Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rare Bone Tumor

OPEN ACCESS L E T T E R T O T H E E D I T O R Periosteal Desmoplastic Fibroma of Radius: A Rare Bone Tumor Aniqua Saleem1,* Hira Saleem2 1 Radiology Department, District Head Quarters Hospital, Rawalpindi Medical University, Rawalpindi 2 Department of Surgery, Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad. Correspondence*: Dr. Aniqua Saleem, Radiology Department, District Head Quarters Hospital, Rawalpindi Medical University, Rawalpindi E-mail: [email protected] © 2019, Saleem et al, Submitted: 05-04-2019 Accepted: 09-06-2019 Conflict of Interest: None Source of Support: Nil This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. DEAR SIR Desmoplastic fibroma is an extremely rare tumor of enhancement on post contrast images and with adjacent bone with a reported incidence of 0.11 % of all primary bone involvement as was evident by focal cortical inter- bone tumors. The most common site of involvement is ruption, mild endosteal thickening and irregularity and mandible (reported incidence 22% of all Desmoplastic also mild ulnar shaft remodeling (Fig. 3a, 3b). To further fibroma cases) followed by metaphysis of long bones. characterize the lesion, Tc99 MDP (methylene diphos- Involvement of forearm especially involving periosteum phonate) bone scan was also performed which showed is seldom reported. Prompt diagnosis and adequate active bone involvement in left distal radial shaft. management is important for limb salvage and restora- tion of limb function. [1-3] An 11-year-old boy presented with painful mild swelling of left forearm for a month, with no significant past med- ical history or any history of trauma. -

Heart Tumors in Domestic Animals

HEART TUMORS IN DOMESTIC ANIMALS Marko Hohšteter Department of veterinary pathology, Veterinary Faculty University of Zagreb Neoplasms of the heart are rare diseases in domestic animals. Among all domestic animals heart neoplasm are most common in dogs. Most of the canine heart tumors are primary what is contrary to other domestic animals, in which most of cardiac tumors are metastatic. Primary tumors of the heart represent 0,69% of the canine tumors. Among all primary neoplasms canine hemangiosarcoma of the right atrium is the most common. Other primary cardiac tumors in domestic animals include rhabdomyoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, myxoma, myxosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, granular cell tumor, fibroma, fibrosarcoma, lipoma, pericardial mesothelioma and undifferentiated sarcoma. Aortic and carotid body tumors are usually classified under primary heart neoplasm but are actually tumors which arise in adventitia or periarterial adipose tissue of the aorta, carotid artery or pulmonary artery, and can extend to heart base. Hemangiosarcoma is the most important and most frequent cardiac neoplasm of dogs. This tumor develops primary from the blood vessels that line the heart or can matastasize from sites such as spleen, skin or liver. It is most commonly reported in mid to large breeds, such as boxers, German shepherds, golden retrievers, and in older dogs (six years and older). Aortic and carotide body adenoma and adenocarcinoma belong into the group of chemoreceptor tumors („chemodectomas“) and are morphologicaly similar. In animals, incidence of aortic body neoplasm is higher than that of the carotide body. Both tumors mostly develop in dogs (brachyocephalic breed: boxers, Boston teriers), and are rare in cats and cattle. -

Primary Mixed Myosarcoma of the Uterine Tube: a Case Report and Review of the Literature ALEXANDER S

Med. J. 258 CASE REPORT: MYOSAIRCOMAMYOSARCOMA OFUTERINEOF UTERINE TUBE Canad.Feb. 3, 1968, Ass.vol. 98 dans 1'cesophage superieur. Le plus petit malade REFERENCES chez qui une biopsie fut prelevee pesait 13 livres 1. CROSBY, W. H.: Amer. or. Dig. Dis., 8: 2, 1963. 2. CAREY, J. B., JR.: Gastroenterology, 46: 550, 1964. et 6tait age de 9 mois. 3. BECK, L T. et al.: Bull. Gastroint. EBndosc., 11: 15, 1965. We wish to thank 0. H. Kimbell, Ph.D., H. Robidoux- 4. MCDONALD, W. G.: Gastroenterology, 51: 390, 1966. 5. PARTIN, J. C. AND SCHUBERT, W. K: New Eng. J. Poirier, R.N., R.-M. Leblanc, R.N., D. Michaud, R.N., Med., 274: 94, 1966. and Marc Gigu6re, R.B.P., for their co-operation and 6. KUITUNEN, P. AND VISAKORPI, J. K.: Lancet, 1: 1276, active assistance. 1965. Primary Mixed Myosarcoma of the Uterine Tube: A Case Report and Review of the Literature ALEXANDER S. ULLMANN, M.D. and MAERIT B. KALLET, M.D., Detroit, Mich., U.S.A. SINCE primary malignant neoplasms of the uterine tube are so rare that no one indi- vidual or clinic has been able to study a large series of patients, the importance of reporting every case has often been emphasized.2-4 Although over 800 cases of primary carcinoma of the tube have been described in the liter- ature,4 up to 1956 only 30 authentic cases of primary sarcoma had been reported and to this number Abrams added another one.1' 8 Recently we had the opportunity to study a patient with primary sarcoma of the fallopian tube. -

