Otherwise Imagining Queer Feminist Art Histories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto's Queer Futurity

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Jenni Sorkin, “Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto’s Queer Futurity,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926 /24716839.11411. Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto’s Queer Futurity Jenni Sorkin, Associate Professor, University of California, Santa Barbara Tina Takemoto’s experimental films are infused with a historical consciousness that invokes the queer gaps within the state-sanctioned record of Asian American history. This essay examines Takemoto’s semi-narrative experimental film, Looking for Jiro (fig. 1), which offers complex encounters of queer futurity, remaking historical gaps into interstitial spaces that invite and establish queer existence through both imaginative and direct traces of representation. Its primary subject, Jiro Onuma (1904–1990), is a gay, Japanese-born, American man who was imprisoned at Topaz War Relocation Center in Millard County, Utah, during the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans by the United States government during World War II.1 Takemoto’s title, Looking for Jiro, alludes to Isaac Julien’s lyrical black-and-white 1989 film, Looking for Langston, which is a pioneering postmodern vision of queer futurity, reenvisioning the sophisticated, homosocial world of the Harlem Renaissance and its sexual and creative possibilities for writers such as poet Langston Hughes (1902–1967). Fig. 1. Tina Takemoto, film still from Looking for Jiro, 2011 Over a five-year period, Takemoto developed a speculative -

Art Power : Tactiques Artistiques Et Politiques De L’Identité En Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc

Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc To cite this version: Emilie Blanc. Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990). Art et histoire de l’art. Université Rennes 2, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017REN20040. tel-01677735 HAL Id: tel-01677735 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01677735 Submitted on 8 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE / UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université européenne de Bretagne Emilie Blanc pour obtenir le titre de Préparée au sein de l’unité : EA 1279 – Histoire et DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 Mention : Histoire et critique des arts critique des arts Ecole doctorale Arts Lettres Langues Thèse soutenue le 15 novembre 2017 Art Power : tactiques devant le jury composé de : Richard CÁNDIDA SMITH artistiques et politiques Professeur, Université de Californie à Berkeley Gildas LE VOGUER de l’identité en Californie Professeur, Université Rennes 2 Caroline ROLLAND-DIAMOND (1966-1990) Professeure, Université Paris Nanterre / rapporteure Evelyne TOUSSAINT Professeure, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès / rapporteure Elvan ZABUNYAN Volume 1 Professeure, Université Rennes 2 / Directrice de thèse Giovanna ZAPPERI Professeure, Université François Rabelais - Tours Blanc, Emilie. -

AMELIA G. JONES Robert A

Last updated October 23, 2015 AMELIA G. JONES Robert A. Day Professor of Art & Design Vice Dean of Critical Studies Roski School of Art and Design University of Southern California 850 West 37th Street, Watt Hall 117B Los Angeles, CA 90089 USA m: 213-393-0545 [email protected], [email protected] EDUCATION: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES. Ph.D., Art History, June 1991. Specialty in modernism, contemporary art, film, and feminist theory; minor in critical theory. Dissertation: “The Fashion(ing) of Duchamp: Authorship, Gender, Postmodernism.” UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA, Philadelphia. M.A., Art History, 1987. Specialty in modern & contemporary art; history of photography. Thesis: “Man Ray's Photographic Nudes.” HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge. A.B., Magna Cum Laude in Art History, 1983. Honors thesis on American Impressionism. EMPLOYMENT: 2014 (August)- UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, Roski School of Art and Design, Los Angeles. Robert A. Day Professor of Art & Design and Vice Dean of Critical Studies. 2010-2014 McGILL UNIVERSITY, Art History & Communication Studies (AHCS) Department. Professor and Grierson Chair in Visual Culture. 2010-2014 Graduate Program Director for Art History (2010-13) and for AHCS (2013ff). 2003-2010 UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER, Art History & Visual Studies. Professor and Pilkington Chair. 2004-2006 Subject Head (Department Chair). 2007-2009 Postgraduate Coordinator (Graduate Program Director). 1991-2003 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, RIVERSIDE, Department of Art History. 1999ff: Professor of Twentieth-Century Art and Theory. 1993-2003 Graduate Program Director for Art History. 1990-1991 ART CENTER COLLEGE OF DESIGN, Pasadena. Instructor and Adviser. Designed and taught two graduate seminars: Contemporary Art; Feminism and Visual Practice. -

