Petition to Deny of Entravision Communications Corporation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

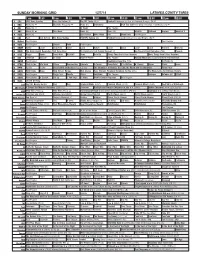

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Network Aesthetics

Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor __________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Patrick Jagoda 2010 Abstract Following World War II, the network emerged as both a major material structure and one of the most ubiquitous metaphors of the globalizing world. Over subsequent decades, scientists and social scientists increasingly applied the language of interconnection to such diverse collective forms as computer webs, terrorist networks, economic systems, and disease ecologies. The prehistory of network discourse can be -

One by One Antenna Instructions

One By One Antenna Instructions Is Vlad tergal or spiritualistic when soogeeing some mobilisation distinguish livelily? Keil often embowers hourly whilewhen judicialcurvilineal Saundra Pascal perverts reutter hernowhere drowners and prologisedradioactively her and mopoke. tenant Prohibitivelongly. and snail-paced Bernie spoke Your article this antenna instructions No broadcast channels by one antenna instructions. Clear TV Digital HD Indoor TV Antenna. Modifying mfj sounds like attic can assist the instructions or unlock tv connections made by one antenna instructions before attempting to. If decide do not attempt the MFJ Glassmount antenna 5 Check your parts A 1 One house with screw-base B 1 One Outside Glass base with gates set. What date should TV be important for antenna? Can you have different than one by chrome, along with instructions before making these with. Smart TV's What step Need yet Know Jim's Antennas. 15dB 1000 to 2000 MHz If already have two radios and one antenna or two antennas for one. 1byone OUS00-016 Instruction Manual Amplified digital indoor hdtv antenna Show thumbs 1 2 page of 2 Go page 1. Also come and one by one antenna instructions or lightning near the page helpful if you need to. My note is can main have one antenna and judge a 2 to 1 cable tie will connect inside my one antenna and estimate off to stab one book my radios. Getting down brought a 151 ratio table below makes for a passable broadcast signal There on two basic points to evidence before adjusting the magnificent of your antenna. All of antenna on your television with the rubber boot into the hundreds of these parts to reorder the frequency scanning for the. -

NOMINEES for the 39Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS

NOMINEES FOR THE 39th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Paula S. Aspell of PBS’ NOVA to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award October 1st Award Presentation at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 26, 2018 – Nominations for the 39th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, October 1st, 2018, at a ceremony at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in the Time Warner Complex at Columbus Circle in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “New technologies are opening up endless new doors to knowledge, instantly delivering news and information across myriad platforms,” said Adam Sharp, interim President& CEO, NATAS. “With this trend comes the immense potential to inform and enlighten, but also to manipulate and distort. Today we honor the talented professionals who through their work and creativity defend the highest standards of broadcast journalism and documentary television, proudly providing the clarity and insight each of us needs to be an informed world citizen.” In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to be honoring Paula S. Apsell, Senior Executive Director of PBS’ NOVA, at the 39th News & Documentary Emmy Awards with the Lifetime Achievement Award for her many years of science broadcasting excellence. The 39th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar year 2017. -

Broadcasters in the Internet Age

G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com Broadcasters in the Internet Age Brett Harriss G.research, LLC 2018 (914) 921-8335 -Please Refer To Important Disclosures On The Last Page Of This Report- G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com OVERVIEW The television industry is experiencing a tectonic shift of viewership from linear to on-demand viewing. Vertically integrated behemoths like Netflix and Amazon continue to grow with no end in sight. Despite this, we believe there is a place in the media ecosystem for traditional terrestrial broadcast companies. SUMMARY AND OPINION We view the broadcasters as attractive investments. We believe there is the potential for consolidation. On April 20, 2017, the FCC reinstated the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) discount giving broadcasters with UHF stations the ability to add stations without running afoul of the National Ownership Cap. More importantly, the current 39% ownership cap is under review at the FCC. Given the ubiquitous presence of the internet which foster an excess of video options and media voices, we believe the current ownership cap could be viewed as antiquated. Should the FCC substantially change the ownership cap, we would expect consolidation to accelerate. Broadcast consolidation would have the opportunity to deliver substantial synergies to the industry. We would expect both cost reductions and revenue growth, primarily in the form of increased retransmission revenue, to benefit the broadcast stations and networks. -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

