No. 4 in a Minor STENHAMMAR QUARTET

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

The Glasgow Season 2014/2015

A World of Music at Glasgow City Halls THE GLASGOW SEASON 2014/2015 BOX OFFICE: 0141-353 8000 bbc.co.uk/bbcsso #bbcssothursday ‘It has been my intention to bring some of the fi nest singers, soloists and conductors to Scotland and to showcase the brilliance, fl exibility and commitment of this remarkable group of musicians.’ THE GLASGOW SEASON 2014/2015 In September 2014 it will be fi ve years since I took up the post of Chief I’m also delighted that this year I’ll be celebrating an important birthday Conductor with this wonderful orchestra. Our relationship continues in Scotland with arguably the fi nest present a conductor could ask for to blossom, and I am immensely proud of our achievements so far. It - Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The orchestra and I will be joined by has been my intention to bring some of the fi nest singers, soloists and a world-class line-up of soloists, and our friends the Edinburgh Festival All concerts are scheduled conductors to Scotland and to showcase the brilliance, fl exibility and Chorus, for what promises to be a very memorable occasion. I hope you to be recorded for future commitment of this remarkable group of musicians. The 2014/15 season can be there. transmission or broadcast is no exception. BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra facebook.com/bbcsso live on BBC Radio 3. Our theme this season in Glasgow is ‘discovery’ so whether you’re a BBC Scotland twitter.com/bbcsso We open with Dmitri Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony and will later regular subscriber to the Thursday Night Series or an occasional visitor perform his enigmatic Fifteenth, as well as the First Piano Concerto to our wonderful home at City Halls, I’m certain you will fi nd something City Halls, Candleriggs youtube.com/bbcsso with Garrick Ohlsson; we’ll be exploring connections between the new in the evenings ahead to intrigue, delight and surprise you. -

WILHELM STENHAMMAR Excelsior! Symphony No

WILHELM STENHAMMAR Excelsior! Symphony No. 2 Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra · Neeme Järvi STENHAMMAR, Wilhelm (1871–1927) 1 Excelsior! symphonic overture, Op.13 (1896) 12'10 Symphony No.2 in G minor, Op.34 (1911–15) 42'37 2 I. Allegro energico 11'02 3 II. Andante 9'02 4 III. Scherzo. Allegro, ma non troppo presto 7'13 5 IV. Finale. Sostenuto — Allegro vivace alla breve 14'18 TT: 55'52 Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra Neeme Järvi conductor 2 he two works on this record show completely different sides of the composer Wilhelm Stenhammar. The symphonic concert overture Excelsior! written Tin 1896 is one of his very first orchestral works, composed by an un - disciplined disciple of Wagner, while the Symphony in G minor from 1915 is much more precise in its articulation, both simple in utterance and formally perfect. After training in his native city of Stockholm, Stenhammar was often in Berlin in the 1890s. He studied the piano there with Heinrich Barth in 1892–93 and was later engaged as a soloist on several occasions. With Richard Strauss conducting he played, for instance, his own Piano Concerto in B flat minor. Stenhammar nat- ur ally came into contact with a great deal of Germanic music and himself composed mu sical dramas in a Wagnerian style and piano music using a Brahmsian palette. A boisterously youthful temperament pervades Excelsior! The main theme is intro duced Leidenschaftlich bewegt (impassioned) by the strings to the accompani - ment of insistent triplets from the woodwind. The secondary theme is presented first by the clarinet and then by flute and bassoon. -

Digital Concert Hall Programme 2018/2019 3

2 DIGITAL CONCERT HALL PROGRAMME 2018/2019 3 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL The 2018/2019 season marks a very special Zubin Mehta. Another highlight is the return phase in the history of the Berliner Philhar- on two occasions of Sir Simon Rattle, and moniker. Following on from the end of the with several debuts, new artistic connections Simon Rattle era, it is characterised by look- will also be made. Among the top-class guest ing forward to a new beginning when Kirill soloists is the pianist Daniil Trifonov to name Petrenko takes up office as chief conductor. but one, the Berliner Philharmoniker’s current Although this is not due until the summer of Artist in Residence. 2019, exciting joint concerts are on the hori- zon, beginning with the season opening con- Another special feature of this season: cert which is dedicated to the core repertoire the 10th anniversary of the Digital Concert of the Berliner Philharmoniker: a Beethoven Hall. On 17 December 2008, this unprece- symphony and two symphonic poems by dented project went online, followed by a first Richard Strauss. In the Digital Concert Hall live broadcast on 6 January 2009. Since then, we are also showing a tour concert from Lu- around 50 live concerts have been shown cerne, a programme with works by Schoen- per season. The video archive now holds more berg and Tchaikovsky in the spring of 2019, than 500 concert recordings, from the and Kirill Petrenko appears at the helm of the present day back to the Karajan era. There National Youth Orchestra of Germany as well. -

