Franz Kafka the CASTLE IT Was Late in the Evening When K. Arrived, The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Literary Tradition in Roth's Kepesh Trilogy

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 2 Article 8 European Literary Tradition in Roth's Kepesh Trilogy Gustavo Sánchez-Canales Autónoma University Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Sánchez-Canales, Gustavo. -

Early Dutch Settlements in South Dakota

EARLY DUTCH SETTLEMENTS IN SOUTH DAKOTA The first families came to this area from the Netherlands because economic conditions were such that there was no future for farmers and artisans. Wages were very low, both for the laboring class and the farmer. Many farmers had retrogressed to such an extent that they were forced to abandon their farms, and many workmen were unable to find employment. I recall that many carpenters complained about conditions, and they did not believe that it would be much better in the United States. Moreover, there were very few who had the means to pay for such a journey. Only those who had received some money from an inheritance began to think about emigrating. Rickele Zylstra, son of Je1le Zylstra, made plans to go to America with his family. I believe that he left during the latter part of 1881, and his brother Rein went with him, as well as a few families from Wolvega. The latter had acquaintances in BonHomme County, and all first went to that area. In 1882 these two sons of uncle Je1le went to Charles Mix County, and took up a claim. Riekele built a sod house for his family, but Rein returned to the Netherlands to be married. But alas, the girl of his choice refused to go to America, so Rein returned alone. In 1883 Douse, the third son of uncle Jelle, came here, and with him a family from the province of Groningan, namely 1. Dyksterhuis, with his wife, son, and two daughters. An older son had arrived a year earlier. -

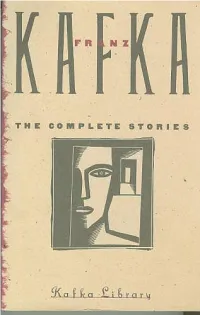

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

Linkin Park Videos for Download

Linkin park videos for download Numb/Encore [Live] (Clean Version) Linkin Park & Jay Z. Linkin Park - One Step Closer (Official Video) One Step Closer (Official Video) Linkin Park. Linkin Park. Tags: Linkin Park Video Songs, Linkin Park HD Mp4 Videos Download, Linkin Park Music Video Songs, Download 3gp Mp4 Linkin Park Videos, Linkin Park. Linkin Park - Numb Lyrics [HQ] [HD] Linkin Park - Numb (R.I.P Chester Bennington) HORVÁTH TAMÁS - Chester Bennington (Linkin Park) - Numb (Sztárban Sztár ). Linkin Park Heavy Video Download 3GP, MP4, HD MP4, And Watch Linkin Park Heavy Video. Watch videos & listen free to Linkin Park: In the End, Numb & more. Linkin Park is an American band from Agoura Hills, California. Formed in the band rose. This page have Linkin Park Full HD Music Videos. You can download Linkin Park p & p High Definition Blu-ray Quality Music Videos to your computer. Let's take a look back at Linkin Park's finest works as we count down their 10 Best Songs. Watch One More Light by Linkin Park online at Discover the latest music videos by Linkin Park on. hd video download, downloadable videos download music, music Numb - Linkin Park Official Video. Kiiara). Directed by Tim Mattia. Linkin Park's new album 'One More Light'. Available now: Linkin Park - Live At Download Festival In Paris, France Full Concert HD p. Video author: https. Linkin Park "Numb" off of the album METEORA. Directed by Joe Hahn. | http. Linkin Park "CASTLE OF GLASS" off of the album LIVING THINGS. "CASTLE OF I'll be spending all day. Videos. -

Getting to the Point. Index Sets and Parallelism-Preserving Autodiff for Pointful Array Programming

Getting to the Point. Index Sets and Parallelism-Preserving Autodiff for Pointful Array Programming ADAM PASZKE, Google Research, Poland DANIEL JOHNSON, Google Research, Canada DAVID DUVENAUD, University of Toronto, Canada DIMITRIOS VYTINIOTIS, DeepMind, United Kingdom ALEXEY RADUL, Google Research, USA MATTHEW JOHNSON, Google Research, USA JONATHAN RAGAN-KELLEY, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA DOUGAL MACLAURIN, Google Research, USA We present a novel programming language design that attempts to combine the clarity and safety of high-level functional languages with the efficiency and parallelism of low-level numerical languages. We treat arraysas eagerly-memoized functions on typed index sets, allowing abstract function manipulations, such as currying, to work on arrays. In contrast to composing primitive bulk-array operations, we argue for an explicit nested indexing style that mirrors application of functions to arguments. We also introduce a fine-grained typed effects system which affords concise and automatically-parallelized in-place updates. Specifically, an associative accumulation effect allows reverse-mode automatic differentiation of in-place updates in a way that preserves parallelism. Empirically, we benchmark against the Futhark array programming language, and demonstrate that aggressive inlining and type-driven compilation allows array programs to be written in an expressive, “pointful” style with little performance penalty. CCS Concepts: • Software and its engineering ! Functional languages; Parallel programming lan- guages; • Mathematics of computing ! Automatic differentiation. Additional Key Words and Phrases: array programming, automatic differentiation, parallel acceleration 1 INTRODUCTION Recent years have seen a dramatic rise in the popularity of the array programming model. The model was introduced in APL [Iverson 1962], widely popularized by MATLAB, and eventually made its way into Python. -