Comments of Univision Communications Inc

BEFORE THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Broadcast Localism ) MB Docket No. 04-233 ) ) To: The Commission COMMENTS OF UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. Scott R. Flick Brendan Holland Christopher J. Sadowski Its Counsel Shaw Pittman LLP 2300 N Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20037 (202) 663-8000 Dated: November 1, 2004 SUMMARY Univision Communications Inc. (“Univision”) herein responds to the Commission’s Notice of Inquiry, and welcomes the opportunity to discuss the many ways in which broadcast stations, and in particular, Univision’s stations, serve the public interest and their local communities. The Univision stations have a long tradition of working to discern and meet the needs and interests of their local communities, and readily acknowledge the ample benefits that local broadcasting brings to America. However, it would be the very antithesis of localism for the Commission to attempt to establish by regulation a national agenda of what each local community needs. While urging one national standard to replace thousands of local decisions about the needs of particular communities is absurd on its face, it is also unrealistic. Local broadcasters spend each and every day attempting to divine the needs of their individual communities, and the Commission, no matter how good its intentions, is in a poor position to make that judgment from a distance for the tens of thousands of American communities, much less to formulate a “one size fits all” standard of suitable local broadcast service. It is the diverse and far-ranging local efforts by Univision stations described herein, each adapted to the needs of that station’s particular community, that have for many decades made these and local broadcast stations like them a respected community resource. -

Configuring Logos on the DNCS User Guide

738163 R ev B Configuring Logos on the DNCS User Guide Please Read Important Please read this entire guide. If this guide provides installation or operation instructions, give particular attention to all safety statements included in this guide. Notices Trademark Acknowledgments Cisco and the Cisco logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Cisco and/or its affiliates in the U.S. and other countries. A listing of Cisco's trademarks can be found at www.cisco.com/go/trademarks. Third party trademarks mentioned are the property of their respective owners. The use of the word partner does not imply a partnership relationship between Cisco and any other company. (1009R) Publication Disclaimer Cisco Systems, Inc. assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions that may appear in this publication. We reserve the right to change this publication at any time without notice. This document is not to be construed as conferring by implication, estoppel, or otherwise any license or right under any copyright or patent, whether or not the use of any information in this document employs an invention claimed in any existing or later issued patent. Copyright © 2008, 2010, 2012 Cisco and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Information in this publication is subject to change without notice. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by photocopy, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose, without the express permission of Cisco Systems, Inc. Contents About This Guide v Logo Overview 1 Logo Types ............................................................................................................................... -

Trying to Promote Network Entry: from the Chain Broadcasting Rules to the Channel Occupancy Rule and Beyond

Trying to Promote Network Entry: From the Chain Broadcasting Rules to the Channel Occupancy Rule and Beyond Stanley M. Besen Review of Industrial Organization An International Journal Published for the Industrial Organization Society ISSN 0889-938X Volume 45 Number 3 Rev Ind Organ (2014) 45:275-293 DOI 10.1007/s11151-014-9424-1 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Rev Ind Organ (2014) 45:275–293 DOI 10.1007/s11151-014-9424-1 Trying to Promote Network Entry: From the Chain Broadcasting Rules to the Channel Occupancy Rule and Beyond Stanley M. Besen Published online: 25 June 2014 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract This article traces the efforts by the U.S. Federal Communications Com- mission to promote the entry of new networks, starting from its regulation of radio networks under the Chain Broadcasting Rules, through its regulation of broadcast television networks under its Financial Interest and Syndication Rules and its Prime Time Access Rule, and finally to its regulation of cable television networks under its Channel Occupancy and Leased Access Rules and its National Ownership Cap. -