1 Montag, 02.08.2021 00:00 1LIVE Fiehe Freestylesendung Mit

Montag, 02.08.2021 13:00 WDR 2 Das Leitung: Radoslaw Szulc Mittagsmagazin Johann Adolf Hasse: Darin: Violoncellokonzert D-Dur; zur vollen Stunde WDR Jan Vogler; Münchener aktuell Kammerorchester, Leitung: zur halben Stunde WDR Reinhard Goebel aktuell und Lokalzeit auf Francis Poulenc: 00:00 1LIVE Fiehe WDR 2 Concert champêtre; Maggie Freestylesendung mit Klaus 15:00 WDR 2 Sommerradio Cole, Cembalo; City of Fiehe Darin: London Sinfonia, Leitung: seit 22:00 Uhr zur vollen Stunde WDR Richard Hickox Johann Baptist Vanhal: 01:00 Die junge Nacht der ARD aktuell Sinfonie Es-Dur; Toronto Darin: zur halben Stunde bis 17:30 Chamber Orchestra, zur vollen Stunde WDR WDR aktuell und Lokalzeit Leitung: Kevin Mallon aktuell auf WDR 2 18:40 Der Stichtag ab 04:03: 05:00 1LIVE (Wiederholung von 09:40) Franz Schubert: Die tägliche, aktuelle 20:00 WDR 2 POP! Quartettsatz c-Moll, D 703; Morgen-Show in 1LIVE Darin: Signum Quartett 10:00 1LIVE zur vollen Stunde WDR Joseph Haydn: Der Vormittag in 1LIVE aktuell Sinfonie Nr. 90 C-Dur; hr- 14:00 1LIVE 23:30 WDR 2 Podcast Sinfonieorchester, Leitung: Der Nachmittag in 1LIVE Sommerfestival Hugh Wolff 18:00 1LIVE Carl Maria von Weber: Die Themen des Tages im 6 Stücke, op. 10; Duo Sektor d'Accord 20:00 1LIVE Plan B ab 05:03: Der Abend in 1LIVE - im Evaristo Felice dall'Abaco: Zeichen der Popkultur Concerto a-Moll, op. 2,4; 23:00 1LIVE Reportage Concerto Köln Der Traum von Olympia 00:00 ARD Radiofestival. Robert Schumann: Von Daniel Sondergeld Nachrichten Allegro molto vivace aus der 00:03 Das ARD Nachtkonzert Sinfonie Nr. -

Wilhelm Stenhammar

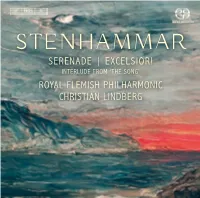

STENHAMMAR SERENADE | EXCELSIOR! INTERLUDE FROM ‘THE SONG’ ROYAL FLEMISH PHILHARMONIC CHRISTIAN LINDBERG Royal Flemish Philharmonic © Alidoor Dellafaille BIS-2058 BIS-2058_f-b.indd 1 2014-01-20 13.48 STENHAMMAR, Wilhelm (1871–1927) 1 Excelsior! symphonic overture, Op. 13 (1896) 13'50 2 Mellanspel ur Sången, Op. 44 (1921) 6'14 Interlude from The Song Molto adagio, solenne Serenade in F major, Op. 31 (1914/19) 37'16 3 I. Overtura. Allegrissimo 6'49 4 II. Canzonetta. Tempo di valse, un poco tranquillo 5'54 5 III. Scherzo. Presto 7'40 6 IV. Notturno. Andante sostenuto 7'40 7 V. Finale. Tempo moderato 9'00 TT: 58'19 Royal Flemish Philharmonic Marta Sparnina leader Christian Lindberg conductor 2 t is said that the composer Wilhelm Stenhammar (1871–1927) began every work day by asking himself ‘What is a note?’ Behind this constant return to a Isort of Cartesian origin we can discern a sharp musical intellect, capable of great things but also with a certain inclination towards crushingly severe self-cri ti - cism. The history of Stenhammar’s œuvre testifies to both of these aspects – some - times combining artistic triumph and disappointment in the same piece of music. Florez and Blanzeflor, the work of a precocious youth, caused a sensation, as did his début as soloist – aged just over twenty – in his own First Piano Concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. The concert overture Excelsior!, completed in September 1896, was first per - formed on 28th December of that year by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Arthur Nikisch, while the orchestra was on tour in Copenhagen. -

Wilhelm Stenhammar

Wilhelm Stenhammar WilhelmStenhammar(1871–1927)tillhörde storanamnen i svenskmusikhis- toria – i dag mest känd som tonsättare,under sin korta livstidlika respekterad sompianist och dirigent.Det hör till sakenatt Stenhammar var verksamnär det modernamusiklivetformades,och de främstanamnen under denna epok har aldrigförloratsin lyskraft.För Stenhammarsdel illustrerasdet avde kom- positionersomstadigt behållitsin platssomrepertoarverk,i förstahand hans förstapianokonsert(b-moll),Två sentimentalaromanserför violinoch orkester, pianoverketSensommarnätter, solosångersom”Flickankom från sin älsklings möte”samt körsångerna”Sverige”och”I serallietshave”. WilhelmStenhammarskaade sigen gedigenoch framförallt bred mu- sikaliskskolning:pianostudiervid Richard Anderssonsmusikskola,orgelför WilhelmHeintze och AugustLagergren,kontrapunkt för JosephDente, kom- positionför Emil Sjögrenoch AndreasHallén. Som så många andra svenska musikstuderandevid denna tid, och tidigare,for Stenhammarocksåutom- lands,till Berlinför pianostudier. Redan under studietidenbörjadeStenhammarframträdasom pianist, men ocksåkomponera.Sompianist inleddehan ett samarbetemed violinistenTor Aulinoch dennesstråkkvartett somskullekomma att utvecklakammarmusi- cerandei Sverige.Derasturnéer runt om i landet är legendariska. Stenhammarvar dirigentför körenFilharmoniskasällskapeti Stockholm 1897–1900.1902 var han med att grunda det som idagbenämns Kungliga Filharmonikernai Stockholm.Han dirigeradei perioderocksåvid Kungl. Teaternoch var åren 1907–22konstnärligledareför dåvarandeGöteborgs -

BIS-CD-219 Booklet Scan.Pdf-922500.Pdf

How shouid one reacl to thc idea of perfornring Stonhanrntar's [j ntajor sl.rnphorlv an(l tl]en rssurrg a recorciing of it? Ihe conrposer hinrsc,lf chosl to \!itlr(lraw tltc rvork for revision althou{ll tlt('first perlormance had ltecn well receivctl l here arr, ( \(,n suggcsli"n\ tlrrt h, r,'jIr t, rl tlr, ri rir1,l(rrrr lt has hou'cver ltcen tltampioncrl bl such inlcnlati()Dallv acclaimcd con(lucl()rsas Vaclav laliclt. Scrgirr (ionrissiona and Nocmc Jrirvi, who ltavt enLhusiastrcalll prcparecl sortlo of tlrf rare lrrrblic prrforrriart cs oltha'w()rk.1'lleb(,auticsofthes\n1l)llon\arfalsoonrl)hasizo(lil\or(.ltcstralrnusi<,iansu,hilslautli enceshavebeent-aptivatt'tl. i\rtcorclingslroulrllhlreforeltcjustifie<1.bothLoallorvasnlan\iisposs rble to cnj()l th. {'ork an(l t() givc llre nrusic a (on(rft('ol)portunil} t() conlbun(l tirc scr'ptics- }1an1 well known sorks in nrusical historl havc a cleceptivc lustre thcir glitt.r l)roduccs varii'(l roactions in clilfer<'nt iistencrs. In tho Srvldish s1nrphonic rel)fr1()jr( Stt'nhanrrnar's monullrenlal l.' r)rajor symplronyshineswilhparticuiarsplrDdour. \\r'r,anitlaflorcltolt,av0thisworkunplav(,(1. (lomposer, pianist ancl conductor, IVILHIILNI STEi\HAllitAR harl b1 thc br:ginning ()f ll)e cfDtrrr\' bcconlt. one of Scandinavia s leading Iriusical figures. Ilis tlebul iit a larger iontcxt took pracr rn Stt>ckholttt in 1E92, $'here hc featurecl as conrl)os('r and pialo sol()ist in !arious (onccrts. i.'i,rsr,,r, \'earsoncsuccessfollolvcdatlother.'llre ltNtpiatt()t()tltt,rl() wr.\l)('r1()rntc(laltroarl,uiLhstcnlratrtntar itinself as soloist, bl the Bcrlin C)pera OrchcsLra Lurrli'r Ilichiirtl Strauss and br the IlalleiOrcncslra ln flallcllesl€rr undcr llans Richler. -

