Care Coordination for California's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0281166 A1 BHATTACHARJEE Et Al

US 20160281 166A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0281166 A1 BHATTACHARJEE et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 29, 2016 (54) METHODS AND SYSTEMIS FOR SCREENING Publication Classification DISEASES IN SUBJECTS (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: PARABASE GENOMICS, INC., CI2O I/68 (2006.01) Boston, MA (US) C40B 30/02 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Arindam BHATTACHARJEE, G06F 9/22 (2006.01) Andover, MA (US); Tanya (52) U.S. Cl. SOKOLSKY, Cambridge, MA (US); CPC ............. CI2O 1/6883 (2013.01); G06F 19/22 Edwin NAYLOR, Mt. Pleasant, SC (2013.01); C40B 30/02 (2013.01); C12O (US); Richard B. PARAD, Newton, 2600/156 (2013.01); C12O 2600/158 MA (US); Evan MAUCELI, (2013.01) Roslindale, MA (US) (21) Appl. No.: 15/078,579 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Mar. 23, 2016 Related U.S. Application Data The present disclosure provides systems, devices, and meth (60) Provisional application No. 62/136,836, filed on Mar. ods for a fast-turnaround, minimally invasive, and/or cost 23, 2015, provisional application No. 62/137,745, effective assay for Screening diseases, such as genetic dis filed on Mar. 24, 2015. orders and/or pathogens, in Subjects. Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 1 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS S{}}\\93? sau36 Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 2 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 &**** ? ???zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz??º & %&&zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz &Sssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss & s s sS ------------------------------ Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 3 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 23 25 20 FG, 2. Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 4 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 : S Patent Application Publication Sep. -

Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. I. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagets)". II' it was possible to obtain the missing pagers) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cu tting th rough an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark. it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, J good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, ctc., is part of the material being photographed. a definite method of "sectioning" the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Attachment a Rare and Expensive Disease List As of December 27, 2010 ICD-9 Age Disease Guidelines Code Group 042

Attachment A Rare and Expensive Disease List as of December 27, 2010 ICD-9 Age Disease Guidelines Code Group 042. Symptomatic HIV disease/AIDS 0-20 (A) A child <18 mos. who is known to be HIV (pediatric) seropositive or born to an HIV-infected mother and: * Has positive results on two separate specimens (excluding cord blood) from any of the following HIV detection tests: --HIV culture (2 separate cultures) --HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) --HIV antigen (p24) N.B. Repeated testing in first 6 mos. of life; optimal timing is age 1 month and age 4-6 mos. or * Meets criteria for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) diagnosis based on the 1987 AIDS surveillance case definition V08 Asymptomatic HIV status 0-20 (B) A child >18 mos. born to an HIV-infected (pediatric) mother or any child infected by blood, blood products, or other known modes of transmission (e.g., sexual contact) who: * Is HIV-antibody positive by confirmatory Western blot or immunofluorescense assay (IFA) or * Meets any of the criteria in (A) above 795.71 Infant with inconclusive HIV result 0-12 (E) A child who does not meet the criteria above months who: * Is HIV seropositive by ELISA and confirmatory Western blot or IFA and is 18 mos. or less in age at the time of the test or * Has unknown antibody status, but was born to a mother known to be infected with HIV 270.0 Disturbances of amino-acid 0-20 Clinical history and physical exam; laboratory transport studies supporting diagnosis. Subspecialist Cystinosis consultation note may be required. -

