Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto's Queer Futurity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Power : Tactiques Artistiques Et Politiques De L’Identité En Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc

Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc To cite this version: Emilie Blanc. Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990). Art et histoire de l’art. Université Rennes 2, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017REN20040. tel-01677735 HAL Id: tel-01677735 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01677735 Submitted on 8 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE / UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université européenne de Bretagne Emilie Blanc pour obtenir le titre de Préparée au sein de l’unité : EA 1279 – Histoire et DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 Mention : Histoire et critique des arts critique des arts Ecole doctorale Arts Lettres Langues Thèse soutenue le 15 novembre 2017 Art Power : tactiques devant le jury composé de : Richard CÁNDIDA SMITH artistiques et politiques Professeur, Université de Californie à Berkeley Gildas LE VOGUER de l’identité en Californie Professeur, Université Rennes 2 Caroline ROLLAND-DIAMOND (1966-1990) Professeure, Université Paris Nanterre / rapporteure Evelyne TOUSSAINT Professeure, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès / rapporteure Elvan ZABUNYAN Volume 1 Professeure, Université Rennes 2 / Directrice de thèse Giovanna ZAPPERI Professeure, Université François Rabelais - Tours Blanc, Emilie. -

(October 1979)Broadsheet-1979-073

broadsheetnew Zealand’s feminist magazine 90 cents S - marnr will "ave to be She: A fool. of love anc • Exposê by stroppy stripper — what it’s like on the job • Women’s Rights Groups - how effective are they? • Broadsheet puts psychology on the couch. Registered at the GPO, Wellington as a magazine. FRONTING UP Broadsheet Office Requests for Information Broadsheet by displaying a Broad is at: We frequently receive requests sheet sticker on your car. A 1st floor, Colebrooks Building, from readers for information on a stamped addressed envelope sent 93 Anzac Ave, Auckland. vast range of subjects. How much a with your request will help us save Office hours: 9-3, Mon-Fri. sub costs; what local feminist money. Phone number: 794-751. groups are there in an area; health Our box number is: problems. We would like people, Enveloping of November issue P.O. Box 5799, Wellesley St, when writing to us in future, to en will be on: Auckland, New Zealand. close a stamped addressed envelope Saturday 27th October for the returning of information. We at the Broadsheet address above. simply can’t afford to bear this cost Any hours you can donate between Subscription increases any longer. 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. would be grate Because we were already making fully accepted. Just turn up at the so little on each copy of Broadsheet Free back issues office, and bring kids too. Numbers we are unable to absorb the in It is our policy to give bundles of were thin at the enveloping of the creased postal charges, which by back issues away to readers who September issue. -

A Finding Aid to the Woman's Building Records, 1970-1992, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Woman's Building Records, 1970-1992, in the Archives of American Art Diana L. Shenk and Rihoko Ueno Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Getty Foundation. Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by The Walton Family Foundation and Joyce F. Menschel, Vital Projects Fund, Inc. August 2007 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Administrative Files, circa 1970-1991....................................................... 5 Series 2: Education Programs, -

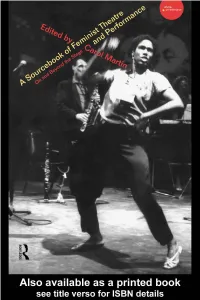

A Sourcebook on Feminist Theatre and Performance: on and Beyond the Stage/Edited by Carol Martin; with an Introduction by Jill Dolan

A SOURCEBOOK OF FEMINIST THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE A Sourcebook of Feminist Theatre and Performance brings together key articles first published in The Drama Review (TDR), to provide an intriguing overview of the development of feminist theatre and performance. Divided into the categories of “history,” “theory,” “interviews,” and “texts,” the materials in this collection allow the reader to consider the developments of feminist theatre through a variety of perspectives. This book contains the seminal texts of theorists such as Elin Diamond, Peggy Phelan, and Lynda Hart, interviews with performance artists including Anna Deveare Smith and Robbie McCauley, and the full performance texts of Holly Hughes’ Dress Suits to Hire and Karen Finley’s The Constant State of Desire. The outstanding diversity of this collection makes for an invaluable sourcebook. A Sourcebook of Feminist Theatre and Performance will be read by students and practitioners of theatre and performance, as well as those interested in the performance of sexualities and genders. Carol Martin is Assistant Professor of Drama at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. WORLDS OF PERFORMANCE What is a “performance”? Where does it take place? Who are the participants? Not so long ago these were settled questions, but today such orthodox answers are unsatisfactory, misleading, and limiting. “Performance” as a theoretical category and as a practice has expanded explosively. It now comprises a panoply of genres ranging from play, to popular entertainments, to theatre, dance, and music, to secular and religious rituals, to “performance in everyday life,” to intercultural experiments, and more. For nearly forty years, The Drama Review (TDR), the journal of performance studies, has been at the cutting edge of exploring these questions. -

