned from our training and general life experience. If we have to depart from familiar paths, the compass we forged in our own analysis keeps us oriented. -

Oroonoko Or the Royal Slave a True History

Aphra Behn O R O O N O K O A True History Contents The Epistle Dedicatory Oroonoko Or The Royal Slave A True History Follow Penguin APHRA BEHN Born c. 1640, Canterbury, England Died 1689, London, England Taken from Oroonoko, edited by Janet Todd and published in Penguin Classics in 2003. APHRA BEHN IN PENGUIN CLASSICS Oroonoko, The Rover and Other Works Oroonoko The Epistle Dedicatory To the Right Honourable the Lord Maitland. My Lord, Since the world is grown so nice and critical upon dedications, and will needs be judging the book by the wit of the patron, we ought, with a great deal of circumspection, to choose a person against whom there can be no exception; and whose wit and worth truly merits all that one is capable of saying upon that occasion. The most part of dedications are charged with flattery; and if the world knows a man has some vices, they will not allow one to speak of his virtues. This, my Lord, is for want of thinking rightly; if men would consider with reason, they would have another sort of opinion and esteem of dedications, and would believe almost every great man has enough to make him worthy of all that can be said of him there. My Lord, a picture-drawer, when he intends to make a good picture, essays the face many ways and in many lights before he begins; that he may choose, from the several turns of it, which is most agreeable, and gives it the best grace; and if there be a scar, an ungrateful mole, or any little defect, they leave it out, and yet make the picture extremely like. -

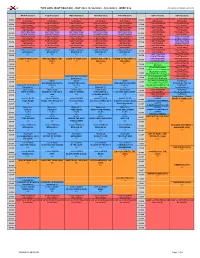

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO