Ehrlichiosis Epidemiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ehrlichiosis in Dogs Animal Veterinary Associations Borne Diseases

21 Working ECAVA F F A E V C A A C V Group on E A F F A E V C Canine A FECAVA Federation of European Companion vector Ehrlichiosis in dogs Animal Veterinary Associations borne diseases WERSJA POPRAWIONA A Ehrlichia spp. !! Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne disease caused by Ehrlichia spp, an obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium of the Anaplasmataceae family. In Europe, Ehrlichia canis causes canine monocytic ehrlichiosis ! (CME) The tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus is its main vector in Europe. Dogs and wild canids act as reservoirs. The disease has a subclinical, acute asymptomatic phase and chronic phase. The prognosis for chronically sick dogs is poor, ! !! The incubation period is 1-4 weeks. German Shepherds and Siberian Huskies appear to be more susceptible to clinical ehrlichiosis with more severe clinical !! presentations than other breeds. When to suspect infection? Origin / travelling history Clinical signs o Dogs that live in, originate from or have travelled to countries where the parasite is endemic are at risk. Weight loss, anorexia, lethargy, fever o Dogs in countries not currently considered endemic Bleeding disorders: petechiae/ecchymoses of the skin, mucous o o should not be considered free of risk. membranes and conjunctivas, hyphaema, epistaxis Lymphadenomegaly o How can it be confirmed? o Splenomegaly o Ocular signs: conjunctivitis, uveitis, corneal oedema Blood smear: Visualisation of intracellular bacteria on blood o Neurological signs (less common): seizures, ataxia, paresis, smears stained with Giemsa or similar. Sensitivity is poor: hyperaesthesia, cranial nerve deficits E. canis morulae in monocytes are visualised in only 4% (meningitis/meninigoencephalitis) cases of acute infections. -

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis What is ehrlichiosis and can also have a wide range of signs Who should I contact, if I what causes it? including loss of appetite, weight suspect ehrlichiosis? Ehrlichiosis (air-lick-ee-OH-sis) is a loss, prolonged fever, weakness, and In Animals – group of similar diseases caused by bleeding disorders. Contact your veterinarian. In Humans – several different bacteria that attack Can I get ehrlichiosis? the body’s white blood cells (cells Contact your physician. Yes. People can become infected involved in the immune system that with ehrlichiosis if they are bitten by How can I protect my animal help protect against disease). The an infected tick (vector). The disease organisms that cause ehrlichiosis are from ehrlichiosis? is not spread by direct contact with found throughout the world and are Ehrlichiosis is best prevented by infected animals. However, animals spread by infected ticks. Symptoms in controlling ticks. Inspect your pet can be carriers of ticks with the animals and humans can range from frequently for the presence of ticks bacteria and bring them into contact mild, flu-like illness (fever, body aches) and remove them promptly if found. with humans. Ehrlichiosis can also to severe, possibly fatal disease. Contact your veterinarian for effective be transmitted through blood tick control products to use on What animals get transfusions, but this is rare. your animal. ehrlichiosis? Disease in humans varies from How can I protect myself Many animals can be affected by mild infection to severe, possibly fatal ehrlichiosis, although the specific infection. Symptoms may include from ehrlichiosis? bacteria involved may vary with the flu-like signs (chills, body aches and The risk for infection is decreased animal species. -

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Weekly March 20, 2009 / Vol

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report www.cdc.gov/mmwr Weekly March 20, 2009 / Vol. 58 / No. 10 Trends in Tuberculosis — World TB Day — March 24, 2009 United States, 2008 World TB Day is observed each year on March 24 to commemorate the date in 1882 when Dr. Robert Koch In 2008, a total of 12,898 incident tuberculosis (TB) cases announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the were reported in the United States; the TB rate declined 3.8% bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). Worldwide, TB from 2007 to 4.2 cases per 100,000 population, the lowest remains one of the leading causes of death from infectious rate recorded since national reporting began in 1953. This disease. An estimated 2 billion persons are infected with report summarizes provisional 2008 data from the National M. tuberculosis (1). In 2006, approximately 9.2 million TB Surveillance System and describes trends since 1993. persons became ill from TB, and 1.7 million died from Despite this overall improvement, progress has slowed in the disease (1). World TB Day provides an opportunity recent years; the average annual percentage decline in the TB for TB programs, nongovernmental organizations, and rate decreased from 7.3% per year during 1993–2000 to 3.8% other partners to describe problems and solutions related during 2000–2008.* Foreign-born persons and racial/ethnic to the TB pandemic and to support worldwide TB minorities continued to bear a disproportionate burden of TB control efforts. The U.S. theme for this year’s observance disease in the United States. In 2008, the TB rate in foreign- is Partnerships for TB Elimination. -

