Interpretierte Eisenzeiten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aktionsplan Teil 3

Bundesland Kärnten Auswertung der Strategischen Lärmkarten (nach K-ULV) Auswertung von Landesstraßen (B+L) und Gemeindestraßen mit mahr als 3 Mio. Kfz/Jahr nach den Anforderungen der Kärntner-Umgebungslärmverordnung (K-ULV) Anzahl der Hauptwohnsitze nach Pegelzonen Lden Lnight ≥ 55 ≥ 60 ≥ 65 ≥ 70 ≥ 50 ≥ 55 ≥ 60 ≥ 65 S S < 60 < 65 < 70 < 75 ≥ 75 < 55 < 60 < 65 < 70 ≥ 70 Velden am Wörther See 3.247 813 960 1.474 0 0 2.595 1.000 1.595 0 0 0 Hermagor-Pressegger See 236 154 45 33 4 0 97 59 27 11 0 0 Steindorf am Ossiacher See 233 80 96 57 0 0 174 107 65 2 0 0 Lendorf 317 154 33 130 0 0 163 33 57 73 0 0 Lurnfeld 83 83 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Völkermarkt 467 236 111 103 17 0 245 100 128 17 0 0 Eberndorf 77 41 29 7 0 0 36 29 7 0 0 0 Villach 21.895 8.286 6.693 5.083 1.809 24 17.555 7.892 5.471 3.818 367 7 Wolfsberg 1.064 713 214 116 21 0 402 243 113 46 0 0 Sankt Andrä 281 180 73 28 0 0 123 95 28 0 0 0 Millstatt 162 56 50 43 13 0 106 53 36 17 0 0 Seeboden 735 417 154 100 64 0 327 163 97 67 0 0 Spittal an der Drau 2.122 762 368 785 207 0 1.397 405 756 236 0 0 Wernberg 338 150 124 64 0 0 211 113 97 1 0 0 Finkenstein 133 80 26 27 0 0 66 39 27 0 0 0 Arnoldstein 81 34 29 18 0 0 54 36 18 0 0 0 Treffen am Ossiachersee 335 160 132 37 6 0 171 126 39 6 0 0 Paternion 114 54 47 13 0 0 66 51 15 0 0 0 Weißenstein 255 149 94 12 0 0 114 94 20 0 0 0 Ebenthal in Kärnten 343 168 123 52 0 0 178 119 54 5 0 0 Grafenstein 24 12 12 0 0 0 12 12 0 0 0 0 Poggersdorf 26 13 13 0 0 0 14 14 0 0 0 0 Magdalensberg 86 0 86 0 0 0 86 0 86 0 0 0 Ferlach 107 60 25 22 0 0 53 19 34 0 0 0 -

Landtagswahl 2018 – Kreiswahlvorschläge Wahlkreis 1 KUNDMACHUNG Gemäß § 47 Der Landtagswahlordnung 1974, Lgbl

Landtagswahl 2018 – Kreiswahlvorschläge Wahlkreis 1 KUNDMACHUNG Gemäß § 47 der Landtagswahlordnung 1974, LGBl. Nr. 191, zuletzt geändert durch LGBl. 25/2017, werden nachstehend die Kreiswahlvorschläge des Wahlkreises 1 für die Landtagswahl am 4. März 2018 veröffentlicht. Liste 1 Liste 2 Liste 3 Liste 4 Liste 5 Liste 6 Liste 7 Liste 8 Liste 9 Liste 10 Peter Kaiser – Die Grünen – Bündnis Liste Verantwortung Neos und Kommunistische Die Freiheitlichen Kärntner Team Kärnten – Liste Fair – Sozialdemokratische Die Grüne Alternative Zukunft Kärnten Neu Erde – Global Denken, Mein Südkärnten Partei Österreichs und in Kärnten Volkspartei Liste Köfer Dr. Marion Mitsche Partei Österreichs Kärnten – Rolf Holub – Liste Helmut Nikel Lokal Handeln Moja Južna Koroška Unabhängige Linke/Levica SPÖ FPÖ ÖVP GRÜNE TK BZÖ ERDE NEOS FAIR KPÖ 1. Mag. Dr. Kaiser Peter, 1958, 1. Mag. Darmann Gernot, 1975, Jurist, 1. Gaggl Herbert, 1955, Geschäftsführer, 1. DI Johann Michael, 1963, Forstwirt, 1. Jandl Klaus-Jürgen, 1965, Gemein- 1. Nikel Helmut, 1966, Angestellter, 1. Wallenböck Victoria, 1989, Rechts- 1. Mag. Unterdorfer-Morgenstern 1. Dr. Mitsche Marion, 1978, Psychologin, 1. Mag. Dr. Pirker Bettina, 1971, Medien- Landeshauptmann, 9020 Klagenfurt 9073 Klagenfurt-Viktring 9062 Moosburg 9173 St. Margareten derat, 9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee 9131 Grafenstein kanzleiassistentin, 9020 Klagenfurt Markus, 1972, Jurist, Unternehmer, 9620 Hermagor wissenschaftlerin, 9020 Klagenfurt am am Wörthersee am Wörthersee 9871 Seeboden Wörthersee 2. Mag. LL.M. Leyroutz Christian, 1970, 2. Hairitsch Petra, 1964, Hortpädagogin, 2. Mag. Motschiunig Margit, 1964, Päda- 2. Mag. BEd. Feodorow Johann, 1985, 2. Lassnig Jürgen, 1967, Vertragsbedien- 2. Gasper Reinhold, 1938, Pensionist, 2. Dr. Schaunig-Kandut Gabriele, 1965, Rechtsanwalt, 9020 Klagenfurt am 9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee gogin, 9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee Pädagoge, 9020 Klagenfurt steter, 9131 Grafenstein 2. -

62 62 Rund Um Den **Magdalensberg CO **Hochosterwitz CP **Maria Saal CN

Tour 4 Schatzkammer der Geschichte Klagenfurt ➜ **Maria Saal ➜ *St. Veit ➜ Gurk ➜ *Friesach Tour 4 Historisches Gelände umfängt der Blick über das Zollfeld ost- und süd- ostwärts. Dort dehnte sich einst die Römerstadt Virunum aus. Archäolo- gen legten Straßenzüge frei und re- konstruierten den Stadtplan, doch dann wurde die Stätte aus Geldman- gel wieder zugeschüttet – und somit bestens konserviert. Kollerwirt, Affelsdorf 3, Tel. Der Herzogstuhl, Kärntens altes 0 42 23/26 03. Vielfach ausge- Herrschaftszeichen zeichnetes Gasthaus mit feiner Kärnt- Nichts für schwache Nerven: ner Küche und guter Weinauswahl der Karner von Maria Saal Grab- und Reliefplatten aus Römerzeit (hinter dem Konvikt Tanzenberg). ❍❍ und Mittelalter eingemauert. Hochosterwitz, eine der schönsten Pfarrkirche St. Peter und Paul steht Der barocke Hochaltar, die zwei go- Burgen Österreichs fest, beinahe trotzig, in einem kleinen tischen Flügelaltäre und die Gewölbe- Rund um den 6 4 Friedhof. Sie ist eine der beliebtesten ausmalung des Mittelschiffs (15. Jh.) **Magdalensberg CO Vom Ruinenfeld führt die Straße 4 Hochzeitskirchen Kärntens. sind Blickfang einer verschwenderi- bergauf zu einem weiteren Glanzlicht, Karte Karte Seite Ein besonderer Ort ist auch der schen Innenausstattung. Eindrucksvolle Ruinen kann man auf dem Gipfel des Magdalensbergs Seite 62 steile Ulrichsberg dahinter. Er war ein Etwas außerhalb des Ortskerns dem Magdalensberg (22 km) besich- (1058 m) mit einem grandiosen Blick 62 heiliger Berg der frühen Kärntner. Ein bummelt man im Kärntner Freilicht- tigen. Rund 2,5 km2 umfasste die ins Kärntner Land. Das spätgotische keltisch-römisches Heiligtum der Isis museum durch eine bäuerliche Welt spätkeltisch-frührömische, terrassier- Wallfahrtskirchlein St. Helena und Noreia und eine Doppeltempelanlage vergangener Tage. Das Ensemble, te Stadt, ein Zentrum des Handels im Magdalena erhebt sich über den Re- mit kultischem Bassin sind in Resten 36 Häuser und Höfe aus allen Regio- Ostalpenraum. -