Diseases Catalogue

Diseases catalogue AA Disorders of amino acid metabolism OMIM Group of disorders affecting genes that codify proteins involved in the catabolism of amino acids or in the functional maintenance of the different coenzymes. AA Alkaptonuria: homogentisate dioxygenase deficiency 203500 AA Phenylketonuria: phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) 261600 AA Defects of tetrahydrobiopterine (BH 4) metabolism: AA 6-Piruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency (PTS) 261640 AA Dihydropteridine reductase deficiency (DHPR) 261630 AA Pterin-carbinolamine dehydratase 126090 AA GTP cyclohydrolase I deficiency (GCH1) (autosomal recessive) 233910 AA GTP cyclohydrolase I deficiency (GCH1) (autosomal dominant): Segawa syndrome 600225 AA Sepiapterin reductase deficiency (SPR) 182125 AA Defects of sulfur amino acid metabolism: AA N(5,10)-methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency (MTHFR) 236250 AA Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency (CBS) 236200 AA Methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency 250850 AA Methionine synthase deficiency (MTR, cblG) 250940 AA Methionine synthase reductase deficiency; (MTRR, CblE) 236270 AA Sulfite oxidase deficiency 272300 AA Molybdenum cofactor deficiency: combined deficiency of sulfite oxidase and xanthine oxidase 252150 AA S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency 180960 AA Cystathioninuria 219500 AA Hyperhomocysteinemia 603174 AA Defects of gamma-glutathione cycle: glutathione synthetase deficiency (5-oxo-prolinuria) 266130 AA Defects of histidine metabolism: Histidinemia 235800 AA Defects of lysine and -

BOOK REVIEWS 567 Prenatal Diagnosis and Selective Abortion

BOOK REVIEWS 567 Prenatal Diagnosis and Selective Abortion. By H. HARRIS. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, 1974. Pp. 101. 11.75. U.S. publisher, Harvard University Press. The recent introduction of prenatal detection of genetic disorders has raised a variety of ethical and biological questions. This book not only reviews a number of problems with intrauterine diagnosis, including the scope of the procedure and its effects on the incidence of genetic diseases, but it also raises a number of ethical questions which have generated considerable discussion in both professional and nonprofessional fields. The text is authored by an acknowledged expert in the field of human genetics. Harris has divided his thesis into three major chapters. The first presents an overview of the present state of knowledge of intrauterine diagnosis as it relates to chromosomal abnor- malities, X-linked disorders, metabolic diseases, and congenital malformations. This section does not contain an extensive review of the literature but does highlight many of the more important aspects. The second section deals with effects on the incidence of genetic disease. It outlines both the potential short- and long-term effects that are expected to follow from selective abortion whether the abnormality is a single gene or classical Mendelian condition, a gross chromosomal defect, or a disorder regarded as multifactorial in origin. The last section, which is the most interesting in my opinion, deals with the question of ethics. Harris not only clearly points out the ethical and moral questions of selective abortion, including the undesirable aspects, but he also describes the visible benefits which, in his opinion, make intrauterine detection a valuable advance in medicine. -

Diagnose a Broad Range of Metabolic Disorders with a Single Test, Global

PEDIATRIC Assessing or diagnosing a metabolic disorder commonly requires several tests. Global Metabolomic Assisted Pathway Screen, commonly known as Global MAPS, is a unifying test GLOBAL MAPS™ for analyzing hundreds of metabolites to identify changes Global Metabolomic or irregularities in biochemical pathways. Let Global MAPS Assisted Pathway Screen guide you to an answer. Diagnose a broad range of metabolic disorders with a single test, Global MAPS Global MAPS is a large scale, semi-quantitative metabolomic profiling screen that analyzes disruptions in both individual analytes and pathways related to biochemical abnormalities. Using state-of-the-art technologies, Global Metabolomic Assisted Pathway Screen (Global MAPS) provides small molecule metabolic profiling to identify >700 metabolites in human plasma, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid. Global MAPS identifies inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) that would ordinarily require many different tests. This test defines biochemical pathway errors not currently detected by routine clinical or genetic testing. IEMs are inherited metabolic disorders that prevent the body from converting one chemical compound to another or from transporting a compound in or out of a cell. NORMAL PROCESS METABOLIC ERROR These processes are necessary for essentially all bodily functions. Most IEMs are caused by defects in the enzymes that help process nutrients, which result in an accumulation of toxic substances or a deficiency of substances needed for normal body function. Making a swift, accurate diagnosis -

