The Changing Social Organization of Prison Protection Markets: When Prisoners Choose to Organize Horizontally Rather Than Vertically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Situación De La Violencia Relacionada Con Las Drogas En México Del 2006 Al 2017 : ¿Es Un Conflicto Armado No Internacional

La situación de la violencia relacionada con las drogas en México del 2006 al 2017 : Titulo ¿es un conflicto armado no internacional? Arriaga Valenzuela, Luis - Prologuista; Guevara Bermúdez, José Antonio - Otra; Autor(es) Campo Esteta, Laura Martín del - Traductor/a; Universiteit Leiden, Grotius Centre for International Legal Studies - Autor/a; Guadalajara Lugar ITESO Editorial/Editor Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos 2019 Fecha Colección Tráfico de drogas; Drogas; Violencia; Carteles; México; Temas Libro Tipo de documento "http://biblioteca.clacso.org/Mexico/cip-iteso/20200713020717/03.pdf" URL Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Sin Derivadas CC BY-NC-ND Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.org Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.org La situación de la violencia relacionada con las drogas en México del 2006 al 2017: ¿es un conflicto armado no Internacional? La situación de la violencia relacionada con las drogas en México del 2006 al 2017: ¿es un conflicto armado no Internacional? COMISIÓN MEXIcaNA DE DEFENSA Y PROMOCIÓN DE LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS, A.C. CONSEJO DIRECTIVO COORDINacIÓN DE INCIDENCIA Ximena Andión Ibáñez Olga Guzmán Vergara Presidenta Coordinadora Alejandro Anaya Muñoz Jürgen Moritz Beatriz Solís Leere María Corina Muskus Toro Jacobo Dayán José Luis Caballero -

Ciudad Juarez: Mapping the Violence

Table of Contents How Juarez's Police, Politicians Picked Winners of Gang War ............................... 3 Sinaloa versus Juarez ................................................................................................................... 3 The 'Guarantors' ............................................................................................................................ 4 First Fissures, then a Rupture.................................................................................................... 4 Towards a New Equilibrium? ..................................................................................................... 6 Barrio Azteca Gang Poised for Leap into International Drug Trade ..................... 7 Flying 'Kites' and Expanding to the 'Free World' ................................................................. 7 Barrio Azteca’s Juarez Operation ............................................................................................. 8 The New Barrio Azteca ................................................................................................................ 9 Barrio Azteca’s Modus Operandi .............................................................................................. 9 Becoming International Distributors? ................................................................................. 10 Police Use Brute Force to Break Crime’s Hold on Juarez ........................................ 12 Case Study: Victor Ramon Longoria Carrillo ..................................................................... -

Southwest Border Gang Recognition

SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Sheriff Sigifredo Gonzalez, Jr. Zapata County, Texas Army National Guard Project April 30th, 2010 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 1 of 19 Pages SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Lecture Outline I. Summary Page 1 II. Kidnappings Page 6 III. Gangs Page 8 IV. Overview Page 19 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 2 of 19 Pages Summary The perpetual growth of gangs and active recruitment with the state of Texas, compounded by the continual influx of criminal illegal aliens crossing the Texas-Mexico border, threatens the security of all U.S. citizens. Furthermore, the established alliances between these prison and street gangs and various drug trafficking organizations pose a significant threat to the nation. Gangs now have access to a larger supply of narcotics, which will undoubtedly increase their influence over and presence in the drug trade, as well as increase the level of gang-related violence associated with illegal narcotics trafficking. Illegal alien smuggling has also become profitable for prison and other street gangs, and potentially may pose a major threat to national security. Multi-agency collaboration and networking—supplemented with modern technology, analytical resources, and gang intervention and prevention programs—will be critical in the ongoing efforts to curtail the violence associated with the numerous gangs now thriving in Texas and the nation.1 U.S.-based gang members are increasingly involved in cross-border criminal activities, particularly in areas of Texas and California along the U.S.—Mexico border. Much of this activity involves the trafficking of drugs and illegal aliens from Mexico into the United States and considerably adds to gang revenues. -