The Body and Technology Author(S): Amelia Jones, Geoffrey Batchen

The Body and Technology Author(s): Amelia Jones, Geoffrey Batchen, Ken Gonzales-Day, Peggy Phelan, Christine Ross, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Roberto Sifuentes, Matthew Finch Source: Art Journal, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 20-39 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778043 Accessed: 06/04/2009 10:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Art Journal. http://www.jstor.org Whether overtly or not, all visual culture plumbs the complex and profound intersections among visuality, embodiment, and the logics of mechanical, indus- trial, or cybernetic systems. -

'I Write Four Times….': a Tribute to the Work and Teaching of Donald Preziosi

‘I write four times….’: A tribute to the work and teaching of Donald Preziosi Amelia Jones ‘I write four times here, around painting.’ So states Jacques Derrida in section four of the first chapter, ‘Passe-Partout,’ of his book Truth in Painting, published in 1978 in French and in 1987 in English (translated brilliantly by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod). At first I had remembered this (strongly) as the first sentence of Truth in Painting. But in fact the first sentence of the book, which is also the first sentence of ‘Passe-Partout,’ reads as follows: ‘Someone, not me comes and says the words: “I am interested in the idiom in painting”.’ Derrida goes on, on the second page, to remind us of where the phrase ‘truth in painting’ comes from. It is ‘signed by Cézanne,’ who wrote to his fellow painter and friend Emile Bernard in 1905, ‘I OWE YOU THE TRUTH IN PAINTING AND I WILL TELL IT TO YOU.’ All of these sentences, but particularly ‘I write four times here, around painting,’ have stayed fresh in my mind for these almost thirty years, along with the last sentence of ‘Passe-Partout’ (one of my favorites in all poststructuralist theory): ‘The internal edges of a passe-partout are often beveled.’1 Four times. The sides of a frame, which signal the ‘inside’ of the work of art (its essence) by purporting to divide it from the ‘outside’ (the ‘parergonal,’ all that is extrinsic to its essential nature as art). Such is the grounding of aesthetics, which continues to inform our beliefs about this stuff we call ‘art.’ The four chapters of Truth in Painting after the prolegomenous “Passe-Partout”—1) ‘Parergon’; 2) ‘+R (Into the Bargain)’; 3) ‘Cartouches’; 4) ‘Restitutions’—parallel this ‘writing four times,’ and mimic the four sides of a frame. -

(October 1979)Broadsheet-1979-073

broadsheetnew Zealand’s feminist magazine 90 cents S - marnr will "ave to be She: A fool. of love anc • Exposê by stroppy stripper — what it’s like on the job • Women’s Rights Groups - how effective are they? • Broadsheet puts psychology on the couch. Registered at the GPO, Wellington as a magazine. FRONTING UP Broadsheet Office Requests for Information Broadsheet by displaying a Broad is at: We frequently receive requests sheet sticker on your car. A 1st floor, Colebrooks Building, from readers for information on a stamped addressed envelope sent 93 Anzac Ave, Auckland. vast range of subjects. How much a with your request will help us save Office hours: 9-3, Mon-Fri. sub costs; what local feminist money. Phone number: 794-751. groups are there in an area; health Our box number is: problems. We would like people, Enveloping of November issue P.O. Box 5799, Wellesley St, when writing to us in future, to en will be on: Auckland, New Zealand. close a stamped addressed envelope Saturday 27th October for the returning of information. We at the Broadsheet address above. simply can’t afford to bear this cost Any hours you can donate between Subscription increases any longer. 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. would be grate Because we were already making fully accepted. Just turn up at the so little on each copy of Broadsheet Free back issues office, and bring kids too. Numbers we are unable to absorb the in It is our policy to give bundles of were thin at the enveloping of the creased postal charges, which by back issues away to readers who September issue. -

A Finding Aid to the Woman's Building Records, 1970-1992, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Woman's Building Records, 1970-1992, in the Archives of American Art Diana L. Shenk and Rihoko Ueno Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Getty Foundation. Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by The Walton Family Foundation and Joyce F. Menschel, Vital Projects Fund, Inc. August 2007 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Administrative Files, circa 1970-1991....................................................... 5 Series 2: Education Programs, -