SUPPORT GUIDE Contents ORGANIC ACIDS OXIDATIVE STRESS MARKERS AMINO ACIDS FATTY ACIDS TOXIC and NUTRIENT ELEMENTS

& SUPPORT GUIDE Contents ORGANIC ACIDS OXIDATIVE STRESS MARKERS AMINO ACIDS FATTY ACIDS TOXIC AND NUTRIENT ELEMENTS Organic Acids NUTRITIONAL Oxidative Stress NUTRITIONAL Amino Acids Plasma NUTRITIONAL Essential & Metabolic Fatty Acids NUTRITIONAL Elements NUTRITIONAL 2. NutrEval Profile The NutrEval profile is the most comprehensive functional and nutritional assessment available. It is designed to help practitioners identify root causes of dysfunction and treat clinical imbalances that are inhibiting optimal health. This advanced diagnostic tool provides a systems-based approach for clinicians to help their patients overcome chronic conditions and live a healthier life. The NutrEval assesses a broad array of macronutrients and micronutrients, as well as markers that give insight into digestive function, toxic exposure, mitochondrial function, and oxidative stress. It accomplishes this by evaluating organic acids, amino acids, fatty acids, oxidative stress markers, and nutrient & toxic elements. Subpanels of the NutrEval are also available as stand-alone options for a more focused assessment. The NutrEval offers a user-friendly report with clinically actionable results including: • Nutrient recommendations for key vitamins, minerals, amino acids, fatty acids, and digestive support based on a functional evaluation of important biomarkers • Functional pillars with a built-in scoring system to guide therapy around needs for methylation support, toxic exposures, mitochondrial dysfunction, fatty acid imbalances, and oxidative stress • Interpretation-At-A-Glance pages providing educational information on nutrient function, causes and complications of deficiencies, and dietary sources • Dynamic biochemical pathway charts to provide a clear understanding of how specific biomarkers play a role in biochemistry There are various methods of assessing nutrient status, including intracellular, extracellular, direct, and functional measurements. -

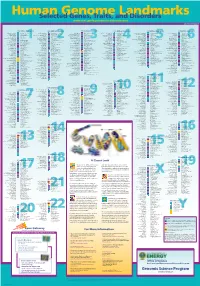

Genomeposter2009.Pdf

Fold HumanSelected Genome Genes, Traits, and Landmarks Disorders www.ornl.gov/hgmis/posters/chromosome genomics.energy. -

Serum Carnosinase Deficiency Concomitant with Mental Retardation

Pediat. Res. 7:601-606 (1973) Anserine mental retardation carnosine 1 -methylhistidine carnosinase Serum Carnosinase Deficiency Concomitant with Mental Retardation WILLIAM H. MURPHEY"81, DONALD G. LINDMARK, LINDA I. PATCHEN, MARY E. HOUSLER, EMMA K. HARROD, AND Luis MOSOVICH Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, The State University of New York at Buffalo and the Children's Hospital of Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, USA Extract A family was studied in which two boys with progressive neurologic disease exhibited carnosinemia (20-30 jumol/ml serum), carnosinuria (60-200 /xmol/24 hr), and a defi- ciency in serum carnosinase activity ( <0.03 jumol/hr/ml). Their sister, who is appar- ently both physically and mentally normal, also exhibits carnosinuria and is deficient in serum carnosinase activity. Tissue extracts of liver, kidney, and spleen obtained at autopsy of one of the male patients were assayed for carnosinase and other enzyme activities and were subjected to starch block electrophoresis at pH 7.0 for 4 hr at 4°. The starch block electro- phoreses, under conditions which readily demonstrate two electrophoretic forms of the enzyme in normal tissue extracts, revealed that only one of the two forms was present. This activity corresponded to the slower form in normal tissues and appeared to be present in normal concentrations. Speculation The excretion of abnormal quantities of carnosine and/or anserine in the urine ap- pears to be related to inherited serum carnosinase deficiency, but further studies are re- quired to determine the association of the deficiency of the enzyme with progressive neurologic disease as well as the nature and role of the two electrophoretic forms of tissue carnosinase activity. -