Uterine Carcinosarcoma Associated with Pelvic Radiotherapy for Sacral Chordoma: a Case Report

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 51 (2012) 89e92 www.tjog-online.com Case Report Uterine carcinosarcoma associated with pelvic radiotherapy for sacral chordoma: A case report Korhan Kahraman a,*, Fırat Ortac a, Duygu Kankaya b, Gulsah Aynaoglu a a Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey b Department of Pathology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Accepted 28 December 2010 Abstract Objective: Postirradiation sarcoma of the female genital tract is rare, but a recognized event. Most reported cases have been associated with history of radiotherapy for various gynecologic conditions, particularly cancer of the uterine cervix and abnormal uterine bleeding. The occurrence of uterine sarcoma secondary to radiotherapy for a non-gynecologic tumor and, furthermore, this condition being simultaneous with the recurrence of primary tumor is unique. Case Report: A 67-year-old woman presented with a uterine mass which was diagnosed as a sarcoma by endometrial curettage and history of pelvic radiotherapy 23 years previously for sacral chordoma. Surgical staging procedure for uterine malignancy was performed. The final pathologic diagnosis was carcinosarcoma of the uterus. Conclusion: In uterine masses seen in patients with history of irradiation to the pelvic field, the probability of uterine sarcomas should always be kept in mind. These tumors may occur simultaneously with recurrence of primary tumor previously treated by adjuvant radiation therapy. Copyright Ó 2012, Taiwan Association of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Published by Elsevier Taiwan LLC. -

Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry for Canine Cutaneous Round Cell Tumours — Retrospective Analysis of 60 Cases

FOLIA HISTOCHEMICA ORIGINAL PAPER ET CYTOBIOLOGICA Vol. 57, No. 3, 2019 pp. 146–154 Diagnostic immunohistochemistry for canine cutaneous round cell tumours — retrospective analysis of 60 cases Katarzyna Pazdzior-Czapula, Mateusz Mikiewicz, Michal Gesek, Cezary Zwolinski, Iwona Otrocka-Domagala Department of Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Olsztyn, Poland Abstract Introduction. Canine cutaneous round cell tumours (CCRCTs) include various benign and malignant neoplastic processes. Due to their similar morphology, the diagnosis of CCRCTs based on histopathological examination alone can be challenging, often necessitating ancillary immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. This study presents a retrospective analysis of CCRCTs. Materials and methods. This study includes 60 cases of CCRCTs, including 55 solitary and 5 multiple tumours, evaluated immunohistochemically using a basic antibody panel (MHCII, CD18, Iba1, CD3, CD79a, CD20 and mast cell tryptase) and, when appropriate, extended antibody panel (vimentin, desmin, a-SMA, S-100, melan-A and pan-keratin). Additionally, histochemical stainings (May-Grünwald-Giemsa and methyl green pyronine) were performed. Results. IHC analysis using a basic antibody panel revealed 27 cases of histiocytoma, one case of histiocytic sarcoma, 18 cases of cutaneous lymphoma of either T-cell (CD3+) or B-cell (CD79a+) origin, 5 cases of plas- macytoma, and 4 cases of mast cell tumours. The extended antibody panel revealed 2 cases of alveolar rhabdo- myosarcoma, 2 cases of amelanotic melanoma, and one case of glomus tumour. Conclusions. Both canine cutaneous histiocytoma and cutaneous lymphoma should be considered at the beginning of differential diagnosis for CCRCTs. While most poorly differentiated CCRCTs can be diagnosed immunohis- tochemically using 1–4 basic antibodies, some require a broad antibody panel, including mesenchymal, epithelial, myogenic, and melanocytic markers. -