Rewind, Play, Fast Forward : the Past, Present and Future of the Music Video, Bielefeld 2010, S

Originalveröffentlichung in: Keazor, Henry ; Wübbena, Thorsten (Hrsgg.): Rewind, play, fast forward : the past, present and future of the music video, Bielefeld 2010, S. 7-31 Rewind - Play - Fast Forward The Past, Present and Future of the Music Video: Introduction HENRY KEAZOR/THORSTEN WUBBENA "Art presses the "Stop"- and "Rewind"- buttons in the stream of life: It makes time stop. It offers reflection and re collection, it is an antidote against lost certitudes."1 Like perhaps no other medium, the music video clip is marking and shap ing our everyday culture: film, art, literature, advertisements they all are clearly under the impact of the music video in their aesthetics, their technical procedures, visual worlds or narrative strategies. The reason for this has not only to be sought in the fact that some of the video di rectors are now venturing into art or advertisement, but that also peo ple not working in the field of producing video clips are indebted to this medium.2 Thus, more or less former video clipdirectors such as Chris Cunningham or Jonas Akerlund have established themselves successfully with their creations which very often are based on ideas and concepts, originally developed for earlier music videos: both Cunningham's works Flex and Monkey Drummer, commissioned in 2000 respectively 2001 by the Anthony d'Offay Gallery, evolved out of his earlier music videos.' Flex relies on the fantastic and weightless underwater cosmos Cunningham designed for the images that accompanied Portishead's Only you in 1998. Monkey Drummer* is heavily based on the soundtrack written by the Irish musician Aphex Twin (Richard David James) for whom Cunningham had previously directed famous videos such as Come to Daddy (1997) and Win- dowlicker (1999). -

This Digital Proof Is Provided for Free by UDP. It Documents the Existence

This digital proof is provided for free by UDP. It documents the existence of the book Residual Synonyms For The Name of God by Lewis Freedman, which was published in 2016 in an edition of 1000. If you like what you see in this proof, we encourage you to purchase the book directly from UDP, or from our distributors and partner bookstores, or from any independent bookseller. If you find our Digital Proofs program useful for your research or as a resource for teaching, please consider making a donation to UDP. If you make copies of this proof for your students or any other reason, we ask you to include this page. Please support nonprofit & independent publishing by making donations to the presses that serve you and by purchasing books through ethical channels. UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE uglyducklingpresse.org … UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE Residual Synonyms For The Name of God by Lewis Freedman (2016) - Digital Proof RESIDUAL SYNONYMS FOR THE NAME OF GOD Residual Synonyms for the Name of God Copyright 2016 by Lewis Freedman First Edition, First Printing Ugly Duckling Presse 232 Third Street, #E303 Lewis Freedman Brooklyn, NY 11215 uglyducklingpresse.org Distributed in the USA by SPD/Small Press Distribution 1341 Seventh Street Berkeley, CA 94710 spdbooks.org ISBN 978-1-937027-65-0 Design by Doormouse Typeset in Baskerville Cover printed letterpress at UDP Printed and bound at McNaughton & Gunn Edition of 1000 Support for this publication was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts Ugly Duckling Presse Brooklyn, NY UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE Residual Synonyms For The Name of God by Lewis Freedman (2016) - Digital Proof PREFACE and attributes of assisting vitalities. -

