Issue No. 17 : Fall/Winter 2005 : Metropolitan Mosaic Theme PDF Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southside Trail Design July 12, 2016

// Southwest + Southeast Study Group: Southside Trail Design July 12, 2016 7/12/2016 Page 1 // Trails: Southside Corridor • Includes 4-mile trail between University Ave & Glenwood Ave • Design to include lighting, retaining walls, vertical connections, storm drainage, signage/wayfinding, and bridges • Federally Funded Project, following GDOT Design Process • Design to be complete in 18-24 months followed by construction 7/12/2016 Page 2 MECHANICSVILLE LEGEND EDY PUBLIC LIBRARY I - 20 NODE OPTIONS ENN FULTON WAY GLENWOOD AVE SE WAY DUNBAR GLENWOOD ELEMENTARY PARK L K VERTICAL CONNECTION SCHOOL BILL KENNEDY BILL KENNEDY BIL ROSA L BURNEY SOUTHSIDE TRAIL AT GRADE PARK HERITAGE PARK MAYNARDD CONNECTION TO ATLANTA JACKSON BELTLINE COORIDOR H.S. PHOENIX III PARK|SCHOOL|LIBRARY| PARK WINDSOR GREENSPACE STREET GRANT PARK MERCER ST SE KILLIANKKILLIKILLKIL IANAN TO FOCUS AREA PHOENIX II PARK PARKSIDEARKSIDE ELEMENELEMENTARYTA ORMEWORMEORMEWOODRMEWWOODODOD PARK SCHOOL BROWN ORMEWOODWOOD AVEE MIDDLE WELCH ORMEWOODOORORMEWOOMEWOOD SCHOOL STREET PARK PARKPARK ROSE CIRCLE ADAIR DELMAR AVE SESE DELMARDELMDEDELLMAMAR PARK PARK II ORMOND AVEAVENUEENUENUNUE CHARLES L GRANT GIDEONS PARK ELEMENTARY VARD SE SCHOOL GGRANTRANT PPARKARK PPEOPLESEOPLES TTOWNOWN SE AVE CHEROKEE BOULEVARD SE BOULEVARD PITMAN SE BOULEVARD LEE ST AADAIRDAIR D.H. STANTON PARK E CCONFEDERATECONFEDE AVE SE I - 75 ELEMENTARY O PPARKARK PPITTSBURGHITTSBURGH SCHOOL RAATE AVE SE OOAKLANDAKLAND FOUR D.H. STANTON CORNERS WALTER LEONARD PARK PARK HILL ST SE CCITYITY ADAIR PARKS MIDDLE PARK I JACCIJAC FULLER ALLENE AVE SW ALLENE AVE SCHOOL WOODLAND GARDEN BBOULEVARDOULEVARD PARK METROPOLITAN PKWY METROPOLITAN BOULEVARD HANK AARON DR SE HANK AARON CCHOSEWOODHOSEWOOD HHEIGHTSEIGHTS CARVER D.H. CROSSING SCHOOLS FINCH UNIVERSITY AVE MILTONSTANTON AVE SE PPARKARK PARK ELEMENTARY TO PARK SCHOOL MCDONOUGH BLVDO SE EENGLEWOODNGLEWOOD THE REV. -

Haven at South Atlanta

A MARKET CONDITIONS AND PROJECT EVALUATION SUMMARY OF: HAVEN AT SOUTH ATLANTA A MARKET CONDITIONS AND PROJECT EVALUATION SUMMARY OF: HAVEN AT SOUTH ATLANTA 57 Hardwick Street SE Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia 30315 Effective Date: April 17, 2019 Report Date: April 19, 2019 Prepared for: Amon Martin Senior Developer Pennrose, LLC 675 Ponce de Leon Avenue NE, Suite 8500 Atlanta, Georgia 30308 Prepared by: Novogradac & Company LLP 4416 East-West Highway, Suite 200 Bethesda, MD 20814 240-235-1701 April 19, 2019 Amon Martin Senior Developer Pennrose, LLC 675 Ponce de Leon Avenue NE, Suite 8500 Atlanta, Georgia 30308 Re: Application Market Study for Haven at South Atlanta, located in Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia Dear Mr. Martin: At your request, Novogradac & Company LLP performed a study of the multifamily rental market in the Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia area relative to the above-referenced Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) project. The purpose of this market study is to assess the viability of the proposed 84-unit family mixed-income project. It will be a newly constructed affordable LIHTC project, with 84 revenue generating units, restricted to households earning and 60 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI) or less as well as market rate. The following report provides support for the findings of the study and outlines the sources of information and the methodologies used to arrive at these conclusions. The scope of this report meets the requirements of Georgia Department of Community Affairs (DCA), including the following: • Inspecting the site of the proposed Subject and the general location. • Analyzing appropriateness of the proposed unit mix, rent levels, available amenities and site. -

