Ethnological Expertise in Yakutia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express Via the BAM and Yakutsk

Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express via the BAM and Yakutsk https://www.irtsociety.com/journey/golden-eagle-trans-siberian-express-bam-line/ Overview The Highlights - Explore smaller and remote towns of Russia, rarely visited by tourists - Grand Moscow’s Red Square, the Kremlin Armoury Chamber, St. Basil's Cathedral and Cafe Pushkin - Yekaterinburg, infamous execution site of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, their son, daughters and servants, by the Bolsheviks in 1918 - Fantastic Sayan Mountain scenery, including the Dzheb double horse-shoe curves The Society of International Railway Travelers | irtsociety.com | (800) 478-4881 Page 1/7 - Visit one of the biggest hydro-electric dams in the world in Bratsk and one of the world’s largest open cast mines in Neryungri - Stop at the unique and mysterious 3.7-mile (6km) long Chara Sand Dunes - Learn about the history and building of the BAM line at the local museum in Tynda - Marvel at Komsomolsk's majestic and expansive urban architecture of the Soviet era, including the stupendous Pervostroitelei Avenue, lined with Soviet store fronts and signage intact - City tour of Vladivostok, including a preserved World War II submarine - All meals, fine wine with lunch and dinner, hotels, gratuities, off-train tours and arrival/departure transfers included The Tour Travel by private train through an outstanding area of untouched natural beauty of Siberia, along the Baikal-Amur Magistral (BAM) line, visiting some of the lesser known places and communities of remote Russia. The luxurious Golden Eagle will transport you from Moscow to Vladivostok along the less-traveled, northerly Trans-Siberian BAM line. -

Chapter 7. Cities of the Russian North in the Context of Climate Change

? chapter seven Cities of the Russian North in the Context of Climate Change Oleg Anisimov and Vasily Kokorev Introduction In addressing Arctic urban sustainability, one has to deal with the com- plex interplay of multiple factors, such as governance and economic development, demography and migration, environmental changes and land use, changes in the ecosystems and their services, and climate change.1 While climate change can be seen as a factor that exacerbates existing vulnerabilities to other stressors, changes in temperatures, precipitation, snow accumulation, river and lake ice, and hydrological conditions also have direct implications for Northern cities. Climate change leads to a reduction in the demand for heating energy, on one hand, and heightens concerns about the fate of the infrastruc- ture built upon thawing permafrost, on the other. Changes in snowfall are particularly important and have direct implications for the urban economy, because, together with heating costs, expenses for snow removal from streets, airport runways, roofs, and ventilation spaces underneath buildings standing on pile foundations built upon perma- frost constitute the bulk of a city’s maintenance budget during the long cold period of the year. Many cities are located in river valleys and are prone to fl oods that lead to enormous economic losses, inju- ries, and in some cases human deaths. The severity of the northern climate has a direct impact on the regional migration of labor. Climate could thus potentially be viewed as an inexhaustible public resource that creates opportunities for sustainable urban development (Simp- 142 | Oleg Anisimov and Vasily Kokorev son 2009). Long-term trends show that climate as a resource is, in fact, becoming more readily available in the Russian North, notwith- standing the general perception that globally climate change is one of the greatest challenges facing humanity in the twenty-fi rst century. -

Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Is the Largest Region in the Russian Federation and One of the Richest in Natural Resources

Investor's Guide to the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is the largest region in the Russian Federation and one of the richest in natural resources. Needless to say, the stable and dynamic development of Yakutia is of key importance to both the Far Eastern Federal District and all of Russia…” President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin “One of the fundamental priorities of the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is to develop comfortable conditions for business and investment activities to ensure dynamic economic growth” Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Egor Borisov 2 Contents Welcome from Egor Borisov, Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 5 Overview of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 6 Interesting facts about the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 7 Strategic priorities of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) investment policy 8 Seven reasons to start a business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 10 1. Rich reserves of natural resources 10 2. Significant business development potential for the extraction and processing of mineral and fossil resources 12 3. Unique geographical location 15 4. Stable credit rating 16 5. Convenient conditions for investment activity 18 6. Developed infrastructure for the support of small and medium-sized enterprises 19 7. High level of social and economic development 20 Investment infrastructure 22 Interaction with large businesses 24 Interaction with small and medium-sized enterprises 25 Other organisations and institutions 26 Practical information on doing business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 27 Public-Private Partnership 29 Information for small and medium-sized enterprises 31 Appendix 1. -

