Early Dutch Settlements in South Dakota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rewind, Play, Fast Forward : the Past, Present and Future of the Music Video, Bielefeld 2010, S

Originalveröffentlichung in: Keazor, Henry ; Wübbena, Thorsten (Hrsgg.): Rewind, play, fast forward : the past, present and future of the music video, Bielefeld 2010, S. 7-31 Rewind - Play - Fast Forward The Past, Present and Future of the Music Video: Introduction HENRY KEAZOR/THORSTEN WUBBENA "Art presses the "Stop"- and "Rewind"- buttons in the stream of life: It makes time stop. It offers reflection and re collection, it is an antidote against lost certitudes."1 Like perhaps no other medium, the music video clip is marking and shap ing our everyday culture: film, art, literature, advertisements they all are clearly under the impact of the music video in their aesthetics, their technical procedures, visual worlds or narrative strategies. The reason for this has not only to be sought in the fact that some of the video di rectors are now venturing into art or advertisement, but that also peo ple not working in the field of producing video clips are indebted to this medium.2 Thus, more or less former video clipdirectors such as Chris Cunningham or Jonas Akerlund have established themselves successfully with their creations which very often are based on ideas and concepts, originally developed for earlier music videos: both Cunningham's works Flex and Monkey Drummer, commissioned in 2000 respectively 2001 by the Anthony d'Offay Gallery, evolved out of his earlier music videos.' Flex relies on the fantastic and weightless underwater cosmos Cunningham designed for the images that accompanied Portishead's Only you in 1998. Monkey Drummer* is heavily based on the soundtrack written by the Irish musician Aphex Twin (Richard David James) for whom Cunningham had previously directed famous videos such as Come to Daddy (1997) and Win- dowlicker (1999). -

Simon and Garfunkel the Concert in Central Park

You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING Simon and The concert Simon and The concert Simon and The concert Garfunkel in Central Park Garfunkel in Central Park Garfunkel in Central Park 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 Humph Hall Humph Hall Humph Hall 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Scarborough Fair, Wake Up Little Suzie, Still Crazy After All These Scarborough Fair, Wake Up Little Suzie, Still Crazy After All These Scarborough Fair, -

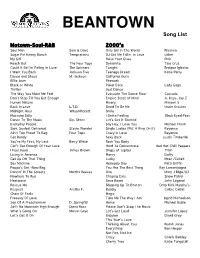

Beantown Song List 2010

BEANTOWN Song List Motown-Soul-R&B 2000’s Soul Man Sam & Dave Only Girl In The World Rhianna Sugar Pie Honey Bunch Temptations DJ Got Me Fallin in Love Usher My Girl Raise Your Glass Pink Reach Out The Four Tops Dynamite Taio Cruz Could It Be I’m Falling In Love The Spinners Tonight Enrique Iglesias I Want You Back Jackson Five Teenage Dream Katie Perry Dance and Shout M. Jackson California Gurls Billie Jean FIrework Black or White Poker Face Lady Gaga Thriller Just Dance The Way You Make Me Feel Evacuate The Dance Floor Cascada Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough Empire State of Mind A. Keys, Jay Z Human Nature Misery Maroon 5 Back In Love L.T.D. Good To Be Me Uncle Kracker Midnight Hour WilsonPickett Smile Mustang Sally I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Dance To The Music Sly. Stone Let’s Get It Started Everyday People Say Hey, I Love You Michael Franti Sign, Sealed, Delivered Stevie Wonder Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) Beyonce Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Four Tops Crazy In Love Beyonce Get Ready Sexy Back Justin Timberlak You’re My First, My Last Barry White Rock You Body Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love Hard To Concentrate Red Hot Chilli Peppers I Feel Good James Brown Drops of Jupiter Train Living In America Mercy Duffy Get Up Off That Thing Lucky Mraz /Collait Sex Machine Heavenly Day Patti Griffin Poppa’s Got -New Bag You Are The Best Thing Ray Lamontaigne Dancin’ In The Streets Martha Reeves One Mary J Blige/U2 Nowhere To Run Chasing Cars Snow Patrol Heatwave Save Room John Legend Rescue Me Shipping Up To Boston Drop Kick Murphy’s Respect Aretha F. -