Atlanta Beltline Subarea 3 Master Plan Update August 26, 2019 Study Group

Atlanta BeltLine Subarea 3 Master Plan Update August 26, 2019 Study Group Boulevard Crossing Park 1 September 22 miles, connecting 45 neighborhoods 22 1,100 ACRES MILES of environmental of transit clean-up $10B 46 in economic development MILES of streetscapes and complete 30,000 48,000 streets permanent jobs construction jobs 28,000 33 new housing units MILES of urban trails 5,600 affordable units 1,300 CORRIDOR- ACRES of new greenspace WIDE public art, 700 historic preservation, ACRES of renovated greenspace and arboretum Atlanta BeltLine Vision & Mission To be the catalyst for making We are delivering transformative public infrastructure Atlanta a global beacon for that enhances mobility, fosters culture, and improves equitable, inclusive, and connections to opportunity. We are building a more sustainable city life. socially and economically resilient Atlanta with our partner organizations and host communities through job creation, inclusive transportation systems, affordable housing, and public spaces for all. 3 Subarea Master Plan Purpose • Goal - To implement the Redevelopment Plan goals in the context of each unique geographic area • Purpose – To guide growth for vibrant, livable mixed-use communities by applying best management practices for transit oriented development, mobility, green space, and alternative modes of transportation. Subarea Master Plan Update Purpose • The original 10 Subarea Master Plans created ~10 years ago • A lot has happened – it’s time to update them to reflect these changes and the potential for the future -

Atlanta Has Seen a Rapid Increase in Population Over the Course of Only a Few Years, and the City’S Newfound Popularity Comes As No Surprise

Atlanta has seen a rapid increase in population over the course of only a few years, and the city’s newfound popularity comes as no surprise. Currently, there are 5.7 million people in the metro Atlanta area with numbers projected to continue to rise. Atlanta boasts a prosperous job market, a diverse community, a lively weekend scene, gourmet food options and a landscape that combines busy metropolitan vibes with the calming green spaces of the countryside. Whether you’re strolling through Atlanta’s beautiful Botanical Gardens or biking along the Atlanta Beltline, you will never run out of things to do. People from around the country – and world – are discovering the appeal of Atlanta, and it has quickly become a well-respected center of commerce and creativity. To illustrate Atlanta’s wide range of communities, we interviewed Kabbage employees so they can share what it’s like to live in each of their unique neighborhoods. The Westside, known amongst the Atlanta community as a trendy and fun area, is quickly growing in popularity. The area stretches from the west end of Georgia Tech to southwest Buckhead. Recently, this area has undergone renovation with new apartment and condo buildings sprouting up. Jeff, one of Kabbage’s Recruiters, is a Westside resident who described the Westside as a place that has quickly transformed from an industrial area into an eclectic and diverse place that presents a fun mix of neighborhoods, commercial and retail. The area is varied in many realms; it attracts both college students and families, you can choose to eat fast food or indulge in fine dining, and, if you are in the mood to spend some money, you can visit local shops, or alternatively do some chain retail shopping. -