The Mineral Indutry of Russia in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF RUSSIA By Richard M. Levine Russia extends over more than 75% of the territory of the According to the Minister of Natural Resources, Russia will former Soviet Union (FSU) and accordingly possesses a large not begin to replenish diminishing reserves until the period from percentage of the FSU’s mineral resources. Russia was a major 2003 to 2005, at the earliest. Although some positive trends mineral producer, accounting for a large percentage of the were appearing during the 1996-97 period, the financial crisis in FSU’s production of a range of mineral products, including 1998 set the geological sector back several years as the minimal aluminum, bauxite, cobalt, coal, diamonds, mica, natural gas, funding that had been available for exploration decreased nickel, oil, platinum-group metals, tin, and a host of other further. In 1998, 74% of all geologic prospecting was for oil metals, industrial minerals, and mineral fuels. Still, Russia was and gas (Interfax Mining and Metals Report, 1999n; Novikov significantly import-dependent on a number of mineral products, and Yastrzhembskiy, 1999). including alumina, bauxite, chromite, manganese, and titanium Lack of funding caused a deterioration of capital stock at and zirconium ores. The most significant regions of the country mining enterprises. At the majority of mining enterprises, there for metal mining were East Siberia (cobalt, copper, lead, nickel, was a sharp decrease in production indicators. As a result, in the columbium, platinum-group metals, tungsten, and zinc), the last 7 years more than 20 million metric tons (Mt) of capacity Kola Peninsula (cobalt, copper, nickel, columbium, rare-earth has been decommissioned at iron ore mining enterprises. -

State of Uncertainty Educating the First Railroaders in Central Sakha (Yakutiya)

State of Uncertainty Educating the First Railroaders in Central Sakha (Yakutiya) Sigrid Irene Wentzel Abstract In July 2019, the village of Nizhniy Bestyakh in the Republic of Sakha (Ya- kutiya), the Russian Far East, was fi nally able to celebrate the opening of an eagerly awaited railroad passenger connection. Th rough analysis of rich eth- nographic data, this article explores the “state of uncertainty” caused by re- peated delays in construction of the railroad prior to this and focuses on the eff ect of these delays on students of a local transportation college. Th is college prepares young people for railroad jobs and careers, promising a steady in- come and a place in the Republic’s wider modernization project. Th e research also reveals how the state of uncertainty led to unforeseen consequences, such as the seeding of doubt among students about their desire to be a part of the Republic’s industrialization drive. Keywords economic development, education, infrastructure supply, planning, railways, Russia, uncertainty, youth When I came to the village of Nizhniy Bestyakh in April 2015 to do fi eldwork, I happened to be the only guest at Anya’s guesthouse. “What are you doing here?” she asked. “I want to study the railroad development and its eff ects on the people,” I responded. Amused, yet skeptical, Anya replied, “I am afraid you won’t fi nd anything to study here, the railroad is not really working. Everybody prepared for the opening, the young got educated and now . nothing.”1 While the existence of railway connections may be taken for granted in some parts of the world, few places today off er the opportunity to observe the in- stallation of a new railway line. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Oil Pipeline Construction in Eastern Siberia: Implications for Indigenous People ⇑ Natalia Yakovleva

Geoforum 42 (2011) 708–719 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geoforum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geoforum Oil pipeline construction in Eastern Siberia: Implications for indigenous people ⇑ Natalia Yakovleva Winchester Business School, University of Winchester, Sparkford Road, Winchester, Hampshire SO22 4NR, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Traditional economic activities, lifestyles and customs of many indigenous peoples in the Russian North, Received 12 March 2010 such as reindeer herding, hunting and fishing, are closely linked to quality of the natural environment. Received in revised form 6 April 2011 These traditional activities that constitute the core of indigenous cultures are impacted by extractive sec- Available online 14 July 2011 tor activities conducted in and around traditional territories of indigenous peoples. This paper examines implications of an oil pipeline development in Eastern Siberia on the Evenki community in the Aldan dis- Keywords: trict of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). It examines community concerns about potential environmental Indigenous damage and impacts on traditional livelihood. The paper analyses the interaction of indigenous commu- Activism nities with the pipeline project through interrogation of elements such as impact assessment, consulta- Participation Extractive tion, compensation, benefits, communication and public activism. The paper discusses how state policy Yakutia and industry’s approach towards land rights and public participation affects the position of indigenous Pipeline peoples and discusses barriers for their effective engagement. The analysis shows a number of policy fail- ures in the protection of traditional natural resource use of indigenous peoples and provision of benefits with regards to the extractive sector that leave indigenous peoples marginalised in the process of devel- opment. -