2012 Case Definitions Infectious Disease

Arizona Department of Health Services Case Definitions for Reportable Communicable Morbidities 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Definition of Terms Used in Case Classification .......................................................................................................... 6 Definition of Bi-national Case ............................................................................................................................................. 7 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ............................................... 7 AMEBIASIS ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ANTHRAX (β) ......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 ASEPTIC MENINGITIS (viral) ......................................................................................................................................... 11 BASIDIOBOLOMYCOSIS ................................................................................................................................................. 12 BOTULISM, FOODBORNE (β) ....................................................................................................................................... 13 BOTULISM, INFANT (β) ................................................................................................................................................... -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Ehrlichia Ewingii Sp. Nov., the Etiologic Agent of Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEMATICBACTERIOLOGY, Apr. 1992, p. 299-302 Vol. 42, No. 2 0020-7713/92/020299-04$02.00/0 Copyright 0 1992, International Union of Microbiological Societies NOTES Ehrlichia ewingii sp. nov., the Etiologic Agent of Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis BURT E. ANDERSON,l* CRAIG E. GREENE,2 DANA C. JONES,l AND JACQUELINE E. DAWSON’ viral and Rickettsial Zoonoses Branch, Division of viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia 30333, and Department of Small Animal Medicine, College of Veterinaly Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 306022 The 16s rRNA gene was amplified, cloned, and sequenced from the blood of two dogs that were experimentally infected with the etiologic agent of canine granulocytic ehrlichiosis. The 16s rRNA sequence was found to be unique when it was compared with the sequences of other members of the genus Ehrlichia. The most closely related species were Ehrlichia canis (98.0% related) and the human ehrlichiosis agent (Ehrlichia chafeensis) (98.1% related); all other species in the genus were found to be phylogenetically much more distant. Our results, coupled with previous serologic data, provide conclusive evidence that the canine granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent is a new species of the genus Ehrlichia that is related to, but is distinct from, E. canis and all other members of the genus. We propose the name Ehrlichia ewingii sp. nov.; the Stillwater strain is the type strain. Ehrlichia canis, the type species of the genus Ehrlichia, human ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chafeensis) (1) is discussed was first described by Donatien and Lestoquard in 1935 (7). -

Exploration of Tick-Borne Pathogens and Microbiota of Dog Ticks Collected at Potchefstroom Animal Welfare Society

Exploration of tick-borne pathogens and microbiota of dog ticks collected at Potchefstroom Animal Welfare Society C Van Wyk orcid.org 0000-0002-5971-4396 Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Environmental Sciences at the North-West University Supervisor: Prof MMO Thekisoe Co-supervisor: Ms K Mtshali Graduation May 2019 24263524 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the late Nettie Coetzee. For her inspiration and lessons to overcome any obstacle that life may present. God called home another angel we all love and miss you. “We are the scientists, trying to make sense of the stars inside us.” -Christopher Poindexter i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest appreciation goes out to my supervisor, Prof. Oriel M.M. Thekisoe, for his support, motivation, guidance, and insightfulness during the duration of this project and been there every step of the way. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, Ms. Khethiwe Mtshali, for her patience and insightfulness towards the corrections of this thesis. I would like to thank Dr. Stalone Terera and the staff members at PAWS for their aid towards the collection of tick specimens. For the sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform and metagenomic data analysis I would like to thank Dr. Moeti O. Taioe, Dr. Charlotte M.S. Mienie, Dr. Danie C. La Grange, and Dr. Marlin J. Mert. I would like to thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) for their financial support by awarding me the S&F- Innovation Masters Scholarship and the North-West University (NWU) for the use of their laboratories. -

Canine Ehrliciosis in Australia

Canine ehrlichiosis in Australia Fact sheet Introductory statement Australia was previously believed to be free of Ehrlichia canis. During 2020, the organism was detected in Australian dogs for the first time. Infection with E. canis (ehrlichiosis) is a notifiable disease in Australia. If you suspect ehrlichiosis in Australia, call the Emergency Animal Disease hotline on 1800 675 888. The disease is also known as canine monocytic ehrlichiosis and can cause serious illness and death in dogs. Aetiology The organism Ehrlichia canis, is an obligate gram negative intracellular rickettsial bacterium belonging to the family Anaplasmataceae. It is transmitted through tick bites, in particular the bite of the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus). Natural hosts Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are considered the natural hosts of the organism. Other canids such as foxes and wolves are known to become infected with the bacterium (Santoro et al. 2016). It is assumed that dingos, a uniquely Australian ancient dog breed which some people consider a different species to domestic and wild dogs, may also become infected, and may be susceptible to disease from E. canis. On rare occasions, humans or cats can become infected from a tick bite (Stich et al. 2008; Day 2011). World distribution E. canis occurs worldwide, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. It was, until recently, considered to be absent from Australia. Occurrences in Australia In 2020, E. canis was detected in Western Australia and the Northern Territory. It was first detected in a small number of domesticated dogs in the Kimberly region of WA in May 2020. This was the first detection of ehrlichiosis in dogs in Australia outside of dogs that had been imported from overseas. -

