Criminal Insurgency in the Americas and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests

Home Country of Origin Information Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) are research reports on country conditions. They are requested by IRB decision makers. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIR. Earlier RIR may be found on the European Country of Origin Information Network website. Please note that some RIR have attachments which are not electronically accessible here. To obtain a copy of an attachment, please e-mail us. Related Links • Advanced search help 15 August 2019 MEX106302.E Mexico: Drug cartels, including Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel (Cartel del Golfo), La Familia Michoacana, and the Beltrán Leyva Organization (BLO); activities and areas of operation; ability to track individuals within Mexico (2017-August 2019) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 1. Overview InSight Crime, a foundation that studies organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean (Insight Crime n.d.), indicates that Mexico’s larger drug cartels have become fragmented or "splintered" and have been replaced by "smaller, more volatile criminal groups that have taken up other violent activities" (InSight Crime 16 Jan. 2019). According to sources, Mexican law enforcement efforts to remove the leadership of criminal organizations has led to the emergence of new "smaller and often more violent" (BBC 27 Mar. 2018) criminal groups (Justice in Mexico 19 Mar. 2018, 25; BBC 27 Mar. 2018) or "fractur[ing]" and "significant instability" among the organizations (US 3 July 2018, 2). InSight Crime explains that these groups do not have "clear power structures," that alliances can change "quickly," and that they are difficult to track (InSight Crime 16 Jan. -

Aasen -- Constructing Narcoterrorism As Danger.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Constructing Narcoterrorism as Danger: Afghanistan and the Politics of Security and Representation Aasen, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Donald Aasen, 2019. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Constructing Narcoterrorism as Danger: Afghanistan and the Politics of Security and Representation Greg Aasen A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2019 1 Abstract Afghanistan has become a country synonymous with danger. Discourses of narcotics, terrorism, and narcoterrorism have come to define the country and the current conflict. However, despite the prevalence of these dangers globally, they are seldom treated as political representations. This project theorizes danger as a political representation by deconstructing and problematizing contemporary discourses of (narco)terrorism in Afghanistan. Despite the globalisation of these two discourses of danger, (narco)terrorism remains largely under-theorised, with the focus placed on how to overcome this problem rather than critically analysing it as a representation. The argument being made here is that (narco)terrorism is not some ‘new’ existential danger, but rather reflects the hegemonic and counterhegemonic use of danger to establish authority over the collective identity. -

Los Zetas and Proprietary Radio Network Development

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 9 Number 1 Volume 9, No. 1, Special Issue Spring 2016: Designing Danger: Complex Article 7 Engineering by Violent Non-State Actors Los Zetas and Proprietary Radio Network Development James Halverson START Center, University of Maryland, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 70-83 Recommended Citation Halverson, James. "Los Zetas and Proprietary Radio Network Development." Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 1 (2016) : 70-83. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.1.1505 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Los Zetas and Proprietary Radio Network Development Abstract The years from 2006 through 2011 were very active years for a number of Mexican drug trafficking organizations. However, the group that probably saw the most meteoric rise in this period, Los Zetas, had a unique and innovative tool at their disposal. It was during these years that the group constructed and utilized a proprietary encrypted radio network that grew to span from Texas to Guatemala through the Gulf States of Mexico and across much of the rest of the country. This network gave the group an operational edge. It also stood as a symbol of the latitude the group enjoyed across vast areas, as this extensive illicit infrastructure stood, in the face of the government and rival cartels, for six years. -

Southwest Border Gang Recognition

SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Sheriff Sigifredo Gonzalez, Jr. Zapata County, Texas Army National Guard Project April 30th, 2010 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 1 of 19 Pages SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Lecture Outline I. Summary Page 1 II. Kidnappings Page 6 III. Gangs Page 8 IV. Overview Page 19 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 2 of 19 Pages Summary The perpetual growth of gangs and active recruitment with the state of Texas, compounded by the continual influx of criminal illegal aliens crossing the Texas-Mexico border, threatens the security of all U.S. citizens. Furthermore, the established alliances between these prison and street gangs and various drug trafficking organizations pose a significant threat to the nation. Gangs now have access to a larger supply of narcotics, which will undoubtedly increase their influence over and presence in the drug trade, as well as increase the level of gang-related violence associated with illegal narcotics trafficking. Illegal alien smuggling has also become profitable for prison and other street gangs, and potentially may pose a major threat to national security. Multi-agency collaboration and networking—supplemented with modern technology, analytical resources, and gang intervention and prevention programs—will be critical in the ongoing efforts to curtail the violence associated with the numerous gangs now thriving in Texas and the nation.1 U.S.-based gang members are increasingly involved in cross-border criminal activities, particularly in areas of Texas and California along the U.S.—Mexico border. Much of this activity involves the trafficking of drugs and illegal aliens from Mexico into the United States and considerably adds to gang revenues. -

Narco-Terrorism: Could the Legislative and Prosecutorial Responses Threaten Our Civil Liberties?

