Byrd Draft 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garlactic Arkestral Orchestra

Garlactic Arkestral Orchestra Proudly present ALL ITALIAN EARLY MUSIC Cover image from: http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/gris/music/violin- guitar/gris.violin-guitar.jpg Garlactic Arkestral Orchestra Peter Schrödingerus, Music Director John P. Lagrange, Conductor Emeritus Wilhelm Potatoman Conducting Monteverdi Toccata and Prologue from L’Orfeo Corelli Concerto Grosso Op. 6 No. 8 Palestrina Tu es Petrus Kyrie from Missa Tu es Petrus DuFay Nuper rosarum flores Gabrieli Sonata pian e forte a 8 Strozzi Lagrime mie Midori Buffety, soprano Imagine that we ignore any music related to Claudio Monteverdi was about forty years old Italy from the western music history, how much will when his first opera, L’Orfeo, had its premiere in be lost? Perhaps it is easier to ask how much will be Mantua in 1607 to the members of Accademia degli left. The Marriage of Figaro is sung in Italian (also for Invaghiti. By the letter that Francesco Gonzaga, the Don Giovanni and Cosi Fan Tutte). Vivaldi’s Four dedicatee of the opera, sent to his brother about the Seasons will be gone. Can you imagine a classical performance of Feburary 24, we might conclude that music world without Four Seasons? Certainly, Italy the premiere was given in a small room in an has been playing a major role in cultivating the apartment owned by the Duchess of Ferrara— musical tradition since the Medieval. Our standard Margherita. However, in the preface of the score musical notation, though always gradually changing edited by Denis Stevens, the editor pointed out that the with the new inventions in the twentieth century, is letter hinted a little bit about the actual premiere date. -

P Tifical HIGH MASS

PTIFICa LHIGHMASS in tHe o rdinariate use of the ro man rite for tHe FEASTof SAINT G GRY On the Occasion of this Community’s Fourth Feast of Title and Dedication And the First Episcopal Visitation of our Bishop His Excellency Steven J. Lopes Friday, September Second at Seven-Thirty in the Evening at Saint Andrew’s Parish, Billerica Massachusetts Saint Gregory the Great Church A Community of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter Memoranda. His Excellency Steven J. Lopes celebrant The Very Reverend Fr. Timothy Perkins concelebrant The Reverend Fr. Jürgen W.V. Liias concelebrant Deacon Edward Giordano deacon Deacon Charles Hall subdeacon Mr. David Allen master of ceremonies Mr. Raymond Chagnon master of ceremonies Mr. Kevin McDermott verger Mr. Ryan Hawkes thurifer Mr. Richard Piwowarski crucifer Mr. Joe Cooley acolyte Mr. Steven Hardy acolyte Mr. Peter Glendinning acolyte Mr. Alastair-Ian Means acolyte Mr. Thomas O’Neill acolyte Mr. Joshua Pulliam acolyte Mr. Kevin Roy acolyte Mrs. Elise Sweet reader Mr. Joseph McLellan intercessor Mr. & Mrs. John Covert processors chappel Ms. Jessica Petrus treble Ms. Carey Shunskis treble Ms. Stephanie Scogna mean Mr. Jason McStoots tenor Mr. Marc DeMille baritone Mr. Jacob Cooper bass Mr. Richard Chonak clerk Mr. Michael Olbash choir director & precentor Mr. Michael Zadig music director & organist 3 .f The Feast of Saint Gregory the Great (vigil) Pontifical High Mass in the Ordinariate Use of the Roman Rite Friday 2. September 2016 .f 7:30 in the Evening organ prelude Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr (bwv 662) — Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Processional Hymn ¶Stand. -

