Rewind, Play, Fast Forward : the Past, Present and Future of the Music Video, Bielefeld 2010, S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Call It Dreaming; Folk Rocker Iron & Wine to Play Qpac

28 March 2018 CALL IT DREAMING; FOLK ROCKER IRON & WINE TO PLAY QPAC American singer-songwriter Iron & Wine (aka Sam Beam) will make a long-awaited return to Australia with his new album and full band in tow, appearing for one night only at Queensland Performing Arts Centre’s (QPAC) Concert Hall on Wednesday 30 May 2018. Through the course of six studio albums, numerous EPs and singles, Iron & Wine has captured the emotion and imagination of listeners with distinctly cinematic songs. With a live band featuring acoustic guitars, percussion, keys, cello, and bass, Iron & Wine’s music has been compared to that of Nick Drake, Jackson Browne, Elliott Smith and Neil Young. From haunting, stripped-back performances alongside Glen Hansard to more panoramic collaborations with the likes of the Mariachi-wielding Calexico, Beam has rewritten his nom de plume as a sonic shape shifter ever-anchored by his signature high tenor voice - handpicked and introduced to millions by Kristen Stewart as the slow-dance soundtrack to Twilight. More than 15 years since his bedroom-folk breakthrough The Creek Drank the Cradle and his scene-stealing cover of Such Great Heights in Garden State, Beam will now lead a full band as Iron & Wine, taking to the Concert Hall stage for an expansive journey through his rustic masterpiece The Shepherd's Dog, the chart-topping Kiss Each Other Clean, R&B inflected Ghost on Ghost and his latest release 2017’s Grammy®-nominated album Beast Epic. Beam said the sound of Beast Epic, in a way, harked back to previous work. -

Early Dutch Settlements in South Dakota

EARLY DUTCH SETTLEMENTS IN SOUTH DAKOTA The first families came to this area from the Netherlands because economic conditions were such that there was no future for farmers and artisans. Wages were very low, both for the laboring class and the farmer. Many farmers had retrogressed to such an extent that they were forced to abandon their farms, and many workmen were unable to find employment. I recall that many carpenters complained about conditions, and they did not believe that it would be much better in the United States. Moreover, there were very few who had the means to pay for such a journey. Only those who had received some money from an inheritance began to think about emigrating. Rickele Zylstra, son of Je1le Zylstra, made plans to go to America with his family. I believe that he left during the latter part of 1881, and his brother Rein went with him, as well as a few families from Wolvega. The latter had acquaintances in BonHomme County, and all first went to that area. In 1882 these two sons of uncle Je1le went to Charles Mix County, and took up a claim. Riekele built a sod house for his family, but Rein returned to the Netherlands to be married. But alas, the girl of his choice refused to go to America, so Rein returned alone. In 1883 Douse, the third son of uncle Jelle, came here, and with him a family from the province of Groningan, namely 1. Dyksterhuis, with his wife, son, and two daughters. An older son had arrived a year earlier. -

2012 Morpheus Staff

2012 Morpheus Staff Editor-in-Chief Laura Van Valkenburgh Contest Director Lexie Pinkelman Layout & Design Director Brittany Cook Marketing Director Brittany Cook Cover Design Lemming Productions Merry the Wonder Cat appears courtesy of Sandy’s House-o-Cats. No animals were injured in the creation of this publication. Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 2 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 3 Table of Contents Morpheus Literary Competition Author Biographies...................5 3rd Place Winners.....................10 2nd Place Winners....................26 1st place Winners.....................43 Senior Writing Projects Author Biographies...................68 Brittany Cook...........................70 Lexie Pinkelman.......................109 Laura Van Valkenburgh...........140 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 4 Author Biographies Logan Burd Logan Burd is a junior English major from Tiffin, Ohio just trying to take advantage of any writing opportunity Heidelberg will allow. For “Onan on Hearing of his Broth- er’s Smiting,” Logan would like to thank Dr. Bill Reyer for helping in the revision process and Onan for making such a fas- cinating biblical tale. Erin Crenshaw Erin Crenshaw is a senior at Heidelberg. She is an English literature major. She writes. She dances. She prances. She leaps. She weeps. She sighs. She someday dies. Enjoy the Morpheus! Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 5 April Davidson April Davidson is a senior German major and English Writing minor from Cincin- nati, Ohio. She is the president of both the German Club and Brown/France Hall Council. She is also a member of Berg Events Council. After April graduates, she will be entering into a Masters program for German Studies. -

