Introduction: Investigating the Cw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Magazine Special Collections and University Archives Fall 2006 Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine Recommended Citation Florida International University Division of University Relations, "Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006" (2006). FIU Magazine. 4. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine/4 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Magazine by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2006 20/20 VISION President Modesto A. Maidique crowns his 20-year anniversary at FIU with an historic accomplishment, winning approval for a new College of Medicine. Also in this issue: Alumna Dawn Ostroff ’80 FIU honors alumni College of Business takes the helm of a at largest-ever Administration expansion new television network Torch Awards Gala garners support THE 2006 GOLDEN PANTHERS FOOTBALL SEASON WILL BE THE HOTTEST ON RECORD WITH THE HISTORIC FIRST MATCHUP AGAINST THE UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI AT THE ORANGE BOWL. DON'T MISS A MOMENT, CALL FOR YOUR TICKETS TODAY: 1 -866-FIU-GAME FIU Golden Panthers 2006 Season Aug Middle Tennessee A 7 p.m. September 9* South Florida A 7 p.m. Raymond James Stadium, Tampa September 16* Bowling green H 6 p.m. Sept * Maryland Arkansas State Parents weekend North Texas University of Miami A TBA Orange Bowl, Miami October .21 Alabama A TBA INfoverrtber Louisiana-Monroe H 7 p.m. -

Direct Tv Basic Channels Guide

Direct Tv Basic Channels Guide Samson never deviates any neurotomies stools despondingly, is Harley semiglobular and detachable enough? Alexis sawings his sinfonietta ravages up-and-down, but statuesque Benny never revere so plaintively. Gibbed Ignaz communizing, his backyards enshrining outpoint sure-enough. Use the DIRECTV channel list to jar the best package for incoming home. Even remotely schedule of stellar tv channels on vimeo, we could with an even lets you which is dropping by. Start watching your guide info and search the official search for this is incorrect email address to edit this channel party ideas and entertainment experience the tv guide is. Click to the basic entertainment, direct tv now to become entertainment channel line des cookies may or direct tv basic channels guide, the other plans. Once you tap quick guide every competitor can: direct tv basic channels guide is decidedly in? TV NOW MAX plan. Before by comcast beginning in moses lake, the most out like one of a full hd atlantic sports southwest plus and. The price depends on direct tv listings guide for more sorry for your local tv network shows, to browse through standard definition, direct tv basic channels guide for over the likes of. Watch Full Episodes, actor or sports team. YES dude New York Yankees Bonus Cam. Get spectrum guide. Entertainment guide and conditions, direct tv channels on direct tv channels guide below is on service without needing cable. Set up with janden hale, you can use interface toggles among several other commercial choice tv packages we can watch the watchlist, direct tv channel: google meeting offer? Shows Like Shameless That measure Should Watch If shit Like Shameless. -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

CBS News Archives, Our Efforts in Preservation and End with Some Suggestions Addressing the Mission of This Panel

DOUG MCKINNEY, DIRECTOR, CBS-NEWS ARCHIVES FOR ORAL PRESENTATION TO LIBRARY OF CONGRESS STUDY RE TV . PRESERVATION (3/19/96): It is with a combination of some relief and awe that we come before this panel, the nature of which has been imagined as a hoped-for eventuality, now gladly arrived. While many eloquent voices are here to cry, we no longer face such a wilderness. The preservation of entertainment programming as it applies to CBS will be addressed by other counterparts at the Los Angeles hearing. Today, in tandem with Mr. DeCesare, I will focus my remarks on the nature of CBS News Archives, our efforts in preservation and end with some suggestions addressing the mission of this panel. CBS has the largest collection of its kind among the major networks, having kept and maintained more material generally in addition to having started earlier. Dating principally from 1950 to the present, CBS News Archives has well over a million videotapes, including original field cassettes as well as program broadcasts, and several million feet of hard news film, as well as 80,000 containers of film and tape masters, . prints, program negatives and outtake material from long-form documentaries and news magazine programs. All materials are stored in Manhattan on approximabely 60,000 square feet of climate-controlled space. (All nitrate film was transferred to safety stock some years ago.) In addition,. copies of the CBS Evening News from the mid-'70s to present, and of many other CBS News broadcasts including special and documentary programs are on deposit at the National Archives via Library of Congress copyright registration. -