The Department of Music of the University of Alberta Presents The

The Department of Music of The University of Alberta presents The Madrigal Singers LEONARD RATZLAFF, Conductor with Norman Nelson, violin Michael Beert, cello Lawrence Fisher, violin Jan Urke, bass Michael Bowie, viola Brian Jones, percussion Sunday, November 4, 1984 at 8:00 p.m. Convocation Hall, Old Arts Building Tu es Petrus (c. 1572) Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594) Missa Tu es Petrus (1601) Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594) Kyrie Sanctus - Benedictus - Osanna Agnus Dei I Agnus Dei II Denise Lemke, Janet Halsall, soprano; Edette Gagne, alto; Ed Green, tenor This is the record of John (c. 1618) Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625) Edette Gagne, alto Elegischer Gesang, Op. 118 (1814) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Sancta Maria, K. 273 (1777) Wolfgang Amedeus Mozart (1756-1791) INTERMISSION cik. -16 657 Psalm 13: Herr, wie lange, Op. 27 (1859) Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11 (1865) Gabriel Faure (1845-1924) (accomp. arr. L. Fisher) Music for Mouths, Marimba, Mbira and Roto-Toms (1973) Malcolm Forsyth (b.1936) THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA MADRIGAL SINGERS Soprano Alto Heather Davidson Edette Gagne Janet Halsall Joy-Anne Murphy Jane Hartling Karla Wagner Denise Lemke Michelle Wiart Kathleen Neudorf Shauna Young Marusia Prokopiw Tenor Bass Ian Armstrong Jon Eriksson Ed Green Laurier Fagnan Glen Halls Quinton Hackman Wayne Lemire Paul Mitchinson David Zacharko TEXTS AND TRANSLATIONS Tu es Petrus Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petram Thou art Peter, and on this rock edificabo ecclesiam meam, et portae I shall build my church, and all the inferi non prevalebunt adversus eam, gates of hell shall not prevail against et tibi dabo claves regni coelorum. -

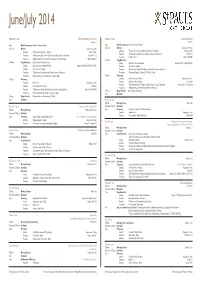

Service Schedule Beginning 22 June BASIC SHEET.Qxd

June/July 2014 Sunday 22nd June The First Sunday after Trinity Sunday 29th June Peter the Apostle Cantoris 1 Decani 1 8 am Holy Communion Book of Common Prayer 8 am Holy Communion Book of Common Prayer 10.15 am Mattins Responses Smith 10.15 am Mattins Responses Moore Canticles Te Deum and Jubilate in F Ireland Venite Monk Canticles Te Deum (First Service); Jubilate (Short Service) Weelkes Venite Ayrton Preacher The Reverend Jonathan Coore, Minor Canon and Succentor Psalm 113 Preacher The Reverend Canon Mark Oakley, Chancellor, Canon in Residence Psalm 49. 1-12 Voluntary A Fancie Byrd Hymns 468, 206 Voluntary Allegretto & Andante espressivo from Sonata in G (Op. 28) Elgar Hymns 346, 354 11.30 am Sung Eucharist 11.30 am Sung Eucharist City of London Festival Service Setting Missa Tu es Petrus Palestrina Hymns SP 217 (i), 464, 478, 272 Setting Mass in G minor Vaughan Williams Hymns 398 (395), SP 203, 437, 205 Anthem Tu es Petrus Duruflé Anthem Come my soul Howells Preacher The Reverend Canon Mark Oakley, Chancellor, Canon in Residence Preacher The Reverend Sarah Eynstone, Minor Canon and Chaplain Voluntary Prelude and Fugue in E minor (BWV 548) J. S. Bach Voluntary Allegro maestoso from Sonata in G (Op. 28) Elgar 3.15 pm Evensong 3.15 pm Evensong Canticles Chichester Service Walton Responses Moore Canticles Murrill in E Responses Smith Anthem Hymn to St Peter Britten Psalm 138 Preacher The Reverend Paul Dominiak, Chaplain, Trinity College, Cambridge Hymns 426, 419, 172 (443) Anthem The Evening Watch Holst Psalm 46 Voluntary Alléluia final from Livre du Saint Sacrement Messiaen Preacher The Reverend Richard Bastable, Vicar, St Luke’s, Uxbridge Road Hymns 393, 298, 360 4.45 pm Organ Recital Julian Bewig (Germany) Voluntary Presto (comodo) from Sonata in G (Op. -

Vienna « Singakademie » – Concerts Including Choral Works of Anton Bruckner (1888-2015)