Prevalence of Rare Diseases: Bibliographic Data

Prevalence distribution of rare diseases 200 180 160 140 120 100 80 Number of diseases 60 November 2009 40 May 2014 Number 1 20 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 Estimated prevalence (/100000) Prevalence of rare diseases: Bibliographic data Listed in alphabetical order of disease or group of diseases www.orpha.net Methodology A systematic survey of the literature is being Updated Data performed in order to provide an estimate of the New information from available data sources: EMA, prevalence of rare diseases in Europe. An updated new scientific publications, grey literature, expert report will be published regularly and will replace opinion. the previous version. This update contains new epidemiological data and modifications to existing data for which new information has been made Limitation of the study available. The exact prevalence rate of each rare disease is difficult to assess from the available data sources. Search strategy There is a low level of consistency between studies, a poor documentation of methods used, confusion The search strategy is carried out using several data between incidence and prevalence, and/or confusion sources: between incidence at birth and life-long incidence. - Websites: Orphanet, e-medicine, GeneClinics, EMA The validity of the published studies is taken for and OMIM ; granted and not assessed. It is likely that there - Registries, RARECARE is an overestimation for most diseases as the few - Medline is consulted using the search algorithm: published prevalence surveys are usually done in «Disease names» AND Epidemiology[MeSH:NoExp] regions of higher prevalence and are usually based OR Incidence[Title/abstract] OR Prevalence[Title/ on hospital data. -

ORPHA Number Disease Or Group of Diseases 300305 11P15.4

Supplementary material J Med Genet ORPHA Disease or Group of diseases Number 300305 11p15.4 microduplication syndrome 444002 11q22.2q22.3 microdeletion syndrome 313884 12p12.1 microdeletion syndrome 94063 12q14 microdeletion syndrome 412035 13q12.3 microdeletion syndrome 261120 14q11.2 microdeletion syndrome 261229 14q11.2 microduplication syndrome 261144 14q12 microdeletion syndrome 264200 14q22q23 microdeletion syndrome 401935 14q24.1q24.3 microdeletion syndrome 314585 15q overgrowth syndrome 261183 15q11.2 microdeletion syndrome 238446 15q11q13 microduplication syndrome 199318 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome 261190 15q14 microdeletion syndrome 94065 15q24 microdeletion syndrome 261211 16p11.2p12.2 microdeletion syndrome 261236 16p13.11 microdeletion syndrome 261243 16p13.11 microduplication syndrome 352629 16q24.1 microdeletion syndrome 261250 16q24.3 microdeletion syndrome 217385 17p13.3 microduplication syndrome 97685 17q11 microdeletion syndrome 139474 17q11.2 microduplication syndrome 261272 17q12 microduplication syndrome 363958 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome 261279 17q23.1q23.2 microdeletion syndrome 254346 19p13.12 microdeletion syndrome 357001 19p13.13 microdeletion syndrome 447980 19p13.3 microduplication syndrome 217346 19q13.11 microdeletion syndrome 293948 1p21.3 microdeletion syndrome 401986 1p31p32 microdeletion syndrome 456298 1p35.2 microdeletion syndrome 250994 1q21.1 microduplication syndrome 238769 1q44 microdeletion syndrome 261295 20p12.3 microdeletion syndrome 313781 20p13 microdeletion syndrome 444051 20q11.2 -

Orphanet Report Series 180 160 Collection 140 Rare Diseases

Prevalence distribution of rare diseases 200 Orphanet Report Series 180 160 collection 140 Rare Diseases 120 100 80 Number of diseases 60 May 2009 40 November 2011 Number 2 20 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 Estimated prevalence (/100000) Prevalence of rare diseases: Bibliographic data Listed in order of decreasing prevalence or number of published cases www.orpha.net 20102206 Methodology A systematic survey of the literature is being Updated Data performed in order to provide an estimate of the New information from available data sources: EMA, prevalence of rare diseases in Europe. An updated new scientific publications, grey literature, expert report will be published regularly and will replace opinion. the previous version. This update contains new epidemiological data and modifications to existing data for which new information has been made Limitation of the study available. The exact prevalence rate of each rare disease is difficult to assess from the available data sources. Search strategy There is a low level of consistency between studies, a poor documentation of methods used, confusion The search strategy is carried out using several data between incidence and prevalence, and/or confusion sources: between incidence at birth and life-long incidence. - Websites: Orphanet, e-medicine, GeneClinics, EMA The validity of the published studies is taken for and OMIM ; granted and not assessed. It is likely that there - Medline is consulted using the search algorithm: is an overestimation for most diseases as the few «Disease names» AND Epidemiology[MeSH:NoExp] published prevalence surveys are usually done in OR Incidence[Title/abstract] OR Prevalence[Title/ regions of higher prevalence and are usually based abstract] OR Epidemiology[Title/abstract] ; on hospital data.