The Art of Divination in Indigenous America—A Comparison of Ancient Mexican and Modern Kuna Pictography Alessia Frassani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices

1 Multilingual Discourses Vol. 1.2 Spring 2014 Tanya Ball The Power of Death: Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices hrough an examination of Aztec death iconography in pre- and post-Conquest codices of the central valley of Mexico T (Borgia, Mendoza, Florentine, and Telleriano-Remensis), this paper will explore how attitudes towards the Aztec afterlife were linked to questions of hierarchical structure, ritual performance and the preservation of Aztec cosmovision. Particular attention will be paid to the representation of mummy bundles, sacrificial debt- payment and god-impersonator (ixiptla) sacrificial rituals. The scholarship of Alfredo López-Austin on Aztec world preservation through sacrifice will serve as a framework in this analysis of Aztec iconography on death. The transformation of pre-Hispanic traditions of representing death will be traced from these pre- to post-Conquest Mexican codices, in light of processes of guided syncretism as defined by Hugo G. Nutini and Diana Taylor’s work on the performative role that codices play in re-activating the past. These practices will help to reflect on the creation of the modern-day Mexican holiday of Día de los Muertos. Introduction An exploration of the representation of death in Mexica (popularly known as Aztec) pre- and post-Conquest Central Mexican codices is fascinating because it may reveal to us the persistence and transformation of Aztec attitudes towards death and the after-life, which in some cases still persist today in the Mexican holiday Día de Tanya Ball 2 los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. This tradition, which hails back to pre-Columbian times, occurs every November 1st and 2nd to coincide with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ day in the Christian calendar, and honours the spirits of the deceased. -

Oral Tradition 25.2

Oral Tradition, 25/2 (2010): 325-363 “Secret Language” in Oral and Graphic Form: Religious-Magic Discourse in Aztec Speeches and Manuscripts Katarzyna Mikulska Dąbrowska Introduction On the eve of the conquest, oral communication dominated Mesoamerican society, with systems similar to those defined by Walter Ong (1992 [1982]), Paul Zumthor (1983), and Albert Lord (1960 [2000]), although a written form did exist. Its limitations were partly due to the fact that it was used only by a limited group of people (Craveri 2004:29), and because the Mixtec and Nahua systems do not totally conform to a linear writing system.1 These forms of graphic communication are presented in pictographic manuscripts, commonly known as codices. The analysis of these sources represents an almost independent discipline, as they increasingly become an ever more important source for Mesoamerican history, religion, and anthropology. The methodology used to study them largely depends on how the scholar defines “writing.” Some apply the most rigid definition of a system based on the spoken language and reflecting its forms and/or structures (e.g., Coulmas 1996:xxvi), while others accept a broader definition of semasiographic systems that can transmit ideas independent of actual spoken language (yet function at the same logical level) and thus also constitute writing (e.g., Sampson 1985:26-31). The aim of this study is to analyze the linguistic “magical-religious” register of the Nahua people, designated as such because it was used for communication with the sacred realm. In this respect, it represents one of the “sacred languages,” as classified by Zumthor (1983:53). -

Quetzalcoatl, the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 11 Number 1 Article 3 7-31-2002 Quetzalcoatl, the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ Diane E. Wirth Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wirth, Diane E. (2002) "Quetzalcoatl, the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol11/iss1/3 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Quetzalcoatl, the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ Author(s) Diane E. Wirth Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/1 (2002): 4–15, 107. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Many scholars suggest that Quetzalcoatl of Mesoamerica (also known as the Feathered Serpent), the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ could all be the same being. By looking at ancient Mayan writings such as the Popol Vuh, this theory is further explored and developed. These ancient writings include several stories that coincide with the stories of Jesus Christ in the Bible, such as the creation and the resurrec- tion. The role that both Quetzalcoatl and the Maize God played in bringing maize to humankind is com- parable to Christ’s role in bringing the bread of life to humankind. Furthermore, Quetzalcoatl is said to have descended to the Underworld to perform a sacrifice strikingly similar to the atonement of Jesus Christ. -

The Devil and the Skirt an Iconographic Inquiry Into the Prehispanic Nature of the Tzitzimime