PROPOSED REGULATION of the STATE BOARD of HEALTH LCB File No. R057-16

PROPOSED REGULATION OF THE STATE BOARD OF HEALTH LCB File No. R057-16 Section 1. Chapter 457 of NAC is hereby amended by adding thereto the following provision: 1. The Division may impose an administrative penalty of $5,000 against any person or organization who is responsible for reporting information on cancer who violates the provisions of NRS 457. 230 and 457.250. 2. The Division shall give notice in the manner set forth in NAC 439.345 before imposing any administrative penalty 3. Any person or organization upon whom the Division imposes an administrative penalty pursuant to this section may appeal the action pursuant to the procedures set forth in NAC 439.300 to 439. 395, inclusive. Section 2. NAC 457.010 is here by amended to read as follows: As used in NAC 457.010 to 457.150, inclusive, unless the context otherwise requires: 1. “Cancer” has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 457.020. 2. “Division” means the Division of Public and Behavioral Health of the Department of Health and Human Services. 3. “Health care facility” has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 457.020. 4. “[Malignant neoplasm” means a virulent or potentially virulent tumor, regardless of the tissue of origin. [4] “Medical laboratory” has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 652.060. 5. “Neoplasm” means a virulent or potentially virulent tumor, regardless of the tissue of origin. 6. “[Physician] Provider of health care” means a [physician] provider of health care licensed pursuant to chapter [630 or 633] 629.031 of NRS. 7. “Registry” means the office in which the Chief Medical Officer conducts the program for reporting information on cancer and maintains records containing that information. -

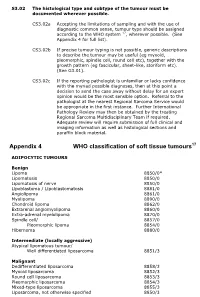

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

Misdiagnosed Infantile Rhabdomyofibrosarcoma: a Case Report

2766 ONCOLOGY LETTERS 12: 2766-2768, 2016 Misdiagnosed infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma: A case report TAO PAN1*, KEN CHEN1*, RUN-SONG JIANG2 and ZHENG‑YAN ZHAO2 Departments of 1General Surgery and 2Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310003, P.R. China Received January 19, 2015; Accepted February 16, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2016.5032 Abstract. Infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma is a rare form of infantile fibrosarcoma has uniform, solidly‑packed spindle cells soft‑tissue tumor often associated with difficulties in diagnosis. arranged in a fascicular or herringbone pattern similar to the The disease is positioned intermediately between rhabdo- vascular pattern observed with hemangiopericytoma (4). Infan- myosarcoma and infantile fibrosarcoma in terms of clinical tile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma may be identified as childhood presentation, immunohistochemistry, behavior, morphology spindle‑cell sarcoma with a low degree of rhabdoid differentiation and ultrastructural features. Reports of rhabdomyofibrosarcoma and aggressive clinical behavior (5). Overlooking the diagnosis cases are limited in the literature. The present case describes a of infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma may increase the chances 26‑month‑old female who presented with a slowly progressive, of local recurrence or metastatic disease; therefore, aggressive soft‑tissue mass in the right chest wall. The mass was success- multimodality treatment is required for these patients (6). Reports fully treated with surgery. Using histopathology, the tumor was of rhabdomyofibrosarcoma cases are limited in the literature. diagnosed and classified as infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma. The present case report describes a 26‑month‑old patient who The patient has been followed‑up for 2 years and is currently presented with a slowly progressive, soft‑tissue mass in the right in good condition. -

Partners in Care – January 2017

The newSEE CE Schedule INSIDE & on a Referralremovable Contact postcard! Info Partners In Care Veterinary Referral News from Angell Animal Medical Center Winter 2017 π Volume 11:1 π angell.org π facebook.com/AngellReferringVeterinarians PRE-HOSPITAL EYELID MARGIN SEDATION OPTIONS BUILDING A RADIOGRAPHIC TUMOR GRADING— MASSES IN DOGS: FOR AGGRESSIVE AND CONFIDENT PUPPY APPROACH TO IS IT APPLICABLE? TO CUT OR ANXIOUS DOGS BONE IMAGING NOT TO CUT? PAGE 1 PAGE 1 PAGE 4 PAGE 6 PAGE 8 ANESTHESIA BEHAVIOR Pre-Hospital Sedation Building a Options for Aggressive Confident Puppy and Anxious Dogs π Terri Bright, Ph.D., BCBA-D, CAAB π Kate Cummings, DVM, DACVAA angell.org/behavior [email protected] angell.org/anesthesia 617-989-1520 [email protected] 617-541-5048 ggressive and/or fearful dogs present several challenges for the othing makes everyone happier than having puppies in the small animal practitioner. These patients are difficult to fully veterinary office. The client brings the pup soon after they evaluate and present a safety hazard to the clinic staff, purchase or adopt it to make sure it is healthy, and to begin the veterinarian, and sometimes even the owner. In addition, a process of vaccinations and a lifetime of health. Everyone oohs Anervous dog contributes to heightened stress within the work area affecting Nand ahs over it, but what are the most important things a vet and their staff not only people, but other pets alike. In dogs known to be aggressive within can do to make sure the pup grows up to be happy and behaviorally healthy? the hospital setting or those with tremendous fear/anxiety, making physical exams and basic assessment impossible, pre-hospital sedation can First, find out what the puppy’s history is. -