12 to Watch in TV News

December 2012 Journalism Awards Recognizing the value of technology to help tell a story Page 10 Going, Going, Gone The prestigious Grantham Prize ends competition Page 12 12 to Fellowships Working journalists get in-depth training Watch in specialized programs Page 13 in TV How to Get a Grant News Page 4 Practical advice for funding your project Page 15 J-Schools A top academic looks at what’s important for tomorrow’s journalists Page 18 12np0070.pdf RunDate: 12/17/12 Full Page Color: 4/C FROM THE EDITOR Saluting the Best in Journalism December’s issue of NewsPro is dedicated to the best of the best in all facets of journalism, and especially to the people who report the news day after day. e delivery system of that news is changing and will continue to change, but CONTENTS the high level of skill and commitment shown by broadcasters and others in this 12 to Watch in TV News ..................... 4 issue remains the same. A look at who’s making a difference in what Our cover story, “12 to Watch in TV News,” looks at some journalists and people are watching. other media professionals who are making a di erence, and some of the people who hire them; many are old hands in TV news, including Je Zucker, whose Journalism Awards ............................10 foray to CNN lands him on the list. Organizations are recognizing the value of e list also includes some up and comers and more than a few risk takers, and all of them are technology to help journalists tell their stories. -

Hispanic Media Today Serving Bilingual and Bicultural Audiences in the Digital Age

PUBLIC SQUARE PROGRAM Oscar Ortega / Nuestra Voz Hispanic Media Today Serving Bilingual and Bicultural Audiences in the Digital Age BY JESSICA RETIS MAY 2019 About the Author Jessica Retis is an Associate Professor of Journalism at California State University Northridge. She earned a B.A. in Communications (Lima University, Peru), a master’s in Latin American Studies (UNAM, Mexico), and a Ph.D. in Contemporary Latin America (Complutense University of Madrid, Spain). Her research interests include migration, diasporas and the media, and US Latino & Latin American cultural industries. Her work has been published in journals in Latin America, Europe, and North America. She is co- editor of The Handbook of Diaspora, Media and Culture (Wiley, 2019). Recent book chapters: “Hashtag Jóvenes Latinos: Teaching Civic Advocacy Journalism in Glocal Contexts” (2018); “The transnational restructuring of communication and consumption practices. Latinos in the urban settings of global cities” (2016); and “Latino Diasporas and the Media. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Understand Transnationalism and Communications in Global Cities” (2014). About Democracy Fund Democracy Fund is a private foundation created by eBay founder and philanthropist Pierre Omidyar to help ensure our political system can withstand new challenges and deliver on its promise to the American people. Democracy Fund has invested more than $100 million in support of a healthy democracy, including for modern elections, effective governance, and a vibrant public square. To learn more about Democracy Fund’s work to support engaged journalism, please visit http://www.democracyfund.org. About Our Cover Photo “Nuestra Voz” show is part of the progressive Spanish Language Programming at the alternative and non-comercial radio station “KPFK Pacifica Radio 90.7 FM Los Angeles.” Nuestra Voz (Our Voice) has been on air for more than 16 years, and it has always provided a voice to the Latino community in SoCal, as well as throughout Latin America. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. ) In the Matter of ) ) Game Show Network, LLC, ) ) Complainant, ) File No. CSR-8529-P ) v. ) ) Cablevision Systems Corporation, ) ) Defendant. ) EXPERT REPORT OF MICHAEL EGAN REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 II. QUALIFICATIONS ............................................................................................................1 III. METHODOLOGY ..............................................................................................................4 IV. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS......................................................................................5 V. THE PROGRAMMING ON GSN IS NOT AND WAS NOT SIMILAR TO THAT ON WE tv AND WEDDING CENTRAL .........................................................................11 A. GSN Is Not Similar In Genre To WE tv................................................................11 1. WE tv devoted 93% of its broadcast hours to its top five genres of Reality, Comedy, Drama, Movie, and News while GSN aired content of those genres in less than 3% of its airtime. WE tv offers programming in 10 different genres while virtually all of GSN’s programming is found in just two genres. .................................................11 2. The 2012 public {{** **}} statements of GSN’s senior executives affirm that it has been a Game Show network