Heroin, and Marijuana Are Smuggled Into the State from Mexico for Distribution Within Texas Or for Eventual Transport to Drug Markets Throughout the Nation

ARCHIVED October 2003 Texas Drug Threat Assessment National Drug Intelligence Center 319 WASHINGTON STREET • 5TH FLOOR • JOHNSTOWN, PA 15901-1622 • (814) 532-4601 U.S. Department of Justice NDIC publications are available on the following web sites: ADNET http://ndicosa LEO home.leo.gov/lesig/ndic This document may contain dated information. RISS ndic.riss.net INTERNET www.usdoj.gov/ndic 092403 It has been made available to provide access to historical materials. ARCHIVED U.S. Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center Product No. 2003-S0387TX-001 October 2003 Texas Drug Threat Assessment National Drug Intelligence Center 319 Washington Street, 5th Floor Johnstown, PA 15901-1622 (814) 532-4601 This document may contain dated information. It has been made available to provide access to historical materials. ARCHIVED Preface This report is a strategic assessment that addresses the status and outlook of the drug threat to Texas. Analytical judgment determined the threat posed by each drug type or category, taking into account the most current quantitative and qualitative information on availability, demand, production or cultivation, transportation, and distribution, as well as the effects of a particular drug on abusers and society as a whole. While NDIC sought to incorporate the latest available information, a time lag often exists between collection and publication of data, particularly demand-related data sets. NDIC anticipates that this drug threat assessment will be useful to policymakers, law enforcement personnel, and treatment providers at the federal, state, and local levels because it draws upon a broad range of information sources to describe and analyze the drug threat to Texas. -

From Drug Wars to Criminal Insurgency: Mexican Cartels, Criminal Enclaves and Criminal Insurgency in Mexico and Central America

From Drug Wars to Criminal Insurgency: Mexican Cartels, Criminal Enclaves and Criminal Insurgency in Mexico and Central America. Implications for Global Security John P. Sullivan To cite this version: John P. Sullivan. From Drug Wars to Criminal Insurgency: Mexican Cartels, Criminal Enclaves and Criminal Insurgency in Mexico and Central America. Implications for Global Security. 2011. halshs-00694083 HAL Id: halshs-00694083 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00694083 Preprint submitted on 3 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. From Drug Wars to Criminal Insurgency: Mexican Cartels, Criminal Enclaves and Criminal Insurgency in Mexico and Central America. Implications for Global Security John P. Sullivan N°9 | april 2012 Transnational organized crime is a pressing global security issue. Mexico is currently embroiled in a pro- tracted drug war. Mexican drug cartels and allied gangs (actually poly-crime organizations) are currently chal- lenging states and sub-state polities (in Mexico, Gua- temala, El Salvador and beyond) to capitalize on lucra- tive illicit global economic markets. As a consequence of the exploitation of these global economic flows, the cartels are waging war on each other and state institu- tions to gain control of the illicit economy. -

Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations

Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) Albert De Amicis, MPPM, (MPIA, 2010) University of Pittsburgh Graduate School for Public and International Affairs Masters of Public and International Affairs Capstone Final Paper November 27, 2010 March 12, 2011, (Updated) Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) ii Table of Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................iv I. Introduction..........................................................................................................1 Los Zetas.......................................................................................................1 La Familia Michoacana.................................................................................3 II. Leadership...........................................................................................................7 Los Zetas........................................................................................................7 La Familia Michoacana..................................................................................8 III. Structure..............................................................................................................9 Los Zetas.........................................................................................................9 La Familia Michoacana.................................................................................10 IV. Force Structure................................................................................................. -