Atlanta Beltline Redevelopment Plan

Atlanta BeltLine Redevelopment Plan PREPARED FOR The Atlanta Development Authority NOVEMBER 2005 EDAW Urban Collage Grice & Associates Huntley Partners Troutman Sanders LLP Gravel, Inc. Watercolors: Rebekah Adkins, Savannah College of Art and Design Acknowledgements The Honorable Mayor City of Atlanta The BeltLine Partnership Shirley C. Franklin, City of Atlanta Fulton County The BeltLine Tax Allocation District Lisa Borders, President, Feasibility Study Steering Commi�ee Atlanta City Council Atlanta Public Schools The Trust for Public Land Atlanta City Council Members: Atlanta Planning Advisory Board (APAB) The PATH Foundation Carla Smith (District 1) Neighborhood Planning Units (NPU) Friends of the BeltLine Debi Starnes (District 2) MARTA Ivory Young Jr. (District 3) Atlanta Regional Commission Cleta Winslow (District 4) BeltLine Transit Panel Natalyn Archibong (District 5) Anne Fauver (District 6) Howard Shook (District 7) Clair Muller (District 8) Felicia Moore (District 9) C. T. Martin (District 10) Jim Maddox (District 11) Joyce Sheperd (District 12) Ceasar Mitchell (Post 1) Mary Norwood (Post 2) H. Lamar Willis (Post 3) Contents 1.0 Summary 1 7.0 Types of Costs Covered by TAD Funding 2.0 Introduction 5 and Estimated TAD Bond Issuances 77 2.1 The BeltLine Concept 5 7.0.1 Workforce Housing 78 2.2 Growth and Development Context 5 7.0.2 Land Acquisition–Right-of-Way, 2.3 Historic Development 7 Greenspace 78 2.4 Feasibility Study Findings 8 7.0.3 Greenway Design and Construction 78 2.5 Cooperating Partners 9 7.0.4 Park Design and Construction -

Schedule of Events

Schedule of Events Wednesday, February 28 Thursday, March 1 12:00 Noon–7:00 PM 8:00 AM–5:00 PM W100. Conference Registration. R100. Conference Registration. T h u r s d a y , Lobby Level Lobby Level Attendees who have registered in advance may pick up their reg- Attendees who have registered in advance may pick up their reg- istration materials throughout the day at AWP’s registration desk. istration materials throughout the day at AWP’s registration desk. On-site registration passes are available for purchase. On-site registration passes are available for purchase. 12:00 Noon–5:30 PM 8:30 AM–5:30 PM W101. Bookfair Setup. R101. Bookfair. Exhibit Hall, Lower Level Exhibit Hall, Lower Level The exhibit hall on the lower level of the Hilton Atlanta will be open for exhibitor setup. Only those wearing an exhibitor badge, 9:00–10:15 AM M a r c h 1 , or those accompanied by an individual wearing an exhibitor badge will be permitted inside the exhibit hall during setup hours. Book- R102. Evolution of a Writer: On Ekeing, Emerging, and Be- fair exhibitors are welcome to pick up their registration materials coming Established. in the registration area located on the lobby level of the Hilton (Matt Roberts, Steven Church, Adam Braver) Atlanta. Salon B, 2nd Floor How does one move from trying to eke out a place for themselves 5:00–6:30 PM in the pages of literary journals to the New York Times Bestseller List? This panel will address the professional development of writ- W102. -

2014 Urban Tree Canopy Study Here

Assessing Urban Tree Cover in the City of Atlanta: Phase 2 (Detecting Canopy Change 2008-2014) Prepared by: Center for Spatial Planning Analytics and Visualization (formerly known as the Center for Geographic Information Systems or CGIS) 760 Spring St Atlanta, GA 30332-0695 Office: 404-894-0127 Georgia Institute of Technology Investigators: Anthony Giarrusso, Associate Director (CSPAV), [email protected] Sponsor: City of Atlanta in the City of Atlanta 1 Acknowledgements Project Team: Principal Investigator: Anthony J. Giarrusso, Associate Director, Senior Research Scientist Center for Spatial Planning Analytics and Visualization ( Georgia Institute of Technology 760 Spring Street, Suite 230 Atlanta, GA 30308 Office: 404-894-0127 [email protected] Graduate Research Assistant Jeremy Nichols Center for Spatial Planning Analytics and Visualization Georgia Institute of Technology 760 Spring Street, Suite 230 Atlanta, GA 30308 The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the City of Atlanta. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The project team would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals for their assistance on this project. Kathryn A. Evans, Senior Administrative Analyst, Tree Conservation Commission, Department of Planning and Development, Arborist Division Assessing Urban Tree Cover in the City of Atlanta The 2014 Canopy -