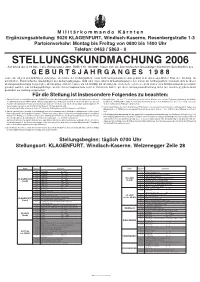

Kärnten 2006.Pmd

M i l i t ä r k o m m a n d o K ä r n t e n Ergänzungsabteilung: 9020 KLAGENFURT, Windisch-Kaserne, Rosenbergstraße 1-3 Parteienverkehr: Montag bis Freitag von 0800 bis 1400 Uhr Telefon: 0463 / 5863 - 0 STELLUNGSKUNDMACHUNG 2006 Auf Grund des § 18 Abs. 1 des Wehrgesetzes 2001, BGBl. I Nr. 146/2001, haben sich alle österreichischen Staatsbürger männlichen Geschlechtes des G E B U R T S J A H R G A N G E S 1 9 8 8 sowie alle älteren wehrpflichtigen Jahrgänge, die bisher der Stellungspflicht noch nicht nachgekommen sind, gemäß dem unten angeführten Plan der Stellung zu unterziehen. Österreichische Staatsbürger des Geburtsjahrganges 1988 oder eines älteren Geburtsjahrganges, bei denen die Stellungspflicht erst nach dem in dieser Stellungskundmachung festgelegten Stellungstag entsteht, haben am 14.12.2006 zur Stellung zu erscheinen, sofern sie nicht vorher vom Militärkommando persönlich geladen wurden. Für Stellungspflichtige, welche ihren Hauptwohnsitz nicht in Österreich haben, gilt diese Stellungskundmachung nicht. Sie werden gegebenenfalls gesondert zur Stellung aufgefordert. Für die Stellung ist insbesondere Folgendes zu beachten: 1. Für den Bereich des Militärkommandos KÄRNTEN werden die Stellungspflichtigen durch die Stellungskommission 4. Wehrpflichtige, die das 17. Lebensjahr vollendet haben, können sich bei der Ergänzungsabteilung des Militär- des Militärkommandos KÄRNTEN der Stellung zugeführt. Das Stellungsverfahren, bei welchem durch den Einsatz kommandos KÄRNTEN freiwillig zur vorzeitigen Stellung melden. Sofern militärische Interessen nicht entgegen- moderner medizinischer Geräte und durch psychologische Tests die körperliche und geistige Eignung zum Wehr- stehen, wird solchen Anträgen entsprochen. dienst genau festgestellt wird, nimmt in der Regel 1 1/2 Tage in Anspruch. -

Rauchfangkehrer-Änderung.Pdf

Zugestellt durch Post.at GEMEINDE MARIA WÖRTH Wörthersee Süduferstraße – Am Corso 115, 9081 Reifnitz Tel. 04273-2050-0, Fax: 04273-2050-42, E-Mail: [email protected] www.maria-woerth.info Sehr geehrte Gemeindebürgerinnen und Gemeindebürger! Gerade jetzt in der laufenden Heizsaison dient die Tätigkeit der öffentlich zugelassenen Rauchfangkehrer bei der Durchführung von sicherheitsrelevanten Aufgaben wesentlich öffentlichen Interessen, insbesondere dem Schutz der Gesundheit und von Leib und Leben. Betroffen von einer allfälligen Gefährdung sind nicht nur die Benutzer eines Gebäudes, sondern auch die Benutzer der Nachbarobjekte sowie die bei einem allfälligen Brand befassten Einsatzkräfte. Die Kärntner Gefahren- und Feuerpolizeiordnung verpflichtet Gebäudeeigentümer, Nutzungsberechtigte und Hausverwaltungen (wenn solche bestellt sind), die Überprüfungstätigkeiten und die Kehrungen von Rauchfängen (Abgasanlagen) sowie der Verbindungsstücke einem Rauchfangkehrer zu übertragen. Diese beschriebenen Arbeiten sind von einem Rauchfangkehrer, dessen Gewerbeberechtigung die Besorgung sicherheitsrelevanter Tätigkeiten im Sinne der Gewerbeordnung mitumfasst („öffentlich zugelassener Rauchfangkehrer“), durchzuführen. Im Kehrgebiet II der Kehrgebietsverordnung haben folgende zwei Rauchfangkehrer-Meisterbetriebe ihre Gewerbeausübung eingestellt: - Gebhart Hiebler, Seigbichler Straße 2, 9062 Moosburg und - Josef Tautscher, Dobrovagasse 6, 9170 Ferlach Sollte Ihr kehr- bzw. überprüfungspflichtiges Gebäude infolge der Einstellung der Gewerbeausübung -