WILH ELM STENH AMM AR Sverige Sweden

WILHELM STENHAMMAR 1871 1927 Sverige för röst och piano Sweden for voice and piano Opus 22 nr 2 / Opus 22 no. 2 mellan/ middle Emenderad utgåva/Emended edition LevandeMusikarv och Kungl. Musikaliska akademien Syftetmed LevandeMusikarv är att tillgängliggöraden dolda svenska musikskattenoch göraden till en självklardel av dagensrepertoar och forskning.Detta skergenomnotutgåvorav musik som inte längreär skyd- dad av upphovsrätten,samt texter om tonsättarna och deras verk.Texterna publicerasi projektetsdatabaspå internet, liksom fritt nedladdningsbara notutgåvor.Huvudman är Kungl. Musikaliskaakademieni samarbetemed Musik-och teaterbiblioteketoch SvenskMusik. Kungl. Musikaliskaakademiengrundades 1771 av GustavIII med än- damålet att främja tonkonsten och musikliveti Sverige.Numera är akade- mien en friståendeinstitution som förenartradition med ett aktivt engage- mang i dagensoch morgondagensmusikliv. SwedishMusical Heritage and e Royal SwedishAcademyof Music e purposeof SwedishMusicalHeritageis to make accessibleforgotten gemsof Swedishmusicand make them a natural featureof the contemporary repertoireand musicology.is it doesthrough editionsof sheetmusicthat is no longerprotectedby copyright,and textsabout the composersand their works.is materialis availablein the project’sonlinedatabase,wherethe sheetmusiccan be freelydownloaded.e projectis run under the auspices of the RoyalSwedishAcademyofMusicin associationwiththe Musicand eatre Libraryof Swedenand SvenskMusik. e RoyalSwedishAcademyofMusicwasfoundedin 1771by King GustavIII in orderto -

Konstverk I Göteborgs Konserthus

KONSTVERK I GÖTEBORGS KONSERTHUS CELLISTEN GUIDO VECCHI Olja på duk, 100 x 96,5 cm. (Tillhör Göte borgs Stad Kultur, KN 2733). Guido Vecchi (1910-1997) var under 40 år (1936-1976) konsertmästare i cellostämman i Göteborgs symfoniorkester. Hans tolkningar av nyare, svensk musik har särskilt uppmärksammats. 1989 utnämndes han till hedersdoktor vid Konstnärliga fakulteten av Göteborgs uni versitet. Lillemor Tell Född 1920 i Stockholm. Studier vid Konstfack, Stockholm, Academie des Beaux Arts , Paris. Ett flertal samlings- och separatutställningar. 1951 gav L.T ut boken ”Mitt kvarter i Paris” som innehöll teckningar från Paris. Representerad på Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Göteborgs konstmuseum, Statens Konstråd, Norrköpings museum, m.fl. © Lillemor Tell /BUS 2009. ERIK L. MAGNUS Relief, medaljong i brons, 41,5 cm Ø. Före ställer Erik L. Magnus som var Orkesterför eningens ordförande 1935-1949. Gösta Carell (1888-1962) Född i Stockholm. Skulptör och medaljkonst när. Utbildad vid Copper Union, School of Beaux Arts, USA. Representerad på Na tionalmuseum, Stockholm, Waldemarsudde, Stockholm, Göteborgs konstmuseum, Statens Museum for Kunst, Köpenhamn, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, m.fl. ISSAY DOBROWEN Porträtt i brons, 34 x 21 x 16 cm (hxdxb), 1930. Ryssen Issay Dobrowen var dirigent och pianist och verkade som chefdirigent för Göteborgs Symfoniker under åren 1941 1953. Øivind Scotte Hansen Konstnär STRAVINSKIJ Porträtt i brons, 30 x 17 x 23 cm (hxdxb). Ett stiliserat porträtt av tonsättaren, pianisten och dirigenten Igor Stravinskij (1882-1971). Tillhör Göteborgs Stad Kultur, KN 2008. Börge Hovedskou (1910-1966) Konstnär och grundare av Hovedskous målarskola i Göteborg. Utbildad vid Kunsta kademien i Köpenhamn 1930-1935. NEEME JÄRVI Porträtt i brons, 40 x 21 x 28 cm (hxdxb). -