Vienna « Singakademie » – Concerts including choral works of Anton Bruckner (1888-2015) Source : https://www.wienersingakademie.at/de/konzertarchiv/?archiv=composer&id=93 10 December 1888 « Großer-Musikvereins-Saal » , Vienna : Max von Weinzierl conducts the Vienna « Singakademie » Mixed-Choir. Soloists : Caroline Wogrincz (Soprano) , Josef Lamberg (Piano) . Johannes Brahms : « Fragen. Sehr lebhaft und rasch » (Asking) , Song in C major for women's choir, Opus 44, No. 4 (1859-1860) . Johannes Brahms : « Minnelied » (Song of Love) , Song in E major for women's choir, Opus 44, No. 1 (1859-1860) . Wilhelm Friedemann Bach : Chorus « Lasset uns ablegen die Werke der Finsternis » (F. 80) . Anton Bruckner : « Ave Maria » No. 2 ; Marian hymn in F major for 7-voice mixed unaccompanied choir (SAATTBB) (WAB 6) (1861) . Laurentius Lemlin : « Der Gutzgauch auf dem Zaune saß » , Folk-song for unaccompanied voices (1540) . Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina : « Missa Tu es Petrus » , Parody Mass for 6 mixed-voices (SSATBB) (IGP 110) . Carl Wilhelm Schauseil : « Mir ist ein schön’s braun’s Mägdelein » , folk-song. Franz Schubert : « Mirjams Siegesgesang » , Opus 136 (D. 942) . 13 May 1891 « Minoriten-Kirche » , Vienna. Max von Weinzierl conducts the Vienna « Singakademie » Mixed-Choir. Soloists : Sofie Chotek (Soprano) , Carl Führich (Organ) . Johann Sebastian Bach : « Welt, ade ! ich bin dein müde » (World, farewell ! I am weary of thee) , Chorale in B-flat major for 5-part mixed-choir (SSATB) and orchestra (BWV 27/6) (1726) . Anton Bruckner : « Ave Maria » No. 2 ; Marian hymn in F major for 7-voice mixed unaccompanied choir (SAATTBB) (WAB 6) (1861) . Hermannus Contractus (Herman the Cripple or Herman of Reichenau) : « Salve Regina » harmonized by Professor Franz Krenn. -

Summer 2010 Volume 137, Number 2

SACRED MUSIC Summer 2010 Volume 137, Number 2 EDITORIAL The Languages of the Liturgy | William Mahrt 3 ARTICLES Cantus Universalis: A Glimpse at the Supra-Cultural Value of Gregorian Chant | Gabriel Law 7 The Carol and Its Context in Twentieth Century England | Sean Vogt 13 The Gradual and the Responsorial Psalm | William Mahrt 20 REPERTORY The Alleluia Veni Sancte Spiritus for Pentecost | Ted Krasnicki 33 An English Chant Mass 37 COMMENTARY The New Translation: A Guide for the Perplexed | Fr. Christopher Smith 39 Shared Responsibilities| Mary Jane Ballou 41 The Musical Hope of the New Missal| Jeffrey Tucker 42 REVIEW Gregorian Chant by David Hiley| Jeffrey Tucker 50 A Recreation of an Obrecht Mass| Jeffrey Tucker 53 NEWS Muscia Sacra Florida Conference 55 Pontifical Solemn High Mass in Washington 56 Ward Method Courses: Summer 2010 58 SACRED MUSIC Formed as a continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of Publication: 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, VA 23233. E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.musicasacra.com Editor: William Mahrt Managing Editor: Jeffrey Tucker Associate Editor: David Sullivan Editor-at-Large: Kurt Poterack Typesetting: Judy Thommesen, with special assistance from Richard Rice Membership and Circulation: 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, VA 23233 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President: William Mahrt Vice-President: Horst Buchholz Secretary: Janet Gorbitz Treasurer: William Stoops Chaplain: Rev. -

Westminster Cathedral Choir Discography

Westminster Cathedral Choir Discography Palestrina: Missa Tu es Petrus & Missa Te Deum Laudamus Westminster Cathedral Choir, Martin Baker (conductor) The celebrated Choir of Westminster Cathedral goes back to its roots with this recording of some of the towering masterpieces of Renaissance polyphony — a genre which the choir has made its own through the ritual of daily liturgical performance. Recent reviews have declared the choir to be at the peak of its powers, and this disc is an important celebration of a great musical tradition. From the vaults of Westminster Cathedral Chant and polyphony from Advent to Christmas and the Epiphany and Presentation of our Lord A century ago, Richard Runciman Terry re-introduced the wonders of the Renaissance into liturgical polyphony and placedWestminster Cathedral Choir at the pinnacle of the art. “Splendid singing illuminates these works from the vaults of Westminster … Throughout, the choral singing under Martin Baker’s direction glows resplendently, while still retaining its celebrated ‘continental’ edge.” Gramophone “Impressive organ improvisations from Martin Baker complete a richly satisfying recording.” The Observer Victoria: Missa Gaudeamus A liturgical sequence for the Feast of the Assumption; organ music by Girolamo Frescobaldi A recording from Westminster Cathedral features the gentlemen of their choir in a fascinating programme which brings to life the musical and liturgical traditions of this foundation. “The Lay Clerks make a gloriously full-bodied sound with plenty of contrast and colour -

Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina Missa »Tu Es Petrus« Mp3, Flac, Wma

Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina Missa »Tu Es Petrus« mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Missa »Tu Es Petrus« Country: Germany Style: Renaissance MP3 version RAR size: 1352 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1429 mb WMA version RAR size: 1139 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 914 Other Formats: RA TTA DTS MOD MP2 AC3 WAV Tracklist 1 Laudate Dominum Omnnes Gentes 2:45 2 Motette »Tu Es Petrus« 6:59 Missa »Tu Es Petrus« 3 Kyrie 3:59 4 Gloria 4:24 5 Credo 7:12 6 Sanctus 2:08 7 Benedictus 2:51 8 Agnus Dei 3:51 - 9 Motette »Dum Complerentur« 5:37 Missa »Dum Complerentur« 10 Kyrie 4:10 11 Gloria 5:39 12 Credo 8:25 13 Sanctus 3:11 14 Benedictus 2:37 15 Agnus Dei 4:03 - 16 Motette »Jubilate Deo« 3:56 Credits Choir – Regensburger Domchor Chorus Master – Hans Schrems (tracks: 2 to 15), Theobald Schrems (tracks: 1, 16) Composed By – Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 028944511529 Related Music albums to Missa »Tu Es Petrus« by Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina Classical Mozart, Peter Neumann - Messen / Masses K. 49 • 65 • 140 • K. 220 "Spatzen-Messe" Classical Johannes Ockeghem · Jacob Obrecht - Cappella Lipsiensis · Dietrich Knothe - Missa Mi-Mi / Missa Sub Tuum Presidium Confugimus Classical Fauré - Choir Of King's College / Willcocks / New Philharmonia Orchestra, Palestrina - Requiem /Pavane / Missa Papae Marcelli Classical Jan Dismas Zelenka : Collegium 1704, Collegium Vocale 1704, Václav Luks - Missa Votiva ZWV 18 Classical Palestrina – Sistine Chapel Choir, Massimo Palombella - Missa Papae Marcelli | Motets Classical Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Mozart Masses Classical Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina - The Sixteen, Harry Christophers - Ave Maria / Stabat Mater Dolorosa / Missa Papae Marcelli / Miserere / Crucifixus Classical Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina, Pio Fernandez, Coro Polifonico Prenestino Giovanni Pierluigi - Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina Classical Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Missa Brevis Classical Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Regensburger Domspatzen, Theobald Schrems - Stabat Mater (Ausschnitte). -

GIULIA GALASSO a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of Birmingham City University for the Degree Of

THE MASS COLLECTION OCTO MISSAE (1663) BY FRANCESCO FOGGIA (1603-1688): AN ANALYTICAL STUDY AND CRITICAL EDITION GIULIA GALASSO A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Birmingham City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, The Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University ABSTRACT Francesco Foggia (1603-1688) was one of the most prominent maestri di cappella of seventeenth-century Rome and an important mass composer. Historically, he has been regarded as one of the last heirs of Palestrina, largely due to the writings of Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni (1657-1743) and Giovanni Battista Martini (1706-1784). More recently, scholars have reassessed his style in his motets, psalms and oratorios. However, his mass style has received little rigorous scholarly attention. This is partly because of the scarcity of critical editions of his works. The present study presents critical editions of five of the masses from his Octo missae (Rome: Giacomo Fei, 1663). In conjunction with the three masses included in Stephen R. Miller‟s recent edition (2017), the entire volume is now available in full score. This enables an informed reassessment of Foggia‟s mass style. The present study analyses his use of features, such as time signatures, full choir and stile concertato, textures, thematic treatment and borrowing procedures. It compares Foggia‟s mass style with those of his predecessors, mainly Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c.1525-1594), Ruggero Giovannelli (c.1560-1625), near predecessor Gregorio Allegri (1582-1652) and contemporaries, Bonifatio Gratiani (1604/5-1664), Orazio Benevoli (1605-1672). -

Choral and Church Music

BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Mcnrg m. Sage 1891 9306 MUSIC Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V 6 The art of music :a comDrehensjv^^^ 3 1924 022 385 318 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385318 THE ART OF MUSIC v The Singing Angels AUdf piece Hg Hubert and Jan van Eyck The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia University Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Fast Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modern Music Society of New Yorlc In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC THE AET OP MUSIC: VOLUME SIX Choral and Church Music ROSSETTER GLEASON COLE, M.A. Introduction by FRANK DAMROSCH, Mus. Doc. Director Institute of Musical Art in the City of New York Conductor, Musical Art Society of New York, etc. NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Copyright, 1915, by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Eights Reserved] PREFATORY NOTE The field of choral and church music is so vast and the subject so inclusive that the author has felt the con- stant pressure of the necessity for sifting and abbrevi- ating and condensing the voluminous material at hand in order not to go far beyond the prescribed limits of this volume. -