Evidenzbericht: S3-Leitlinie „Adulte Weichgewebesarkome“

Institut für Forschung in der Operativen Medizin (IFOM) Evidenzbericht: S3-Leitlinie „Adulte Weichgewebesarkome“ IFOM - Institut für Forschung in der Operativen Medizin (Universität Witten/Herdecke) Jessica Breuing, Tim Mathes, Katharina Doni, Tanja Rombey, Barbara Prediger, Dawid Pieper Datum: 03.07.2020 Kontakt: Jessica Breuing IFOM - Institut für Forschung in der Operativen Medizin Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rolf Lefering Fakultät für Gesundheit, Department für Humanmedizin Universität Witten/Herdecke Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38 51109 Köln Tel.: 0221 98957-41 Fax: 0221 98957-30 Dr. Tim Mathes IFOM - Institut für Forschung in der Operativen Medizin Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rolf Lefering Fakultät für Gesundheit, Department für Humanmedizin Universität Witten/Herdecke Ostmerheimer Str. 200, Haus 38 51109 Köln Tel.: 0221 98957-43 Fax: 0221 98957-30 Inhalt 1. Literaturrecherche ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1. Einschlusskriterien Systemtherapie ....................................................................................... 5 1.1.1. Neoadjuvante Systemtherapie (+ GIST) ........................................................................ 5 1.1.2. Adjuvante Systemtherapie (+ GIST) ............................................................................... 5 1.1.3. Therapie der metastasierten Erkrankung (+ GIST) ...................................................... 6 1.2. Einschlusskriterien Chirurgie .................................................................................................. -

Desmoplastic Fibroma

Send Orders of Reprints at [email protected] 40 The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 2013, 7, 40-46 Open Access Desmoplastic Fibroma: A Case Report with Three Years of Clinical and Radiographic Observation and Review of the Literature Alexander Nedopil*, Peter Raab and Maximilian Rudert Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Würzburg, König Ludwig Haus, Germany Abstract: Background: Desmoplastic fibroma (DF) is an extremely rare locally aggressive bone tumor with an incidence of 0.11% of all primary bone tumors. The typical clinical presentation is pain and swelling above the affected area. The most common sites of involvement are the mandible and the metaphysis of long bones. Histologically and biologically, desmoplastic fibroma mimics extra-abdominal desmoid tumor of soft tissue. Case Presentation and Literature Review: A case of a 27-year old man with DF in the ilium, including the clinical, radiological and histological findings over a 4-year period is presented here. CT scans performed in 3-year intervals prior to surgical intervention were compared with respect to tumor extension and cortical breakthrough. The patient was treated with curettage and grafting based on anatomical considerations. Follow-up CT scans over 18-months are also documented here. Additionally, a review and analysis of 271 cases including the presented case with particular emphasis on imaging patterns in MRI and CT as well as treatment modalities and outcomes are presented. Conclusion: In patients with desmoplastic fibroma, CT is the preferred imaging technique for both the diagnosis of intraosseus tumor extension and assessment of cortical involvement, whereas MRI is favored for the assessment of extraosseus tumor growth and preoperative planning. -

The New EU Agenda on Cancer and the Role of the European Reference Network EURACAN Jean Yves Blay

14 1 2021 The new EU Agenda on Cancer and the role of the European Reference Network EURACAN J-Y Blay Rare Adult Solid Cancers Co-funded by the EU Connective tissue Female genital organs and placenta Male genital organs, and of the urinary tract Neuroendocrine system Digestive tract Endocrine organs Head and neck Thorax Skin and eye melanoma Brain, spinal cords Geographical spreading of the Consortium all over Europe. 2017 66 full members accross 17 Member states Cyprus 2020 9 APS accross 7 Member States 2021 42 new members EURACAN - Lyon_Centre Léon Bérard November 2020 ASSOCIATE PARTNERS EURACAN - Lyon_Centre Léon Bérard November 2020 AFFILIATED PARTNERS Associated National Centres approved National Coordination hub approved Austria • Centre for bone and soft tissue tumors – Graz Luxembourg -Hospital Centre Croatia Malta - Mater dei Hospital - • University Hospital centre - Zagreb • Sestre University Hospital centre - Zagreb Cyprus • Bank of Cyprus oncology centre in collaboration with the Karaiskakio Foundation Estonia • North Estonia Medical Centre • University Hospital - Taru Latvia • East clinical University Hospital - Riga Member state Town Candidate Name DOMAIN(S) APPROVED BY THE BoN code G1.1 G2.2 G5.2 G9.1 G10 Brussels Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc ASBL BE G1 G2.2 G3.1 G6.1 G9.2 Ghent Ghent University Hospital Prague Thomayer Hospital G3.1 CZ G2.1 Prague The institute for the Care of Mother and Child Berlin Helios Klinikum Berlin-Buch G1.1 G1.2 DE G1.1 G1.2 G2.1 G2.2 G3.1 G4 G5.1 G5.2 Munich Comprehensive Cancer Center