Narco-Terrorism: Could the Legislative and Prosecutorial Responses Threaten Our Civil Liberties? John E. Thomas, Jr.* Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................ 1882 II. Narco-Terrorism ......................................................................... 1885 A. History: The Buildup to Current Legislation ...................... 1885 B. Four Cases Demonstrate the Status Quo .............................. 1888 1. United States v. Corredor-Ibague ................................. 1889 2. United States v. Jiménez-Naranjo ................................. 1890 3. United States v. Mohammed.......................................... 1891 4. United States v. Khan .................................................... 1892 III. Drug-Terror Nexus: Necessary? ................................................ 1893 A. The Case History Supports the Nexus ................................. 1894 B. The Textual History Complicates the Issue ......................... 1895 C. The Statutory History Exposes Congressional Error ............ 1898 IV. Conspiracy: Legitimate? ............................................................ 1904 A. RICO Provides an Analogy ................................................. 1906 B. Public Policy Determines the Proper Result ........................ 1909 V. Hypothetical Situations with a Less Forgiving Prosecutor ......... 1911 A. Terrorist Selling Drugs to Support Terror ............................ 1911 B. Drug Dealer Using Terror to Support Drug -

Transnational Cartels and Border Security”

STATEMENT OF PAUL E. KNIERIM DEPUTY CHIEF OF OPERATIONS OFFICE OF GLOBAL ENFORCEMENT DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON BORDER SECURITY AND IMMIGRATION UNITED STATES SENATE FOR A HEARING ENTITLED “NARCOS: TRANSNATIONAL CARTELS AND BORDER SECURITY” PRESENTED DECEMBER 12, 2018 Statement of Paul E. Knierim Deputy Chief of Operations, Office of Global Enforcement Drug Enforcement Administration Before the Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration United States Senate December 12, 2018 Mr. Chairman, Senator Cornyn, distinguished Members of the subcommittee – on behalf of Acting Drug Enforcement Administrator Uttam Dhillon and the men and women of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), thank you for holding this hearing on Mexican Cartels and Border Security and for allowing the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to share its views on this very important topic. It is an honor to be here to discuss an issue that is important to our country and its citizens, our system of justice, and about which I have dedicated my professional life and personally feel very strongly. I joined the DEA in 1991 as a Special Agent and was initially assigned to Denver, and it has been my privilege to enforce the Controlled Substances Act on behalf of the American people for over 27 years now. My perspective on Mexican Cartels is informed by my years of experience as a Special Agent in the trenches, as a Supervisor in Miami, as an Assistant Special Agent in Charge in Dallas to the position of Assistant Regional Director for the North and Central America Region, and now as the Deputy Chief of Operations for DEA. -

Mexico: the Presence and Structure of Los Zetas and Their Activities Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help 5 March 2010 MEX103396.FE Mexico: The presence and structure of Los Zetas and their activities Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa According to an article published by Cable News Network (CNN), Los Zetas have existed since the 1990s (6 Aug. 2009). More specifically, the group was founded by commandos (CNN 6 Aug. 2009; NPR 2 Oct. 2009) or members of the special forces who deserted from the Mexican army (Agencia EFE 30 Jan. 2010; ISN 11 Mar. 2009). According to the United States (US) Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Los Zetas have adopted a business-style structure, which includes holding regular meetings (CNN 6 Aug. 2009). According to a DEA official’s statements that were published in an article by the International Relations and Security Network (ISN), “their willingness to engage in firefights” separates Los Zetas from all other criminal groups in Mexico (ISN 11 Mar. 2009). According to an article published by CNN in August 2009, the US government has stated that Los Zetas is “the most technologically advanced, sophisticated and dangerous cartel operating in Mexico” (6 Aug. 2009). National Public Radio (NPR) of the US indicates that the DEA considers Los Zetas to be “the most dangerous drug-trafficking organization in Mexico” and that its members are “the most feared” criminals in the country (NPR 2 Oct. 2009). An article published in a daily newspaper of Quito (Ecuador), El Comercio, describes Los Zetas as [translation] “the most violent” organization because it executes and kidnaps its enemies (1 Feb. -

Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations

Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) Albert De Amicis, MPPM, (MPIA, 2010) University of Pittsburgh Graduate School for Public and International Affairs Masters of Public and International Affairs Capstone Final Paper November 27, 2010 March 12, 2011, (Updated) Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) ii Table of Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................iv I. Introduction..........................................................................................................1 Los Zetas.......................................................................................................1 La Familia Michoacana.................................................................................3 II. Leadership...........................................................................................................7 Los Zetas........................................................................................................7 La Familia Michoacana..................................................................................8 III. Structure..............................................................................................................9 Los Zetas.........................................................................................................9 La Familia Michoacana.................................................................................10 IV. Force Structure................................................................................................. -