Service ~Abrams Blends Puppets and Culture

~ Abrams blends puppets and culture BY BOB YATES ECREditor In an on-going effort to blend culture and entertainment, the Noon Hour Concert Series tomorrow will present "Folk Heroes of the Puppet Stage." The performance will be given by professional puppeteer Steven Abrams and his associates from Philadelphia. Abrams has been presenting puppet shows for over 15 years all across the nation. In 1972 and again in 1974 he performed at the Library and Museum ofthe Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. Abrams has displayed his talent in numerous parks, libraries, and has even performed on Indian reservations. The show while amusing and entertaining, is actually a history of the puppet stage. Abrams traces the long tradition of puppetering from the sketch "Shiva and the Toy-maker," an Indian marionette act from the fifth century B.C., to . "Guignol" a French hand puppet that first appeared in 1815. Some ofthe other sketches to be performed include "Dance of Four" and act by Japanese Bunraku puppets, an appearance by th~ Russian puppets "Ivan and Petrushka," and a performance of the traditional "Punch and Judy" skit. AJ:>rams and his associates will give their show tomorrow at noon III the Jefferson Hall auditorium_ Admission is free. BY CHARLES HAGEE compositions in an atmosphere of total ECR Staff enthusiasm. From the opening chords of It's amazing how something of quality "Mrs. Robinson" all the way through to the doesn't tarnish with the passing of time. final sigh of the "Sounds of Silence" you can't Moreover, quality is a trait that is seemingly help but feel that the performers are enjoying lacking in much of today's music. -

UPERCHARTS! See Billboard's Traffic Center Inside BB049GREENLYMONT 00 MONTY GREENLY MARG I NEWSPAPER 374J ELM

UPERCHARTS! See Billboard's Traffic Center Inside BB049GREENLYMONT 00 MONTY GREENLY MARG I NEWSPAPER 374J ELM LONG BEACH CA 93807 A Billboard Publication The Radio Programming, Music /Record International Newsweekly Two Sections, Section One August 9, 1980 $3.00 (U.S.) Costs Peril Canadian & Rising Single Prices U.K. Charts Hurt U.S. Jukeboxes By ALAN PENCHANSKY This story prepared by Adam White in New York and David Farrell in Toronto. CHICAGO -Recent WEA and Capitol sin- NEW YORK -The cost of producing re- AFTRA Strike Leads gles price increases are hitting U.S. jukebox liable record charts has become prohibitive in operators during a period of rapidly mounting two key world markets. cost pressures, causing deepening concern In Canada, the local disk industry associ- To Label Fee Buildup about the overall health of the jukebox indus- ation has discontinued its weekly top 50 sin- By IS HOROWITZ try. gles and album charts due to "increased pro- NEW YORK -Record companies are fast The $1.69 list singles pricing comes at the duction costs" and to the cancellation of a accumulating a retroactive obligation to sing- same time that operators are bracing for an an- television music program which contributed ers performing on disk. as aborted talks with ticipated sizable increase in the copyright li- towards those costs. the American Federation of Television & Ra- cense fee, a combination of factors that some In Britain, the local disk industry association Laser Record: AMA's new "True Colours" LP dio Artists on home video prevent implemen- feel will lead to an acceleration of the ongoing has put its chart contract out for bids, hoping by New Zealand band Split Enz features a la- tation of recording terms already agreed upon. -