THE DEVIL AND THE SKIRT AN ICONOGRAPHIC INQUIRY INTO THE PREHISPANIC NATURE OF THE TZITZIMIME CECELIA F. KLEIN U.C.L.A. INTRODUCTION On folio 76r of the colonial Central Mexican painted manuscript Codex Magliabechiano, a large, round-eyed figure with disheveled black hair and skeletal head and limbs stares menacingly at the viewer (Fig. 1a). 1 Turned to face us, the image appears ready to burst from the cramped confines of its pictorial space, as if to reach out and grasp us with its sharp talons. Stunned by its gaping mouth and its protruding tongue in the form of an ancient Aztec sacrificial knife, viewers today may re- coil from the implication that the creature wants to eat them. This im- pression is confirmed by the cognate image on folio 46r of Codex Tudela (Fig. 1b). In the less artful Tudela version, it is blood rather than a stone knife that issues from the frightening figures mouth. The blood pours onto the ground in front of the figures outspread legs, where a snake dangles in the Magliabecchiano image. Whereas the Maglia- bechiano figure wears human hands in its ears, the ears of the Tudela figure have been adorned with bloody cloths. In both manuscripts, long assumed to present us with a window to the prehispanic past, a crest of paper banners embedded in the creatures unruly hair, together with a 1 This paper, which is dedicated to my friend and colleague Doris Heyden, evolved out of a talk presented at the 1993 symposium on Goddesses of the Western Hemisphere: Women and Power which was held at the M.H. -

The Rules of Construction of an Aztec Deity: Chalchiuhtlicue, the Goddess of Water

Ancient Mesoamerica, 31 (2020), 7–28 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2018 doi:10.1017/S0956536118000056 THE RULES OF CONSTRUCTION OF AN AZTEC DEITY: CHALCHIUHTLICUE, THE GODDESS OF WATER Danièle Dehouve Director of Research (emeritus), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique-Université Paris Ouest Nanterre, Maison Archéologie et Ethnologie, 21 allée de l’université, 92023 Nanterre Cedex, France Abstract This article seeks to contribute to the development of a method for analyzing the attributes of the gods of central Mexico in the manuscripts and the statuary from the time of the Spanish conquest. I focus on the Goddess of Water, Chalchiuhtlicue, “Jade Her Skirt.” The method consists of isolating the component designs of her array and grouping them in semantic groups. I begin by examining these designs and show that all of them were used in the notation of toponyms. These findings call into question the traditional separation between glyphs and icons. I next study the semantic groups and show that they consist of a series of culturally selected manifestations of water. Hence, it follows that the rules of composition of the goddess were grounded on a process of “definition by extension.” Thus, most of the semantic groups referred to different secondary names of the goddess, allowing us to think that they represented theonyms of a particular type. INTRODUCTION of “diagnostic insignia” assigned to each deity (Nicholson 1971: 408), the distinction between “determinant forms” and “isolated The numerous gods of central Mexico were identified by a principal forms” (Spranz 1973:27–28), or between “distinctive” (rasgos name and several secondary names, as well as by the ornaments distintivos) and “optional” traits (rasgos discrecionales; Mikulska encasing their anthropomorphic figure. -

Research for Book on Ancient Mexican Astronomy

FAMSI © 2001: Susan Milbrath Research for book on Ancient Mexican Astronomy Research Year: 2000 Culture: Aztec Chronology: Classic to Post Classic Location: México Sites: Various A two-semester leave allowed me time to travel extensively to study museum collections, archives, and library holdings related to my research for a book entitled Star Gods of Ancient México: Aztec Astronomy and the Mesoamerican World View. The book focuses on the role of astronomy in Aztec religion and the festival calendar, and how Aztec astronomy relates to the larger Mesoamerican worldview. With a $3,000 travel grant from the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI), I was able to complete an ambitious travel schedule to libraries and museum collections. I had originally intended to concentrate the travel portion of the project over a three-month period from May to July 2000, and write the book during the fall and spring semesters, 2000-2001. I was diverted from this plan from a number of offers to lecture and a month-long trip in January to Yucatán, a wonderful opportunity to do field work with transportation costs paid in exchange for informal lectures to the group of Colgate students. My travel for research funded by FAMSI took me to the following libraries and archives: University of Texas, UC Berkeley, UCLA, Tulane University, University of Pennsylvania, and Museo Nacional de Antropología in México City. In addition, I visited museum collections at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Fowler Museum of Cultural History in Los Angeles, the Hearst Museum of Anthropology at Berkeley, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Museo del Templo Mayor and the Museo Nacional de Anthropología e Historia in México City. -

UC Santa Barbara Revista: a Multi-Media, Multi-Genre E-Journal for Social Justice

