Peering Through the Trees, Or, Everything I've Ever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13Th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13Th Part 2 Review

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13th part 2 review. Vickie didnt want to disturb Jeff and Sandra. She had heard the vigorous sounds coming from their bedroom, and knew they must be lying exhausted in each others arms by now. But she had to see them. She had to warn them what was happening here at Crystal Lake, as thunder crashed and lightning flashed. Timidly she opened the bedroom door and looked inside. The sheets were pulled over two figures lying on the bed. Sandra, Vickie whispered. Then the sheet was thrown back, and a hooded figure sat up. and Vickie screamed and screamed and screamed. Dr. Wolfula- "Friday the 13th Part 2" Review. User Reviews. Check out what Sophie had to say about the corresponding Freddy pic here! With Mrs. Voorhees with no head and a cliffhanger of an ending, writer Ron Kurz and director Steve Miner had a few roads to travel in unraveling more of the slasher franchise. The camp slasher foundation continues its build, but the introduction of a soon to be iconic killer makes the film feel fresh and exciting with a surprising attention to detail. Alice Hardy has survived the attacks of crazy Mrs. Voorhees and decides to gain back her normalcy in a summer vacation home. The dream of a decomposed young Jason still haunt her, as does the head of Pamela flying from her neck. Forgot your password? Don't have an account? Sign up here. By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and Fandango. -

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, Et Al

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, et al. Summer Camp Scares I Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th I Still Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th Part 2 All The Boys Love Mandy Lane Friday the 13th Part III The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) Sleepaway Camp The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers House of Wax Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland Wolf Creek The Final Girls Wolf Creek 2 Stage Fright Psycho Beach Party The Burning Club Dread Campfire Tales Disturbia Addams Family Values It Follows The Devil’s Rejects Creepy Cabins in the Woods Blood Beach Cabin Fever The Lost Boys The Cabin in the Woods Straw Dogs The Evil Dead The Town That Dreaded Sundown Evil Dead 2 VACATION NIGHTMARES IT Evil Dead Hostel Ghost Ship Tucker and Dale vs Evil Hostel: Part II From Dusk till Dawn The Hills Have Eyes Death Proof Eden Lake Jeepers Creepers Funny Games Turistas Long Weekend AQUATIC HORROR, SHARKS, & ANIMAL ATTACKS Donkey Punch Jaws An American Werewolf in London Jaws 2 An American Werewolf in Paris Jaws 3 Prey Joyride Jaws: The Revenge Burning Bright The Hitcher The Reef Anaconda Borderland The Shallows Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid Tourist Trap 47 Meters Down Lake Placid I Spit On Your Grave Piranha Black Water Wrong Turn Piranha 3D Rogue The Green Inferno Piranha 3DD Backcountry The Descent Shark Night 3D Creature from the Black Lagoon Deliverance Bait 3D Jurassic Park High Tension Open Water The Lost World: Jurassic Park II Kalifornia Open Water 2: Adrift Jurassic Park III Open Water 3: Cage Dive Jurassic World Deep Blue Sea Dark Tide mrandmrshalloween.com. -

Friday the 13Th: Resurrection Table of Contents TABLE of CONTENTS

Friday the 13th Resurrection V0.5 By Michael Tresca D20 System and D&D is a trademark of Wizards of the Coast, Inc.©. All original Friday the 13th images and logos are copyright of their respected companies: © 2000/2001 Crystal Lake Entertainment / New Line Cinema. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks and copyrights are cited in this document without permission. This usage is not meant in any way to challenge the rightful ownership of said trademarks/copyrights. All copyrights are acknowledged and remain the property of the owners. Epic Undead Jason Voorhees, Corpse template, and the Slasher class were created by DarkSoldier's D20 Modern Netbook of Famous Characters. This game is for entertainment only. This document utilizes the Friday the 13th and Ghosttown fonts. You can get the latest version of this document at Talien's Tower, under the Freebies section. WARNING: This document contains spoilers of the movies and games. There. You've been warned! 2 - Friday the 13th: Resurrection Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................6 SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................................6 CAMPAIGN IN BRIEF......................................................................................................................................6 -