Nate Jones Song List C/O CLE Music Group

Nate Jones Song List c/o CLE Music Group PRIVATE EVENT SONG LIST Alicia Keys “No One” Allman Brothers Band “Midnight Rider” America “Horse with No Name” “Ventura Highway” Amos Lee “Sweet Pea” “Keep It Loose, Keep It Tight” ”Windows are Rolled Down” Arlo Guthrie ”City of New Orleans” “Coming into Los Angeles” “Darkest Hour” Art Garfunkel “All I Know” “A Heart In New York” Badfinger “Day After Day” “No Matter What” The Band “Ophelia” “The Weight” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” The Beatles “Yesterday” “In My Life” “Here, There and Everywhere” “When I’m Sixty-Four” “Strawberry Fields Forever” “Blackbird” “Dear Prudence” “Julia” “Rocky Raccoon” “I Will” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” “Mother Nature’s Son” “Revolution No. 1” “Honey Pie” “Hey Jude” “Let It Be” “Get Back” “The Long and Winding Road” “Come Together” “Something” “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” “Oh! Darling” “Here Comes The Sun” Bill Withers “Lean On Me” “Ain’t No Sunshine” “Use Me” Billy Joel “Piano Man” “Only the Good Die Young” “Movin’ Out” “Just the Way You Are” “She’s Always a Woman” “My Life” “She’s Got A Way” “Miami 2017 (Seen The Lights Go Out on Broadway)” “Honesty” “Everybody Loves You Now” “Don’t Ask Me Why” “You’re My Home” “Through the Long Night” “An Innocent Man” “The Longest Time” The Black Keys “Tighten Up” Blind Faith “Can’t Find My Way Home” “Presence of the Lord” Blues Traveler “Run-Around” “Hook” Bob Dylan “Don't Think Twice (It’s Alright)” “I Shall Be Released” “Mr. Tambourine Man” “Like a Rolling Stone” “Tangled Up in Blue” “Shelter From the Storm” Bob Seger “Turn the Page” “Still The Same” Bonnie Raitt “Something to Talk About” Bread “Everything I Own” “The Guitar Man” Buffalo Springfield “For What It’s Worth” “Mr. -

Detection of Genuine Lossless Audio Files. Application to the MPEG-AAC

PRISM CNRS, TECHNICAL REPORT 1 Detection of genuine lossless audio files. Application to the MPEG-AAC codec. Detailed results. Olivier Derrien A. INTRODUCTION This report is a complementary document for the paper submitted to the Journal of Audio Engineering Society: ”Detection of genuine lossless audio files. Application to the MPEG-AAC codec.” In this document, we give all detailed results, both on the small and large audio databases. Please refer to the paper for further details. B. DETAILED RESULTS ON THE SMALL AUDIO DATABASE A. Description of the database The database is composed of 10 individual audio files, ripped from commercial CDs. The files are described in table I. Id Artist Title Album Genre Cocaine J.J. Cale Cocaine Troubadour Blues/Rock Goldberg Variation n.10 J.S. Bach Variation n.10 Goldberg Variations (G. Gould 1981) Classical/piano Evening Paul Simon Late in the Evening One-Trick Pony Pop/worldbeat Fandango Antonio Soler Fandango Variaciones del Fandango Espanol˜ (A. Steier) Classical/harpischord Hold on Johnny Copeland Hold on to What You’ve Got Jungle Swing Blues Messiah G.F. Handel And the Glory of the Lord Messiah (W. Christie 1993) Classical/vocal Revolution Tracy Chapman Talkin’ About Revolution Tracy Chapman Folk Rose Rouge Saint Germain Rose Rouge Tourist Electro Sentimental Sonny Rollins In a Sentimental Mood Sonny Rollins with the Modern Jazz Quartet Jazz Symphony L.v. Beethoven 1st movement - Allegro 6th Symphony (H.v. Karajan 1976) Classical/symphony TABLE I DESCRIPTION OF THE AUDIO FILES IN THE SHORT DATABASE. B. Distribution of relative scalefactors In order to tune the detector, we analyze the distribution of relative scalefactors (i.e. -