UC Santa Barbara rEvista: A Multi-media, Multi-genre e-Journal for Social Justice Title Case Study for the Development of a Visual Grammar: Mayahuel and Maguey as Teotl in the Directional Tree Pages of the Codex Borgia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4gm205sx Journal rEvista: A Multi-media, Multi-genre e-Journal for Social Justice, 5(2) Author Lopez, Felicia Publication Date 2017 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Case Study for Development of a Visual Grammar: Mayahuel and Maguey as Teotl in the Directional Tree Pages of the Codex Borgia Felicia Rhapsody Lopez, University of California Santa Barbara “The books stand for an entire body of my current examination of the Codex indigenous knowledge, one that embraces Borgia, I seek to further the decolonial both science and philosophy.” – Elizabeth project of recovering Indigenous Hill Boone (2007:3) knowledge through methods that center Mesoamerican voices, docu- The results of the invasion and ments, and language.1 colonization of the Americas include Mesoamerican scribes created a wide not only widespread genocide, but also variety of texts (from historical, to the destruction of Indigenous texts and topographical, to ritual) containing culture. Today only 12 codices from maguey iconography, which draw upon Precontact Central Mexico remain. the cultural symbolism, metaphor, and Among these are a group of six, defined scientific understanding of the plant by their similarities in iconographic and of the teotl2 Mayahuel in order to style, content, and geographic region of provide a rich and layered meaning for origin, called the Borgia Group, so their Indigenous readers. -

Aztec Culture” P

Smith, “Aztec Culture” p. 1 AZTEC CULTURE: AN OVERVIEW By Dr. Michael E. Smith, Arizona State University, © 2006, Michael E. Smith This essay is based on several encyclopedia entries I have written over the past few years. One reason for posting this work on the internet is the poor quality of the entry for “Aztec” in the Wikipedia. Aztec culture flourished in the of the Aztec empire; as a result we have far highlands of central Mexico between the more information about the history of the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, AD. As the Mexica than about the other Aztec city-states. last in a series of complex urban civilizations Ritual almanacs such as the Codex Borgia and in Mesoamerica, the Aztecs adopted many the Codex Borbonicus were consulted by traits and institutions from their predecessors priests for use in rituals and divination. These such as the Maya and Teotihuacan. The Aztecs documents, rich in imagery of gods and sacred also devised many innovations, particularly in events, were structured around a second Aztec the realms of economics and politics. Aztec calendar, the 260-day ritual cycle. Tribute civilization was destroyed at its height by the records were used to record local payments to invasion of Spanish conquerors under lords and kings as well as the imperial tribute Hernando Cortés in 1519. The Aztec peoples, of the Mexica empire. The best-known Aztec who spoke the Nahuatl language, survived and codex is the Codex Mendoza, a composite intermarried with the Spaniards; today there document from 1541 with a history section are still over one million speakers of Nahuatl (depicting the conquests of the Mexica kings), in rural areas of central Mexico. -

Redalyc.Marriage Almanacs in the Mexican Divinatory Codices

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México Hill Boone, Elizabeth Marriage Almanacs in the Mexican Divinatory Codices Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXVIII, núm. 89, otoño, 2006, pp. 71-92 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36908906 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative ELIZABETH HILL BOONE tulane university Marriage Almanacs in the Mexican Divinatory Codices riting in 1541 from Tehuacan, Mexico, to his patron in Spain, the Franciscan friar Toribio de Motolinía reflected on the knowledge he Whad gained of Aztec customs and lifeways.1 Much of this knowledge, he said, came from the “ancient books” that the indigenous people had, books “written in symbols and pictures” rather than in letters, but efficacious nonethe- less. Motolinía divided the world of Aztec books into five genres, pertaining var- iously to the realms of history, religion and ritual, dreams and omens, and bap- tism and the naming of children, among other subjects. One particular genre, he noted — the fifth one — pertained to “the rites, ceremonies, and omens of the Indians relating to marriage.” Marriage was an extremely important institu- tion for the Aztecs and their neighbors. Through marriage, new households were created, families were joined, children were produced and raised, and political alliances were forged. -