Star Channels, Oct. 25

OCTOBER 25 - 31, 2020 staradvertiser.com THRILLING DRAMA Shortly after Grace (Nicole Kidman) becomes intrigued by another mother at her son’s school, tragedy strikes the school community in the premiere of The Undoing. Grace’s life begins to unravel as she realizes her missing husband, Jonathan (Hugh Grant), may not be the man she thoughtshe knew. Airing Sunday, Oct. 25, on HBO. We’ve given each candidate five minutes to impress you. Hear the candidates explain their platform in five minutes or less. You listen, you decide, and by November 3rd, you vote. For candidate info, debates and forums, visit olelo.org/CIF CANDIDATES IN FOCUS | CHANNEL 49 NOW–NOVEMBER 2 | 7AM, 1PM & 7PM olelo.org 590230_CandidatesInFocus_2_General.indd 1 10/20/20 4:10 PM ON THE COVER | THE UNDOING Big drama, small screen ‘The Undoing’ premieres When the series opens, Grace becomes with a fascinating, complicated female role at fascinated with another mom from her son’s its center,” Kidman said in an official HBO.com on HBO school. Shortly thereafter, tragedy strikes release. the school community, setting off a chain of Lauded as one of the most successful ac- By Kyla Brewer events that leads Grace to question whether tors of her generation, Oscar, Golden Globe and TV Media she really knew her now-missing husband as Emmy winner Kidman first came to the atten- she deals with a very public disaster. All the tion of American audiences in such films as s movie theaters struggle to survive in while, she tries to come to terms with the fact “Days of Thunder” (1990) and “Far and Away” the wake of shutdowns caused by the that she’s failed to heed her own advice as she (1992). -

Jay Pharoah Could Become 'White Famous'

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad October 13 - 19, 2017 We’ve got you covered! waxahachietx.com A C O L L A B O R A T I V E C 2 x 3" ad M J C H N E D F H S C O I D H Your Key B B A M A X Z Y E Q E M T N A To Buying U V Z M Q R Z I X S J C K U V 2 x 3.5" ad D G M A I L R F S A O N Z T I and Selling! K Q S L C E V R R D R F T G S A A I C S B N H E I P Y U J M R S N O Z Y X P C E O L N I K Z D A L A X D G U P J L A M B R C I M O G H Q D U O I M Z C O H D F L O Y D O T G H E Y U V K E Q W E R Q R T Y U L U I E L M N H G P O P H A R O A H R G O K S Z A Q W S X I C J E T A C F Q A Z X S W E D B M N Jay Pharoah could “White Famous” on Showtime (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Jamie (Jamie) Foxx (Seriocomic) Series Place your classified Solution on page 13 Floyd (Mooney) (Jay) Pharoah (Movie) Producer ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Trevor (Lonnie) Chavis (Very) Collaborative Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and become ‘White Sadie (Cleopatra) Coleman (Stand-Up) Comedian Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Malcolm (Utkarsh) Ambudkar (Transitional) Project Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it Famous’ Jay Pharoah (right) plays a version of Jamie Foxx in “White Famous,” 2 x 3.5" ad premiering Sunday on Showtime. -

The Horror Collection 03

@ An Eaglemoss Publication Every fortnight UK £6.99 Malta LM5.60 The hockey mask that became a horror icon JHBorfy oorhees Masked Menace Movie nioiiiiaS ^ The moment that made a horror icon - Jason with mask and machete. Jason Voorhees Masked Menace The Crystal Lake slasher in his most unmistakable guise. The slasher movie goes stereoscopic ~ the startling 3-D effects in Part 3. hifiiite sfopy / The Friday The 13th phenomenon ‘ T - how It all began. Fear factor Find out how the movie-makers have us hooked even before the film is released. Ato Z of Ipoppoi* Delve into more juicy facts and trivia I / about weapons, themes and characters.J?[ f Alan Jones is an ind Inally recagnis»d horror expert. Author of thd dling The Rough Guide to Horror Movi^t ||s for Fangoria and VISIT W^^SIT^ regularly tuming up«i| the UK's biggest horrorl www.horror-collectjon.co.uk It's been a long night at the lake and homicidal monster Jason Vooriiees goes head to head with the final teenager, Chris Higgins. Here, for the very first time in Friday The 13fh history, we see Jason as the icon of popular culture he has now become - bearing hockey mask and machete. V % It is during the last campaign of carnage in Friday The 13th Part 3 that we f ' witness Jason as he would never be forgotten. As the action moves to the barn, the Trademark • That infamous only surviving teenager, Chris Higgins, is machete gripped goalie mask, now seemingly trapped. There's nowhere to reedy to malm synonymous with run, nowhere to hide.. -