Human Babesiosis and Ehrlichiosis Current Status

IgeneX_v1_A4_A4_2011 27/04/2012 17:26 Page 49 Tick-borne Infectious Disease Human Babesiosis and Ehrlichiosis – Current Status Jyotsna S Shah,1 Richard Horowitz2 and Nick S Harris3 1. Vice President, IGeneX Inc., California; 2. Medical Director, Hudson Valley Healing Arts Center, New York; 3. CEO and President, IGeneX Inc., California, US Abstract Lyme disease (LD), caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi complex, is the most frequently reported arthropod-borne infection in North America and Europe. The ticks that transmit LD also carry other pathogens. The two most common co-infections in patients with LD are babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Human babesiosis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Babesia including Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia divergens, Babesia divergens-like (also known as Babesia MOI), Babesia EU1 and Babesia KO1. Ehrlichiosis includes human sennetsu ehrlichiosis (HSE), human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), human ewingii ehrlichiosis (HEE) and the recently discovered human ehrlichiosis Wisconsin–Minnesota (HWME). The resulting illnesses vary from asymptomatic to severe, leading to significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Clinical signs and symptoms are often non-specific and require the medical provider to have a high degree of suspicion of these infections in order to be recognised. In this article, the causative agents, geographical distribution, clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment protocols are discussed for both babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Keywords Babesia, Ehrlichia, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, human, Borrelia Disclosure: Jyotsna Shah and Nick Harris are employees of IGeneX. Richard Horowitz is an employee of Hudson Valley Healing Arts Center. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Eddie Caoili, and Sohini Stone, for providing technical assistance. -

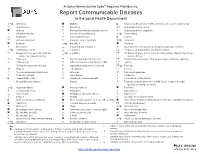

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

Canine Ehrlichiosis: Update

Canine Ehrlichiosis: Update Barbara Qurollo, MS, DVM ([email protected]) Vector-Borne Disease Diagnostic Laboratory Dep. Clinical Sciences-College of Veterinary Medicine North Carolina State University Overview Ehrlichia species are tick-transmitted, obligate intracellular bacteria that can cause granulocytic or monocytic ehrlichiosis. Ehlrichia species that have been detected in the blood and tissues of clinically ill dogs in North America include Ehrlichia canis, E. chaffeenis, E. ewingii, E. muris and Panola Mountain Ehrlichia species (Table 1). Clinicopathologic abnormalities reported in dogs with ehrlichiosis vary depending on the species of Ehrlichia, strain variances and the immune or health status of the dog. The course of disease may present as subclinical, acute, chronic or even result in death (Table 1). E. canis and E. ewingii are the most prevalent and frequently described Ehrlichia infections in dogs. E. canis: Transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, E. canis is found world-wide. Within North America, the highest seroprevalence rates have been reported in the Southern U. S.2, 12 E. canis typically infects canine mononuclear cells. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME) is characterized by 3 stages: acute, subclinical and chronic. Following an incubation period of 1-3 weeks, infected dogs may remain subclinical or present with nonspecific signs including fever, lethargy, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, lameness, edema, bleeding disorders and mucopurulent ocular discharge. Less commonly reported nonspecific signs include vomiting, diarrhea, coughing and dyspnea. Bleeding disorders can include epistaxis, petechiae, ecchymoses, gingival bleeding and melena. Ocular abnormalities identified in E. canis infected dogs have included anterior uveitis, corneal opacity, retinal hemorrhage, hyphema, chorioretinal lesions and tortuous retinal vessels.8 Following an acute phase (2-4 weeks), clinical signs may resolve without treatment and the dog could remain subclinically infected indefinitely or naturally clear the pathogen. -

Using Core Genome Alignments to Assign Bacterial Species 2

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/328021; this version posted May 22, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Using Core Genome Alignments to Assign Bacterial Species 2 3 Matthew Chunga,b, James B. Munroa, Julie C. Dunning Hotoppa,b,c,# 4 a Institute for Genome Sciences, University of Maryland Baltimore, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA 5 b Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland Baltimore, Baltimore, MD 6 21201, USA 7 c Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Maryland Baltimore, Baltimore, MD 21201, 8 USA 9 10 Running Title: Core Genome Alignments to Assign Bacterial Species 11 12 #Address correspondence to Julie C. Dunning Hotopp, [email protected]. 13 14 Word count Abstract: 371 words 15 Word count Text: 4,833 words 16 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/328021; this version posted May 22, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 17 ABSTRACT 18 With the exponential increase in the number of bacterial taxa with genome sequence data, a new 19 standardized method is needed to assign bacterial species designations using genomic data that is 20 consistent with the classically-obtained taxonomy.