Besondere Leistungsfeststellung Deutsch

Sächsisches Staatsministerium Geltungsbereich: Schüler der Klassenstufe 10 an für Kultus allgemein bildenden Gymnasien Schuljahr 2005/2006 ohne Realschulabschluss Besondere Leistungsfeststellung Deutsch - N A C H T E R M I N - Material für Schüler Allgemeine Arbeitshinweise Es ist ein Thema zur Bearbeitung auszuwählen. Die Arbeitszeit beträgt 90 Minuten. Zur Auswahl der Aufgaben und der damit verbundenen Texte wird zusätzlich zur Arbeitszeit eine Einlesezeit von 20 Minuten gewährt. Zugelassenes Hilfsmittel: Wörterbuch der deutschen Rechtschreibung Die Arbeit wird mit einer ganzzahligen Note nach der Notenskala von 1 bis 6 bewertet. Gravierende Mängel in der äußeren Form werden bei der Notengebung berücksichtigt. Name, Vorname: Klasse: Note: Themen THEMA 1: Wir sind Helden/Text: Judith Holofernes (geb. 1976), „Guten Tag“ (2003) Interpretieren Sie den Liedtext. - Untersuchen Sie dabei den Sinngehalt. - Zeigen Sie, wie inhaltliche und sprachliche Gestaltung zusammenwirken. THEMA 2: Wolfgang Bächler (geb. 1925): Stadtbesetzung (1979) Interpretieren Sie den Text. - Untersuchen Sie dabei den Sinngehalt. - Zeigen Sie, wie inhaltliche und sprachliche Gestaltung zusammenwirken. Besondere Leistungsfeststellung Gymnasium, Klassenstufe 10, Deutsch, Nachtermin 2005/06 - Aufgaben Seite 1 von 3 Name, Vorname: _________________________________________________ Klasse: __ THEMA 1 Wir sind Helden/Text: Judith Holofernes Guten Tag (Die Reklamation) Meine Stimme gegen ein Mobiltelefon Meine Fäuste gegen eure Nagelpflegelotion Meine Zähne gegen die von Doktor -

Austrian Music Export Handbook

Austrian Music Export Handbook Table of Contents Imprint.................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction........................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 PART 1 - GENERAL INFORMATION.................................................................................................................................................... 7 Geogr p!ic l # t nd Tr n$port In%r $tructure.............................................................................................................. 7 Gener l In%ormation ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Town$ nd Citie$ ...................................................................................................................................................................... ( Admini$tr ti)e #i)i$ion$......................................................................................................................................................... * Tr n$port +Touring in Au$tri ,.............................................................................................................................................. * Import nt Cont ct$, Re" ted Lin.$ .............................................................................................................................. -

Exhibit O-137-DP

Contents 03 Chairman’s statement 06 Operating and Financial Review 32 Social responsibility 36 Board of Directors 38 Directors’ report 40 Corporate governance 44 Remuneration report Group financial statements 57 Group auditor’s report 58 Group consolidated income statement 60 Group consolidated balance sheet 61 Group consolidated statement of recognised income and expense 62 Group consolidated cash flow statement and note 63 Group accounting policies 66 Notes to the Group financial statements Company financial statements 91 Company auditor’s report 92 Company accounting policies 93 Company balance sheet and Notes to the Company financial statements Additional information 99 Group five year summary 100 Investor information The cover of this report features some of the year’s most successful artists and songwriters from EMI Music and EMI Music Publishing. EMI Music EMI Music is the recorded music division of EMI, and has a diverse roster of artists from across the world as well as an outstanding catalogue of recordings covering all music genres. Below are EMI Music’s top-selling artists and albums of the year.* Coldplay Robbie Williams Gorillaz KT Tunstall Keith Urban X&Y Intensive Care Demon Days Eye To The Telescope Be Here 9.9m 6.2m 5.9m 2.6m 2.5m The Rolling Korn Depeche Mode Trace Adkins RBD Stones SeeYou On The Playing The Angel Songs About Me Rebelde A Bigger Bang Other Side 1.6m 1.5m 1.5m 2.4m 1.8m Paul McCartney Dierks Bentley Radja Raphael Kate Bush Chaos And Creation Modern Day Drifter Langkah Baru Caravane Aerial In The Backyard 1.3m 1.2m 1.1m 1.1m 1.3m * All sales figures shown are for the 12 months ended 31 March 2006. -