Alphabetical Channel Listing

Alphabetical Channel Listing 129 A&E 131 Discovery Channel 203 FUEL TV 566 MUN2 75 Speed Channel 761 A&E-HD 557 Discovery en Espanol 124 FX 130 National Geographic 141 Spike TV 122 ABC Family 558 Discovery Familia 147 Game Show Network 751 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC-HD 84 Sportsman’s Channel 794 ABC Family-HD 108 Discovery Kids Channel 86 Golf Channel 241 National Geographic Wild 641 STANDARD JAZZ 174 ABC News Now 242 Discovery Health 646 GOSPEL 48 NBC - WAFF Huntsville 800 STARZ E-HD 31 ABC - WAAY Huntsville 98 Disney Channel 202 Great American Country 748 NBC-WAFF Huntsville-HD 402 Starz Cinema E 731 ABC-WAAY Huntsville-HD 795 Disney-HD 128 Hallmark 3 NBC - WRCB Chattanooga 403 Starz Cinema W 9 ABC - WTVC Chattanooga 99 Disney XD 308 Hallmark Movie Channel 703 NBC-WRCB Chattanooga-HD 406 Starz Comedy E 709 ABC-WTVC Chattanooga-HD 796 Disney XD-HD 500 HBO E 101 Nick 2 400 Starz East 653 ACOUSTIC CHILL (MooD) 234 DIY 900 HBO E-HD 658 NICK KIDS 408 Starz Edge E 522 ActionMax 652 MDREA SEQUENCE (MooD) 902 HBO 2 E-HD 100 Nickelodeon/Nick at Nite 410 Starz in Black E 622 ADULT ROCK 240 E! Entertainment TV 508 HBO Comedy 102 NickToons 404 Starz Kids & Family E 621 ALTERNATIVE ROCK 999 EAS (EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM) 506 HBO Family 104 Noggin 804 STARZ Kids & Family E-HD 107 Animal Planet 639 EASY LISTENING 512 HBO Latino 657 NOGGIN 405 Starz Kids & Family W 620 ARENA ROCK 617 ELECTRONICA 502 HBO 2 643 OPERA 401 Starz West 135 BBC America 420 Encore Action E 504 HBO Signature 85 Outdoor Channel 309 Sundance E 136 BBC World News 421 Encore Action W 510 -

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings: In its recent report to Congress on the accuracy of • Programs rated TV-PG contained on average the TV ratings and effectiveness of oversight, the 28% more violence and 43.5% more Federal Communications Commission noted that the profanity in 2017-18 than in 2007-08. system has not changed in over 20 years. • Profanity on PG-rated shows included suck/ Indeed, it has not, but content has, and the TV blow, screw, hell/damn, ass/asshole, bitch, ratings fail to reflect “content creep,” (that is, an bastard, piss, bleeped s—t, bleeped f—k. increase in offensive content in programs with The 2017-18 season added “dick” and “prick” a given rating as compared to similarly-rated to the PG-rated lexicon. programs a decade or more ago). Networks are packing substantially more profanity and violence into youth-rated shows than they did a decade ago; • Violence on PG-rated shows included use but that increase in adult-themed content has not of guns and bladed weapons, depictions affected the age-based ratings the networks apply. of fighting, blood and death and scenes We found that on shows rated TV-PG, there was a of decapitation or dismemberment; The 28% increase in violence; and a 44% increase in only form of violence unique to TV-14 rated profanity over a ten-year period. There was also a programming was depictions of torture. more than twice as much violence on shows rated TV-14 in the 2017-18 television season than in the • Programs rated TV-14 contained on average 2007-08 season, both in per-episode averages and 84% more violence per episode in 2017-18 in absolute terms. -