Michael Murphy Song List 2018

Michael Murphy song list 2018 TITLE ARTIST A horse with no name America Amie Pure Prarie league American girl Tom Petty And it Stoned Me Van Morrison Babylon David Grey Bad bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Bad Moon Rising CCR Beg Steal borrow Ray Lamontagne Bertha Grateful Dead Better man Pearl Jam Big empty Stone temple pilots Black Pearl jam Black water Doobie brothers Blister in the sun Violent femmes Blue sky Allman brothers Boxer Paul Simon Brian wilson Barenakedladies Brown eyed girl van Morrison Cest la vie Chuck berry Can’t you see Marshal Tucker Carolina in my mind James Taylor Cecilia Simon garfunkel Centerfield Jon fogerty Cherry bomb John Mellencamp Clocks Cold play Closer to fine Indigo girls Come monday Jimmy buffet Come together Beatles Cough syrup Young the giant Country roads John denver Creep Radiohead Crazy Gnarls Barkley Dance dance dance Steve miller Daniel Elton john Danny’s song Kenny loggins Danny boy Irish trad Dead flowers Rolling stones Desperado Eagles Dirty old town Irish trad. Dock of the bay Otis redding 1 Michael Murphy song list 2018 Doctor my eyes Jackson brown Don’t ask me why Billie Joel Down by the river Neil Young Down on the corner Ccr Drift away Dover grey Drive Incubus Drops of Jupiter Train Drunken Sailor Irish trad Elderly woman.. Pearl jam End of the innocence Henley/Hornsby End of the line Traveling Willburies Fairy tale of NY Pogues Father and Son Jim Croce Feelin alright Joe cocker Fields of gold Sting Fire and rain Janes taylor Folsom prison Johnny Cash For what it’s worth Buffalo Springfield Four green fiekds Irish trad. -

2019 YRR Song List

2019 Yacht Rock Revue Song List 1999- Prince 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover – Paul Simon Africa – Toto Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band All Night Long – Lionel Richie Arthur’s Theme — Christopher Cross Baby Come Back – Player Baker Street – Gerry Rafferty Brandy – Looking Glass Break My Stride- Matthew Wilder Call Me Al – Paul Simon Careless Whisper – Wham! Couldn’t Get It Right – Climax Blues Band Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest Don’t Stop- Fleetwood Mac Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Dreams- Fleetwood Mac Easy- Lionel Ritchie Escape (The Pina Colada Song) – Rupert Holmes Footloose – Kenny Loggins Give a Little Bit – Supertramp Go Your Own Way – Fleetwood Mac Greatest American Hero – Joey Scarbury Hey 19 – Steely Dan Heart to Heart- Kenny Loggins Hooked On A Feeling – BJ Thomas Hot Child In The City – Nick Gilder How Long – Ace I Can’t Go For That – Hall and Oates I Keep Forgettin’ – Michael McDonald I Love A Rainy Night — Eddie Rabbit I Wanna Be Your Lover – Prince I’m Alright – Kenny Loggins Islands In The Stream- The Bee Gees (Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton) Jive Talkin’ – The Bee Gees Kiss on My List – Hall & Oates Kodachrome – Paul Simon Late In The Evening- Paul Simon Let’s Dance – David Bowie Let’s Go Crazy - Prince Lady – The Commodores Lady — The Little River Band Lido Shuffle – Boz Scaggs Lotta Love – Nicolette Larson Love is Alive – Gary Wright Love Will Find A Way— Pablo Cruise Love Will Keep Us Together – Captain and Tenille Lovely Day – Bill Withers Lowdown – Boz Scaggs Maneater – Hall and Oates Me & Juilo- Paul -