Wasser Für Kärnten „Empfehlungen Für Eine Nachhaltige Trinkwasserversorgung“ (Trinkwasserversorgungskonzept Kärnten 2005)

Wasser für Kärnten „Empfehlungen für eine nachhaltige Trinkwasserversorgung“ (Trinkwasserversorgungskonzept Kärnten 2005) Hochbehälter Wolschartwald Tiebelquellen der Brunnenanlage St. Klementen (Krappfeld) Förolacherstollen Brunnen Traundorf Amt der Kärntner Landesregierung Abteilung 18 - Wasserwirtschaft Dezember 2005 Vorwort 1984 wurde Kärnten zum Vorreiter unter Österreichs Bundesländern mit einem ersten landesweiten Wasserversorgungskonzept. Damals wurde eine umfangreiche Erhebung der Dargebote und des Bedarfs durchgeführt und ein Verteilungsmodell für die Versorgung von 9 Wassermangelgebieten aus 8 Großspendern erstellt. Aber bereits in den 1970 er Jahren wurden Studien über die Wasserversorgung des Mittelkärntner Raumes durchgeführt, da sich der Kärntner Zentralraum damals wie heute als Zuzugsraum entwickelte. Im Kärntner Regierungsprogramm 2004-2009 wurde eine flächendeckende Wasserbedarfserhebung angekündigt um ein klares Bild und genaue Daten über die tatsächlichen Bedarfspotentiale in allen Teilen unseres Bundeslandes zu erhalten. Weiters: „Die Vernetzung bestehender Wasserversorgungsanlagen und der Ausbau der "Kärntner Wasserschiene" sind vorrangige Ziele. Wichtige, überregional bedeutende Wasservorkommen sind vom Land Kärnten in geeigneter Form für die Kärntner Bevölkerung zu sichern, um sie jedweden Spekulationen zu entziehen, damit wir diese im Bedarfsfall zur Nutzung für unterversorgte Gebiete unseres Landes zur Verfügung haben. Der gesamten Kärntner Bevölkerung muss Wasser in ausreichender Menge und zu sozial verträglichen -

Kärntner Ortsverzeichnis

KÄRNTNER ORTSVERZEICHNIS Gebietsstand 1.1.2014 AMT DER KÄRNTNER LANDESREGIERUNG L a n d e s s t e l l e f ü r S t a t i s t i k KÄRNTNER ORTSVERZEICHNIS Gebietsstand 1. 1. 2014 Auszugsweiser Abdruck nur mit Quellenangabe gestattet Herausgegeben: AMT DER KÄRNTNER LANDESREGIERUNG Landesstelle für Statistik Zusammenstellung: Winfried VALENTIN EDV-technische Durchführung: Winfried VALENTIN Wolfgang WEGHOFER Titelgraphik: DI Wilfried KOFLER Redaktion und für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Dr. Peter IBOUNIG V O R W O R T 2.823 Ortschaften gibt es insgesamt in unseren 132 Gemeinden. Das vorliegende „Kärntner Ortsverzeichnis“ bildet nicht nur diese Vielfalt und Vielseitigkeit ab, sondern schafft auch zahlreiche Orientierungspunkte. Der Band kann Politik und Verwaltung als Planungsgrundlage dienen und stellt darüber hinaus ein nützliches Nachschlagewerk für Bürgerinnen und Bürger dar. Das Ortsverzeichnis hat eine bereits vier Jahrzehnte lange Tradition. Man startete damit 1973, als das Land Kärnten mittels Gemeindestrukturreform die kommunale Landschaft wesentlich verbessert und die Zahl der ehemals 203 Gemeinden nahezu halbiert hatte. Seither wird es von der Landesstelle für Statistik in gewissen Zeitabständen neu aufgelegt. Die aktuelle Publikation ist bereits die zehnte dieser Reihe. Nachlesen kann man in ihr auch die aus der Registerzählung 2011 zur Verfügung stehenden Eckdaten für die einzelnen Ortschaften. Natürlich werden gemäß der jüngsten Änderung des Volksgruppengesetzes vom 26. Juli 2011 die entsprechenden Ortschaften im gemischtsprachigen Gebiet Kärntens sowohl in deutscher als auch in slowenischer Sprache ausgewiesen. An dieser Stelle möchte ich aber auch betonen, dass wir seitens der Kärntner Landesregierung die Entwicklung der Regionen, insbesondere des ländlichen Raumes, fördern und unterstützen wollen. -