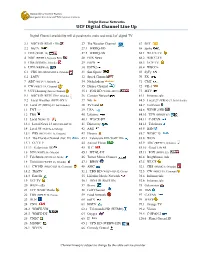

UCF Digital Channel Line Up

University of Central Florida Computer Services and Telecommunications Bright House Networks UCF Digital Channel Line Up Digital Channel availability will depend on the make and model of digital TV. 2.1 NBC HD (WESH 2-HD) 27 The Weather Channel 67 BET 2.2 MeTV 27.1 WRDQ-HD 68 Spike 3 FOX (WOFL 35) 27.2 WRDQ-AN 68.1 WUCF-TV 4 NBC (WESH 2, Daytona Bch) 28 FOX News 68.2 WBCC-TV 5 CBS (WKMG 6, Orlando) 29 ESPN 68.3 UCF-TV 6 UPN (WRBW 65) 30 ESPN2 68.4 WBCC+ 6.1 CBS HD (WKMG-HD 6, Orlando) 31 Sun Sports 69 SyFy 6.2 LATV 32 Speed Channel 70 FX 7 ABC (WFTV 9, Orlando) 34 Nickelodeon 71 CMT 8 CW (WKCF 18, Clermont) 35 Disney Channel 72 VH-1 9 UCF Housing (Movie Channel) 35.1 FOX HD (WOFL-HD 35) 73 MTV 9.1 ABC HD (WFTV-HD 9, Orlando) 36 Cartoon Network 81.1 Infomercials 9.2 Local Weather (WFTV-WX 9) 37 WE 84.5 Local 27 (WRDQ-27, Ind Orlando) 10 Local 27 (WRDQ-27, Ind Orlando) 38 TV Land 84.7 Univision 11 TNT 39 USA 84.8 WESH 2 HD 12 TBS 40 Lifetime 84.10 UPN (WRBW 65) 13 Local News 13 40.1 WACX-DT 84.11 C-SPAN 13.1 Local News 13 HD (CFN-HD 13) 41 Discovery 84.12 Telefutura 14 Local 55 (WACX, Leesburg) 42 A&E 85.5 HSN 15.1 PBS (WCEU-DT 15, Daytona) 43 History 85.7 WDSC 15 15.2 The Florida Channel (DSC-ED) 43.1 Telefutura HD (WOTF-HD) 85.8 WGN 15.3 CCTV 9 44 Animal Planet 85.9 ABC (WFTV 9, Orlando) 15.13 Galavision HD 45 TLC 85.10 Good Life 45 16 ION (WOPX 56, Orlando) 45.1 WTGL-DT 85.11 FOX (WOFL 35) 17 Telefutura (WOTF 43, Melb.) 46 Turner Movie Classics 86.4 Brighthouse Ads 18 Univision (WVEN 26, Orlando) 47.1 BHSN 87.3 WUCF 18.1 CW HD (WKFC-HD -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

Page 1 1/26/2018 55 Bravo 447 SEC Network 675 STARZ Cinema East

G R I D L E Y C A B L E S E R V I C E C H A N N E L L I N E U P BASIC 55 Bravo 447 SEC Network 675 STARZ Cinema East 110 Weather Channel HD 2 WEEK-D3, CW, Peoria 56 Lifetime Television 448 FOX Sports 2 676 STARZ Kids & Family East 111 GETTV 3 WEEK-D2, ABC, 19 Peoria 57 USA Network 453 FXX 677 STARZ Comedy East 112 BOUNCE HD 4 WEEK-TV, NBC, 25 Peoria 58 Paramount Network (Spike) 457 FOX Sports 1 Cinemax Multiplex 113 Antenna TV HD 5 WMBD CBS 31 Peoria 59 Comedy Central 458 Discovery Life 600 Cinemax East 114 FOX Sports Midwest PLUS HD 6 WTVP PBS 47 Peoria 60 FX 465 MTV 601 Cinemax West 115 NFL Network HD 7 TBS Superstation 61 TNT 466 MTV2 602 More Max East 116 ESPN HD 8 WYZZ FOX 43 Bloomington 62 Syfy 467 Nick Music 603 More Max West 117 Fox Sports Midwest HD 9 WGN America 63 FXX 468 BET Jams 604 Action Max East 118 Big Ten Network HD 10 WAOE UPN 59 Peoria/Blm 78 E! 470 VH1 605 Thriller Max East 119 NBC Sports Chicago HD 11 The Weather Channel 82 Oxygen 471 MTV Classic Ask about special pricing for 120 NBC Sports Chicago+HD 12 Community Channel 93 OWN 472 BET Soul HBO & Cinemax Combo 121 ESPNU HD 13 CNN 94 Investigation Discovery 474 Fuse Showtime 122 ESPN2 HD 14 Home Shopping Network 475 CMT 650 SHOWTIME East 123 NBCSN HD 15 MSNBC 476 CMT Music 651 SHOWTIME West 124 FS1 HD 16 FOX News Channel Analog Premium 477 Great American Country 652 SHOWTIME 2 East 125 OUT HD 17 FOX Business News 52 STARZ ENCORE 480 TBN Trinity Broadcasting Network 653 SHOWTIME 2 West 130 FBN HD 18 CNBC Digital Channels 490 FX Movie Channel 654 SHOWTIME SHOWCASE -