GUARDIANS of IDOLATRY

GUARDIANS of IDOLATRY GODS, DEMONS, and PRIESTS in Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón’s Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions Viviana Díaz Balsera GUARDIANS of IDOLATRY GUARDIANS of IDOLATRY GODS, DEMONS, and PRIESTS in Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón’s Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions Viviana Díaz Balsera UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS : NORMAN Publication of this book is made possible through the generosity of Edith Kinney Gaylord. Parts of the introduction and chapter 2 in this book were previously published as “Nombres que conservan el mundo: los nahualtocaitl, el Tratado sobre idolatrías de Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón,” by Viviana Díaz Balsera, in Colonial Latin American Review 16.2 (2007), 159–78. Part of chapter 3 in this book was previously published as “Voicing Mesoamerican Identities on the Roads of Empire: Alarcón and the Nahualtocaitl in Seventeenth-Century Mexico,” by Viviana Díaz Balsera, in To Be Indio in Colonial Spanish America, edited by Mónica Díaz (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017), 169–90. Part of chapter 6 in this book was previously published as “Atando dioses y humanos: Cipactónal y la cura por adivinación en el Tratado sobre idolatrías de Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón,” by Viviana Díaz Balsera, in Estudios coloniales latinoamericanos en el siglo XXI: Nuevos itinerarios, edited by Stephanie Kirk (Pittsburgh: Instituto Internacional de Literatura Iberoamericana, Serie Nueva América, 2011), 321–49. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Name: Díaz Balsera, Viviana, 1957– author. Title: Guardians of idolatry : gods, demons, and priests in Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón’s treatise on the heathen superstitions / Viviana Díaz Balsera. Other titles: Gods, demons, and priests in Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón’s treatise on the heathen superstitions Description: First edition. -

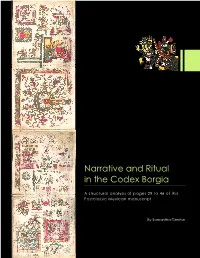

Narrative and Ritual in the Codex Borgia

Narrative and Ritual in the Codex Borgia A structural analysis of pages 29 to 46 of this Postclassic Mexican manuscript By Samantha Gerritse Narrative and Ritual in the Codex Borgia A structural analysis of pages 29 to 46 of this Postclassic Mexican manuscript Samantha Gerritse Course: RMA thesis, 1046WTY, final draft Student number: 0814121 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. M.E.R.G.N. Jansen Specialization: Religion and Society Institution: Faculty of Archaeology Place and date: Delft, June 2013 Contents. Acknowledgements p. 5 I. 1. Introduction p. 6 1.1 General research problem p. 6 1.2 The Codex Borgia p. 7 1.3 Problems with pages 29 to 46 of the Codex Borgia p. 10 1.2 Research aims and questions p. 11 2. Mesoamerican Religion p. 13 2.1 Worldview p. 13 2.2 Calendars p. 17 2.3 Priests and public rituals p. 19 2.4 Divination p. 21 3. Theoretical Framework p. 24 3.1 Interpretation by analogy p. 24 3.2 Interpretation by narratology p. 27 4. Methodology p. 32 4.1 Analysis of the interpretations p. 32 4.2 Analysis through narratology p. 33 II. 5. Iconographical interpretations of pages 29 to 46 p. 36 5.1 An overview p. 36 5.1.1 Fábrega (1899) p. 38 5.1.2 Seler (1906; 1963) p. 41 5.1.3 Milbrath (1989) p. 49 5.1.4 Nowotny (1961; 1976; 2005) p. 55 5.1.5 Anders, Jansen, and Reyes García (1993a) p. 61 5.1.6 Byland (1993) p. 70 5.1.7 Boone (2007) p. -

The Deity As a Mosaic: Images of the God Xipe Totec in Divinatory Codices from Central Mesoamerica

Ancient Mesoamerica, page 1 of 27, 2021 Copyright © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/S0956536120000553 THE DEITY AS A MOSAIC: IMAGES OF THE GOD XIPE TOTEC IN DIVINATORY CODICES FROM CENTRAL MESOAMERICA Katarzyna Mikulska Institute of Iberian and Iberoamerican Studies, University of Warsaw, ul. Krakowskie Przedmies´cie 26/28, 00-927 Warsaw, Poland Abstract In this article I argue that the graphic images of the gods in the divinatory codices are composed of signs of different semantic values which encode particular properties. All of them contribute to creating the identity of the god. However, these graphic elements are not only shared by different deities, but even differ between representations of the same god. Analyzing the graphic images of Xipe Totec, one of the best-studied deities and one of the oldest in Mesoamerica, I elaborate a hypothesis that the images of the gods in the divinatory codices were perceived by their authors as a mosaic of different properties, which at the same time were dynamic. Consequently, there was not even one “prototypical” representation of a single god, since possibly the identity of a god was defined precisely when composing his/her image with particular graphic signs, thus crystallizing some of his/her multiple properties, important at this precise moment.