June 1994 150492- U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwest Border Gang Recognition

SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Sheriff Sigifredo Gonzalez, Jr. Zapata County, Texas Army National Guard Project April 30th, 2010 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 1 of 19 Pages SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Lecture Outline I. Summary Page 1 II. Kidnappings Page 6 III. Gangs Page 8 IV. Overview Page 19 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 2 of 19 Pages Summary The perpetual growth of gangs and active recruitment with the state of Texas, compounded by the continual influx of criminal illegal aliens crossing the Texas-Mexico border, threatens the security of all U.S. citizens. Furthermore, the established alliances between these prison and street gangs and various drug trafficking organizations pose a significant threat to the nation. Gangs now have access to a larger supply of narcotics, which will undoubtedly increase their influence over and presence in the drug trade, as well as increase the level of gang-related violence associated with illegal narcotics trafficking. Illegal alien smuggling has also become profitable for prison and other street gangs, and potentially may pose a major threat to national security. Multi-agency collaboration and networking—supplemented with modern technology, analytical resources, and gang intervention and prevention programs—will be critical in the ongoing efforts to curtail the violence associated with the numerous gangs now thriving in Texas and the nation.1 U.S.-based gang members are increasingly involved in cross-border criminal activities, particularly in areas of Texas and California along the U.S.—Mexico border. Much of this activity involves the trafficking of drugs and illegal aliens from Mexico into the United States and considerably adds to gang revenues. -

Chapter 1 the Emergence of Gangs in the United States— Then and Now

Chapter 1 The Emergence of Gangs in the United States— Then and Now CHAPTER OBJECTIVES î Examine the emergence of gangs in the United States. î Explore where gangs from New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles first emerged. î Identify the differences and similarities between each regions growth of gangs. î Examine the emergence of Black and Hispanic/Latino gangs. î Describe the newest gang trends throughout the United States. “The Cat’s Alleys,” the Degraw Street Gang, the Sackett Street gang, “The Harrisons,” the Bush Street Gang, and 21 other boys’ gangs were the subjects of a report of the New York State Crime Commission which told, last week, of its findings in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. The boys who comprise the gangs have to undergo rigorous initiations before being qualified for membership. In one of the more exclusive gangs initiates, usually aged about nine, have to drink twelve glasses of dago-red wine and have a revolver pressed into their temples while they take the pledge. Source: Gangs (1927). Time, 9(13), 11. Introduction The above excerpt comes from a 1927 article in Time Magazine that identifies local gangs in New York City and their activities. However, gangs existed long before any established city in the United States. British crime chronicler, Luke Pike (1873), reported that the first 1 ch01.indd 1 12/23/15 9:08 AM 2 Chapter 1: The Emergence of Gangs in the United States—Then and Now set of active gangs were in Europe. During those times, they were better known as highway robbers. -

History of Gangs in the United States

1 ❖ History of Gangs in the United States Introduction A widely respected chronicler of British crime, Luke Pike (1873), reported the first active gangs in Western civilization. While Pike documented the existence of gangs of highway robbers in England during the 17th century, it does not appear that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious street gangs. Later in the 1600s, London was “terrorized by a series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys [and they] fought pitched battles among themselves dressed with colored ribbons to distinguish the different factions” (Pearson, 1983, p. 188). According to Sante (1991), the history of street gangs in the United States began with their emer- gence on the East Coast around 1783, as the American Revolution ended. These gangs emerged in rapidly growing eastern U.S. cities, out of the conditions created in large part by multiple waves of large-scale immigration and urban overcrowding. This chapter examines the emergence of gang activity in four major U.S. regions, as classified by the U.S. Census Bureau: the Northeast, Midwest, West, and South. The purpose of this regional focus is to develop a better understanding of the origins of gang activity and to examine regional migration and cultural influences on gangs themselves. Unlike the South, in the Northeast, Midwest, and West regions, major phases characterize gang emergence. Table 1.1 displays these phases. 1 2 ❖ GANGS IN AMERICA’S COMMUNITIES Table 1.1 Key Timelines in U.S. Street Gang History Northeast Region (mainly New York City) First period: 1783–1850s · The first ganglike groups emerged immediately after the American Revolution ended, in 1783, among the White European immigrants (mainly English, Germans, and Irish). -