June 1994 150492- U.S

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I \\I (j) ~ o lC) Guiding Philosophies for Probation in the 21st Century ........... " Richard D. Sluder Allen D. Supp Denny C. Langston Identifying and Supervising Offenders Affiliated With Community Threat Groups .................................................. Victor A. Casillas Community Service: A Good Idea That Works ........................ Richard J. Maher Community-Based Drug Treatment in the Federal Bureau of Prisons ................................ , ....................... Sharon D. Stewart The Patch: ANew Alternative for Drug Testing in the Criminal Justice System ..................................................... James D. Baer Jon Booher Fines and Restitution Orders: Probationers' Perceptions ............ G. Frederick Allen Harvey Treger What Do Offenders Say About Supervision and Going Straight? ........ " Julie Leibrich Golden Years Behind Bars: Special Programs and Facilities for Elderly Inmates................................................. Ronald H. Aday Improving the Educational Skills of Jail Inmates: Preliminary Program Findings ................................•.......... Richard A. Tewksbury Gennaro F. Vito "Up to Speed"-Results of a Multisite Study of Boot Camp Prisons ................................................... Doris Layton MacKenzie "Looking at the Law"-Recent Cases on Probation and Supervised Release ............................................. David N. Adair, Jr. JUNE 1994 150492- U.S. Department of Justice 150501 National -

Southern New Mexico/ Texas Gang Update 2012 Edited by Robert J

BUSINESS NAME Southern New Mexico/ Texas Gang Update 2012 Edited by Robert J. Durán, Jason A. Campos, and Maria Bordt Volume 1, Issue 1 Newsletter Date Overview of Project—Robert J. Durán, Ph.D. During the Spring semester of 2012, I taught my final applied gang research class at New Mexico State Universi- ty. This was the third participatory Inside this action research course for undergrad- uate students I taught. The students issue: selected the communities of Anthony, Chaparral and Sunland Park (near Las Anthony, New 2-7 Cruzes) in New Mexico, and El Paso Mexico and Horizon City in Texas. Similar to previous years, the students evaluated the data obtained and ranked the level Chaparral, 8- of seriousness of gangs. These con- New Mexico 10 clusions were reached after reviewing the national gang literature. Please be aware that everything included is not Las Cruces, 11 related to or involved with gangs but New Mexico -18 is more of a reflection of the art and style of a particular geographic re- gion. The conclusions reached by my Sunland Park, 19- New Mexico 25 students were definitely influenced by whom they spoke to and what they were observing. Many of the students El Paso, Texas 26- were from these same communities 30 but most did not have any prior asso- every sentence to bring greater clarity ciation with gangs. Some of the com- ments provided read more as opinion to these responses. Although it has been eight years since the data for this Horizon City, 31- than based upon actual data whereas gang update was acquired, I hope it Texas 34 other points were very insightful and can serve as a model for highlighting established through teamwork. -

History of Gangs in the United States

1 ❖ History of Gangs in the United States Introduction A widely respected chronicler of British crime, Luke Pike (1873), reported the first active gangs in Western civilization. While Pike documented the existence of gangs of highway robbers in England during the 17th century, it does not appear that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious street gangs. Later in the 1600s, London was “terrorized by a series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys [and they] fought pitched battles among themselves dressed with colored ribbons to distinguish the different factions” (Pearson, 1983, p. 188). According to Sante (1991), the history of street gangs in the United States began with their emer- gence on the East Coast around 1783, as the American Revolution ended. These gangs emerged in rapidly growing eastern U.S. cities, out of the conditions created in large part by multiple waves of large-scale immigration and urban overcrowding. This chapter examines the emergence of gang activity in four major U.S. regions, as classified by the U.S. Census Bureau: the Northeast, Midwest, West, and South. The purpose of this regional focus is to develop a better understanding of the origins of gang activity and to examine regional migration and cultural influences on gangs themselves. Unlike the South, in the Northeast, Midwest, and West regions, major phases characterize gang emergence. Table 1.1 displays these phases. 1 2 ❖ GANGS IN AMERICA’S COMMUNITIES Table 1.1 Key Timelines in U.S. Street Gang History Northeast Region (mainly New York City) First period: 1783–1850s · The first ganglike groups emerged immediately after the American Revolution ended, in 1783, among the White European immigrants (mainly English, Germans, and Irish). -