Title Catalog Link Section Call # Summary Starring 28 Days Later

Randall Library Horror Films -- October 2009 Check catalog link for availability Title Catalog link Section Call # Summary Starring 28 days later http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. DVD PN1995.9. An infirmary patient wakes up from a coma to Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, edu/record=b1917831 Horror H6 A124 an empty room ... in a vacant hospital ... in a Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns, 2003 deserted city. A powerful virus, which locks Brendan Gleeson victims into a permanent state of murderous rage, has transformed the world around him into a seemingly desolate wasteland. Now a handful of survivors must fight to stay alive, 30 days of night http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. DVD PN1995.9. An isolated Alaskan town is plunged into Josh Hartnett, Melissa George, Danny edu/record=b2058882 Horror H6 A126 darkness for a month each year when the sun Huston, Ben Foster, Mark Boone, Jr., 2008 sinks below the horizon. As the last rays of Mark Rendall, Amber Sainsbury, Manu light fade, the town is attacked by a Bennett bloodthirsty gang of vampires bent on an uninterrupted orgy of destruction. Only the town's husband-and-wife Sheriff team stand 976-EVIL http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. VHS PN1995.9. A contemporary gothic tale of high-tech horror. Stephen Geoffreys, Sandy Dennis, edu/record=b1868584 Horror H6 N552 High school underdog Hoax Wilmoth fills up Lezlie Deane 1989 the idle hours in his seedy hometown fending off the local leather-jacketed thugs, avoiding his overbearing, religious fanatic mother and dreaming of a date with trailer park tempress Suzie. But his quietly desperate life takes a Alfred Hitchcock's http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. -

Friday the 13Th Part 3 Full Movie Download

Friday the 13th part 3 full movie download Continue February 12, 2015 at 1:11am As for Jason running, backing up, getting kicked in nuts, etc... I think they intentionally made it a little pathetic. He is mentally retarded, deformed, ashamed of his appearance (hence the mask and the bag over his head), he is uneducated and the child is like growing up without external influences, and his mother, whom he apparently misses, was brutally murdered. Despite being a furious-fueled killer, he is actually portrayed as a very human and vulnerable, at least in a banned WORD few movies before he becomes more of a lumbering zombie. Compare it to Michael Myers, who is a machine-like, soulless, invincible force even in the movie BANNED WORD. Thanks to Y2J420 for explaining why this kept disappearing earlier. This article contains a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it does not have enough relevant link. Please help improve this article by entering more accurate quotes. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to delete this message template) Friday's 13th Part 2Theatrical release posterDirected by Steve MinerProduced by Steve MinerWritten Ron Kurtz-basedCharactersby Victor Miller starring Amy Steel's Adrienne King John Furey Music by Harry ManfrediniCinetographyPeter SteinEdited by Susan E. CunninghamProductioncompany Georgetown ProductionsDistributed byParamount Pictures 1981 (1981-05-01) Running 87 Minutes Strange United StatesAngulageAngalbud $1.25 million Box Office$21.7 million Friday 13th Part 2 - American slasher 1981 , produced and directed by Steve Miner in his directorial debut , written by Ron Kurtz, and starring Amy Steele and John Furey. -