Music Videos: the Look of the Sound by Pat Aufderheide

Music Videos Music Videos: The Look of the Sound by Pat Aufderheide Oflering an environment, an experience, a mood, “music videos have animated and set to music a tension basic to American youth culture: that feeling of instability which fuels the search to buy and belong. ’’ Music videos are more than a fad, more than fodder for spare hours and dollars of young consumers. They are pioneers in video expression, and the results of their reshaping of the form extend far beyond the TV set. Music videos have broken through TV’s most hallowed hound :i11es. .’ As commercials in themselves, they have erased the very distinction between the commercial and the program. As nonstop sequences of discontinuous episodes, they have erased the boundaries between programs. Music videos have also set themselves free fi-om the television set, inserting themselves into movie theaters, popping up in shopping nialls and department store windows, becoming actors in both live perfor- mances and the club scene. As omiiivorous as they are pervasive, they draw on and influence the traditional image-shaping fields offashion and advertising-even political campaigning. If‘ it sounds as if music video has a life of its own, this is not accidental. One of music video’s distinctive features as a social expres- Pat .4utilei-heidt~is cultural editor of‘ 111 T1ic.w Y’irnes in Washington, D.C., and a visiting professor in Intcrnatiorr;il Studies at Ihke University. A longer version 01 this essay will apprai- ill W‘utching Tclcl;ision edited by Todd Citlin (Pantheon,January 1!987). -

Grant Singer on Making Music Videos

April 3, 2017 - Grant Singer is a filmmaker and music video director based in Los Angeles. Over the past five years he's worked with Lorde, Ariel Pink, Sky Ferreira, Taylor Swift, and the Weeknd, among others. As told to T. Cole Rachel, 1703 words. Tags: Film, Music, Inspiration, Process, Beginnings. Grant Singer on making music videos In the last couple of years you’ve directed videos for Taylor Swift, The Weeknd, Ariana Grande, and Lorde. Are you someone who grew up watching a lot of music videos? My first memories as a human being are specifically watching music videos in my parents’ garage. I remember the Warrant “Cherry Pie” video stuck out to me when I was four of five years old, and then Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun” video and Soul Asylum’s “Runaway Train” video. When I was a little bit older I was introduced to Mark Romanek’s Nine Inch Nails videos as well as Chris Cunningham’s work. Music videos, for sure, influenced me when I was younger, but I never thought I’d grow up and direct music videos. If I had seen a psychic years ago who said, “In 10 years you’ll be directing music videos,” I wouldn’t have believed her. It was never an aspiration that I had. When I went to college, my first year, I studied music and I wanted to compose music for film. It wasn’t until a little later that I realized I wanted to direct the films, not just do the music. From that point on, my focus was directing, but I never thought I’d direct music videos until I was in my 20s. -

Simon and Garfunkel the Concert in Central Park

You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING Simon and The concert Simon and The concert Simon and The concert Garfunkel in Central Park Garfunkel in Central Park Garfunkel in Central Park 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 Humph Hall Humph Hall Humph Hall 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Scarborough Fair, Wake Up Little Suzie, Still Crazy After All These Scarborough Fair, Wake Up Little Suzie, Still Crazy After All These Scarborough Fair, -

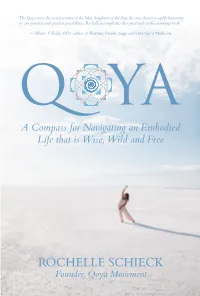

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

Cinebox E Scopitone

Immagini d’epoca di Cinebox e Scopitone. 96 VERDI VIVA tv&musica CINEBOX GLI ANTENATI DEL VIDEOCLIP di Michele Bovi Il videoclip non è nato a New York, Anno 1959: nascita e ascesa di un genere che è insieme televisione e musica. né a Hollywood. È nato a Cologno Monzese, a Non a New York ma a Cologno Monzese. È il “fonografo visivo” o, più semplicemente, Nord di Milano, nel gennaio del 1959. Gli studi il juke-box “ per immagini” che in America aveva avuto vita breve negli anni ’40 di realizzazione erano quelli di Cinelandia, il regista Enzo Trapani (pietra miliare dell’intrat- con filmati in bianco&nero di jazzisti del calibro di Amstrong e Eckstein. tenimento televisivo della prima Rai), i produt- E nel 1981, con l’esordio di Mtv, irrompe la definizione attuale tori due fratelli milanesi: Angelo e Giovanni Bottani. La prima pellicola musicale a colori, girata in 16 millimetri, ebbe come protagonisti da 100 lire: una moneta per un filmato (mentre Peppino Di Capri e i suoi Rockers: il brano s’in- l’ormai affermato cugino juke box con 100 lire titolava Come è bello, una marcetta composta da consentiva l’ascolto di tre canzoni). Alla Fiera di Renato Rascel, durata tre minuti scarsi. Milano i fratelli Bottani illustrarono l’operazio- L’azienda degli intraprendenti Bottani Brothers ne: in fabbrica erano pronti 500 apparecchi da si chiamava Sif (Società Internazionale di collocare nei migliori esercizi della penisola, Fonovisione, sita in Corso Matteotti al numero con l’impegno di distribuirne 4.000 in due 8 a Milano) e nei successivi 60 giorni realizzò anni al ritmo di 500 per trimestre.