Mitt Instrument: Erik Risberg

Mitt instrument: Erik Risberg E.S.T. SYMPHONY – INTERVJU MED HANS EK MELISSA ALDANA BLÅSER NYTT LIV I JAZZEN FINLAND OCH GÖTEBORGS SYMFONISKA KÖR 100 ÅR! TRE DAGAR MED MESSIAS Kära musik- ANSVARIG UTGIVARE Urban Ward vänner! NYA VOLVO V90 REDAKTÖR Stefan Nävermyr FORMGIVNING Magdalena Nilsson Gustav Mahler är för många musik- CROSS COUNTRY älskare den störste symfonikern av dem SKRIBENTER Ulla M Andersson, Sture Carlsson, Sten alla. Han representerar allt vad en Cranner, Rolf Haglund, Ingemar von Heijne, symfoniorkester står för och lyckades Stig Jacobsson, Ulf Johansson, Katarina A förädla orkestern som kollektivt instrument Karlsson, Stefan Nävermyr, Johan Scherwin, Per Stern, Gunilla Petersén, Lotta Wennäkoski till fulländning. Alla orkestrar tar sig an en och Magnus Öström Mahler-symfoni med största respekt – det är med FOTO stor vördnad hans verk programmeras i ett säsongsprogram Anna-Lena Ahlström Kungahuset Ahmadeloufi, och man ger inte uppdraget till vilken dirigent som helst. Tina Axelsson, baxxer, Giorgia Bertazzi, Marco Denna säsong har vi lyckas programmera tre av Mahlers nio Borggreve, Brissaud, Måns Pär Fogelberg, fullbordade symfonier. I september dirigerade Susanna Mälkki Simon Fowler, Stina Gullander, Getty Images, Dan Holmqvist, Lisbeth Holten, Anna Hult, Jonas den fjärde symfonin och i maj kan ni uppleva Kent Nagano och Jörneberg, Kaapu Kamu, Jarmo Katila, Ola Kjel- Symfonikerna göra den sällan framförda tredje symfonin. Men bye, Emelie Kroon, Maarit Kytöharju, Francis närmast, i månadsskiftet november-december kommer världsdiri- Löfvenholm, Karl Melander, Erik Mofjell, Outi Montosen, Stefan Nävermyr, Luca Piva, Nadja genten Christoph Eschenbach på ett efterlängtat återbesök för att Pollack, Dragan Popovic, Klaus Rudolph, Wendy göra Mahlers Symfoni nr 6, ”Den tragiska”. -

2020-2021 Season Chronology of Events

Carnegie Hall 2020–2021 Season Chronological Listing of Events All performances take place at Carnegie Hall, 57th Street and Seventh Avenue, unless otherwise indicated. October CARNEGIE HALL'S Wednesday, October 7, 2020 at 7:00 PM OPENING NIGHT GALA Los Angeles Philharmonic LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Gustavo Dudamel, Music and Artistic Director Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage Lang Lang, Piano Liv Redpath, Soprano JOHN ADAMS Tromba Lontana EDVARD GRIEG Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 16 EDVARD GRIEG Selections from Peer Gynt DECODA Thursday, October 8, 2020 at 7:30 PM Weill Recital Hall Decoda LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 FRANZ SCHUBERT String Trio in B-flat Major, D. 471 GUSTAV MAHLER Selection from "Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell" from Symphony No. 1 in D Major (arr. Decoda) ARNOLD SCHOENBERG Selections from Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 (arr. Decoda) VARIOUS COMPOSERS Ode to Beethoven (World Premiere created in collaboration with the audience) LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Thursday, October 8, 2020 at 8:00 PM Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage Los Angeles Philharmonic Gustavo Dudamel, Music and Artistic Director Leila Josefowicz, Violin Gustavo Castillo, Narrator GABRIELLA SMITH Tumblebird Contrails (NY Premiere) ANDREW NORMAN Violin Concerto (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) ALBERTO GINASTERA Estancia, Op. 8 Andrew Norman is holder of the 2020-2021 Richard and Barbara Debs Composer's Chair at Carnegie Hall. LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Friday, October 9, 2020 at 8:00 PM Stern Auditorium / Perelman