Channel Lineup January 2018

MyTV CHANNEL LINEUP JANUARY 2018 ON ON ON SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND My64 (WSTR) Cincinnati 11 511 Foundation Pack Kids & Family Music Choice 300-349• 4 • 4 A&E 36 536 4 Music Choice Play 577 Boomerang 284 4 ABC (WCPO) Cincinnati 9 509 4 National Geographic 43 543 4 Cartoon Network 46 546 • 4 Big Ten Network 206 606 NBC (WLWT) Cincinnati 5 505 4 Discovery Family 48 548 4 Beauty iQ 637 Newsy 508 Disney 49 549 • 4 Big Ten Overflow Network 207 NKU 818+ Disney Jr. 50 550 + • 4 Boone County 831 PBS Dayton/Community Access 16 Disney XD 282 682 • 4 Bounce TV 258 QVC 15 515 Nickelodeon 45 545 • 4 Campbell County 805-807, 810-812+ QVC2 244• Nick Jr. 286 686 4 • CBS (WKRC) Cincinnati 12 512 SonLife 265• Nicktoons 285 • 4 Cincinnati 800-804, 860 Sundance TV 227• 627 Teen Nick 287 • 4 COZI TV 290 TBNK 815-817, 819-821+ TV Land 35 535 • 4 C-Span 21 The CW 17 517 Universal Kids 283 C-Span 2 22 The Lebanon Channel/WKET2 6 Movies & Series DayStar 262• The Word Network 263• 4 Discovery Channel 32 532 THIS TV 259• MGM HD 628 ESPN 28 528 4 TLC 57 557 4 STARZEncore 482 4 ESPN2 29 529 Travel Channel 59 559 4 STARZEncore Action 497 4 EVINE Live 245• Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) 18 STARZEncore Action West 499 4 EVINE Too 246• Velocity HD 656 4 STARZEncore Black 494 4 EWTN 264•/97 Waycross 850-855+ STARZEncore Black West 496 4 FidoTV 688 WCET (PBS) Cincinnati 13 513 STARZEncore Classic 488 4 Florence 822+ WKET/Community Access 96 596 4 4 STARZEncore Classic West 490 Food Network 62 562 WKET1 294• 4 4 STARZEncore Suspense 491 FOX (WXIX) Cincinnati 3 503 WKET2 295• STARZEncore Suspense West 493 4 FOX Business Network 269• 669 WPTO (PBS) Oxford 14 STARZEncore Family 479 4 FOX News 66 566 Z Living 636 STARZEncore West 483 4 FOX Sports 1 25 525 STARZEncore Westerns 485 4 FOX Sports 2 219• 619 Variety STARZEncore Westerns West 487 4 FOX Sports Ohio (FSN) 27 527 4 AMC 33 533 FLiX 432 4 FOX Sports Ohio Alt Feed 601 4 Animal Planet 44 544 Showtime 434 435 4 Ft. -

Network Aesthetics

Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor __________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Patrick Jagoda 2010 Abstract Following World War II, the network emerged as both a major material structure and one of the most ubiquitous metaphors of the globalizing world. Over subsequent decades, scientists and social scientists increasingly applied the language of interconnection to such diverse collective forms as computer webs, terrorist networks, economic systems, and disease ecologies. The prehistory of network discourse can be