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

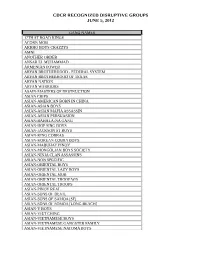

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

The Changing Social Organization of Prison Protection Markets: When Prisoners Choose to Organize Horizontally Rather Than Vertically

Trends Organ Crim https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-018-9332-0 The changing social organization of prison protection markets: when prisoners choose to organize horizontally rather than vertically R. V. Gundur1 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract This article revisits the framework which Buentello et al. (Prison J 71(2): 3– 14, 1991) created to describe the development of inmate solidarity groups into prison gangs in the Texas Department of Corrections. Interviews with current and former prison gang members in Texas, Arizona, and Illinois augment the current published literature on prison gangs in California. This article argues that the responses which prison administrations make to prisoners’ social orders are not static and have, in some cases, caused vertically configured groups to evolve into horizontally configured groups. These structural changes in prison gangs affect the gangs’ ability to affect control in the criminal underworld outside prison. Accordingly, although the challenges which prison administrations present to vertically developed social orders within prison may improve the administrations’ control within the prison walls, they may effectively decrease criminal-led social control on the street, leading to an increase in street-level violence. Keywords Prison gangs . Security threat groups . Social order. Protection rackets . Prisons . Organized crime Introduction To date, the majority of research undertaken, by academics and practitioners alike, on Bprison gangs,^ formally known as Bsecurity threat groups,^ focuses on vertically organized groups (Buentello et al. 1991; Fleisher and Decker 2001; Fong 1990; Orlando-Morningstar 1997; Pyrooz et al. 2011;Skarbek2014). The model of prison * R. V. Gundur [email protected] 1 Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK Trends Organ Crim gang development proposed by Buentello et al. -

HISTORY of STREET GANGS in the UNITED STATES By: James C

Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice NATIO N AL GA ng CE N TER BULLETI N No. 4 May 2010 HISTORY OF STREET GANGS IN THE UNITED STATES By: James C. Howell and John P. Moore Introduction The first active gangs in Western civilization were reported characteristics of gangs in their respective regions. by Pike (1873, pp. 276–277), a widely respected chronicler Therefore, an understanding of regional influences of British crime. He documented the existence of gangs of should help illuminate key features of gangs that operate highway robbers in England during the 17th century, and in these particular areas of the United States. he speculates that similar gangs might well have existed in our mother country much earlier, perhaps as early as Gang emergence in the Northeast and Midwest was the 14th or even the 12th century. But it does not appear fueled by immigration and poverty, first by two waves that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious of poor, largely white families from Europe. Seeking a street gangs.1 More structured gangs did not appear better life, the early immigrant groups mainly settled in until the early 1600s, when London was “terrorized by a urban areas and formed communities to join each other series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, in the economic struggle. Unfortunately, they had few Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys … who found amusement in marketable skills. Difficulties in finding work and a place breaking windows, [and] demolishing taverns, [and they] to live and adjusting to urban life were equally common also fought pitched battles among themselves dressed among the European immigrants. -