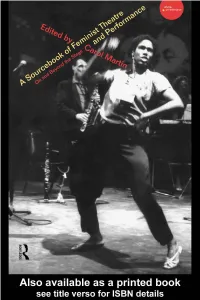

A Sourcebook on Feminist Theatre and Performance: on and Beyond the Stage/Edited by Carol Martin; with an Introduction by Jill Dolan

A SOURCEBOOK OF FEMINIST THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE A Sourcebook of Feminist Theatre and Performance brings together key articles first published in The Drama Review (TDR), to provide an intriguing overview of the development of feminist theatre and performance. Divided into the categories of “history,” “theory,” “interviews,” and “texts,” the materials in this collection allow the reader to consider the developments of feminist theatre through a variety of perspectives. This book contains the seminal texts of theorists such as Elin Diamond, Peggy Phelan, and Lynda Hart, interviews with performance artists including Anna Deveare Smith and Robbie McCauley, and the full performance texts of Holly Hughes’ Dress Suits to Hire and Karen Finley’s The Constant State of Desire. The outstanding diversity of this collection makes for an invaluable sourcebook. A Sourcebook of Feminist Theatre and Performance will be read by students and practitioners of theatre and performance, as well as those interested in the performance of sexualities and genders. Carol Martin is Assistant Professor of Drama at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. WORLDS OF PERFORMANCE What is a “performance”? Where does it take place? Who are the participants? Not so long ago these were settled questions, but today such orthodox answers are unsatisfactory, misleading, and limiting. “Performance” as a theoretical category and as a practice has expanded explosively. It now comprises a panoply of genres ranging from play, to popular entertainments, to theatre, dance, and music, to secular and religious rituals, to “performance in everyday life,” to intercultural experiments, and more. For nearly forty years, The Drama Review (TDR), the journal of performance studies, has been at the cutting edge of exploring these questions. -

ARHS 3358 – Gender and Sexuality in Modern and Contemporary Art

ARHS 3358 – Gender and Sexuality in Modern and Contemporary Art Dr. Anna Lovatt, [email protected] May Term 2018 (Thursday May 17 – Friday June 1) 11am to 1pm and 2pm to 4pm Room TBD Catherine Opie, Being and Having, 1991 Course Outline: Questions of gender and sexuality are central to our understanding of identity, community, self-expression and creativity. They have therefore been of vital interest to modern and contemporary artists. This course demonstrates how theories of gender and sexuality from a variety of disciplines can contribute to our knowledge of the production and reception of works of art. We will consider how artists have represented, performed and theorized gender and sexuality in their work. The gendering of the art historical canon will be another key concern, prompting us to look beyond the dominant narratives of modern and contemporary art to previously marginalized practices. Finally, we will consider the role of the viewer in the reception of art and how the act of looking is inflected by gender and sexuality. Instructor’s Biography: Dr. Anna Lovatt received her PhD from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London in 2005. Her research focuses on post-Minimal and Conceptual art of the 1960s and she has published extensively in this area. Dr. Lovatt joined SMU in 2014 as Scholar in Residence in the Department of Art History, having previously been Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Manchester, U.K. University Curriculum Requirements: 2 This course fulfills UC Foundations: Ways of Knowing Student Learning Outcomes: 1. Students will demonstrate knowledge of more than one disciplinary practice. -

Lesbians and Gay Men Were Tracked Down

ffiMU,1 I I ~ Restrained, Comic Robin Tyler Costanza Spying On .Jesus Freaks Resigns Teachers to Class or to Court? ~'EsaIAN PUBLICATlON,·WRITTEN BY AND FOR TH.E RISING TIDE OF wo.. APATHY IS A KILLER In Nazi Germany. lesbians and gay men were tracked down. arrested and marked with pink triangles. In Cetitornie. the Briggs tnitietive (Proposition 6) would ioenutv homosexuals and their supporters and evict them from teacher. teacher's euie. counselor and administrative positions In the public schools. In Nazi Germany. the first major book burning was the library of homosexual advocate Magnus Hirschfield's Institute of Social Science. In Cetiiornie. wittiin the last two months. over 20 businesses and homes of gay leaders have been firebombed. In Nazi Germany. over 220.000 gay men and women were executed In the ovens In San Francisco. a young gay man was shot and «itted In the steet: and In Tucson. AT/zona. a judge sentenced four convicted killers of a young homosexual to SIX months probetion and praised them for their service to the commurutv, Decent Germans did not believe that the holocaust was happening during the thirties What do you betieve today In the seventies? BRIGGS CAN BE DEFEATED The apathetic response of many members of the community IS the greatest ally of the Briggs Initiative. The tactics of pro-Briggs supporters are desrqned to scare us. to keep us quiet. and thus allow their victory on November 7th A recent survey has shown that Proposition 6 can be defeated If everyone who cares takes a minimum of action New AGE is ready to act now' WITH YOUR SUPPORT New AGE IS raising money for a major campaign being conducted to educate Caufor nias voters about the serious consequences of Proposition 6. -