Dr. Fauci Talks About Hawai¶I's COVID-19 Surge

AUGUST 23 - 29, 2020 staradvertiser.com MYSTERY ABOUNDS While investigating a freak accident at Lady Matilda’s College, Endeavour Morse (Shaun Evans) becomes convinced that the incident is linked to other so-called accidents around Oxford in Masterpiece Mystery: Endeavour. The series serves as a prequel to the popular British detective drama Inspector Morse. Airing Sunday, Aug. 23, on PBS. Dr. Fauci talks about Hawai¶i’s COVID-19 surge. Join us as Lt. Governor Josh Green speaks with Dr. Anthony Fauci by videoconference. Dr. Fauci has advised six Presidents and is one of the world’s leading experts on infectious diseases. olelo.org CHANNEL 49 AND FACEBOOK LIVE | THURSDAY, AUG 27 | 7AM 590217_DrFauciAd_2in_R.indd 1 8/19/20 9:56 AM ON THE COVER | MASTERPIECE MYSTERY: ENDEAVOUR A complicated man Morse returns to solve ern television’s most unique detectives the unlikely pair tries to solve a number has returned. of homicides against the backdrop of the mysteries in ‘Endeavour’ Shaun Evans (“Teachers”) is back as gifted women’s liberation movement and increas- investigator DS Endeavour Morse in a new ing racial tensions in the ‘70s. episode of “Masterpiece Mystery: Endeavour,” As with all the previous “Endeavour” By Kyla Brewer airing Sunday, Aug. 23, on PBS. The British ITV episodes, each of the three Season 7 TV Media series serves as a prequel to the popular ‘80s installments was written by the show’s and ‘90s detective drama “Inspector Morse.” creator, Russell Lewis (“The Ambassador”). V sleuths have been staples of prime In “Endeavour,” Evans stars as the younger In an official ITV release about Season 7, time for ages, and with good reason. -

Tytuł Nośnik Sygnatura Commando DVD F.1 State of Grace DVD F.2 Black Dog DVD F.3 Tears of the Sun DVD F.4 Force 10 from Navaro

Tytuł Nośnik Sygnatura Commando DVD F.1 State of Grace DVD F.2 Black Dog DVD F.3 Tears of The Sun DVD F.4 Force 10 From Navarone DVD F.5 Palmetto DVD F.6 Predator DVD F.7 Hart's War DVD F.8 Three Kings DVD F.9 Antitrust DVD F.10 Prince of The City DVD F.11 Best Laid Plans DVD F.12 The Faculty DVD F.13 Virtuosity DVD F.14 Starship Troopers DVD F.15 Event Horizon DVD F.16 Outland DVD F.17 AI Artificial Intelligence DVD F.18 Aeon Flux DVD F19F.19 No Man's Land DVD F.20 War DVD F.21 Windtalkers DVD F.22 The Sea Wolves DVD F.23 Clay Pigeons DVD F.24 Stalag 17 DVD F.25 Young Lions DVD F.26 Where Eagles Dare DVD F.27 Patton DVD F.28 Das Boot - Director's Cut DVD F.29 The Thin Red Line DVD F.30 Robocop 3 DVD F.31 Screamers DVD F.32 Impostor DVD F.33 Prestige DVD F.34 Fracture DVD F.35 The Warriors DVD F.36 Color of Night DVD F.37 K-19 the Widowmaker DVD F.38 Scorpio DVD F.39 We Were Soldiers DVD F.40 Longest Day DVD F.41 Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas DVD F.42 Soldier of Orange DVD F.43 Pitch Black DVD F.44 Deathsport DVD F.45 Lathe of Heaven DVD F.46 Dark City DVD F.47 Enemy of The State DVD F.48 Quills DVD F.49 Mr Brooks DVD F.50 Almost Famous DVD F.51 Broadcast News DVD F.52 Great Escape DVD F.53 From Here to Eternity DVD F.54F.54 Soldier DVD F.55 Deja VU DVD F.56 Hellboy DVD F.57 Renaissance Paris 2054 DVD F.58 Donnie Darko DVD F.59 Dirty Dozen DVD F.60 King Rat DVD F.61 Gi Jane DVD F.62 Earth VS The Flying Saucers DVD F.63 Catch Me If You Can DVD F.64 Run Silent, Run Deep DVD F.65 Marathon Man DVD F.66 8MM DVD F.67 Panic Room DVD F.68 Two Minute Warning DVD F.69 Switchback DVD F.70 The Day of The Jackal DVD F.71 Cape Fear DVD F.72 Deliverance DVD F.73 Journey to The Far Side of The Sun DVD F.74 Being John Malkovich DVD F.75 Alien Nation. -