What Have We Learned About Prison Gangs? Findings from the Lonestar Project

What have we learned about prison gangs? Findings from the LoneStar Project David C. Pyrooz, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Institute of Behavioral Science University of Colorado Boulder A Presentation to the UTEP Center for Law & Human Behavior Email: [email protected] Phone: (303) 492-3241 The LoneStar Project Twitter: @dpyrooz This project was supported by Grant No. 2014-MU-CX-0111 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, and was made possible with the assistance of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Justice or the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Understanding prison gangs SCHEDULE1. The problem of prison gangs 2. The LoneStar Project 3. Characteristics of prison gangs/gang members 4. Power and control on the inside 5. Q & A Responding to gangs 1. Joining/leaving in prison 2. Criminal and gang recidivism 3. Renouncement and disassociation 4. Policy/program implications 5. Q & A The LoneStar Project The problem of prison gangs 25% Winterdyk & Ruddell (2010) 19% N=37 20% NGIC (2011) Pyrooz & Mitchell 15% N=N/A (2018) 15% N=38 Hill 15% Wells et al. (2009) (2002) 12%, N=38 10% N=39 10% Camp & Camp (1985) 3% N=23 5% % of Prison Population, Gang Affiliated Gang Population, ofPrison % 0% 1984 2002 2008 2009 2011 2016 SOME INCONCLUSIVE “FACTS” • Misconduct, particularly violence • Orchestration -

An Overview of the Challenge of Prison Gangs

An Overview of theOverview Challenge of the Challenge of Prisonof Gangs 1 Prison Gangs Mark S. Fleisher and Scott H. Decker A persistently disruptive force in merica now imprisons men and women correctional facilities is prison gangs. with ease and in very large numbers. At the Prison gangs disrupt correctional end of the year 2000, an estimated two mil- lion men and women were serving prison programming, threaten the safety of Aterms. The mission of improving the quality of life inmates and staff, and erode institutional inside our prisons should be a responsibility shared quality of life. The authors review the by correctional administrators and community citi- history of, and correctional mechanisms to zens. Prisons are, after all, public institutions sup- cope with prison gangs. A suppression ported by tens of millions of tax dollars and what strategy (segregation, lockdowns, happens inside of these costly institutions will deter- mine to some degree the success inmates will have transfers) has been the most common after their release. Oddly though, citizens often be- response to prison gangs. The authors lieve that anyone can offer an intelligent opinion argue, however, that given the complexity about prison management and inmate program- of prison gangs, effective prison gang ming. In recent years, elected officials have called for intervention must include improved tougher punishment in prisons, stripping color tele- strategies for community re-entry and visions, removing weightlifting equipment, and weakening education programs as if doing these more collaboration between correctional rather trivial things will punish inmates further and agencies and university gang researchers force them to straighten out their lives and will scare on prison gang management policies and others away from crime. -

Criminal Insurgency in the Americas and Beyond

Criminal Insurgency in the Americas and Beyond BY ROBERT KILLEBREW ven before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the global context for American secu- rity policy was changing. While the traditional state-based international system continued E to function and the United States reacted to challenges by states in conventional ways (for example, by invading Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11), a cascade of enormous technological and social change was revolutionizing international affairs. As early as the 1990s, theorists were writing that with modern transnational communications, international organizations and corporate con- glomerates would increasingly act independently of national borders and international regulation.1 What was not generally foreseen until about the time of 9/11, though, was the darker side: that the same technology could empower corrupt transnational organizations to threaten the international order itself. In fact, the globalization of crime, from piracy’s financial backers in London and Nairobi to the Taliban and Hizballah’s representatives in West Africa, may well be the most important emerging fact of today’s global security environment. Transnational crime operates on a global scale, and the criminal networks that affect national security include actors ranging from Russian mafias to expanding Asian drug-trafficking organiza- tions in U.S. cities. Without discounting their importance, this article focuses on illegal groups native to this hemisphere and particularly Latin America, those identified by the Department of Justice as posing the most significant organized criminal threat to U.S. security. Two factors related Colonel Robert Killebrew, USA (Ret.), is a Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security. -