Lesbians and Gay Men Were Tracked Down

ffiMU,1 I I ~ Restrained, Comic Robin Tyler Costanza Spying On .Jesus Freaks Resigns Teachers to Class or to Court? ~'EsaIAN PUBLICATlON,·WRITTEN BY AND FOR TH.E RISING TIDE OF wo.. APATHY IS A KILLER In Nazi Germany. lesbians and gay men were tracked down. arrested and marked with pink triangles. In Cetitornie. the Briggs tnitietive (Proposition 6) would ioenutv homosexuals and their supporters and evict them from teacher. teacher's euie. counselor and administrative positions In the public schools. In Nazi Germany. the first major book burning was the library of homosexual advocate Magnus Hirschfield's Institute of Social Science. In Cetiiornie. wittiin the last two months. over 20 businesses and homes of gay leaders have been firebombed. In Nazi Germany. over 220.000 gay men and women were executed In the ovens In San Francisco. a young gay man was shot and «itted In the steet: and In Tucson. AT/zona. a judge sentenced four convicted killers of a young homosexual to SIX months probetion and praised them for their service to the commurutv, Decent Germans did not believe that the holocaust was happening during the thirties What do you betieve today In the seventies? BRIGGS CAN BE DEFEATED The apathetic response of many members of the community IS the greatest ally of the Briggs Initiative. The tactics of pro-Briggs supporters are desrqned to scare us. to keep us quiet. and thus allow their victory on November 7th A recent survey has shown that Proposition 6 can be defeated If everyone who cares takes a minimum of action New AGE is ready to act now' WITH YOUR SUPPORT New AGE IS raising money for a major campaign being conducted to educate Caufor nias voters about the serious consequences of Proposition 6. -

CHANGING the EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING the EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP in the VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents

CHANGING THE EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING THE EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN THE VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents 6 Acknowledgments 7 Preface Linda Nochlin This publication is a project of the New York Communications Committee. 8 Statement Lila Harnett Copyright ©2005 by ArtTable, Inc. 9 Statement All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted Diane B. Frankel by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. 11 Setting the Stage Published by ArtTable, Inc. Judith K. Brodsky Barbara Cavaliere, Managing Editor Renée Skuba, Designer Paul J. Weinstein Quality Printing, Inc., NY, Printer 29 “Those Fantastic Visionaries” Eleanor Munro ArtTable, Inc. 37 Highlights: 1980–2005 270 Lafayette Street, Suite 608 New York, NY 10012 Tel: (212) 343-1430 [email protected] www.arttable.org 94 Selection of Books HE WOMEN OF ARTTABLE ARE CELEBRATING a joyous twenty-fifth anniversary Acknowledgments Preface together. Together, the members can look back on years of consistent progress HE INITIAL IMPETUS FOR THIS BOOK was ArtTable’s 25th Anniversary. The approaching milestone set T and achievement, gained through the cooperative efforts of all of them. The us to thinking about the organization’s history. Was there a story to tell beyond the mere fact of organization started with twelve members in 1980, after the Women’s Art Movement had Tsustaining a quarter of a century, a story beyond survival and self-congratulation? As we rifled already achieved certain successes, mainly in the realm of women artists, who were through old files and forgotten photographs, recalling the organization’s twenty-five years of professional showing more widely and effectively, and in that of feminist art historians, who had networking and the remarkable women involved in it, a larger picture emerged. -

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012 Jan 23)