The Last Final Girl Free

FREE THE LAST FINAL GIRL PDF Stephen Graham Jones | 216 pages | 30 Sep 2012 | Eraserhead Press | 9781621050513 | English | Portland, OR, United States The Last Final Girl by Stephen Graham Jones Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Life in a slasher film is easy. You just have to know when to The Last Final Girl. Aerial View: A suburban town in Texas. Everyone's got an automatic garage door opener. All the kids jump off a perilous cliff into a shallow river as a rite of passage. The sheriff is a local celebrity. You know this town. You're from this town. Zoom In: Homecoming princess, Lindsay. She's just barely escaped Life in a slasher film is easy. She's just barely escaped death at the hands of a brutal, sadistic murderer in a Michael Jackson mask. Up on the cliff, she was rescued by a horse and bravely defeated the killer, alone, bra-less. Her story is already a legend. She's this town's heroic final girl, their virgin angel. Monster Vision: Halloween masks floating down that same river the kids jump into. But just as one slaughter is not enough for Billie Jean, our masked killer, one victory is not enough for Lindsay. Her high The Last Final Girl is full of final girls, and she's not the only one who knows the rules of the game. -

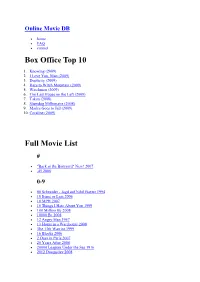

Box Office Top 10 Full Movie List

Online Movie DB home FAQ contact Box Office Top 10 1. Knowing (2009) 2. I Love You, Man (2009) 3. Duplicity (2009) 4. Race to Witch Mountain (2009) 5. Watchmen (2009) 6. The Last House on the Left (2009) 7. Taken (2008) 8. Slumdog Millionaire (2008) 9. Madea Goes to Jail (2009) 10. Coraline (2009) Full Movie List # "Back at the Barnyard" New! 2007 .45 2006 0-9 00 Schneider - Jagd auf Nihil Baxter 1994 10 Items or Less 2006 10 MPH 2007 10 Things I Hate About You 1999 100 Million Bc 2008 10000 Bc 2008 12 Angry Men 1957 13 Hours in a Warehouse 2008 The 13th Warrior 1999 16 Blocks 2006 2 Days in Paris 2007 20 Years After 2008 20000 Leagues Under the Sea 1916 2012 Doomsday 2008 21 2008 24 7: Twenty Four Seven 1997 25 to Life 2008 27 Dresses 2008 28 Weeks Later 2007 30,000 Leagues Under the Sea 2007 300 2007 The 300 Spartans 1962 305 2008 The 39 Steps 1935 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days 2007 42nd Street 1933 50 First Dates 2004 5ive Girls 2006 The 7th Voyage of Sinbad 1958 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag 1997 8 Mile 2002 88 Minutes 2008 9 Dead Gay Guys 2002 A A Beautiful Mind 2001 A Boy and His Dog 1975 A Bridge Too Far 1977 A Bronx Tale 1993 A Bucket of Blood 1959 A Bug's Life 1998 A Cinderella Story 2004 A Clockwork Orange 1971 A Countess from Hong Kong 1967 A Farewell to Arms 1932 A Few Good Men 1992 A Hard Day's Night 1964 A Knight's Tale 2001 A Lot Like Love 2005 A Matter of Life and Death 1946 A Midnight Clear 1992 A Mighty Heart 2007 A Night At the Roxbury 1998 A Nightmare on Elm Street 1984