February 5, 2018 Paul Simon Announces Homeward

FEBRUARY 5, 2018 PAUL SIMON ANNOUNCES HOMEWARD BOUND – THE FAREWELL TOUR Artist to stage ultimate concert performances in North America, UK and Europe, promising audiences an historic evening of career-spanning hits and timeless classics NEW YORK, February 5, 2018 – Legendary songwriter, recording artist and performer Paul Simon, will embark on his farewell concert tour on May 16 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada at Rogers Arena. Homeward Bound – The Farewell Tour will encompass shows across North America, the United Kingdom and Europe, with Simon and his band bringing to the stage a stunning, career-spanning repertoire of timeless hits and classic songs which have permeated and influenced popular culture for generations. Tickets for Paul Simon’s Homeward Bound – The Farewell Tour will go on sale beginning February. The complete tour itinerary is listed below. Go to PaulSimon.com for ticketing information as it becomes available. According to Simon, the Homeward Bound tour is a fitting culmination of a performing career that began in the early 1960s and has coincided with his artistic journey as a songwriter and recording artist until the present day. He said of this farewell tour, “I’ve often wondered what it would feel like to reach the point where I'd consider bringing my performing career to a natural end. Now I know: it feels a little unsettling, a touch exhilarating and something of a relief. I love making music, my voice is still strong, and my band is a tight, extraordinary group of gifted musicians. I think about music constantly. I am very grateful for a fulfilling career and, of course, most of all to the audiences who heard something in my music that touched their hearts.” - more – Having created a distinctive and beloved body of work that includes 13 studio albums, plus five studio albums as half of Simon & Garfunkel, Paul Simon is the recipient of 16 Grammy Awards, three of which—Bridge over Troubled Water, Still Crazy after All These Years, and Graceland— were Album of the Year honorees. -

Full Beacher

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 23, Number 28 Thursday, July 19, 2007 Eight Days of 4-H! at the 162nd LaPorte County Fair by Cherie Davich The 4-H Club has events all day, every day from Saturday, July 21st through Saturday, July 28th at the 162nd LaPorte County Fair, Indiana’s old- est fair. The following is a day by day breakdown of the forthcoming events, everything from scarecrow judging to Rockabilly entertainers. SATURDAY, JULY 21st The fair’s festivities will begin on Saturday July 21st at 8 a.m. with a rabbit show. The fl uffy little white-tailed creatures will be hopping their way 4-H Junior Leaders into spectators’ hearts. The rabbit exhibition is a soft way to set in motion eight days of animal ex- hibits, auctions, special events, music, and carnival rides. On this fi rst day, there will be a mini bicycle rodeo and the display of animals in the pet parade The soft and cuddly Rabbit Exhibit that should not be missed. SUNDAY, JULY 22nd The day starts at 9 a.m. on Sunday, July 22nd with not just any tractor pull, but an antique trac- tor pull. The added “pull and tug” is that there is no admission fee. For those who do not miss church on any given Sunday, a non-denominational church service will be held at the School House - Pioneer Land. There will not only be 4-H livestock view- ing, but needlepoint and hand-crafted creations to examine throughout the day. -

Franz Kafka the CASTLE IT Was Late in the Evening When K. Arrived, The

Franz Kafka THE CASTLE IT was late in the evening when K. arrived, The village was J. deep in snow. The Castle hill was hidden, veiled in mist and darkness, nor was there even a glimmer of light to show that a castle was there. On the wooden bridge leading from the main road to the village K. stood for a long time gazing into the illusory emptiness above him. Then he went on to find quarters for the night. The inn was still awake, and although the landlord could not provide a room and was upset by such a late and unexpected arrival, he was willing to let K. sleep on a bag of straw in the parlour. K. accepted the offer. Some peasants were still sitting over their beer, but he did not want to talk, and after himself fetching the bag of straw from the attic, lay down beside the stove. It was a warm corner, the peasants were quiet, and letting his weary eyes stray over them he soon fell asleep. But very shortly he was awakened. A young man dressed like a townsman, with the face of an actor, his eyes narrow and his eyebrows strongly marked, was standing beside him along with the landlord. The peasants were still in the room, and a few had turned their chairs round so as to see and hear better. The young man apologized very courteously for having awakened K., introducing himself as the son of the Castellan, and then said: "This village belongs to the Castle, and whoever lives here or passes the night here does so in a manner of speaking in the Castle itself.