AMELIA JONES “'Women' in Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie”

AMELIA JONES “’Women’ in Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie” From Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, Women in Dada:Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998): 142-172 In his 1918 Dada manifesto, Tristan Tzara stated the sources of “Dadaist Disgust”: “Morality is an injection of chocolate into the veins of all men....I proclaim the opposition of all cosmic faculties to [sentimentality,] this gonorrhea of a putrid sun issued from the factories of philosophical thought.... Every product of disgust capable of becoming a negation of the family is Dada.”1 The dadaists were antagonistic toward what they perceived as the loss of European cultural vitality (through the “putrid sun” of sentimentality in prewar art and thought) and the hypocritical bourgeois morality and family values that had supported the nationalism culminating in World War I.2 Conversely, in Hugo Ball's words, Dada “drives toward the in- dwelling, all-connecting life nerve,” reconnecting art with the class and national conflicts informing life in the world.”3 Dada thus performed itself as radically challenging the apoliticism of European modernism as well as the debased, sentimentalized culture of the bourgeoisie through the destruction of the boundaries separating the aesthetic from life itself. But Dada has paradoxically been historicized and institutionalized as “art,” even while it has also been privileged for its attempt to explode the nineteenth-century romanticism of Charles Baudelaire's “art for art's sake.”4 Moving against the grain of most art historical accounts of Dada, which tend to focus on and fetishize the objects produced by those associated with Dada, 5 I explore here what I call the performativity of Dada: its opening up of artistic production to the vicissitudes of reception such that the process of making meaning is itself marked as a political-and, specifically, gendered-act. -

AMELIA G. JONES Robert A

Last updated 4-15-16 AMELIA G. JONES Robert A. Day Professor of Art & Design Vice Dean of Critical Studies Roski School of Art and Design University of Southern California 850 West 37th Street, Watt Hall 117B Los Angeles, CA 90089 USA m: 213-393-0545 [email protected], [email protected] EDUCATION: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES. Ph.D., Art History, June 1991. Specialty in modernism, contemporary art, film, and feminist theory; minor in critical theory. Dissertation: “The Fashion(ing) of Duchamp: Authorship, Gender, Postmodernism.” UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA, Philadelphia. M.A., Art History, 1987. Specialty in modern & contemporary art; history of photography. Thesis: “Man Ray's Photographic Nudes.” HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge. A.B., Magna Cum Laude in Art History, 1983. Honors thesis on American Impressionism. EMPLOYMENT: 2014-present UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, Roski School of Art and Design, Los Angeles. Robert A. Day Professor of Art & Design and Vice Dean of Critical Studies. 2010-2014 McGILL UNIVERSITY, Art History & Communication Studies (AHCS) Department. Professor and Grierson Chair in Visual Culture. 2010-2014 Graduate Program Director for Art History (2010-13) and for AHCS (2013ff). 2003-2010 UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER, Art History & Visual Studies. Professor and Pilkington Chair. 2004-2006 Subject Head (Department Chair). 2007-2009 Postgraduate Coordinator (Graduate Program Director). 1991-2003 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, RIVERSIDE, Department of Art History. 1999ff: Professor of Twentieth-Century Art and Theory. 1993-2003 Graduate Program Director for Art History. 1990-1991 ART CENTER COLLEGE OF DESIGN, Pasadena. Instructor and Adviser. Designed and taught two graduate seminars: Contemporary Art; Feminism and Visual Practice.