4 Corners/Stanton Development Option

Appendix 5 Atlanta BeltLine Master Plan SUBAREA 2 Heritage Communities of South Atlanta PEOPLESTOWN PARKS MASTER PLAN Prepared for Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. by Tunnell-Spangler-Walsh & Associates with Smith Dalia Architects Adopted by the Atlanta City Council on March 16, 2009 this page left intentionally blank this report has been formatted to be printed double-sided in an effort to save paper ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Honorable Mayor Shirley Franklin ATLANTA CITY COUNCIL Lisa Borders, President Clara Axam, Enterprise Community Partners, Inc.; MARTA Board of Directors Carla Smith, District 1 Ray Weeks, Chair of the BeltLine Partnership Board; CEO, Kwanza Hall, District 2 Weeks Properties Ivory Lee Young, Jr., District 3 Elizabeth “Liz” Coyle, Community Representative Cleta Winslow, District 4 SUBAREA 2 STEERING COMMITTEE Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 George Dusenbury, Park Pride Anne Fauver, District 6 LaShawn M. Hoffman, NPU V Howard Shook, District 7 Shauna Mettee, Capitol View Manor Neighborhood Clair Muller, District 8 Mtamanika Youngblood, Annie E. Casey Foundation Felicia A. Moore, District 9 Donna Tyler, CAMP CDC C.T. Martin, District 10 Tiffany Thrasher, Resident Jim Maddox, District 11 Steve Holland, Capitol View Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Helen Jenkins, Pittsburgh Community Improvement Ceasar C. Mitchell, Post 1 at Large Association Mary Norwood, Post 2 at Large John Armour, Peoplestown H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 at Large Rosa Harden-Green, SW Study Group Coordinator Jared Bagby, Peoplestown ATLANTA BELTLINE, INC. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mike Wirsching, Adair Park Neighborhood Calvin “Cal” Darden, Chair Greg Burson, Peoplestown The Honorable Shirley Franklin, Vice Chair, City of Atlanta Mayor Carl Towns, Pittsburgh Civic League The Honorable Jim Maddox, Atlanta City Council District 11 Chrishette Carter, Chosewood Park Neighborhood Association Joseph A. -

Preliminary Working Draft of FORMER City of Atlanta Street Names

Preliminary Working Draft of EXISTING City of Atlanta Street Names Associated with the Confederacy as of November 2, 2017 Current Name Location in City Preliminary Notes Cleburne Avenue Inman Park Named after Patrick R. Cleburn, an Irish-born Confederate General who fought at Shiloh, Chickamauga, and throughout the Chattanooga and Atlanta campaigns. Cleburne Terrace Inman Park Named after Patrick R. Cleburn, an Irish-born Confederate General who fought at Shiloh, Chickamauga, and throughout the Chattanooga and Atlanta campaigns. Confederate Avenue Grant Park / Ormewood Park Named after the former Confederate Soldier's Home, which was completed in 1900 and once stood on the current site of the Georgia Emergency Management complex - site of the former Shultz Farm East Confederate Avenue Grant Park / Ormewood Park Named after the former Confederate Soldier's Home, which was completed in 1900 and once stood on the current site of the Georgia Emergency Management complex - site of the former Shultz Farm Forrest Street Named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate Army General and founder of the Ku Klux Klan Gordon Place West End Named after the former Confederate General John B. Gordon. Gordon became the first Democratic governor of Georgia after the Civil War, bringing an end to Reconstruction Era Republican control of the state. Hardee Circle Kirkwood Continuation of Hardee Street, which is named after Confederate General William J. Hardee Hardee Street Reynoldstown / Kirkwood / Edgewood Named after Confederate General William J. Hardee Holtzclaw Street Reynoldstown Named after Confederate General (and McDonough, GA native) James T. Holtzclaw who commanded forces during the Chattanooga and Atlanta campaigns Lee Street southwest Atlanta Most likely named after Confederate General Robert E. -