Arbeitsstätten Und Beschäftigte Nach Gemeinden

Arbeitsstätten1) und Beschäftigte nach Gemeinden Mini-Registerzählung 2017 Arbeits- davon mit … unselbständig Beschäftigten Be- Politischer Bezirk stätten schäftigte ins- Gemeinde ins- 100 0 1-4 5-9 10-49 50-99 2) gesamt u.mehr gesamt Kärnten 41.581 18.793 14.543 4.028 3.562 396 259 245.530 Klagenfurt Stadt 9.497 4.064 3.375 967 877 109 105 72.502 Villach Stadt 4.808 1.932 1.779 515 470 64 48 37.042 Feldkirchen 2.186 1.023 744 222 172 16 9 10.248 Albeck 60 28 19 12 1 - - 171 Feldkirchen in Kärnten 1.102 439 390 140 114 15 4 6.480 Glanegg 99 49 32 8 7 1 2 650 Gnesau 50 23 15 7 4 - 1 367 Himmelberg 149 77 54 11 7 - - 397 Ossiach 74 35 30 4 5 - - 229 Reichenau 121 50 47 13 10 - 1 542 St.Urban 101 54 31 9 7 - - 322 Steindorf am Ossiacher See 268 141 98 13 15 - 1 813 Steuerberg 162 127 28 5 2 - - 277 Hermagor 1.352 558 538 130 114 8 4 6.357 Dellach 64 32 19 7 6 - - 249 Gitschtal 80 36 27 11 6 - - 311 Hermagor-Pressegger See 613 213 274 58 60 7 1 3.259 Kirchbach 130 65 43 11 11 - - 486 Kötschach-Mauthen 302 125 117 32 25 - 3 1.574 Lesachtal 106 56 37 8 4 1 - 309 St. Stefan im Gailtal 57 31 21 3 2 - - 169 Klagenfurt Land 4.006 2.181 1.271 291 230 24 9 14.923 Ebenthal in Kärnten 401 224 117 29 30 1 - 1.329 Feistritz im Rosental 141 62 43 15 20 1 - 784 Ferlach 480 209 179 51 34 5 2 2.894 Grafenstein 198 101 55 20 21 1 - 808 Keutschach am See 188 121 51 7 9 - - 440 Köttmannsdorf 171 101 47 15 8 - - 429 Krumpendorf am Wörthersee 360 203 117 23 13 2 2 1.272 Ludmannsdorf 86 53 23 7 2 1 - 288 Magdalensberg 201 105 63 15 16 2 - 748 Maria Rain 167 112 44 5 6 - - 361 Maria Saal 253 146 77 15 11 3 1 1.069 Maria Wörth 162 87 55 12 5 3 - 579 Moosburg 280 151 89 24 13 2 1 1.061 Poggersdorf 196 100 63 19 13 1 - 746 Pörtschach am Wörther See 344 180 131 15 14 1 3 1.178 Schiefling am Wörthersee 168 99 55 6 8 - - 392 St. -

Brown Bear Remains in Prehistoric and Early Historic Societies: Case Studies from Austria 89-121 Berichte Der Geologischen Bundesanstalt 132