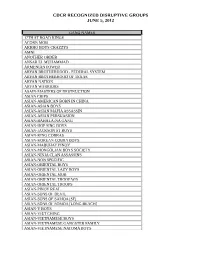

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

HISTORY of STREET GANGS in the UNITED STATES By: James C

Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice NATIO N AL GA ng CE N TER BULLETI N No. 4 May 2010 HISTORY OF STREET GANGS IN THE UNITED STATES By: James C. Howell and John P. Moore Introduction The first active gangs in Western civilization were reported characteristics of gangs in their respective regions. by Pike (1873, pp. 276–277), a widely respected chronicler Therefore, an understanding of regional influences of British crime. He documented the existence of gangs of should help illuminate key features of gangs that operate highway robbers in England during the 17th century, and in these particular areas of the United States. he speculates that similar gangs might well have existed in our mother country much earlier, perhaps as early as Gang emergence in the Northeast and Midwest was the 14th or even the 12th century. But it does not appear fueled by immigration and poverty, first by two waves that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious of poor, largely white families from Europe. Seeking a street gangs.1 More structured gangs did not appear better life, the early immigrant groups mainly settled in until the early 1600s, when London was “terrorized by a urban areas and formed communities to join each other series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, in the economic struggle. Unfortunately, they had few Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys … who found amusement in marketable skills. Difficulties in finding work and a place breaking windows, [and] demolishing taverns, [and they] to live and adjusting to urban life were equally common also fought pitched battles among themselves dressed among the European immigrants. -

INDICTMENT ENRIQUE GUAJARDO LOPEZ, A/K/A "Kid," A/Lila "Kike," CRIMINAL NO

Case 3:10-cr-02213-KC Document 930 Filed 03/19/12 Page 1 of 57 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS EL PASO DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA SEALED V. THIRD SUPERSEDING INDICTMENT ENRIQUE GUAJARDO LOPEZ, a/k/a "Kid," a/lila "Kike," CRIMINAL NO. EP1OCR2213 JOSEANTONIOACOSTAHERNANDE4 a/k/a "Diego," ak/a "Dienton," a/lila "I)ie" CT 1: 18 U.S.C. § 1962(d); Conspiracy a/lila "Bablazo," to Conduct the Affairs of an Enterprise EDUARDO RAVELO, through a Pattern of Racketeering a,k/a'91'ablas," a/kfa"Tablem," a/k/a '91'-BJas," Activity. aik/a "2x4," a/k/a "Bias," a/k/a "Lumberman," CT 2: 21 U.S.C. § 846; Conspiracy to a/k/a "Boards," a/k/a "56," Distribute and Possess with the Intent to LUJS MENDEZ4 Distribute Controlled Substances. a/k/a "A1," a/k'a CT 3: 21 U.S.C. § 963; Conspiracy to ARTURO GAILEGOS CASTREILON, Import Controlled Substances. a/k/a "Benny," a/k/a "Farmero," ak/a "51:' CT 4: 18 U.S.C. § 1956(h); Conspiracy ailda"Guero," a/k/a 'Pecas," a/k/a ''ury," to Launder Monetary Instruments. a/k/a "86," CT 5: 18 U.S.C. § 956(a)(1); Conspiracy RICARDOVALLFS DE LA ROSA, to Kill Persons in a Foreign Country. a/Ida "Chino," a/Ida "Come Arroz," CT 6-8: 18 U.S.C. § 924(c) & (j); a/k/a "99," Murder Resulting from the Use and ALBERrON'UNEZPAYAN, Carrying of a Firearm During and in ailila "Fresa," a/k/a "Fresco," a/k/a "97," Relation to Crimes of Violence and Drug JOSE GUADALUPE DIAL DIAL, Trafficking.