June 1994 150492- U.S

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I \\I (j) ~ o lC) Guiding Philosophies for Probation in the 21st Century ........... " Richard D. Sluder Allen D. Supp Denny C. Langston Identifying and Supervising Offenders Affiliated With Community Threat Groups .................................................. Victor A. Casillas Community Service: A Good Idea That Works ........................ Richard J. Maher Community-Based Drug Treatment in the Federal Bureau of Prisons ................................ , ....................... Sharon D. Stewart The Patch: ANew Alternative for Drug Testing in the Criminal Justice System ..................................................... James D. Baer Jon Booher Fines and Restitution Orders: Probationers' Perceptions ............ G. Frederick Allen Harvey Treger What Do Offenders Say About Supervision and Going Straight? ........ " Julie Leibrich Golden Years Behind Bars: Special Programs and Facilities for Elderly Inmates................................................. Ronald H. Aday Improving the Educational Skills of Jail Inmates: Preliminary Program Findings ................................•.......... Richard A. Tewksbury Gennaro F. Vito "Up to Speed"-Results of a Multisite Study of Boot Camp Prisons ................................................... Doris Layton MacKenzie "Looking at the Law"-Recent Cases on Probation and Supervised Release ............................................. David N. Adair, Jr. JUNE 1994 150492- U.S. Department of Justice 150501 National -

History of Gangs in the United States

1 ❖ History of Gangs in the United States Introduction A widely respected chronicler of British crime, Luke Pike (1873), reported the first active gangs in Western civilization. While Pike documented the existence of gangs of highway robbers in England during the 17th century, it does not appear that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious street gangs. Later in the 1600s, London was “terrorized by a series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys [and they] fought pitched battles among themselves dressed with colored ribbons to distinguish the different factions” (Pearson, 1983, p. 188). According to Sante (1991), the history of street gangs in the United States began with their emer- gence on the East Coast around 1783, as the American Revolution ended. These gangs emerged in rapidly growing eastern U.S. cities, out of the conditions created in large part by multiple waves of large-scale immigration and urban overcrowding. This chapter examines the emergence of gang activity in four major U.S. regions, as classified by the U.S. Census Bureau: the Northeast, Midwest, West, and South. The purpose of this regional focus is to develop a better understanding of the origins of gang activity and to examine regional migration and cultural influences on gangs themselves. Unlike the South, in the Northeast, Midwest, and West regions, major phases characterize gang emergence. Table 1.1 displays these phases. 1 2 ❖ GANGS IN AMERICA’S COMMUNITIES Table 1.1 Key Timelines in U.S. Street Gang History Northeast Region (mainly New York City) First period: 1783–1850s · The first ganglike groups emerged immediately after the American Revolution ended, in 1783, among the White European immigrants (mainly English, Germans, and Irish). -

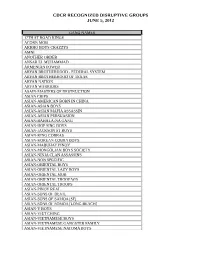

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

The Changing Social Organization of Prison Protection Markets: When Prisoners Choose to Organize Horizontally Rather Than Vertically

Trends Organ Crim https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-018-9332-0 The changing social organization of prison protection markets: when prisoners choose to organize horizontally rather than vertically R. V. Gundur1 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract This article revisits the framework which Buentello et al. (Prison J 71(2): 3– 14, 1991) created to describe the development of inmate solidarity groups into prison gangs in the Texas Department of Corrections. Interviews with current and former prison gang members in Texas, Arizona, and Illinois augment the current published literature on prison gangs in California. This article argues that the responses which prison administrations make to prisoners’ social orders are not static and have, in some cases, caused vertically configured groups to evolve into horizontally configured groups. These structural changes in prison gangs affect the gangs’ ability to affect control in the criminal underworld outside prison. Accordingly, although the challenges which prison administrations present to vertically developed social orders within prison may improve the administrations’ control within the prison walls, they may effectively decrease criminal-led social control on the street, leading to an increase in street-level violence. Keywords Prison gangs . Security threat groups . Social order. Protection rackets . Prisons . Organized crime Introduction To date, the majority of research undertaken, by academics and practitioners alike, on Bprison gangs,^ formally known as Bsecurity threat groups,^ focuses on vertically organized groups (Buentello et al. 1991; Fleisher and Decker 2001; Fong 1990; Orlando-Morningstar 1997; Pyrooz et al. 2011;Skarbek2014). The model of prison * R. V. Gundur [email protected] 1 Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK Trends Organ Crim gang development proposed by Buentello et al.