I.Ernesto Cordero

el periódico de la vida nacional $12.00 Año XCIV-Tomo I, Número 34,096• México, D.F. • 80 páginas ma r te s 1 1 de enero de 2011 www.excelsior.com.mx < adrenalina > < función > La Pulga dorada se muere el bUeno Lionel Messi, quien tuvo un Mundial muy malo, pero una Le vamos a contar eL finaL: matan a uno temporada excelente, ganó de Los cuatro fantásticos. así Lo dio a por segunda vez el Balón de conocer marveL, La editora deL cómic. Oro al mejor futbolista. no especificó quién será La víctima. Fotos: Reuters y Especial pemex nO hA emitIdO licItAcIón La refinería, para el 2016 Sigue en fase de “ingeniería conceptual”; en 2012 se decidirá quién hará el complejo POR AtZAyAELh tORRES enviaron invitaciones a posibles compañías licenciadoras de los Subejercicio La nueva refinería de Tula, Hi- principales procesos industria- dalgo, apenas se encuentra en les, posteriormente desarrolla- de 27% en día de héroes y de dolor fase de conceptualización, ad- remos la ingeniería básica de las mitió Petróleos Mexicanos. plantas”. Paralelamente, man- obras de 2010 Arizona rechaza a los hispanos, pero fue uno de ellos La primera licitación para tienen “conversaciones con la el que estabilizó a la congresista Gabrielle Giffords construirla se emitirá el primer Comisión Federal de Electrici- El año pasado, la Se- 6 trimestre de 2012, y entrará en dad para analizar el esquema de >cretaría de Comunica- tras el atentado que la dejó gravemente he rida. El MuErtos operación en 2016. cogeneración en la nueva refine- ciones y Transportes tuvo un presidente Barack Obama y su esposa, en tan to, de di Actualmente, “el Instituto ría”, se lee en el texto. -

The Criminal Organization

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Organized Crime in North America and the World: Complete Bibliography A Bibliography September 2017 Part 4: The rC iminal Organization Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/bibliography Recommended Citation "Part 4: The rC iminal Organization" (2017). Complete Bibliography. 5. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/bibliography/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Organized Crime in North America and the World: A Bibliography at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Complete Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Part Four: The Criminal Organization This part of the bibliography provides references to literature that describes and/or examines the criminal organization in depth. Particular emphasis is placed on works that explore salient issues relating to the organization of crime, such as group structure, membership, recruitment, codes, etc. Adams, James. 1991. “Medellin Cartel.” American Spectator. 24: December: 22-5. Albini, J. L. 1975.”Mafia As Method: A Comparison Between Great Britain and U.S.A. Regarding the Existence and Structure of Types of Organized Crime.” International Journal of Criminology and Penology. 3: 295-305. Bossard, Andre. 1998. “Mafias, Triads, Yakuza and Cartels: A Comparative Study of Organized Crime.” Crime and Justice International. 14(December): 5-32. Chu, Yiu Kong. 2000. The Triads As Business. Routledge Studies in Modern History of Asia, 6. Routledge. Coleman, James W. 1982. “The Business of Organized Crime: A Cosa Nostra Family.” American Journal of Sociology. 88(1, July): 235. Coles, Nigel. -

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE 1203 27305 WEST LIVE OAK ROAD CASTAIC, CA 91384-4520 FOIPA Request No.: 1374338-000 Subject: List of FBI Pre-Processed Files/Database Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your Freedom of Information/Privacy Acts (FOIPA) request. The FBI has completed its search for records responsive to your request. Please see the paragraphs below for relevant information specific to your request as well as the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for standard responses applicable to all requests. Material consisting of 192 pages has been reviewed pursuant to Title 5, U.S. Code § 552/552a, and this material is being released to you in its entirety with no excisions of information. Please refer to the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for additional standard responses applicable to your request. “Part 1” of the Addendum includes standard responses that apply to all requests. “Part 2” includes additional standard responses that apply to all requests for records about yourself or any third party individuals. “Part 3” includes general information about FBI records that you may find useful. Also enclosed is our Explanation of Exemptions. For questions regarding our determinations, visit the www.fbi.gov/foia website under “Contact Us.” The FOIPA Request number listed above has been assigned to your request. Please use this number in all correspondence concerning your request. If you are not satisfied with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s determination in response to this request, you may administratively appeal by writing to the Director, Office of Information Policy (OIP), United States Department of Justice, 441 G Street, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, D.C.