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012_Jan_23) GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITION Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011–January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design Introduction “Doin’ It in Public” documents a radical and fruitful period of art made by women at the Woman’s Building—a place described by Sondra Hale as “the first independent feminist cultural institution in the world.” The exhibition, two‐volume publication, website, video herstories, timeline, bibliography, performances, and educational programming offer accounts of the collaborations, performances, and courses conceived and conducted at the Woman’s Building (WB) and reflect on the nonprofit organization’s significant impact on the development of art and literature in Los Angeles between 1973 and 1991. The WB was founded in downtown Los Angeles in fall 1973 by artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as a public center for women’s culture with art galleries, classrooms, workshops, performance spaces, bookstore, travel agency, and café. At the time, it was described in promotional materials as “a special place where women can learn, work, explore, develop their own point of view and share it with everyone. Women of every age, race, economic group, lifestyle and sexuality are welcome. Women are invited to express themselves freely both verbally and visually to other women and the whole community.” When we first conceived of “Doin’ It in Public,” we wanted to incorporate the principles of feminist art education into our process. -

A Feminist Inheritance? Questions of Subjectivity and Ambivalence in Paul Mccarthy, Mike Kelley and Robert Gober

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 A Feminist Inheritance? Questions of Subjectivity and Ambivalence in Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelley and Robert Gober Marisa White-Hartman Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/334 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A FEMINIST INHERITANCE? QUESTIONS OF SUBJECTIVITY AND AMBIVALENCE IN PAUL MCCARTHY, MIKE KELLEY AND ROBERT GOBER by Marisa White-Hartman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 MARISA WHITE-HARTMAN All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dr. Anna Chave ––––––––––––––––––– Date Chair of Examining Committee Dr. Claire Bishop Date Executive Officer Dr. Mona Hadler Dr. Siona Wilson Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract A FEMINIST INHERITANCE? QUESTIONS OF SUBJECTIVITY AND AMBIVALENCE IN PAUL MCCARTHY, MIKE KELLEY AND ROBERT GOBER by Marisa White-Hartman Adviser: Professor Anna Chave This dissertation assesses the impact of feminist art of the 1970s on specific projects by three male artists: Paul McCarthy’s performance Sailor’s Meat (1975), Mike Kelley’s installation Half a Man (1989) and Robert Gober’s 1989 installation at the Paula Cooper Gallery. -

Working Papers of the WSMALA Project

UCLA Working Papers of the WSMALA Project Title Timeline for WSMALA Women and the Arts in Los Angeles 1960-1999 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sn7x6xd Author UCLA Center for the Study of Women Publication Date 2012-01-25 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Protest to Policy: Women’s Social Movement Activities in Los Angeles, 1960-1999 UCLA Center For the Study of Women Timeline for WSMALA Women and the Arts in Los Angeles 1960-1999 “From Protest to Policy: Women’s Social Movement Activities in Los Angeles, 1960-1999,” a multi-year research project by the UCLA Center for the Study of Women examined the how grassroots advocacy has shaped gender-related public policy in the arts, employment, healthcare, and higher education through an analysis of local women’s groups in Los Angeles between 1960 and 1999. During this period, women’s community groups organized around gender-based problems their members encountered in their lives, their families, and their neighborhoods. The following timeline represents the key events in the development of the feminist arts movement in Los Angeles from 1960-1999. 1960 Founding of Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Inc. (TLW) - Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Inc. was founded in Los Angeles by June Wayne. 1967 Recorded Images / Dimensional Media Exhibition - Dextra Frankel curated the Recorded Images / Dimensional Media exhibition at California State College, Fullerton October 20 – November 12. While selecting artworks for this show, Frankel visited the studio of then little-known artist, Judy Chicago, and decided to feature her art in the exhibition. -

The 1978 “A Lesbian Show” Exhibition: the Politics of Queer Organizing Around the Arts and the Fight for Visibility in American Cultural Memory