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt Jahr/Year: 2019 Band/Volume: 132 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kunst Günther Karl, Pacher Martina Artikel/Article: Brown bear remains in prehistoric and early historic societies: case studies from Austria 89-121 Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt 132 Brown bear remains in prehistoric and early historic societies: case studies from Austria Günther Karl Kunst 1 & Martina Pacher 2 Abstract Remains of brown bear (Ursus arctos LINNAEUS, 1758) are seldom recovered within archaeological assemblages. Nonetheless, interactions with bears and remains from this animal in past human so- cieties are diverse, as will be reflected in this paper through the discussion of a number of archaeo- zoological case studies from Austria. The aim of this study was to detect the varying roles of bears in pre- and early historic agricultural societies and to identify the importance of ‘rare’ elements. The study presents an investigation of the osteological indications of this particular species, within a de- fined area and across time. Bears did not supply an important contribution to daily consumption but this species was incorporated within varying contexts, suggesting a variety of different practices. Zusammenfassung Überreste von Braunbären (Ursus arctos LINNAEUS, 1758) werden in archäologischen Fundstellen selten geborgen. Interaktionen mit Bären und deren Überresten sind in früheren menschlichen Ge- sellschaften dennoch vielfältig, wie in diesem Artikel anhand einer Reihe von archäozoologischen Beispielen aus Österreich gezeigt wird. Ziel dieser Studie ist es, die unterschiedlichen Rollen von Bären in vor- und frühzeitlich historischen landwirtschaftlichen Gesellschaften zu erkennen und die Bedeutung von „seltenen“ Elementen zu identifizieren. -

Verteilung "Selbsttests" Für Betriebe

Dienststelle Adresse Zugeteilte Betriebe aus den Gemeinden Straßenbaumt Klagenfurt Josef Sablatnig Straße 245 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee 9020 Klagenfurt Krumpendorf am Wörthersee Maria Wörth Moosburg Poggersdorf Pörtschach am Wörther See Techelsberg am Wörther See Straßenmeisterei Rosental Klagenfurter Straße 41 Feistritz im Rosental 9170 Ferlach Ferlach Keutschach am See Köttmannsdorf Ludmannsdorf Maria Rain Rosegg Schiefling am Wörthersee St. Jakob im Rosental St. Margareten im Rosental Zell Straßenmeisterei Eberstein Klagenfurter Straße 7-9 Brückl 9372 Eberstein Eberstein Klein St. Paul Straßburg Weitensfeld im Gurktal Straßenmeisterei St. Ruprechter Straße 20 Albeck Feldkirchen 9560 Feldkirchen Feldkirchen in Kärnten Glanegg Gnesau Himmelberg Ossiach Reichenau St.Urban Steindorf am Ossiacher See Steuerberg Straßenmeisterei Friesach Industriestraße 44 Althofen 9360 Friesach Friesach Glödnitz Gurk Guttaring Hüttenberg Kappel am Krappfeld Metnitz Micheldorf Straßenmeisterei Klagenfurter Straße 51a Deutsch-Griffen St.Veit/Glan 9300 St.Veit/Glan Frauenstein Liebenfels Magdalensberg Maria Saal Mölbling St. Georgen am Längsee St.Veit an der Glan Straßenbauamt Villach Werthenaustraße 26 Arnoldstein 9500 Villach Arriach Feistritz an der Gail Finkenstein am Faaker See Hohenthurn Treffen am Ossiacher See Velden am Wörther See Villach Wernberg Straßenmeisterei Dueler Straße 88 Afritz am See Feistritz/Drau 9710 Feistritz/Drau Bad Bleiberg Feld am See Ferndorf Fresach Nötsch im Gailtal Paternion Stockenboi Weissenstein Straßenmeisterei Hermagor Egger -