Buildings Stability Revaluation in Seismically Active Regions

MATEC Web of Conferences 106, 02009 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201710602009 SPbWOSCE-2016 Buildings Stability Revaluation in Seismically Active Regions Natalia Koretskaya 1,*, and Nikolay Grib2 1Теchnical Institute (branch) of North-Eastern Federal university after М.К. Аммоsov, Neryungri, Russia 2Теchnical Institute (branch) of North-Eastern Federal university after М.К. Аммоsov, Neryungri, Russia Abstract. In 2015 the maps of seismic zoning on the territory of Russia were detailed according to new general standards (ОSR-2015). Compared to the previous data, the number of seismically dangerous areas has the tendency to increase. Most buildings in those areas of the country were designed and constructed as less earthquake resistant. The physical and mechanical characteristics of the soil in the buildings foundation are being changed under the influence of different ecological, engineering, geological, and man-made factors. The latest research discovers the high level of soil influence on seismic resistance of buildings. Further detailed examination of earthquake resistance of buildings in the northern territories of Russia has been planned according to the changes and influences mentioned above in order to lower the earthquake risks. Introduction The research of recent decades discovers the increasing risks of seismic disasters that can be connected with the human activities, different anthropogenic influences on the Earth's crust, geological, engineering, seismological, and environmental factors, as discussed in [1-3]. Latest Maps of General seismic zoning of the Russian Federation territory (GSZ-2015) have shown the following tendencies: the number of regions with high seismic risks has increased significantly compared to the previous data, as discussed in [4, 5]. -

Yakutia) December 13/2016 Acad

1 61 8 ЯКУТСКИЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ ЖУРНАЛ YAKUT MEDICAL SCIENTIFIC - PRACTICAL JOURNAL OF THE YAKUT SCIENCE CENTRE JOURNAL OF COMPLEX MEDICAL PROBLEMS ISSN 1813-1905 (print) ISSN 2312-1017 (online) 1(61) `2018 ЯКУТСКИЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ ЖУРНАЛ The founder The Yakut Science Centre of Complex Medical Problems YAKUT Editor- in- chief Romanova A.N., MD Editorial Board: MEDICAL Deputy Chief Editor and Executive secretary Nikolaev V.P., MD Scientifc editor JOURNAL Platonov F.A. MD Editorial Council: SCIENTIFIC - PRACTICAL JOURNAL Aftanas L.I., MD, Professor, OF THE YAKUT SCIENCE CENTRE OF COMPLEX acad. RAMS (Novosibirsk) MEDICAL PROBLEMS Voevoda M.I., MD, Professor, Corresponding Member RAMS (Novosibirsk) Ivanov P.M., MD, Professor (Yakutsk) Kryubezi Eric, MD, Professor (France) Quarterly Maksimova N.R., MD (Yakutsk) Mironova G.E., Doctor of Biology, Registered by the Offce of the Federal Service on Professor (Yakutsk) supervision in the feld of communications, information Mikhailova E.I., Doctor of Pedagogics, Professor (Yakutsk) technologies and mass communications in the Republic Nikitin Yu.P., MD, Professor, Sakha (Yakutia) December 13/2016 Acad. RAMS (Novosibirsk) Odland John, MD, Professor (Norway) Registration number PI No.ТU 14-00475 Puzyrev V.P., MD, Professor, Acad. RAMS (Tomsk) Subscription index: 78781 Reutio Arya, MD, PhD, Professor (Finland) Fedorova S.A., Doctor of Biology (Yakutsk) Free price Husebek Anne, MD, Professor (Norway) Khusnutdinova E.K., Doctor of Biology, Professor (Ufa) «Yakut Medical Journal» is included in the approved by Editors: the Higher Attestation Commission of the Russian Chuvashova I.I., Federation List of leading peer-reviewed scientifc Kononova S.l. journals and publications, in which the main scientifc Semenova T.F. -

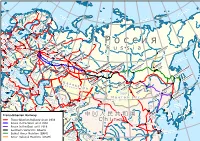

Trans-Siberian Railway

Narvik East Siberian Sea Barents Sea Norge Мурманск Norway Murmansk Oslo Sverige Kara Sea Sweden Laptev Sea North Sea Stockholm Danmark Helsinki Denmark Suomi Baltic Finland København Sea Copenhagen Архангельск Arkhangelsk DeutschlandBerlin Germany Tallinn Калининград Kaliningrad Санкт- Лабытнанги Петербург Labytnangi Praha Rīga Saint Prague Warszawa Petersburg Warsaw Обь Новый Уренгой Vilnius Novy Urengoy Polska Ob Česko Czech Republic Poland Россия Wien Vienna Ярославль Yaroslavl Приобье БеларусьМінск Priobye BelarusMinsk Russia Bratislava Кама Кама Kama Киров Kama Kirov Magyarország Нижний Новгород Енисей Нижний Бестях Hungary Budapest Nizhny Novgorod Yenisei Nizhny Bestyakh Волга Київ Алдан Kiev Volga Казань Пермь Aldan Днепр Москва România Dnieper MoscowТула Kazan Perm Tula Србија Србија Romania Serbia Serbia Београд Belgrade Екатеринбург Рязань YekaterinburgТюмень Sea of Okhotsk Україна Ryazan Tyumen Иртыш Irtysh Prishtina ChișinăuUkraine Лена Kishinev Lena București Нерюнгри България Bucharest Дон Bulgaria Don Neryungri София Тайга Тында Sofia Тобол Омск Tynda УфаUfa Omsk Taiga Северобайкальск Tobol КрасноярскТайшетTayshet НовосибирскNovosibirsk Krasnoyarsk Severobaikalsk Ростов- СамараSamara Ural Урал Томь Black Sea Tom Angara на-Дону Ангара Volga Обь İstanbul Rostov- Ob Istanbul on-Don Челябинск Комсомольск-на-Амуре Chelyabinsk Нұр-Сұлтан Komsomolsk-on-Amur Сочи Nur-Sultan Sochi Байкал Ankara Lake Baikal Советская Гавань Sovetskaya Gavan Georgia Барнаул Caspian Қазақстан Türkiye Barnaul Аргунь Абакан Амур Turkey Kazakhstan Abakan -