The 1978 “A Lesbian Show” Exhibition: The Politics of Queer Organizing around the Arts and the Fight for Visibility in American Cultural Memory AMST 350: Fall „10 Professor Paul Fisher December 20, 2010 By Anna J. Weick 1 Introduction “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting".1 -Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting Our history is our lifeblood. We look to the past to create ourselves, affirm our beliefs, and to legitimize our dreams and ambitions. With a historical erasure of real human identities, individuals in society struggle against the constant onslaught of bigotry with no stories of past success or positive expression. Gay history has been systematically ignored, repressed, and forgotten by American society. In particular, a historical memory of GLBTQ arts remains non-existent. Art by women, especially by queer women, has been deemed unimportant, self-involved, child- like, without skill, over-emotional, silly, trivial, ugly, passé, but it has never been truly legitimized by society or by our historical memory. A hostility towards the memory of GLBTQ art history and support for lesbian and gay art undermines aims of queer liberation. Queer Americans deserve, as do women, people of color and all those oppressed by the military-industrial complexes controlling the resources and people of the world, the dignity of accurate historical representation and a legitimization of their identities. The acknowledgement of Queer history is integral to and intimately connected to social equality. When people blindly believe that the historical record is a collection of apolitical facts, dangerous assumptions are upheld, and movements towards a forward-thinking, diverse and accepting, peace-seeking society are threatened. -

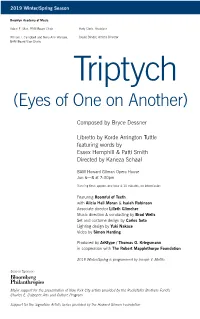

Triptych (Eyes of One on Another)

2019 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, BAM Board Chair Katy Clark, President William I. Campbell and Nora Ann Wallace, David Binder, Artistic Director BAM Board Vice Chairs Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by Korde Arrington Tuttle featuring words by Essex Hemphill & Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Jun 6—8 at 7:30pm Running time: approx. one hour & 10 minutes, no intermission Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran & Isaiah Robinson Associate director Lilleth Glimcher Music direction & conducting by Brad Wells Set and costume design by Carlos Soto Lighting design by Yuki Nakase Video by Simon Harding Produced by ArKtype / Thomas O. Kriegsmann in cooperation with The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 2019 Winter/Spring is programmed by Joseph V. Melillo. Season Sponsor: Major support for the presentation of New York City artists provided by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund’s Charles E. Culpeper Arts and Culture Program Support for the Signature Artists Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) Photo: Maria Baranova Contributing choreographer & performer Martell Ruffin Sound design by Damon Lange & Dylan Goodhue / nomadsound.net Production management William Knapp Dramaturgy by Talvin Wilks & Christopher Myers Managing producer ArKtype, J.J. El-Far Associate music director William Brittelle Associate lighting designer Valentina Migoulia Associate video designer Moe Shahrooz Production stage manager -

American Art: Lesbian, Post-Stonewall by Carla Williams

American Art: Lesbian, Post-Stonewall by Carla Williams Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Since Stonewall, lesbian artists in America, from installation artists to filmmakers and photographers to performance artists and painters, have become increasingly diverse and visible. Lesbians in the 1950s and 1960s benefited from both the feminist and the civil rights movements. Within the feminist movement emerged lesbian feminism, which gave rise to groups and experiences that galvanized the lesbian movement and gave many middle-class women the freedom in which to "come out" and embrace their sexuality. During this time, however, there were few venues and outlets for women's art, let alone lesbian art. One exception was The Ladder, the newsletter from 1956 until 1972 of the San Francisco-based Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the first lesbian rights organization, which regularly included artwork. The 1960s: Feminism and Abstraction Explicitly "lesbian" imagery did not emerge until the 1960s. The reasons for this are varied. Many lesbians shied away from sexual content for fear that explicit depictions of their sexuality would be misunderstood within a patriarchal, heterosexual society that was unable or unwilling to understand the nature of those images. Consequently, some lesbian artists made work with "ghetto content"--imagery that was understood only within the community. This strategy made it less likely for their work to be welcomed into a mainstream dialogue. As the feminist and civil rights movements progressed and women artists persisted, woman-based content began to emerge in the visual arts. The ideas that art might validate women's lives, that previously devalued craft traditions were significant, and that women's bodies were biological vessels of creation and change--these were not concepts that had been previously welcome in the canon, but they increasingly became the impetus for women's art.