Klagenfurt Klagenfurt Land

440000 442000 444000 446000 448000 450000 452000 14°12'0"E 14°13'0"E 14°14'0"E 14°15'0"E 14°16'0"E 14°17'0"E 14°18'0"E 14°19'0"E 14°20'0"E 14°21'0"E 14°22'0"E 14°23'0"E GL IDE number: N/A Activa tion ID: EMS R 340 ! ! Product N.: 12KL AGENFUR T AMW OR T HER S EE, v2, English ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ö 5 l 0 ! ! f n St.Ge orge n 0 ! ! itz ! ! 0 b Gotte sbichl ! ! 50 ac Klage nfurt am Wörthe rse - AUST RIA ! ! N h am Sand hof " ! ! 50 0 0 ' ! ! 9 ! ! 3 ! ° ! N 6 ! " ! Storm - Situation as of 01/01/2019 4 0 ! ! ' ! 9 ! 00 5 S POT 6 (01/01/2019 09:30 UT C) 3 ! ! ° ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! Magdalensberg Delinea tion Ma p ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Moosburg ! ! Obe roste rre ich ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 ! ! 0 0 0 ! ! 0 0 0 ! ! 0 0 ! ! 6 ! 6 ! ! 6 ! 500 6 ! 500 ! 1 ! 1 ! !! ! ! ! 5 ! 5 ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! 6 ! 00 ! Ste ie rm ark ! Salzburg ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Hohe nfe ld ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! Czech ! ! ! ! Nyugat-Dunantul ! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! ! Karnte n R epublic h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! T irol ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! c ! ! ! ! !! ! Kla genfurt a m Germa ny i ! ! ! 6 ! ! e ! 0 01 ! Görtschach W öerthersee ! t 02 Vienna ! ! 0 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 03 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! r ! ! ! ! (! ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 06 ! ! ! 08 ! ! ! 10 ! ! i 04 12 14 ! ! ! ! e ! ! ! R 05 ! !! ! ^ ! 16 ! n g 07 ! u 09 11 ! t 13 ! g e 15 Vzhod na ! r 5 e ! 0 ! i 0 Austria ! ! ! ! ! ! e ! ! ! ! 0 ! ! ! ! l h 0 ! 6 ! 00 l c s ! 5 ! i s Slove nija W a ! ! e ! 5 t ! ! ! ! ! ! H 0 T e ! ! 0 ! i ! c ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Zahod na ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! Sje ve rozapad na ! ! ! ! ! ! Ita ly ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Friuli-Ve ne zia ! ! S lovenia ! ! ! N ! " Slove nija ! 0 ' Hrvatsk aCroa tia 8 Giulia Adriatic 3 ° Sea N 6 " 4 0 ' ch 8 i 3 te ° Ve ne to l 6 erg 4 zb zberglteich u 1.Kreu 40 re Adriatic Sea K km 3. -

Kehrgebietsverordnung Rauchfangkehrerbetriebe

Sehr geehrte Gemeindebürgerinnen und Gemeindebürger! Gerade jetzt in der laufenden Heizsaison dient die Tätigkeit der öffentlich zugelassenen Rauchfangkehrer bei der Durchführung von sicherheitsrelevanten Aufgaben wesentlich öffentlichen Interessen, insbesondere dem Schutz der Gesundheit und von Leib und Leben. Betroffen von einer allfälligen Gefährdung sind nicht nur die Benutzer eines Gebäudes, sondern auch die Benutzer der Nachbarobjekte sowie die bei einem allfälligen Brand befassten Einsatzkräfte. Die Kärntner Gefahren- und Feuerpolizeiordnung verpflichtet Gebäudeeigentümer, Nutzungsberechtigte und Hausverwaltungen (wenn solche bestellt sind), die Überprüfungstätigkeiten und die Kehrungen von Rauchfängen (Abgasanlagen) sowie der Verbindungsstücke einem Rauchfangkehrer zu übertragen. Diese beschriebenen Arbeiten sind von einem Rauchfangkehrer, dessen Gewerbeberechtigung die Besorgung sicherheitsrelevanter Tätigkeiten im Sinne der Gewerbeordnung mitumfasst („öffentlich zugelassener Rauchfangkehrer“), durchzuführen. Im Kehrgebiet II der Kehrgebietsverordnung haben folgende zwei Rauchfangkehrer- Meisterbetriebe ihre Gewerbeausübung eingestellt: - Gebhart Hiebler, Seigbichler Straße 2, 9062 Moosburg und - Josef Tautscher, Dobrovagasse 6, 9170 Ferlach Sollte Ihr kehr- bzw. überprüfungspflichtiges Gebäude infolge der Einstellung der Gewerbeausübung seitens der beiden Rauchfangkehrerbetriebe nicht bereits von einem anderem Rauchfangkehrermeisterbetrieb betreut werden, empfehlen wir, so rasch als möglich einen Rauchfangkehrermeisterbetrieb