Poems Written by Students of St Genevieve's High School, Belfast During A

Poems written by students of St Genevieve’s High School, Belfast during a residency with poet, Kate Newmann. Supported by the Department of Foreign Affair and Trade. Tierna Crossan MYSTERY Yesterday I was doing homeworK in my room, and the window was closed. I was sitting with my little sister and I smelt my granny’s perfume. I looKed, and I was confused. I said to her Nicole, did you spray perfume? She said, No. Because she was colouring in, I acted as if it was nothing, but I smelt it again – as if someone was spraying it in front of me, but no one was there. I listen, and process every word. Silence chooses me. The apparition is a butterfly showing itself to me. The difference between bone and breath is solid and air. MY GRANDA He is a ten pound note that is hidden behind the lyrics of a song. He is a crossword puzzle book that fills in all the blanKs for you. He is a downfall of rain, followed by sunshine. He is a rich seafood chowder bubbling in a pot. He is a raging flame that wouldn’t go out. He is his own song that he had written for himself. LANZAROTE The words sink deep under the water. The blazing sun glaring down at me is beyond my reach. The heartbeat speeds up with all the excitement. My pocket’s distended because of al the seashells I collected. I grow tired of the heat pounding down on me. The longest voice is the man in the restaurant telling the specials. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. OXFORD WORLD'S CLASSICS OXFORD WORLD'S CLASSICS For over 100 years Oxford World'J Classics have brought readers closer to the morld's great litera·ture. Nom mith over 700 titles-from the 4,ooo-year-old myths ofMesopotamia to the FRANZ KAFKA twentieth century's greatest IW1'els-the series makes available lesser-known as me" as celebrated mriting. The pocket-sized hardbacks ofthe early years contained A Hunger Artist ill/roductiolls by Virginill Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, alld other literalJlfigures mhich eIlriched the experience ofreading. and Other Stories Today the set'ies is recogllizedfor ilsfine scholarship and reliability ill texts that span world liurature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy, lind politics. Each edition includes perceptive commel/t.ary and essential background information to meet the changing needs ofreaders. Translated by JOYCE CRICK With an Introduction and Notes by RITCHIE ROBERTSON OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 56 A Hunger Artist: Four Stories A Hunger Artist 57 the wider world would be concerned with the affair after all-where, the personal direction of the performer himself, nowadays it is as I shall keep repeating, it has no jurisdiction-I shall not, I admit, completely impossible. -

The Castle and the Village: the Many Faces of Limited Access

01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 3 1 The Castle and the Village: The Many Faces of Limited Access jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi Access Denied No author in world literature has done more to give shape to the nightmarish challenges posed to access by modern bureaucracies than Franz Kafka. In his novel The Castle, “K.,” a land surveyor, arrives in a village ruled by a castle on a hill (see Kafka 1998). He is under the impression that he is to report for duty to a castle authority. As a result of a bureaucratic mix-up in communications between the cas- tle officials and the villagers, K. is stuck in the village at the foot of the hill and fails to gain access to the authorities. The villagers, who hold the castle officials in high regard, elaborately justify the rules and procedures to K. The more K. learns about the castle, its officials, and the way they relate to the village and its inhabitants, the less he understands his own position. The Byzantine codes and formalities gov- erning the exchanges between castle and village seem to have only one purpose: to exclude K. from the castle. Not only is there no way for him to reach the castle, but there is also no way for him to leave the village. The villagers tolerate him, but his tireless struggle to clarify his place there only emphasizes his quasi-legal status. Given K.’s belief that he had been summoned for an assignment by the authorities, he remains convinced that he has not only a right but also a duty to go to the cas- tle! How can a bureaucracy operate in direct opposition to its own stated pur- poses? How can a rule-driven institution be so unaccountable? And how can the “obedient subordinates” in the village wield so much power to act in their own self- 3 01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 4 4 jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi interest? But because everyone seems to find the castle bureaucracy flawless, it is K. -

1 Franz Kafka (1883-1924) the Metamorphosis (1915)

1 Franz Kafka (1883-1924) The Metamorphosis (1915) Translated by Ian Johnston, Malaspina University-College I One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that, in his bed, he had been changed into a monstrous vermin. He lay on his armour-hard back and saw, as he lifted his head up a little, his brown, arched abdomen divided up into rigid bow-like sections. From this height the blanket, just about ready to slide off completely, could hardly stay in place. His numerous legs, pitifully thin in comparison to the rest of his circumference, flickered helplessly before his eyes. “What’s happened to me,” he thought. It was no dream. His room, a proper room for a human being, only somewhat too small, lay quietly between the four well-known walls. Above the table, on which an unpacked collection of sample cloth goods was spread out—Samsa was a travelling salesman—hung the picture which he had cut out of an illustrated magazine a little while ago and set in a pretty gilt frame. It was a picture of a woman with a fur hat and a fur boa. She sat erect there, lifting up in the direction of the viewer a solid fur muff into which her entire forearm had disappeared. Gregor’s glance then turned to the window. The dreary weather—the rain drops were falling audibly down on the metal window ledge—made him quite melancholy. “Why don’t I keep sleeping for a little while longer and forget all this foolishness,” he thought. -

Simon and Garfunkel the Concert in Central Park

You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING You are invited to a FREE FILM SCREENING Simon and The concert Simon and The concert Simon and The concert Garfunkel in Central Park Garfunkel in Central Park Garfunkel in Central Park 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 7pm, Thursday 13th Oct 2011 Humph Hall Humph Hall Humph Hall 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights 85 Allambie Road, Allambie Heights Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon Enjoy the Central Park reunion with half a million fans as Simon and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. and Garfunkel perform together for the first time in 11 years. Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance Filmed on September 19, 1981, the beautiful performance bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] bespeaks the emotional intensity of the occasion. [87m] Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Songs include: Mrs Robinson, Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard, Scarborough Fair, Wake Up Little Suzie, Still Crazy After All These Scarborough Fair, Wake Up Little Suzie, Still Crazy After All These Scarborough Fair,