Yakut Medical Journal

ISSN 1813-1905 (print) ISSN 2312-1017 (online) 3(63) `2018 ЯКУТСКИЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ ЖУРНАЛ The founder The Yakut Science Centre of Complex Medical Problems YAKUT Editor- in- chief Romanova A.N., MD Editorial Board: MEDICAL Deputy Chief Editor and Executive secretary Nikolaev V.P., MD Scientific editor Platonov F.A. MD JOURNAL Editorial Council: SCIENTIFIC - PRACTICAL JOURNAL Aftanas L.I., MD, Professor, OF THE YAKUT SCIENCE CENTRE OF COMPLEX acad. RAMS (Novosibirsk) MEDICAL PROBLEMS Voevoda M.I., MD, Professor, Corresponding Member RAMS (Novosibirsk) Ivanov P.M., MD, Professor (Yakutsk) Kryubezi Eric, MD, Professor (France) Quarterly Maksimova N.R., MD (Yakutsk) Mironova G.E., Doctor of Biology, Registered by the Office of the Federal Service on Professor (Yakutsk) supervision in the field of communications, information Mikhailova E.I., Doctor of Pedagogics, Professor (Yakutsk) technologies and mass communications in the Republic Nikitin Yu.P., MD, Professor, Sakha (Yakutia) December 13/2016 Acad. RAMS (Novosibirsk) Odland John, MD, Professor (Norway) Registration number PI No.ТU 14-00475 Puzyrev V.P., MD, Professor, Acad. RAMS (Tomsk) Subscription index: 78781 Reutio Arya, MD, PhD, Professor (Finland) Fedorova S.A., Doctor of Biology (Yakutsk) Free price Husebek Anne, MD, Professor (Norway) Khusnutdinova E.K., Doctor of Biology, Professor (Ufa) «Yakut Medical Journal» is included in the approved by Editors: the Higher Attestation Commission of the Russian Chuvashova I.I., Federation List of leading peer-reviewed scientific Kononova S.l. journals and publications, in which the main scientific Semenova T.F. (English) results of dissertations for the acquisition of scientific degrees of Doctor and Candidate of science on Computer design biological sciences and medicine should be published. -

VI. Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Overview of the Region Josh

Saving Russia's Far Eastern Taiga : Deforestation, Protected Areas, and Forests 'Hotspots' VI. Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Overview of the Region Josh Newell Location The Republic of Yakutia (Sakha), situated in northeastern Siberia, stretches to the Henrietta Islands (77 N) in the far north and is washed by the Arctic Ocean (Laptev and Eastern Siberian Seas). These waters, the coldest and iciest of all seas in the northern hemisphere, are covered by ice for 9 to 10 months of the year. The Stanovoy Ridge (55 D. 30 D. N) borders Yakutia in the south, the upper reaches of the Olenyok River form the western border, and Chukotka forms the eastern border (165 E). Size Almost one-fifth of the territory of the Russian Federation (3,103,200 sq. km.) and greater than the combined areas of France, Austria, Germany, Italy, Sweden, England, Greece, and Finland. Climate Winter is prolonged and severe, with average January temperatures about -40C. Summer is short but warm; the average in July is 13C and temperatures have reached 39C in Yakutsk. In the northeast, the town of Verekhoyansk reaches -70C (-83F) and is considered the coldest inhabited place on Earth. There is little precipitation - from 150-200 mm. in Central Yakutia to 500-700 mm. in the mountains of eastern and southern Yakutia. Geography and Ecology Forty percent of Yakutia lies within the Arctic Circle and all of it is covered by eternally frozen ground- permafrost - which greatly influences the region's ecology and limits forests to the southern region. Yakutia can be divided into three great vegetation belts.