Atlanta Neighborhoods : Grady Memorial Hospital Is Located in Area

Atlanta Neighborhoods1: 1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlanta_neighborhoods 1. Fairlie-Poplar 15. Berkeley Park 28. Edgewood 2. Downtown 16. Atlantic Station 29. Kirkwood 3. Castleberry Hill 17. Ansley Park 30. East Atlanta 4. West End 18. Buckhead 31. Ormewood Park 5. Vine City 19. Morningside- 32. Thomasville 6. Home Park Lenox Park 33. Lakewood Heights 7. Midtown 20. Virginia Highland 34. Oakland City 8. Old Fourth Ward 21. Druid Hills 35. Adams Park 9. Sweet Auburn 22. Poncey Highland 36. Sandtown 10. Grant Park 23. Inman Park 37. Ben Hill 11. Peoplestown 24. Candler Park 38. Adamsville 12. Mechanicsville 25. Lake Claire 39. Cascade Heights 13. Adair Park 26. Cabbage Town 40. Grove Park 14. Bankhead 27. Reynoldstown 41. Center Hill Grady Memorial Hospital is located in area 1 just north of the intersection of I-75/85 and I-20. Emory University is located in Area 21, Druid Hills. Driving Distance from Grady to Emory ~15 minutes. www.promove.com is an excellent resource for locating apartments in Atlanta. Popular Areas Where Residents Live: 7 Midtown Distance from Grady: 10-15 minutes Distance from Emory: 10-15 minutes Cost: $$ range from 750-1000 for one bedroom apartment Attractions: Arts Center of Atlanta. Home of the Fox Theater, High Museum of Art, and Alliance Theater. Walking distance from several restaurants and popular lounges. 21 Druid Hills Distance from Grady: 15 – 20 minutes Distance from Emory: 5-10 minutes Cost: $$-$$$ from 750-1000 for one bedroom apartment Attractions: Close to Emory, Piedmont Park, many quant outdoor shopping districts. Many suburbia neighborhoods and great bike paths. -

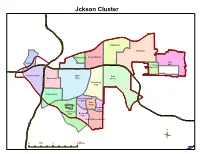

Jckson Cluster

Jckson Cluster Edgewood Kirkwood Cabbagetown Reynoldstown East Castleberry Lake Hill The Villages at East Lake Mechanicsville Grant East Summerhill Park Atlanta Ormewood Park Peoplestown Boulevard Heights State Englewood Facility Manor Woodland Hills Chosewood Park Benteen Park 20 Custer/McDonough/Guice ¨¦§ ¨¦§75 Ü 0 0.5 1 2 Miles ¨¦§285 No. of APS students by Place of Residence 1‐Apr‐15 Grade Neighborhood Total KK 01 02 03 04 05 Benteen Park 8 7 11 10 7 13 56 Boulevard Heights 13 7798549 Cabbagetown 4111 18 Castleberry Hill 1 1 Chosewood Park 21 24 13 21 20 22 121 Custer/McDonough/Guice 30 30 30 35 18 21 164 East Atlanta 49 46 47 55 37 29 263 East Lake 33 27 27 25 22 15 149 Edgewood 54 50 48 41 44 42 279 Grant Park 86 70 71 62 61 56 406 Kirkwood 67 56 69 54 42 32 320 Mechanicsville 88 84 75 73 57 47 424 Ormewood Park 64 70 61 45 49 41 330 Peoplestown 52 45 52 50 52 38 289 Reynoldstown 10 6 17 11 8 13 65 Summerhill 31 21 33 31 33 21 170 The Villages at East Lake 41 37 46 31 39 29 223 Woodland Hills 52522521 Total 657 583 613 556 499 430 3,338 No. of APS students by Place of Residence and School Enrolled 1‐Apr‐15 Grade Neighborhood School Total KK 01 02 03 04 05 Benteen Park ANCS 211 4 Benteen Park Benteen Elementary School 54572730 Benteen Park Burgess‐Peterson Elementary School 1 1 Benteen Park Parkside Elementary School 1 1 Boulevard Heights ANCS 2 133 9 Boulevard Heights Benteen Elementary School 2 2 1 5 Boulevard Heights Parkside Elementary School 85372227 Cabbagetown ANCS 1 1 Cabbagetown Parkside Elementary School 1 1 2 Chosewood Park ANCS 1211 1 6 Chosewood Park Benteen Elementary School 1718817141589 Chosewood Park Burgess‐Peterson Elementary School 1 1 2 Chosewood Park Daniel H. -

YORK, JAKE ADAM. Jake Adam York Papers, 1972-2012

YORK, JAKE ADAM. Jake Adam York papers, 1972-2012 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: York, Jake Adam. Title: Jake Adam York papers, 1972-2012 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1376 Extent: 21 linear feet (21 boxes), 2 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box), 1 linear foot (1 box) born digital (BD), and 3 long play (LP) record boxes Abstract: The collection consists of the papers of poet, Jake Adam York, including poetry, research files, publications, professional and educational files, and personal correspondence. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance for access to unprocessed born digital materials in this collection. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to unprocessed born digital materials.