L' Archivio Musicale Della Basilica Di San Giovanni in Laterano Catalogo

PUBBLICAZIONI DEGLI ARCHIVI DI STATO STRUMENTI CLIII ISTITUTO DI BIBLIOGRAFIA MUSICALE (I.BI.MUS) L’Archivio musicale della Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano Catalogo dei manoscritti e delle edizioni (secc. XVI-XX) a cura di GIANCARLO ROSTIROLLA Introduzione di WOLFGANG WITZENMANN II MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI DIREZIONE GENERALE PER GLI ARCHIVI 2002 DIREZIONE GENERALE PER GLI ARCHIVI SERVIZIO DOCUMENTAZIONE E PUBBLICAZIONI ARCHIVISTICHE Direttore generale per i beni archivistici: Salvatore Italia Direttore del servizio: Antonio Dentoni-Litta Comitato per le pubblicazioni: il direttore generale per gli archivi Salvatore Italia, presi- dente, Paola Carucci, Antonio Dentoni-Litta, Ferruccio Ferruzzi, Cosimo Damiano Fonseca, Guido Melis, Claudio Pavone, Leopoldo Puncuh, Isabella Ricci, Antonio Romiti, Isidoro Soffietti, Giuseppe Talamo, Lucia Fauci Moro, segretaria. Coordinamento e cura redazionale: Mauro Tosti-Croce Hanno collaborato alla cura del catalogo: Giovanni Insom, Luciano Luciani, Annapia Sciolari Meluzzi, Stefania Soldati, Sara Vallefuoco © 2002 Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali Direzione generale per gli archivi ISBN 88-7125-234-9 Vendita: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato-Libreria dello Stato Piazza Verdi 10, 00198 Roma Finito di stampare nel mese di Marzo 2003 a cura della Ediprint Service s.r.l. di Città di Castello (PG) con i tipi delle Grafiche PI.MA. SOMMARIO I Premessa VII Prefazione di Giancarlo Rostirolla IX Tabula graduatoria XV Il risultato di una collaborazione internazionale -

Giovanni Pierluigi Da Palestrina Missa Pro Defunctis & Motets Mp3, Flac

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Missa Pro Defunctis & Motets mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Missa Pro Defunctis & Motets Country: Germany Released: 1997 Style: Renaissance MP3 version RAR size: 1525 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1167 mb WMA version RAR size: 1800 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 974 Other Formats: AAC RA WAV MP4 AU MPC FLAC Tracklist 1 Gaude Gloriosa Missa Pro Defunctis 2 Requiem Aeternam 3 Kyrie 4 Offertorium 5 Sanctus 6 Agnus Dei 7 Salve Regina 8 Pange Lingua 9 O Bone Jesu Canticum Canticorum 10 Trahe Me 11 Nigra Sum, Sed Formosa 12 Surge, Propera 13 Surge, Amica Mea 14 Quam Pulchra Es 15 Veni, Dilecte Mi 16 Gaude, Barbara Notes ℗ 1994 Teldec Classics International GMBH © 1997 Teldec Classics International GMBH Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 706301859421 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Palestrina*, Chanticleer - Missa Palestrina*, D 106302 Pro Defunctis / Motets (CD, TELDEC D 106302 US 1994 Chanticleer Album, Club) Related Music albums to Missa Pro Defunctis & Motets by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Palestrina, The Tallis Scholars Directed By Peter Phillips - Palestrina Masses: Missa Benedicta Es Palestrina - King's College Choir, Cambridge • Philip Ledger - Missa Hodie Christus Natus Est & Six Motets Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Regensburger Domchor, Theobald Schrems - Missa Papae Marcello / 8 Motetten Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, De Labyrintho, Walter Testolin - Canticum Canticorum Palestrina - Tölzer Knabenchor • Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden - Missa Tu Es Petrus & Motetten Palestrina / Monteverdi - Missa "De Beata Virgine" / Sacrae Cantiunculae Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, The Tallis Scholars, Peter Philips - Missa Assumpta est Maria. Missa Sicut Lilium Josquin Des Prés - Missa Pange lingua.